Wholesale Must-Offer Remedies: International Examples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded in 2002, Some of of 13.7 Million Euros

01 02 03 M6 explores today In 2002, M6 feted its 15th year, the age when an adult and responsible future M6 has been a shareholder of the TPS satellite bouquet since its launching starts to crystallize. An occasion that a television network can celebrate and has also participated in its development. only if it has managed to match consistency with the will to move ahead. The prospects are encouraging for a group with the backing of a strong As the network with France’s second largest advertising market share, in generalist television network. The year’s activity, described in these pages, just a few years M6 has succeeded in earning our industry’s highest tributes. is the best illustration. Late off starting blocks, our network has worked patiently, and without arro- gance, to win over increasingly demanding viewers. Jean Drucker Throughout these fifteen years, with growing audiences and an ever expan- ding share of the advertising market, M6 has never ceased to make its pro- grams more rewarding, boosting its investment in diversity, discovery, and culture, particularly music and magazines, where our network has played a major role. M6 is also the network where new talent and formats are first tried out. 04 Ambitious objectives With its strong operating performance of 2002, M6 proved its capacity to diversification activities, all orientations which enable the Group to adapt to resist in a difficult market. its market. Finally, M6 has the necessary financial resources to consider every investment opportunity. First, it confirmed the station’s standing as the second most watched chan- nel among viewers under 50, with an audience share equal to 2001, which With its one thousand permanent staff members, all motivated by a corpo- had been an exceptional year. -

Bilan De L'économie Des Chaînes Payantes Année 2009

Bilan de l’économie des chaînes payantes Année 2009 les bilans du CSA Décembre 2010 CONSEIL SUPÉRIEUR DE L ’AUDIOVISUEL Direction des programmes Direction des études et de la prospective Service de l’information et de la documentation Bilan de l’économie des chaînes payantes Année 2009 Bilan 2009 de l’économie des chaînes payantes Comme chaque année, le CSA a dressé le bilan de l’économie des chaînes payantes. Cette analyse, qui ne prend pas en compte la chaîne Canal+, porte sur 99 des 117 chaînes payantes existant fin 2009. Elle fait notamment apparaître que près de 42 % des foyers équipés d’un téléviseur étaient à cette date abonnés à une offre multichaîne payante. Synthèse Un bilan qui porte sur 99 chaînes payantes Le bilan réalisé par le CSA entend par télévision payante tout service qui n’est accessible que par le biais d’un abonnement, que ce soit pour une offre globale, couplée ou non avec d’autres services (internet, téléphone), ou pour des services vendus à l’unité. Cette définition ne tient donc pas compte du financement des services. Au 31 décembre 2009, le nombre des services payants conventionnés ou autorisés en langue française (hors Canal+) diffusés sur le câble, le satellite et l’ADSL en France métropolitaine était de 117, contre 116 en 2008. Parmi ceux-ci, 6 étaient autorisés et 111 conventionnés. Toutefois, les données statistiques qui font l’objet de l’étude portent sur 99 services édités par 58 sociétés. 13 sociétés éditent plusieurs services chacune - Canal J (3 chaînes) : Canal J, June et Tiji ; - Disney Channel -

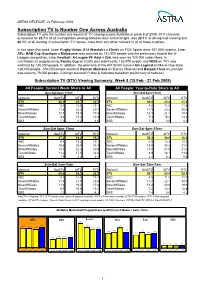

Subscription TV Is Number One Across Australia Subscription TV Was the Number One Source of TV Viewing Across Australia in Week 8 of 2009

MEDIA RELEASE- 23 February 2009 Subscription TV Is Number One Across Australia Subscription TV was the number one source of TV viewing across Australia in week 8 of 2009. STV channels accounted for 23.7% of all metropolitan viewing between 6am and midnight, was 22.1% of all regional viewing and 60.1% of all viewing in subscription TV homes, more than any other network in all of those markets. In live sport this week, Live: Rugby Union: S14 Waratahs v Chiefs on FOX Sports drew 167,000 viewers, Live: AFL: NAB Cup Hawthorn v Melbourne was watched by 142,000 people and the preliminary final of the A- League competition, Live: Football: A-League PF Adel v Qld, was seen by 124,000 subscribers. In entertainment programming, Family Guy on FOX8 was watched by 153,000 people and NCIS on TV1 was watched by 135,000 people. In addition, the premiere of the Will Smith movie I Am Legend on Movie One drew 128,000 people, 106,000 people watched Hannah Montana on Disney Channel and Bargain Hunt on Lifestyle was seen by 79,000 people. (Listings overleaf; Friday & Saturday based on preliminary schedules). Subscription TV (STV) Viewing Summary: Week 8 (15 Feb - 21 Feb 2009) All People: Current Week Share to All All People: Year-to-Date Share to All Sun-Sat 6am-12mn Sun-Sat 6am-12mn Network NatSTV MTV RTV Network NatSTV MTV RTV STV 60.1 23.7 22.1 STV 60.0 23.8 21.8 ABC 5.1 12.6 13.1 ABC 4.5 11.5 11.8 Seven/Affiliates 11.8 22.2 20.7 Seven/Affiliates 11.9 22.3 20.3 Nine/Affiliates 12.1 19.0 17.4 Nine/Affiliates 14.3 21.1 19.7 Ten/Affiliates 9.1 17.2 13.3 Ten/Affiliates -

