Skull – Ii Dermatocranium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOVASAURUS BOULEI, an AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN from the UPPER PERMIAN of MADAGASCAR by P.J

99 Palaeont. afr., 24 (1981) HOVASAURUS BOULEI, AN AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN FROM THE UPPER PERMIAN OF MADAGASCAR by P.J. Currie Provincial Museum ofAlberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T5N OM6, Canada ABSTRACT HovasauTUs is the most specialized of four known genera of tangasaurid eosuchians, and is the most common vertebrate recovered from the Lower Sakamena Formation (Upper Per mian, Dzulfia n Standard Stage) of Madagascar. The tail is more than double the snout-vent length, and would have been used as a powerful swimming appendage. Ribs are pachyostotic in large animals. The pectoral girdle is low, but massively developed ventrally. The front limb would have been used for swimming and for direction control when swimming. Copious amounts of pebbles were swallowed for ballast. The hind limbs would have been efficient for terrestrial locomotion at maturity. The presence of long growth series for Ho vasaurus and the more terrestrial tan~saurid ThadeosauTUs presents a unique opportunity to study differences in growth strategies in two closely related Permian genera. At birth, the limbs were relatively much shorter in Ho vasaurus, but because of differences in growth rates, the limbs of Thadeosau rus are relatively shorter at maturity. It is suggested that immature specimens of Ho vasauTUs spent most of their time in the water, whereas adults spent more time on land for mating, lay ing eggs and/or range dispersal. Specilizations in the vertebrae and carpus indicate close re lationship between Youngina and the tangasaurids, but eliminate tangasaurids from consider ation as ancestors of other aquatic eosuchians, archosaurs or sauropterygians. CONTENTS Page ABREVIATIONS . ..... ... ......... .......... ... ......... ..... ... ..... .. .... 101 INTRODUCTION . -

Il/I,E,Icanjluseum

il/i,e,icanJluseum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 1870 FEBRUARY 26, 1958 The Role of the "Third Eye" in Reptilian Behavior BY ROBERT C. STEBBINS1 AND RICHARD M. EAKIN2 INTRODUCTION The pineal gland remains an organ of uncertain function despite extensive research (see summaries of literature: Pflugfelder, 1957; Kitay and Altschule, 1954; and Engel and Bergmann, 1952). Its study by means of pinealectomy has been hampered in the higher vertebrates by its recessed location and association with large blood vessels which have made difficult its removal without brain injury or serious hemorrhage. Lack of purified, standardized extracts, improper or inadequate extrac- tion techniques (Quay, 1956b), and lack of suitable assay methods to test biological activity have hindered the physiological approach. It seems probable that the activity of the gland varies among different species (Engel and Bergmann, 1952), between individuals of the same species, and within the same individual. This may also have contrib- uted to the variable results obtained with pinealectomy, injection, and implantation experiments. The morphology of the pineal apparatus is discussed in detail by Tilney and Warren (1919) and Gladstone and Wakely (1940). Only a brief survey is presented here for orientation. In living vertebrates the pineal system in its most complete form may be regarded as consisting of a series of outgrowths situated above the third ventricle in the roof of the diencephalon. In sequence these outgrowths are the paraphysis, dorsal sac, parapineal, and pineal bodies. The paraphysis, the most I University of California Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. -

