The London School of Economics and Political Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2020/21 for the Year Ended 31 January 2021 Addressing Challenges with Resilience And

SIMONDS FARSONS CISK PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 JANUARY 2021 ADDRESSING CHALLENGES WITH RESILIENCE AND ADAPTABILITY THE OLD BREWHOUSE PROJECT, FEATURED ON THE FRONT COVER, IS NEARING COMPLETION, AND MARKS THE FIRST LOCAL CONVERSION OF SUCH A LARGE-SCALE AND LISTED INDUSTRIAL SPACE. IN MANY WAYS, THE CAREFUL RESTORATION AND TRANSFORMATION OF THIS ICONIC ASSET EMBODIES HOW THE FARSONS GROUP IS ADDRESSING CHALLENGES WITH RESILIENCE AND ADAPTABILITY, AS IT GIVES A NEW LEASE OF LIFE AND PURPOSE TO AN INTRINSIC PART OF MALTA’S BREWING HERITAGE. SIMONDS FARSONS CISK PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 ANNUAL REPORT 2020/21 1 Simonds Farsons Cisk plc CONTENTS Annual Report for the year ended 31 January 2021 02. Chairman’s Statement 60. Independent Auditor’s Report 04. Board of Directors 66. Statements of Financial Position 05. Board Committees 68. Income Statements 05. The Farsons Foundation 69. Statements of Comprehensive 05. Senior Management Board Income 06. The Regeneration of an Icon 70. Statements of Changes in Equity 08. Group Chief Executive’s Review 72. Statements of Cash Flows 37. Financial Statements 73. Notes to the Consolidated Financial 38. Directors’ Report Statements 43. Statement by the Directors on 104. Shareholder Information Non-Financial Information 105. Five Year Summarised Group 49. Corporate Governance Statement Results 56. Remuneration Report SIMONDS FARSONS CISK PLC 2 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT The forthcoming 74th Annual General Meeting of Simonds 29.4% during the year under review. The drop in Turnover was Farsons Cisk plc will be the 48th that I would have attended experienced across all sectors, with the higher drops being in person, of which 45 I have attended as a board member. -

Non-Alcoholic Beverages

Alcoholic Beverages Non-Alcoholic Beverages WINE SPIRITS Britvic Ginger Ale The spicy yet fresh sparkling ginger taste of the Britvic Ginger Ale suits the personality of our whiskies perfectly but can also be enjoyed on its own Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot of Malta │ Melqart Blended Scotch Whisky │ Johnnie Walker Gold Label over ice. An artful blend of Cabernet Sauvignon & Merlot grapes resulted in the creation Blending multiple single malt whiskeys structured around a core of single malt of Meridiana Wine Estate’s Melqart. With an aroma reminiscent of ripe berry whisky from Clynelish, the luxuriously smooth Johnnie Walker Gold Label Britvic Bitter Lemon fruits with spiced notes, the ruby-red wine boasts a rich, blackberry flavour whisky contains rich, exotic flavours which combine to create one The zesty character of Britvic bitter lemon would perfectly complement the with silky tannins and a smooth, long finish. sensationally long, lingering toffee-tinged finish. clean, smooth base of Grey Goose vodka. Chardonnay of Malta DOK │ Isis Cognac │ Rémy Martin VSOP Britvic Tonic Water Meridiana Wine Estate's flagship wine, Isis, is a medium-bodied Chardonnay. The perfect harmony of powerful and elegant aromas, the smooth yet fruity To create a classic gin and tonic cocktail, we suggest pairing the Britvic tonic Isis reveals a complex nose of exotic fruits complemented by gentle floral VSOP Cognac from Rémy Martin is characterised by a mixture of aromas of water with our Hendrick’s Gin. notes, while its well-structured, citrus taste is followed by a pleasantly vanilla, toasted oak, apricot, baked apple and white flowers, with a palate acidic aftertaste. -