Décision N° 11-D-12 Du 20 Septembre 2011 Relative Au Respect Des

RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE Décision n° 11-D-12 du 20 septembre 2011 relative au respect des engagements figurant dans la décision autorisant l’acquisition de TPS et CanalSatellite par Vivendi Universal et Groupe Canal Plus L’Autorité de la concurrence, Vu la décision du ministre de l’économie, des finances et de l’industrie du 30 août 2006, autorisant l’acquisition de TPS et CanalSatellite par Vivendi Universal et Groupe Canal Plus sous réserve de l’ensemble des engagements pris par ces sociétés le 24 août 2006, ensemble l’avis émis sur l’opération par le Conseil de la concurrence le 13 juillet 2006 ; Vu la lettre, enregistrée le 4 juillet 2008 sous le numéro 08/0075 A, par laquelle le ministre de l’économie, de l’industrie et de l’emploi a saisi le Conseil de la concurrence pour avis sur l’exécution des engagements souscrits par Vivendi Universal et Groupe Canal Plus ; Vu la décision n° 09-SO-01 du 28 octobre 2009 par laquelle l’Autorité s’est saisie d’office de l’exécution des engagements souscrits par Vivendi Universal et Groupe Canal Plus (affaire enregistrée sous le numéro 09/0116 R) ; Vu le livre IV du code de commerce, et notamment son article L. 430-8 ; Vu l’avis de l’Autorité de régulation des communications électroniques et des postes n° 2010-0381 du 15 avril 2010 ; Vu l’avis du Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel n° 2010-13 du 27 mai 2010 ; Vu les rapports du mandataire relatifs à l’état de réalisation des engagements souscrits par le Groupe Canal Plus ; Vu les observations présentées par Vivendi Universal, Groupe Canal Plus et le commissaire du Gouvernement ; Vu les autres pièces du dossier ; Les rapporteures, le rapporteur général adjoint, le commissaire du Gouvernement et les représentants des sociétés Vivendi Universal et Groupe Canal Plus entendus lors de la séance de l’Autorité de la concurrence du 24 mai 2011 ; Adopte la décision suivante : I. -

Subscription TV Homes Only Week 10 2019 (03/03/2019 - 09/03/2019) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests

Consolidated National Subscription TV Share and Reach National Share and Reach Report - Subscription TV Homes only Week 10 2019 (03/03/2019 - 09/03/2019) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests Channel Share Of Viewing Reach Weekly 000's % TOTAL PEOPLE ABC 5.8 1900 ABCKIDS/COMEDY 1.0 714 ABC ME 0.2 259 ABC NEWS 0.5 480 Seven + AFFILIATES 14.5 3056 7TWO + AFFILIATES 0.8 522 7mate + AFFILIATES 1.3 893 7flix + AFFILIATES 0.4 385 7food network + AFFILIATES 0.2 125 Nine + AFFILIATES* 16.8 3432 GO + AFFILIATES* 1.8 1100 Gem + AFFILIATES* 0.7 478 9Life + AFFILIATES* 0.7 482 10 + AFFILIATES* 7.5 2745 10 Bold + AFFILIATES* 0.7 607 10 Peach + AFFILIATES* 0.9 823 Sky News on WIN + AFFILIATES* 0.2 225 SBS 2.0 1398 SBS VICELAND 0.5 726 SBS Food 0.5 465 NITV 0.1 189 111 0.7 559 111 +2 0.2 242 13TH STREET 0.9 398 13TH STREET+2 0.2 139 [V] 0.1 187 [V] +2 0.0 122 A&E 0.6 451 A&E+2 0.3 232 Animal Planet 0.2 224 ARENA 0.7 532 ARENA+2 0.2 188 BBC First 0.8 505 BBC Knowledge 0.4 324 beIN SPORTS 1 0.0 55 beIN SPORTS 2 0.0 72 beIN SPORTS 3 0.1 115 Binge 0.1 201 Boomerang 0.1 85 BoxSets 1.5 450 Cartoon Network 0.2 146 CBeebies 0.1 89 COMEDY CHANNEL 0.4 451 COMEDY CHANNEL+2 0.2 205 Country Music Channel 0.0 64 crime + investigation 1.2 514 Discovery Channel 0.7 607 Discovery Channel+2 0.2 293 Discovery Kids 0.0 30 Discovery Science 0.3 246 Discovery Turbo 0.3 229 Excludes Tasmania *Affiliation changes commenced July 1, 2016. -