Bibliography of Arizona Vertebrate Paleontology

Heckert, A.B., and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2005, Vertebrate Paleontology in Arizona. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin No. 29. 168 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ARIZONA VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY CALEB LEWIS1, ANDREW B. HECKERT2 and SPENCER G. LUCAS1 1New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 1801 Mountain Road NW, Albuquerque, NM 87104-1375; 2Department of Geology, Appalachian State University, ASU Box 32067, Boone, NC 28608-2067 Abstract—We provide a bibliography of Arizona vertebrate paleontology that consits of approximately 625 references covering vertebrate occurrences ranging in age from Devonian to Holocene. Not surpris- ingly, references to Triassic and Neogene vertebrates are the most numerous, reflecting the particular strengths of the Arizona record. We break the bibliography down into various taxic groups and provide a complete, unified bibliography at the end of the paper. Keyworks: Arizona, bibliography, fossil, vertebrate, paleontology INTRODUCTION tracks from the Paleozoic and Mesozoic of the state. The Lower Permian Coconino and Lower Jurassic Navajo sandstones in Our aim in presenting a bibliography of Arizona vertebrate northern Arizona are especially known for their vertebrate and paleontology is to provide a valuable research tool for all those invertebrate trackways. conducting vertebrate paleontology research in Arizona. This Abstracts were generally omitted from the bibliography bibliography will also be made available as individual, download - partly to save space, but also due to the difficulty in tracking able Endnote® libraries on the New Mexico Museum of Natural down all published abstracts, many of which exist only in the History and Science paleontological resources website (www. “gray literature” and are duplicated by subsequent full-length nmfossils.org). -

Anatomy and Relationships of the Triassic Temnospondyl Sclerothorax

Anatomy and relationships of the Triassic temnospondyl Sclerothorax RAINER R. SCHOCH, MICHAEL FASTNACHT, JÜRGEN FICHTER, and THOMAS KELLER Schoch, R.R., Fastnacht, M., Fichter, J., and Keller, T. 2007. Anatomy and relationships of the Triassic temnospondyl Sclerothorax. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 52 (1): 117–136. Recently, new material of the peculiar tetrapod Sclerothorax hypselonotus from the Middle Buntsandstein (Olenekian) of north−central Germany has emerged that reveals the anatomy of the skull and anterior postcranial skeleton in detail. Despite differences in preservation, all previous plus the new finds of Sclerothorax are identified as belonging to the same taxon. Sclerothorax is characterized by various autapomorphies (subquadrangular skull being widest in snout region, ex− treme height of thoracal neural spines in mid−trunk region, rhomboidal interclavicle longer than skull). Despite its pecu− liar skull roof, the palate and mandible are consistent with those of capitosauroid stereospondyls in the presence of large muscular pockets on the basal plate, a flattened edentulous parasphenoid, a long basicranial suture, a large hamate process in the mandible, and a falciform crest in the occipital part of the cheek. In order to elucidate the phylogenetic position of Sclerothorax, we performed a cladistic analysis of 18 taxa and 70 characters from all parts of the skeleton. According to our results, Sclerothorax is nested well within the higher stereospondyls, forming the sister taxon of capitosauroids. Palaeobiologically, Sclerothorax is interesting for its several characters believed to correlate with a terrestrial life, although this is contrasted by the possession of well−established lateral line sulci. Key words: Sclerothorax, Temnospondyli, Stereospondyli, Buntsandstein, Triassic, Germany. -

Late Cretaceous) of Morocco : Palaeobiological and Behavioral Implications Remi Allemand

Endocranial microtomographic study of marine reptiles (Plesiosauria and Mosasauroidea) from the Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of Morocco : palaeobiological and behavioral implications Remi Allemand To cite this version: Remi Allemand. Endocranial microtomographic study of marine reptiles (Plesiosauria and Mosasauroidea) from the Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of Morocco : palaeobiological and behavioral implications. Paleontology. Museum national d’histoire naturelle - MNHN PARIS, 2017. English. NNT : 2017MNHN0015. tel-02375321 HAL Id: tel-02375321 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02375321 Submitted on 22 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Ecole Doctorale Sciences de la Nature et de l’Homme – ED 227 Année 2017 N° attribué par la bibliothèque |_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| THESE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DU MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Spécialité : Paléontologie Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Rémi ALLEMAND Le 21 novembre 2017 Etude microtomographique de l’endocrâne de reptiles marins (Plesiosauria et Mosasauroidea) du Turonien (Crétacé supérieur) du Maroc : implications paléobiologiques et comportementales Sous la direction de : Mme BARDET Nathalie, Directrice de Recherche CNRS et les co-directions de : Mme VINCENT Peggy, Chargée de Recherche CNRS et Mme HOUSSAYE Alexandra, Chargée de Recherche CNRS Composition du jury : M. -