C&S Menu 2019

BRUNCH Croissants 2.50 Selection of freshly baked croissants Ham & Cheese Toastie 3.60 Smoked ham and melted cheese in toasted sliced bread Yoghurt & Granola Parfait 5.50 Fresh yoghurt, granola mix, seasonal fruit and chocolate syrup House Omelette 5.90 Three egg omlete with cheese and petite salad (add €1 per extra ingredient) Smoked Salmon Panini 7.80 Smoked salmon, cucumber and yoghurt in brown multi-seed panini Classic Club Sandwich 8.50 Chicken, bacon, egg, lettuce, tomato and house mayo served with crisps SALADS Freshly made salads to order with our in-house dressings, including basil lemon vinaigrette, honey mustard vinaigrette and the classic Ceasar dressing. Greek Salad 7.90 Feta cheese, olives, red onions, cucumber, bell peppers and tomatoe wedges Tuna Salad 7.90 Tuna chunks, egg wedges, olives, red onions, cherry tomatoes and mixed leaves Caprese 8.20 Mozzarella di Bufala, freshly sliced tomatoes and basil on a bed of rucola Chicken Ceasar 8.50 Chicken, bacon, parmiggiano shavings, cherry tomatoes, croutons and mixed leaves Brie & Bacon 8.80 Brie cheese and bacon bits with prunes, walnuts and mixed leaves Tuscan 8.80 Parma ham, mozzarella di Bufala, tomatoes, onions and mixed leaves Smoked Salmon 9.80 Smoked salmon, cherry tomatoes, cucumber, red onions and mixed leaves BAR BITES Cheesy Garlic Bread 3.80 Melted cheese and garlic butter on a warm ciabatta base Bruschetta 3.60 Fresh tomatoes, basil, red onions and olive oil on ciabatta slices Grilled Halloumi 6.50 Grilled halloumi cheese and rucola on toasted ciabatta slices Maltese -

Ice Creams Beer Wine by the Glass Beverages Cocktails

ICE CREAMS BEER WINE BY THE BOSS Range €3.25 CAN GLASS Extreme Triple Chocolate €3.00 Cisk (33cl) €2.85 WHITE WINE Lion €3.00 Cisk Excel (33cl) €2.95 Cape Heights Chenin Blanc €3.00 KitKat €3.00 Cisk Chill (25cl) €2.50 Victoria Heights Chardonnay €3.50 Hello Kitty (GF) €3.00 Hopleaf (33cl) €2.95 ROSE WINE Pirulo Range €2.65 BOTTLE Cape Heights Rose €3.00 Ice Lolly Orange/Cola €2.65 Cisk (25cl) €2.25 Victoria Heights Shiraz Rose €3.50 Smarties Push Up €2.65 Cisk Excel (25cl) €2.35 RED WINE Blue Label (33cl) €3.85 BEVERAGES Cape Heights Cab Sauv €3.00 Heineken (25cl) €2.35 Coca Cola (33cl) €1.90 (50cl) €3.25 Victoria Heights Merlot €3.50 Corona (33cl) €3.50 Coca Cola Zero (33cl) €1.90 (50cl) €3.25 Homemade Sangria €3.50 Budwuiser (25cl) €2.35 Fanta (33cl) €1.90 (50cl) €3.25 Maeloc Way (25cl) €4.50 WINE BY THE Kinnie (33cl) €1.90 (50cl) €3.25 Strawberry Fresca, Blackberry Mora, Pear, Kinnie Diet (33cl) €1.90 (50cl) €3.25 Seca Red Apple, Dulce Green Apple BOTTLE Organic Cider WHITE WINE Sprite (33cl) €1.90 (50cl) €3.25 Isis Chardonnay €34.95 Sprite Zero (33cl) €1.90 (50cl) €3.25 Laurenti Vermentino €35.00 Iced Tea (25cl) €1.90 (50cl) €3.25 COCKTAILS & Medina Sauvignon Blanc €15.95 Apple Juice, Orange Juice, Pineapple MOCKTAILS Juice (25cl) €2.00 Aperol Spritz €6.50 Cape Heights Chenin Blanc €13.95 Aperol, sparkling wine, soda water Cranberry Juice (25cl) €2.25 Pinot Grigio IGT Cesari Fiorile €17.95 Espresso Martini €7.00 Fresh Orange Juice (25cl) €3.00 Vodka, kahlua, espresso, sugar syrup Grillo Canapi DOC Sicilia €15.95 Crème de Café (25cl) -

Scotch Whisky, They Often Refer to A

Catalogue Family Overview Styles About the Font LL Catalogue is a contemporary a rising demand for novels and ‘news’, update of a 19th century serif font of these fonts emerged as symptom of Catalogue Light Scottish origin. Initially copied from a new culture of mass education and an old edition of Gulliver’s Travels by entertainment. designers M/M (Paris) in 2002, and In our digital age, the particularities Catalogue Light Italic first used for their redesign of French of such historical letterforms appear Vogue, it has since been redrawn both odd and unusually beautiful. To from scratch and expanded, following capture the original matrices, we had Catalogue Regular research into its origins and history. new hot metal types moulded, and The typeface originated from our resultant prints provided the basis Alexander Phemister’s 1858 de- for a digital redrawing that honoured Catalogue Italic sign for renowned foundry Miller & the imperfections and oddities of the Richard, with offices in Edinburgh and metal original. London. The technical possibilities We also added small caps, a Catalogue Bold and restrictions of the time deter- generous selection of special glyphs mined the conspicuously upright and, finally, a bold and a light cut to and bold verticals of the letters as the family, to make it more versatile. Catalogue Bold Italic well as their almost clunky serifs. Like its historical predecessors, LL The extremely straight and robust Catalogue is a jobbing font for large typeface allowed for an accelerated amounts of text. It is ideally suited for printing process, more economical uses between 8 and 16 pt, provid- production, and more efficient mass ing both excellent readability and a distribution in the age of Manchester distinctive character. -

