THE HORNET the Newsletter of the 100 Squadron Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

Date Pilot Aircraft Serial No Station Location 6/1/1950 Eggert, Wayne W

DATE PILOT AIRCRAFT SERIAL_NO STATION LOCATION 6/1/1950 EGGERT, WAYNE W. XH-12B 46-216 BELL AIRCRAFT CORP, NY RANSIOMVILLE 3 MI N, NY 6/1/1950 LIEBACH, JOSEPH G. B-29 45-21697 WALKER AFB, NM ROSWELL AAF 14 MI ESE, NM 6/1/1950 LINDENMUTH, LESLIE L F-51D 44-74637 NELLIS AFB, NV NELLIS AFB, NV 6/1/1950 YEADEN, HUBERT N C-46A 41-12381 O'HARE IAP, IL O'HARE IAP 6/1/1950 SNOWDEN, LAIRD A T-7 41-21105 NEW CASTLE, DE ATTERBURY AFB 6/1/1950 BECKLEY, WILLIAM M T-6C 42-43949 RANDOLPH AFB, TX RANDOLPH AFB 6/1/1950 VAN FLEET, RAYMOND A T-6D 42-44454 KEESLER AFB, MS KEESLER AFB 6/2/1950 CRAWFORD, DAVID J. F-51D 44-84960 WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB, OH WEST ALEXANDRIA 5 MI S, OH 6/2/1950 BONEY, LAWRENCE J. F-80C 47-589 ELMENDORF AAF, AK ELMENDORF AAF, AK 6/2/1950 SMITH, ROBERT G F-80B 45-8493 FURSTENFELDBRUCK AB, GER NURNBERG 6/2/1950 BEATY, ALBERT C F-86A 48-245 LANGLEY AFB, VA LANGLEY AFB 6/2/1950 CARTMILL, JOHN B F-86A 48-293 LANGLEY AFB, VA LANGLEY AFB 6/2/1950 HAUPT, FRED J F-86A 49-1026 KIRTLAND AFB, NM KIRTLAND AFB 6/2/1950 BROWN, JACK F F-86A 49-1158 OTIS AFB, MA 8 MI S TAMPA FL 6/3/1950 CAGLE, VICTOR W. C-45F 44-87105 TYNDALL FIELD, FL SHAW AAF, SC 6/3/1950 SCHOENBERGER, JAMES H T-7 43-33489 WOLD CHAMBERLIAN FIELD, MN WOLD CHAMBERLAIN FIELD 6/3/1950 BROOKS, RICHARD O T-6D 44-80945 RANDOLPH AFB, TX SHERMAN AFB 6/3/1950 FRASER, JAMES A B-50D 47-163 BOEING FIELD, SEATTLE WA BOEING FIELD 6/4/1950 SJULSTAD, LLOYD A F-51D 44-74997 HECTOR APT, ND HECTOR APT 6/4/1950 BUECHLER, THEODORE B F-80A 44-85153 NAHA AB, OKI 15 MI NE NAHA AB 6/4/1950 RITCHLEY, ANDREW J F-80A 44-85406 NAHA AB, OKI 15 MI NE NAHA AB 6/4/1950 WACKERMAN, ARNOLD G F-47D 45-49142 NIAGARA FALLS AFB, NY WESTCHESTER CAP 6/5/1950 MCCLURE, GRAVES C JR SNJ USN-27712 NAS ATLANTA, GA MACDILL AFB 6/5/1950 WEATHERMAN, VERNON R C-47A 43-16059 MCCHORD AFB, WA LOWRY AFB 6/5/1950 SOLEM, HERMAN S F-51D 45-11679 HECTOR APT, ND HECTOR APT 6/5/1950 EVEREST, FRANK K YF-93A 48-317 EDWARDS AFB, CA EDWARDS AFB 6/5/1950 RANKIN, WARNER F JR H-13B 48-800 WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB, OH WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB 6/6/1950 BLISS, GERALD B. -