Redalyc.Ontogeny of the Cranial Bones of the Giant Amazon River

Acta Scientiarum. Biological Sciences ISSN: 1679-9283 [email protected] Universidade Estadual de Maringá Brasil Gonçalves Vieira, Lucélia; Quagliatto Santos, André Luiz; Campos Lima, Fabiano Ontogeny of the cranial bones of the giant amazon river turtle Podocnemis expansa Schweigger, 1812 (Testudines, Podocnemididae) Acta Scientiarum. Biological Sciences, vol. 32, núm. 2, 2010, pp. 181-188 Universidade Estadual de Maringá .png, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=187114387012 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative DOI: 10.4025/actascibiolsci.v32i2.5777 Ontogeny of the cranial bones of the giant amazon river turtle Podocnemis expansa Schweigger, 1812 (Testudines, Podocnemididae) Lucélia Gonçalves Vieira*, André Luiz Quagliatto Santos and Fabiano Campos Lima Laboratório de Pesquisas em Animais Silvestres, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Av. João Naves De Avila, 2121, 38408-100, Uberlandia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. *Author for correspondence. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. In order to determine the normal stages of formation in the sequence of ossification of the cranium of Podocnemis expansa in its various stages of development, embryos were collected starting on the 18th day of natural incubation and were subjected to bone diaphanization and staining. In the neurocranium, the basisphenoid and basioccipital bones present ossification centers in stage 19, the supraoccipital and opisthotic in stage 20, the exoccipital in stage 21, and lastly the prooptic in stage 24. Dermatocranium: the squamosal, pterygoid and maxilla are the first elements to begin the ossification process, which occurs in stage 16. -

Variability of the Parietal Foramen and the Evolution of the Pineal Eye in South African Permo-Triassic Eutheriodont Therapsids

The sixth sense in mammalian forerunners: Variability of the parietal foramen and the evolution of the pineal eye in South African Permo-Triassic eutheriodont therapsids JULIEN BENOIT, FERNANDO ABDALA, PAUL R. MANGER, and BRUCE S. RUBIDGE Benoit, J., Abdala, F., Manger, P.R., and Rubidge, B.S. 2016. The sixth sense in mammalian forerunners: Variability of the parietal foramen and the evolution of the pineal eye in South African Permo-Triassic eutheriodont therapsids. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61 (4): 777–789. In some extant ectotherms, the third eye (or pineal eye) is a photosensitive organ located in the parietal foramen on the midline of the skull roof. The pineal eye sends information regarding exposure to sunlight to the pineal complex, a region of the brain devoted to the regulation of body temperature, reproductive synchrony, and biological rhythms. The parietal foramen is absent in mammals but present in most of the closest extinct relatives of mammals, the Therapsida. A broad ranging survey of the occurrence and size of the parietal foramen in different South African therapsid taxa demonstrates that through time the parietal foramen tends, in a convergent manner, to become smaller and is absent more frequently in eutherocephalians (Akidnognathiidae, Whaitsiidae, and Baurioidea) and non-mammaliaform eucynodonts. Among the latter, the Probainognathia, the lineage leading to mammaliaforms, are the only one to achieve the complete loss of the parietal foramen. These results suggest a gradual and convergent loss of the photoreceptive function of the pineal organ and degeneration of the third eye. Given the role of the pineal organ to achieve fine-tuned thermoregulation in ecto- therms (i.e., “cold-blooded” vertebrates), the gradual loss of the parietal foramen through time in the Karoo stratigraphic succession may be correlated with the transition from a mesothermic metabolism to a high metabolic rate (endothermy) in mammalian ancestry. -