Empire News Spring 2007 (PDF 4695Kb)

EmpireEmpire StateState CollegeCollege ALUMNIALUMNI ANDAND STUDENTSTUDENT NEWSNEWS VOLUMEVOLUME 3232 •• NUMBERNUMBER 22 •• SPRINGSPRING 20072007 Recipe for Learning 2006 Donors Report A Grateful Farewell to President Moore Empire State College ALUMNI AND STUDENT NEWS VOLUME 32 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2007 C o n t e n t s Joseph Moore President Kirk Starczewski Director of College Relations FEATURES Publisher [email protected] Upfront . 1 Maureen Winney Managing Editor From a Chef’s Perspective. 2 [email protected] Hope Ferguson Healthy Dining with Finesse . 3 Community Relations Associate Editor [email protected] Food is Hot in Arizona . 5 Gael Fischer Director of Publications/Designer Blending Haute Cuisine with Higher Education . 7 Debra Park Secretary, Office of College Relations Business Couldn’t Be Sweeter . 10 Alumni News and Copy Editor Evolution of a Pastry Chef. 11 CONTRIBUTORS Raymond Brownell Building an Industry with Heart and Determination. 13 Executive Director, Empire State College Foundation Working with a Snack and Beverage Giant . 14 Hugh Hammett Vice President for External Affairs Kim Neher Assistant Director of Alumni and Student Relations AROUND EMPIRE STATE COLLEGE Vicki Schaake Director of Advancement Services College News . 15 Alta Schallen Director of Gift Planning Faculty News . 16 Renelle Shampeny Director of Marketing Alumni News . 19 WRITERS Back to You . 21 Hope Ferguson Patricia Ingram ’04 Marie Morrison ’06 Deborah Smith m PHOTOGRAPHY Sum er is ! Cover: Chef Daniel Smith th by Liz Lajeunesse C ga Stock Studios o to Rik Walton m ara Join us for All other photos courtesy of our alumni, e to S students and staff Empire State College’s annual PRODUCTION Day at the Races Jerry Cronin Director of Management Service Ron Kosiba August 17, 2007. -

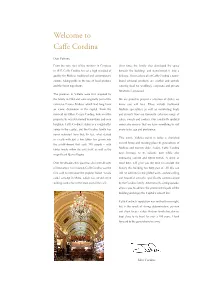

Welcome to Caffe Cordina

Welcome to Caffe Cordina Dear Patrons, From the very start of the business in Cospicua Over time, the family also developed the space in 1837, Caffe Cordina has set a high standard of beneath the building, and transformed it into a quality for Maltese traditional and contemporary dolceria. This is where all of Caffe Cordina’s name- cuisine, taking pride in the use of local produce brand artisanal products are crafted and outside and the finest ingredients. catering food for weddings, corporate and private functions is prepared. The premises in Valletta were first acquired by the family in 1944 and were originally part of the We are proud to present a selection of dishes we extensive Casino Maltese which had long been know you will love. These include traditional an iconic destination in the capital. From the Maltese specialities as well as comforting treats moment my father, Cesare Cordina, took over the and desserts from our famously-extensive range of property, he was determined to maintain, and even cakes, sweets and cookies. Our constantly updated heighten, Caffe Cordina’s status as a sought-after menu also ensures that we have something to suit venue in the capital, and the Cordina family has every taste, age and preference. never waivered from that. In fact, what started This iconic Valletta outlet is today a cherished as a café with just a few tables has grown into second home and meeting place to generations of the establishment that seats 350 people – with Maltese and tourists alike. Today, Caffe Cordina tables inside within the café itself, as well as the pays homage to its eclectic past while also magnificent Pjazza Regina. -