Press Release FRANCE TELECOM and TPS LAUNCH DIGITAL

Press release FRANCE TELECOM AND TPS LAUNCH DIGITAL TELEVISION OVER TELEPHONE LINES France Télécom and TPS (TF1: 66% - M6: 34%) have signed a strategic agreement which will enable TPS to offer digital television services using ADSL technology over France Télécom’s network from December 2003. ADSL technology makes it possible simultaneously to phone, connect to broadband internet services and receive the TPS platform of channels, provisionally named TPSL, as well as programmes-on- demand and interactive services. All customers will need to do to receive TPSL will be to take out a video access subscription from France Télécom (ADSL video access and terminal set connected to the television) and select one of the packages offered by TPS. Programmes-on-demand will be offered by France Télécom using the ‘kiosk’ model already familiar to Minitel users. These new services from France Télécom and TPS will be launched in Lyon in December 2003, and then in Paris in the spring of 2004, before gradually being rolled out to other French cities. They will be available through approved outlets, such as specialist stores, department stores, installers and France Télécom shops. Thierry Breton, CEO of France Télécom, stated, "This agreement with TPS is a concrete example of France Télécom’s strategy of forging industrial partnerships that will benefit its customers. It represents a major innovation in extending the use of broadband connections beyond the internet and in developing new ways of distributing audiovisual content. It has been made possible by the quality of our networks and by the technical expertise that France Télécom has gained in the area of image transmission, an area which offers substantial growth potential, particularly for fixed-line telephone services". -

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout

Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout Those channels whose viewing data is not shown below as being available are included in the channel group ‘Other STV’ From 28 From 11 From 27 From 19th From 28th From 26th From 27th From 26th From 25th From 24th From 1st From 31st Channel Dec 2003 July 2004 Feb 2005 June 2005 Aug 2005 Nov 2006 May 2007 Aug 2007 Nov 2007 Feb 2008 June 2008 May 2009 111 Hits 9 Adults Only Adventure One AIR Audio Channels Al Jazeera Animal Planet 9999 9999999 Antenna Arena TV 999999999999 Arena TV+2* * 999999999 Art Arabic Aurora Community Channel* * Aust Christian Channel BBC World 999 Biography Channel* * 9999999 Bloomberg Television 999 Boomerang 99999 Box Office* * Box Office Adults Only Select* * Box Office Main Event* * Box Office Preview* * Cartoon Network 999999999999 Channel V Channel V2 999999 Club (V) CNBC 999999999999 CNN International Comedy Channel 999999999999 Comedy Channel+2* * 9 99 Country Music Channel 999999 Crime & Investigation Network* * 9999999 Discovery Channel 9999 9999999 Discovery Home and Health* * 999 Discovery Science* * 999 Discovery Travel & Adventure* * 9999999 Disney Channel 999999999999 E!* * 9 999 ESPN 999999999999 Eurosportnews EXPO Fashion TV FOX8 999999999999 FOX8+2 9 99 * Subscription TV data is only available on an aggregate market level. Page 1 © All Rights Reserved 2009 Regional Subscription TV Channels Timetable of Breakout Those channels whose viewing data is not shown below as being available are included in the channel group ‘Other STV’ From 28 From 11 -