622-2014Lectureweek5

BIOLOGY 622 – FALL 2014 BASAL AMNIOTA - STRUCTURE AND PHYLOGENY WEEK – 5 EUREPTILIA – “PROTOROTHYRIDIDAE AND ARAEOSCELIDIA S. S. SUMIDA INTRODUCTION Now that we have determined the distinction of Eureptilia and Parareptilia, and used Captorhinidae as the model of the basalmost family of eureptilians, we may now address the remaining primitive members of Eureptilia. Of course Eureptilia is a huge group, including numerous extinct groups, and all sorts of extant taxa including extant diapsids – lizards and snakes, turtles (which are probably highly derived diapsids) the remaining extant archosauromorphs – the crocodilians and the birds (derived from saurischian therapod dinosaurs). The group that was “displaced” by the Captorhinidae as the most primitive of reptilians has a somewhat complicated history. Recall that Carroll (1969) designated the family Romeriidae as the group from which all other amniotes arose. The group was named for genus Romeria, originally named by Lewellyn Price with two species – Romeria texana and R. pricei (both from the Lower Permian of Texas). In the 1970s, Heaton (1979) removed Romeria from Romeriidae, suggesting they were better placed in the Captorhinidae. This left Romeriidae without its namesake, so the name reverted to Protorothyrididae. (Carroll persisted in calling this group the “Protorothyridae”.) Nonetheless, the monophyly of the Protorothyrididae was assumed. This was in part because most workers that “included” the Protorothyrididae in any phylogenetic analyses, usually did so only by using a single representative genus to represent the entire family – usually Protorthyris or Paleothyris. For example, in the illustration following, Heaton and Reisz (1986) used only Captorhinus to represent Captorhinidae, Protorothyris to represent Protorothyrididae, and Petrolacosaurus to represent basal Diapsida. -

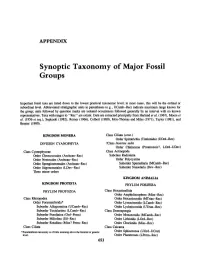

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Jaw Suspension

JAW SUSPENSION Jaw suspension means attachment of the lower jaw with the upper jaw or the skull for efficient biting and chewing. There are different ways in which these attachments are attained depending upon the modifications in visceral arches in vertebrates. AMPHISTYLIC In primitive elasmobranchs there is no modification of visceral arches and they are made of cartilage. Pterygoqadrate makes the upper jaw and meckel’s cartilage makes lower jaw and they are highly flexible. Hyoid arch is also unchanged. Lower jaw is attached to both pterygoqadrate and hyoid arch and hence it is called amphistylic. AUTODIASTYLIC Upper jaw is attached with the skull and lower jaw is directly attached to the upper jaw. The second arch is a branchial arch and does not take part in jaw suspension. HYOSTYLIC In modern sharks, lower jaw is attached to pterygoquadrate which is in turn attached to hyomandibular cartilage of the 2nd arch. It is the hyoid arch which braces the jaw by ligament attachment and hence it is called hyostylic. HYOSTYLIC (=METHYSTYLIC) In bony fishes pterygoquadrate is broken into epipterygoid, metapterygoid and quadrate, which become part of the skull. Meckel’s cartilage is modified as articular bone of the lower jaw, through which the lower jaw articulates with quadrate and then with symplectic bone of the hyoid arch to the skull. This is a modified hyostylic jaw suspension that is more advanced. AUTOSTYLIC (=AUTOSYSTYLIC) Pterygoquadrate is modified to form epipterygoid and quadrate, the latter braces the lower jaw with the skull. Hyomandibular of the second arch transforms into columella bone of the middle ear cavity and hence not available for jaw suspension. -

Callibrachion and Datheosaurus, Two Historical and Previously Mistaken Basal Caseasaurian Synapsids from Europe