Joffrey Ballet

Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre tz -< NORTHERN TRUST IS PROUD TO SUPPORT THE DETROIT OPERA. n o -a o 9. ~ I- Z Ll.J :E :r:: u "'"Z Ll.J OPERA RERUNS OF AMERICA'S FUNNIEST HOME INJURIES Sin ce o ur fo unding in 1889, N o rthern Tru st ha s nurtured a cu lture of coring and a commitm ent to invest in the communities we se rve. ~ Northern Trust Bloomfield Hills Grand Rapids Grosse Pointe Forms 248·593·9300 616·233·0834 313·881·1030 northerntrust.com Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre BR(iVO CONTENTS 2006 Fall Season The Official Magazine of the Detroit Opera House BRAVO is a Michigan Opera Theatre WELCOME publication Letter from David DiChiera ...... ........ .... ........... .... ..................... 4 Dave Blackburn, Managing Editor Contributors ON STAGE David DiChiera Karen VanderKloot DiChiera Dracula .......................................................................................... 6 Ella M. Fredrickson Behind the Dracula Legend ...... ... ....... .. .... .. ......... .. .. .. .. ... ... ... .... l 0 DeBose Heyward Roberto Mauro Elizabeth Miller Porgy &: Bess ....................... ..... ...... .. .. .. .. .... .. ....... .... ....... .... ........ 12 Judith Slotkin Notes from Catfish Row .... .... ........... ......... .... ... ..... .... .... .... ....... 16 Publisher Echo Publications, Inc. The Barber of Seville ............ .... ... ...... .. ............ ...... .. .... .. ... ...... .. 18 Royal Oak, Michigan What's in a Premiere? .. .. ........................... .... ......... .... .... .... ....... 20 www.echopublications.com -

BLUE HOUR Cocktails

BLUE HOUR Cocktails € Start your evening with a little kick… Enjoy a refreshing cocktail during our blue hour from 18:00 till 19:00 you can benefit from this offer on these specially priced & selected drinks. Kin-ito 4.50 Havana club rum, Kinnie, mint leaves, lime juice, brown sugar Kinnie Sour 4.50 Aperol, Kinnie, lime juice, sugar syrup Pimm’s Kinnie 4.50 Pimm’s No. 1, Kinnie, lime juice, sliced orange, mara- schino cherries Classic Margarita 4.50 Tequila, triple sec, lime juice Mojito 4.50 Rum, mint leaves, lime, sugar, soda Piña Colada 4.50 Dark rum, coconut milk liqueur, pineapple juice Caipirinha 4.50 Cachaça, brown sugar & lime Classic Martini 4.50 Gordon’s gin, extra dry martini Cosmopolitan 4.50 Vodka, cointreau, lime & cranberry juice Catalina Smoothie 4.50 Strawberry syrup, banana, honey & orange COFFEE & Specialities € Americano 3.00 Finely ground and pressure brewed Decaffeinated Americano 2.75 Espresso 2.50 Dark robust coffee Decaffeinated Espresso 2.75 Double Espresso 4.00 Double serving of dark robust coffee Caffè Mocha 3.75 Espresso topped with chocolate milk, served in a glass Cappuccino 3.25 Rich espresso topped with frothy milk Espresso Macchiato 2.75 Small rich espresso topped with frothy hand steamed milk Latte Macchiato 4.00 Rich espresso, steamed milk topped with frothy fresh milk, served in a glass ‘San Lawrenz’ Hot Chocolate 4.25 Iced Coffee 6.00 Dark robust coffee with vanilla ice cream and crushed ice Althaus Loose Tea 4.25 Althaus Pyra Pack Tea 3.75 Afternoon Tea is served till 18:00 Maltese Coffee 3.75 Jamaican Coffee 5.75 Rum, tia maria, brown sugar, coffee & cream MILKSHAKES 6.00 Homemade ice-cream & fresh milk plus your choice of flavour. -

The Clinton 3P* VOL XXXI.—NO

The Clinton 3P* VOL XXXI.—NO. 17. ST. JOHNS, MICH, THURSDAY MORNING, MARCH WHOLE NO Brevities. GEN. SPAULDING'S APPOINTMENT Changed Business Quarters. A fine 16x20 portrait, gloss or pla- VOTERS ATTENTION! Is Conceded by HU Friend* to be a Fore Woodruff & Tromp, the young and THE VILLAGE ELECTION tino finish, for only $1.00, with orders, OVID VILLAGE ELECTION progressive dealers in boots and shoes, gone 4*oucI union. at Stage's East Side Studio. Few Word* From the Chairmen of the on Monday last moved from their late —Read on our back page the attract A Washington special to the Associ Union Silver Partie*. quarters to the store so long occupied by ated Press, dated March 8, says : Three Men on the Silver Ticket ive offers of low prices at Heller’s ba Spirited “Wet” and “ Dry” To the Silver Voters of Clinton Thomas Dudley’s harness business, first zaar, head of Clinton avenue, west side. “The Michigan senators are preparing Elected. Contest. to confer with each other regarding the County : north of O. P. DeWitt’s grocery. The The common council of the city of room has been thoroughly overhauled Lansing has adopted the Abbott voting applications of a large number of Mich We desire to address a few words to igan men who are seeking federal offices you. aud fitted up especially to their liking machine to be used first at the election outside the state. They are united in REPUBLICAN MAJORITIES GREATLY TWO TICKETS IN THE FIELD-PKO- The cause of bimetallism is gaining and for their line of trade. -