Call Book 1920 - 1930

Jack Hum CALL BOOK 1920 - 1930 Jack Hum, G5UM’s, Callbook. Researched and Compiled by: Deryk Wills, G3XKX. This PDF conversion by: Brian Perrett, MW0GKX. 5........... Foreword......By Brian Perrett. 5........... Foreword.......By Deryk Wills. 7........... G2 calls. 19............ G3 calls. 27............ G4 calls. 34............ G5 calls. 46............ G6 calls 58............ G8 calls. 66............ About the author....By Deryk Wills. (reproduced fron the Leicestershire Repeater Group Website) Foreword by Brian Perrett. I was writing a web page about “Famous Radio Amateurs and their callsigns” for the Highfields Amateur Radio Club when I received, via e-mail, a collection of text documents sent by my local repeater keeper, GW8ERA. I had a quick look and thought that it might be interesting to add this record of times gone. As they were received in a plain text format I thought it would be better if they were presented in a more favourable way in this technological age, so I have spent some time converting the plain text files into this PDF book. I also have tried to add a little about the man himself, but I have been unable to find out much about Jack. What I have found is in the “About the Author” at the back of this book. I have not edited the entries so, while some of the calls may still be vaild, do not use the data here for contact purposes. I hope this document goes some way to Dreyk’s wishes in the last line of his foreword. If anyone can send me more information about Jack Hum, G5UM, for inclusion in this book, I can be contacted via email at: [email protected]. -

An Aviation Guide Through East Lindsey Locating Active RAF Stations and Former Airfield Sites Contents

An aviation guide through East Lindsey locating active RAF stations and former airfield sites Contents Map To Grimsby Holton Contents Le Clay NORTH COATES N Tetney North Cotes Marshchapel DONNA NOOK MAP NOT DRAWN TO SCALE A1 North 8 Fulstow East Lindsey | East Lindsey Grainsthorpe Thoresby North Somercotes LUDBOROUGH Covenham Reservoir A16 Binbrook Saltfleet A 1031 | East Lindsey Utterby Alvingham KELSTERN North Fotherby Cockerington THEDDLETHORPE A631 Saltfleetby To Market Louth LUDFORD MAGNA Grimoldby St. Peter Theddlethorpe St. Helen Rasen South South Cockerington Elkington Theddlethorpe A157 B1200 MANBY All Saints Mablethorpe Donington Legbourne on Bain Abbreviations North Coates BBMF Visitor Centre A157 Trusthorpe Little Withern Sutton PAGE 4 PAGES 18 & 19 PAGES 30 & 31 A16 Cawthorpe STRUBBYThorpe on Sea Cadwell Woodthorpe East Barkwith Maltby Sandilands MARKET STAINTON le Marsh Introduction Spilsby Lincolnshire Aviation A5 To A Scamblesby 10 Wragby 2 Lincoln Aby PAGE 5 Ruckland 4 PAGES 20 & 21 Heritage Centre A1111 Bilsby Belchford PAGES 32 & 33 A158 Anderby Bardney Strubby Alford Creek Tetford Brinkhill Mumby PAGES 6 & 7 PAGES 22 & 23 Baumber Hemingby Chapel Thorpe Camp Visitor Minting Somersby Mawthorpe St. Leonards A1 Hogsthorpe Centre A 02 West Ashby Bag Enderby Harrington 1 8 Coningsby 6 Woodhall Spa PAGES 34 & 35 Horncastle Willoughby PAGES 8 & 9 Hagworthingham PAGES 24 & 25 BARDNEY Thimbleby Addlethorpe BUCKNALL Partney INGOLDMELLS Horsington B1195 Orby Petwood Hotel Raithby East Kirkby Other Locations Gunby PAGE 36 Stixwould 191 WINTHORPE PAGES 10 & 11 B1 3 SPILSBY Halton 5 MOORBY Hundleby Burgh le Marsh PAGES 26 & 27 Roughton A1 Holegate Old Bolingbroke BURGH ROAD Toynton Great Kelstern The Cottage Museum WOODHALL SPA East Steeping Skegness Coastal Bombing Revesby EASTWe KIRKBYst Keal PAGES 12 & 13 PAGE 37 B1 Thorpe St. -