Callibrachion and Datheosaurus, two historical and previously mistaken basal caseasaurian synapsids from Europe FREDERIK SPINDLER, JOCELYN FALCONNET, and JÖRG FRÖBISCH Spindler, F., Falconnet, J., and Fröbisch, J. 2016. Callibrachion and Datheosaurus, two historical and previously mis- taken basal caseasaurian synapsids from Europe. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61 (3): 597–616. This study represents a re-investigation of two historical fossil discoveries, Callibrachion gaudryi (Artinskian of France) and Datheosaurus macrourus (Gzhelian of Poland), that were originally classified as haptodontine-grade sphenaco- dontians and have been lately treated as nomina dubia. Both taxa are here identified as basal caseasaurs based on their overall proportions as well as dental and osteological characteristics that differentiate them from any other major syn- apsid subclade. As a result of poor preservation, no distinct autapomorphies can be recognized. However, our detailed investigations of the virtually complete skeletons in the light of recent progress in basal synapsid research allow a novel interpretation of their phylogenetic positions. Datheosaurus might represent an eothyridid or basal caseid. Callibrachion shares some similarities with the more derived North American genus Casea. These new observations on Datheosaurus and Callibrachion provide new insights into the early diversification of caseasaurs, reflecting an evolutionary stage that lacks spatulate teeth and broadened phalanges that are typical for other caseid species. Along with Eocasea, the former ghost lineage to the Late Pennsylvanian origin of Caseasauria is further closed. For the first time, the presence of basal caseasaurs in Europe is documented. Key words: Synapsida, Caseasauria, Carboniferous, Permian, Autun Basin, France, Intra-Sudetic Basin, Poland. Frederik Spindler [[email protected]], Dinosaurier-Park Altmühltal, Dinopark 1, 85095 Denkendorf, Germany. -

The Cranial Anatomy and Relationships of the Synapsid Varanosaurus (Eupelycosauria: Ophiacodontidae) from the Early Permian of Texas and Oklahoma

ANNALS OF CARNEGIE MUSEUM VOL 64, NUM~. 2, ..... 99-133 12 MAy 1995 THE CRANIAL ANATOMY AND RELATIONSHIPS OF THE SYNAPSID VARANOSAURUS (EUPELYCOSAURIA: OPHIACODONTIDAE) FROM THE EARLY PERMIAN OF TEXAS AND OKLAHOMA DAVID S BERMAN Curator, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology ROBERT R. REISZI JOHN R. BoLT2 DIANE ScoTTI ABsTRACT The cranial anatomy of the Early Permian synapsid Varanosaurus is restudied on the basis of preY iously described specimens from Texas, most importantly the holotype of the type species V. aCUlirostris. and a recently discovered, excellently preserved specimen from Oklahoma. Cladistic analysis of the Eupelycosauria, using a data matrix 0(95 characters, provides the following hYPOthesis of relationships of VaraIJosaurus: I) VaraIJosaurus is a member of the family Ophiacodontidae; 2) of the ophiacodonlid genera included in the analysis, Varanosaurus and OpniacodOIJ share a more recent common ancestor than either does with the more primitive Arcna('()tnyris; and 3) a clade containing the progressively more derived taxa Edaphosauridae, H aplodus. and Sphenacodontoidea (Sphena- . codontidae plus Therapsida), together with Varanopseidae and Caseasauria, are progressively more distant outgroups or sister taxa to Ophiacodontidae. A revised diagnosis is given for VaralJosQurus. INTRODUCTION Published accounts of the Early Permian synapsid Varanosaurus have been limited almost entirely to rather brief descriptions based on a few poorly preserved andlor incomplete skeletons collected from the Lower Permian of north-central Texas. The holotype of the type species Varanosaurus acutirostris was described originally by Broili (1904) and consists of an incomplete articulated skeleton (BSPHM 1901 XV 20), including most importantly the greater portion of the skull, collected from the Arroyo Formation, Clear Fork Group.