Sparkling White Rosè Red Sweet

wine wine wine wine wine wine 02 sparkling 03-07 white 08 rosè 09-13 red 14 sweet sparkling wines B Martini Royale Bianco €21.50 Pale with an alluring sparkle. Light vanilla notes of Bianco are cut with the crisp Glera grape of the Martini Prosecco. Producer Martini —— Region Italy —— Grape Variety Glera C Martini Royale Rosato €21.50 Spiced fruity aromas finished with an orange wedge. A swirling combination to bring out Rosato’s refreshing citrus notes. Producer Martini —— Region Italy —— Grape Variety Glera D Prosecco ‘Extra Dry’ €18.00 Fruity nose of apples and citrus fruit; crisp, fragrant and refined palate with delicious hints of ripe apples and apricots. Producer Val d’Oca —— Region Veneto, Italy —— Grape Variety Glera E Cassar de Malte ‘Brut’ €38.00 Cassar de Malte is Malta’s only Brut created entirely using the ‘Methode Traditionnelle.’ Its bouquet is typically complex with lingering floral and fruity notes. It is invitingly rich, full in taste and complemented by its pleasant natural sparkle. Producer Marsovin —— Region Malta —— Grape Variety Chardonnay F Franciacorta Rosé ‘Brut’ €37.00 Brilliant pale pink and nuances of pale pink, fine and persistent perlage, transparent. Intense, clean, pleasing and refined, starts with hints of apple, cherry and raspberry followed by aromas of bread crust, strawberry, banana, tangerine, pear and hints of vanilla. Effervescent and crisp attack, however balanced by alcohol, good body, intense flavours, agreeable. Producer Monogram —— Region Lombardy, Italy —— Grape Variety Chardonnay & Pinot Noir G Champagne Brut ‘Mosaïque’ €70.00 Chardonnay and Pinot Meunier. A balanced assemblage of the three grape varieties disclosing a succession of elegant and harmonious sensations, a fresh maturity, supple and refined lines. -

L Day Brêkfa

SANDWICH & BURGERS Fruit Toast w/ butter (v) 7.5 Smoked Salmon Fillet w/ avocado salsa, a poached egg, 21 salmon caviar, wild rocket on toasted ciabatta Sourdoughl day / Multigrain brêkfa / Gluten Free / Brioche w/ 6.5 your choice of condiment vegemite, peanut butter, honey Club Sandwich w/ grilled chicken, crispy bacon, avocado, 19.9 or fruit jam brie cheese, garlic aioli on brioche bread & chips Eggs Your Way poached, scrambled or fried on 10.9 Philly’s Steak Sandwich w/ chargrilled beef, mustard, 19.9 sourdough / multigrain / brioche / gluten free American cheese on soft bread & chips RFC Chicken Burger w/ crumbed chicken breast, cheese, 19.9 siracha mayo, baby cos on a brioche bun & chips Pulled Beef 5 Beef Burger w/ bacon, garlic mayo, cos, tomato relish on 19.9 a brioche bun & chips Smoked Salmon 5 Pork & Fennel Sausage 4 Smoked Bacon 4 Chorizo 4 SALADS Avocado ½ 4 Coconut Chicken Salad w/ diced mango, crushed 19.9 Extra Toast 2 peanuts, red cabbage, Vietnamese mint & Palm sugar dressing Mushrooms 3 Grilled Tomato 3 EXTRAS Chicken Caesar Salad w/ baby cos, crispy bacon, 19.9 Spinach 3 croutons, parmesan, a poached egg & caesar dressing Feta 3 Hash Brown 3 Egg 3 cSTEAKShoice of: red wine jus / pepper sauce / mushroom sauce / garlic butter (gf) Black Angus Scotch Fillet 250gm w/ chips & salad (gf) 36.5 Berry Chia Pudding w/ red wine poached pear, fresh 15.9 berries, granola & vanilla frozen yoghurt (v) (gf) Black Angus Porterhouse 250gm w/ chips & salad (gf) 34.3 Acai Bowl w/ home baked granola, sliced banana, 16.9 shredded coconut,