RAFCT Had Worked Hard with the Totalling £755,866

THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CHARITABLE TRUST ANNUAL REVIEW 2017-18 TRUST HELPS JUNIOR RANKS REACH CENTENARY MILESTONE 2 3 LOOKING BACK CHAIRMEN’S A SUMMARY OF GRANTS THAT WERE AWARDED IN THE PREVIOUS FINANCIAL YEAR (2016-17) BUT FOREWORD CAME TO FRUITION IN THE CURRENT YEAR (2017/18) During the year ending February 28, 2017, Trustees approved a £7,000 grant to help Girlguiding South West develop a new set of The past 12 months have proved a busy period for the RAF that develop leadership and enterprise. We were delighted to see activity badges, designed to get more young Charitable Trust and its trading companies as Trustees and Board it gaining considerable traction with exceptional submissions, women ‘in the air’. The new resource and members made preparations to play a full part in the Royal Air resulting in awards of £15,000 and £10,000 being granted last activity pack, called ‘In The Air’ offers Force’s Centenary celebrations. year for expeditions to Peru and Guyana. members the opportunity to earn up to seven new Science, Technology, Engineering and The RAF Centenary celebrations and the RAF100 Appeal were During the past year, Trustees have supported grant applications Mathematics (STEM) badges though a number launched in November 2017. RAFCT had worked hard with the totalling £755,866. This included giving the green light to an of aviation related activities called SWEBOTS. RAF and the other three main RAF charities: RAFA, the RAF RAFFCA bid to purchase a second Tecnam training aircraft, the Benevolent Fund and the RAF Museum over the preceding 12 largest, single award made by Trustees since the charity was months to collectively deliver an RAF100 Appeal that would established in 2005. -

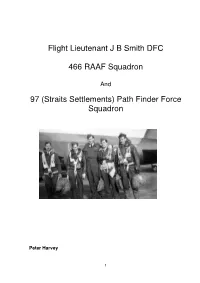

Flight Lieutenant JB Smith DFC 466 RAAF

Flight Lieutenant J B Smith DFC 466 RAAF Squadron And 97 (Straits Settlements) Path Finder Force Squadron Peter Harvey 1 Forward Flight Lieutenant Smith DFC was the pilot / captain of my late uncle’s Lancaster, JB708 OF-J, 97 Path Finder Force (PFF) Squadron, which was shot down on the 11th May 1944 on a 5 Group bombing operation targeting the Lille railway infrastructure. F/L Smith was the Deputy Controller for this sortie and therefore the crew would have been one of the most experienced in the Squadron at that time. The crew were: • 414691 F/L JB Smith DFC RNZAF, Pilot • 537312 Sgt AR Rowlands RAFVR, Flight Engineer • 134059 F/O AR Weston RAFVR, Navigator • 138589 F/L LC Jones DFC RAFVR, Bomb Aimer • 174353 P/O DED Harvey DFM RAFVR, Wireless Operator • R/85522 W/O JR Chapman DFC RCAF, Upper Air Gunner • J/17360 F/O SG Sherman RCAF, Rear Air Gunner There are two websites dedicated to the crew: http://greynomad7.wix.com/a-97-sqn-pff-aircrew#!home/mainPage http://tribalgecko.wix.com/lancasterjb708#!jb708 The following data provides a short history of just one Bomber Command pilot and his crews. F/L Smith served with 466 RAAF Squadron at Leconfield in North Yorkshire, became a flying instructor after 29 operational flights and then volunteered to join 97 PFF Squadron stationed at RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire. He was a member of the Royal New Zealand Air Force and carried out his flying training in Canada. The data is taken from varying sources listed in the bibliography. -

Hemswell Cliff Parish Council Action Plan 2019-2020

Document History: Adopted on 8 May 2017 Last reviewed: May 2019 Hemswell Cliff Parish Council Action Plan 2019-2020 1 Overview of the Parish Hemswell Cliff is a great place to live. We have an excellent school, a lovely rural setting and a thriving business community. Hemswell Cliff is a village and civil parish in the West Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. It is situated on the A631 road between Caenby Corner and Gainsborough and on the Lincoln Cliff escarpment. Within the Parish is the hamlet of Spital-in- theStreet, the village centred round the former RAF base. According to the 2001 Census it had a population of 683, in 2011 the population had risen 794. RAF Hemswell was located on the site from 1937 until it closed in 1967. Hemswell Cliff Primary School is in the village. The airfield site was subsequently redeveloped into a private trading estate and the RAF married quarters into a residential area which became a newly created civil parish of Hemswell Cliff. By mid-2008 there was no longer RAF presence on the site, which became entirely civilian. The site's old H-Block buildings contain an antique centre, shops, a garden centre, hairdresser, used book shop and cafés. A large recycling plant and grain processing facility are also located on the site. The Parish also has number of farms operating within it as well as a large amount of high quality farming land. Hemswell Cliff Parish Council Action Plan Hemswell Cliff Parish Council strives to work on behalf of parishioners on the issues that matter to the village. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2010

Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund Trustees’ Report and Accounts for the year ending 31 December 2010 Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund Our Vision Every member of the RAF family should have access to support whenever they need it. Our Mission We are the RAF’s leading welfare charity, providing financial, practical and emotional support to all members of the RAF family. We are here to help serving and former members of the RAF, as well as their partners and dependants, whenever they need us. Contents Chairman’s Report 02 Controller’s Report 04 Principals, Trustees and 06 Senior Management Team Trustees’ Report 07 Principal Office and 12 Professional Advisers Independent Auditor’s Report 13 Consolidated Statement 14 of Financial Activities Balance Sheet 16 Consolidated Cash 17 Flow Statement Notes to the 18 Financial Statements Endowment Funds 28 Restricted Income Funds 29 Grants to Third Parties 30 ©UK MOD Crown Copyright 2011 RAFBF Report and Accounts 01 A safety net in uncertain times: looking back on 2010 “It was clear to us that base closures and redundancies would create new challenges and ask even more of the Service community.” Chairman’s Report The Royal Air Force family experienced significant We also consolidated our relationships with changes in 2010 as the new government outlined many other RAF charities, notably the Polish a programme of spending cuts designed to reduce Air Force Association. our national deficit. We were also privileged to participate in many The Strategic Defence and Security Review was events held to mark the 70th anniversary of the an important part of this, affecting most serving Battle of Britain. -

Raaf Personnel Serving on Attachment in Royal Air Force Squadrons and Support Units

Cover Design by: 121Creative Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6012 email. [email protected] www.121creative.com.au Printed by: Kwik Kopy Canberra Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6066 email. [email protected] www.canberra.kwikkopy.com.au Compilation Alan Storr 2006 The information appearing in this compilation is derived from the collections of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia. Author : Alan Storr Alan was born in Melbourne Australia in 1921. He joined the RAAF in October 1941 and served in the Pacific theatre of war. He was an Observer and did a tour of operations with No 7 Squadron RAAF (Beauforts), and later was Flight Navigation Officer of No 201 Flight RAAF (Liberators). He was discharged Flight Lieutenant in February 1946. He has spent most of his Public Service working life in Canberra – first arriving in the National Capital in 1938. He held senior positions in the Department of Air (First Assistant Secretary) and the Department of Defence (Senior Assistant Secretary), and retired from the public service in 1975. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree (Melbourne University) and was a graduate of the Australian Staff College, ‘Manyung’, Mt Eliza, Victoria. He has been a volunteer at the Australian War Memorial for 21 years doing research into aircraft relics held at the AWM, and more recently research work into RAAF World War 2 fatalities. He has written and published eight books on RAAF fatalities in the eight RAAF Squadrons serving in RAF Bomber Command in WW2. -

Air Commodore Arthur

AIR COMMODORE ARTHUR “FATHER” WRAY DSO, MC, DFC & BAR, AFC Arthur “Father” Wray was eft with a permanent limp as decorated fi ve times for his a result of wounds received in gallantry, the span of his active Lthe First World War, Wray was of a similar mould to the legendary service and the combination of Douglas Bader: nothing would stop his decorations amounting to a him from fl ying. Like Bader, too, Wray loathed red unique career in the annals of tape: he was unorthodox and prone RAF history. In the latest in his to attracting his seniors’ displeasure, though it is just such spirited warriors series, Lord Ashcroft examines the that win battles and wars, particularly service of Air Commodore Arthur when they take great care of their less experienced charges. Wray saw Wray DSO, MC, DFC & Bar, AFC. action during the Second World War, time and time again ignoring orders to ABOVE: Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris KCB, OBE, AFC, Air Offi cer Commanding-in- remain grounded, so as to accompany Chief, Bomber Command (Centre), talking his young bomber crews on their fi rst with Air Commodore Arthur Wray DSO, MC, operational sorties. At the same time, DFC & Bar, AFC, (left) and Group Captain Hughie Edwards VC, DSO, DFC, during a he knew full well that his First World visit to 460 Squadron RAAF at Binbrook, 16 War wounds would have prevented September 1943. (Courtesy of the Australian him from baling out of a stricken War Memorial; UK0551) aircraft. Arthur Mostyn Wray was born in Brighton, Sussex, in August 1896. -