2004 Annual Report

Couv I,II,III,IV-dos9mm GB 20/04/05 12:32 Page 1 2004 Annual Report Télévision Française 1 A public limited company “Société Anonyme” with a share capital of €42,811,946 326 300 159 RCS Nanterre TF1 1, quai du Point du Jour 92656 Boulogne Cedex / France Tel. : (33) 1 41 41 12 34 Internet : http://www.tf1.fr 2004 Annual Report Couv I,II,III,IV-dos9mm GB 20/04/05 12:32 Page 2 Main subsidiaries’ and participations’ adresses 1, quai du Point-du-Jour TPS CINETOILE 92656 Boulogne-Billancourt Cedex - France TPS JEUNESSE TF1 PUBLICITE (www.tf1pub.fr) TPS MOTIVATION TF1 FILMS PRODUCTION TPS TERMINAUX TF1 DIGITAL TPS INTERACTIF ALMA PRODUCTIONS TPS SERVICES TFM DISTRIBUTION (www.tfmdistribution.com) MULTIVISION YAGAN PRODUCTIONS MULTIVISION GESTION CIBY 2000 SENT TFOU (www.tfou.fr) SOCIETE D’EXPLOITATION DU MULTIPLEX R6 - SMR6 3, rue Gaston-et-René-Caudron HISTOIRE 92448 Issy-les-Moulineaux Cedex - France USHUAIA TV EUROSPORT (www.eurosport.com) EUROSALES 305, avenue le Jour-se-Lève EUROSPORT France 92656 Boulogne-Billancourt Cedex - France e-TF1 120, avenue Charles-de-Gaulle TF1 ENTREPRISES ( www.tf1licences.com) 92200 Neuilly-sur-Seine - France SOCIETE D’EXPLOITATION ET DE DOCUMENTAIRES TF6 (www.tf6.fr) ODYSSEE (www.odyssee.com) SERIE CLUB (www.serieclub.fr) COMPAGNIE INTERNATIONALE DE COMMUNICATION - CIC Quai Péristyle - 56100 Lorient - France CIBY DA TV BREIZH (www.tvbreizh.fr) 9, rue Maurice-Mallet 3, rue du Commandant-Rivière - 75008 Paris - France 92130 Issy-les-Moulineaux - France TCM DA UNE MUSIQUE (www.unemusique.fr) TF1 VIDEO (www.tf1video.fr) -

Inside This Issue

Lake Pointe Subdivision Inside this Issue: • National Night Out 2019 Party Pics ........................... Pages 5-6 • Holiday Trash Collection Schedules .......................... Page 8 • NTRCA is seeking Neighborhood Reps!..................... Page 11 • Harvest Fest & Car Show is November 2nd ............... Page 18 ASSOCIATIONOUR COMMUNITY UPDATES Need to Report a Maintenance Issue? If you notice a maintenance issue within the community, send an email to [email protected]. Your message will be routed to our maintenance department NEW TERRITORY RESIDENTIAL for a speedy response. Feel free to snap a pic with your COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION (NTRCA) phone to illustrate the issue you are reporting, and provide details about the exact location. 6101 Homeward Way Sugar Land, TX 77479 Is Your Street Light Out? www.newterritory.org If you notice a street light out, write down the 6-digit number on the light pole. Then report the outage to CenterPoint Energy at 713-207- 2222 or report it online at http://cnp.centerpointenergy.com/outage. Association Phone Numbers Association Office 281-565-0616 Are You a New Resident in the Community? Association Fax 281-565-0188 If so, welcome to New Territory! Please stop by the Association office The Club 281-565-1070 for a New Homeowner¶s Guide, and fill out forms to register for use of The Club Fax 281-565-1130 The Club facility. Then drop by The Club and check out the pool and Tennis Pro Shop 281-565-5355 all of the other wonderful amenities that are available to you. For a preview of amenities, visit the Parks and Recreation section on the newterritory.org website. -

Personalisation for Smart Personal Assistants

Personalisation for Smart Personal Assistants Joshua Cole Matt Gray John Lloyd Computer Sciences Laboratory Computer Sciences Laboratory Computer Sciences Laboratory The Australian National University The Australian National University The Australian National University Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Kee Siong Ng Computer Sciences Laboratory The Australian National University Email: [email protected] Abstract— This paper is concerned with personalisation of II. AN INFOTAINMENT DEMONSTRATOR smart personal assistants by machine learning techniques. The application of these ideas to an infotainment demonstrator is In this section, we describe the infotainment demonstrator discussed in detail. The symbolic, on-line machine learning being developed, concentrating on the TV recommender. techniques used are described. Also experimental results, which demonstrate that a high level of personalisation can be achieved The infotainment demonstrator is a multi-agent system that by this approach, are presented. combines a number of related functionalities concerning in- formation search and entertainment. The agents that comprise the demonstrator and that are at least partly implemented I. INTRODUCTION include a TV recommender, a movie recommender, a news agent, a search agent, and a diary agent. In addition, there is a coordinator agent that has the responsibility of handling This paper describes some recent results from the “Machine interactions between the user and the various agents in the Learning for the Smart Personal Assistant” project in the demonstrator. We also plan to include a music recommender Smart Internet Technology Cooperative Research Centre. The because the technology that would be needed to implement aim of the project is to apply machine learning techniques it is the same as the other agents and, given the extraor- to building adaptive agents, especially user agents that fa- dinary current interest in the IPOD and similar devices, we cilitate interaction between a user and the Internet. -