Mastery of the Air the Raaf in World War Ii

021 2 WINTER WINGS NO.2 73 VOLUME SHOOTING STAR PHANTOMS IN VIETNAM AMERICA’S FIRST SUCCESSFUL JET AN AUSSIE PILOT'S EXPERIENCE MASTERY OF THE AIR THE RAAF IN WORLD WAR II SECRET FLIGHTS CATALINAS ON THE DANGEROUS 'DOUBLE SUNRISE' ROUTE AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION MAGAZINE defencebank.com.au Special 1800 033 139 edition AF100 Visa Debit card. To celebrate the 100 Year Anniversary of the Royal Australian Air Force, we have launched our special edition Defence Bank AF100 Visa Debit card. Scan the QR code or visit our website for full details. Defence Bank Limited ABN 57 087 651 385 AFSL/Australian Credit Licence 234582. CONTENTS. defencebank.com.au ON THE COVER 1800 033 139 Consolidated PBY Catalina Flying boat VH-PBZ wearing the famous RAAF World War II Black Cat livery. Special Photo: Ryan Fletcher / Shutterstock.com 38 WINGS TEAM WINGS MANAGER Ron Haack EDITOR Sandy McPhie ART DIRECTOR Katie Monin SENIOR ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE CONTENTS Sue Guymer ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE Phil Whiteman wings WINTER 2021 volume 73 / NO.2 edition ASSISTANT EDITORS Mike Nelmes (history) 4 WELCOME MESSAGE John Kindler AO AFC (industry news) 5 MANAGER’S MESSAGE & LETTERS Bob Treloar AO MiD (military aviation) 6 MILITARY AVIATION AF100 Visa Debit card. 12 PRESIDENT'S DESK & CONTACT ASSOCIATION NEWS E [email protected] W wingsmagazine.org 16 INDUSTRY NEWS A RAAFANSW Publications Pty Ltd 22 A GLOBAL WAR To celebrate the 100 Year Anniversary Salamander Bay LPO, PO Box 656 History of the RAAF, part 2 Salamander Bay 2317 30 COMBAT EXPERIENCE of the Royal Australian Air Force, Flying Phantoms in Vietnam PRINTED BY: WHO Printing, Regional Printer we have launched our special edition of the Year, National Print Awards 2020. -

Hemswell Cliff Parish

West Lindsey District Council Community Profile Hemswell Cliff Parish March 2009 Contents Page Introduction 1 Population 2 Deprivation 7 Economy 10 Infrastructure 13 Recreation and Leisure 16 Crime 17 Glossary 19 It should be noted that there are no statistics included for Health and Education. With regard to health, this is mainly due to the non-release of health information for a small area such as Hemswell Cliff that could lead to possible identification of individuals. Test results of pupils by residency are also not available for publication at such a low level of geography for similar reasons. Introduction he parish of Hemswell Cliff is located in the district of West Lindsey, about 12 miles north of T Lincoln, just off the A15, and is a unique mix of industrial, agricultural, residential and retail properties. The parish was formed when the former RAF Hemswell was closed and most of the property changed to private ownership. The former base buildings now house one of the largest antique centres in Europe and other businesses ranging from grain storage and testing facilities to second hand book shops and a garden centre. On Sundays the site hosts a huge open market and carboot sale. © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Lincolnshire County Council. 100025370 1 Community Profile — Hemswell Cliff Parish Population Key Facts • The population of Hemswell Cliff parish • Hemswell Cliff parish residents aged over 65 decreased by 7.6% during the period 2001- account for 5.6% of the population, 2005 compared with a district increase of just considerably lower than the district average of under 7%.