Digital TV Antenna Systems

Digital TV Antenna Systems 2 0 0 8 Handbook Non-Mandatory Document Digital TV Antenna Systems Free-to-Air digital TV in buildings with shared antenna systems 2008 2nd Edition Digital TV Antenna Systems Disclaimer The Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) and the participating Governments are committed to enhancing the availability and dissemination of information relating to the built environment. Where appropriate, the ABCB seeks to develop non-regulatory solutions to building related issues. This Handbook on Digital TV Antenna Systems (the Handbook) is non-mandatory and is designed to assist in making such information on this topic readily available. However, neither the ABCB, the participating Governments, nor the groups which have endorsed or been involved in the development of the Handbook, accept any responsibility for the use of the information contained in the Handbook and make no guarantee or representation whatsoever that the information is an exhaustive treatment of the subject matters contained therein or is complete, accurate, up-to-date or relevant as a guide to action for any particular purpose. All liability for any loss, damage, injury or other consequence, howsoever caused (including without limitation by way of negligence) which may arise directly or indirectly from use of, or reliance on, this Handbook, is hereby expressly disclaimed. Users should exercise their own skill and care with respect to their use of this Handbook. In any important matter, users should carefully evaluate the scope of the treatment of the particular subject matter, its completeness, accuracy, currency, and relevance for their purposes, and should obtain appropriate professional advice relevant to their particular circumstances. -

Top 100 Pay Television Programs Total Individuals Week 25, 2009 (14/06/2009 - 20/06/2009) Round to Nearest Thousand 5 City Metro Prepared by SEVEN NETWORK RESEARCH

Top 100 Pay Television Programs Total Individuals Week 25, 2009 (14/06/2009 - 20/06/2009) Round to Nearest Thousand 5 City Metro Prepared by SEVEN NETWORK RESEARCH TV Item Description (grouped) Channel 5 City Metro 1 LIVE: FOOTBALL: WORLD CUP QUALIFIER AUST V FOX SPORTS 1 288,000 JAPAN 2 LIVE: AFL ADELAIDE V NORTH MELBOURNE FOX SPORTS 1 195,000 3 LIVE: AFL HAWTHORN V BRISBANE LIONS FOX SPORTS 1 163,000 4 LIVE: NRL EELS V WESTS TIGERS FOX SPORTS 2 141,000 5 LIVE: NRL COWBOYS V ROOSTERS FOX SPORTS 2 121,000 6 LIVE: FOOTBALL: WORLD CUP QUALIFIER POST FOX SPORTS 1 108,000 GAME 7 LIVE: AFL PRE GAME SHOW FOX SPORTS 1 98,000 8 LIVE: FOOTBALL: WORLD CUP QUALIFIER PRE FOX SPORTS 1 88,000 GAME 9 LIVE: NRL RAIDERS V SHARKS FOX SPORTS 2 88,000 10 LIVE: AFL: ON THE COUCH FOX SPORTS 1 85,000 11 LIVE: RUGBY UNION: TEST MATCH FOX SPORTS 3 72,000 12 AUSTRALIA'S NEXT TOP MODEL FOX8 65,000 13 LIVE: AFL TEAMS FOX SPORTS 1 60,000 14 LIVE: NRL MONDAY POST GAME SHOW FOX SPORTS 2 59,000 15 NCIS TV1 56,000 16 MYSTERY MEN SHOWTIME Greats 54,000 17 LIVE: NRL SATURDAY PRE GAME SHOW FOX SPORTS 2 52,000 18 THE SIMPSONS FOX8 50,000 19 FAMILY GUY FOX8 46,000 20 LIVE: MOTORSPORT: MOTOGP RND 6, CATALUNA FOX SPORTS 2 45,000 21 AFL: BEFORE THE BOUNCE FOX SPORTS 1 45,000 22 CASPER MEETS WENDY Disney Channel 40,000 23 THE DOMINO PRINCIPLE FOX Classics 39,000 24 GRAND DESIGNS LifeStyle Channel 38,000 25 THE SEX CHAMBER Crime & Investigation 38,000 26 JONAS Disney Channel 37,000 27 TWO AND A HALF MEN FOX8 37,000 28 EYE OF THE NEEDLE FOX Classics 36,000 29 THE MAN FROM THE ALAMO