Curve Sketching and Relative Maxima and Minima the Goal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

A Collection of Problems in Differential Calculus

A Collection of Problems in Differential Calculus Problems Given At the Math 151 - Calculus I and Math 150 - Calculus I With Review Final Examinations Department of Mathematics, Simon Fraser University 2000 - 2010 Veselin Jungic · Petra Menz · Randall Pyke Department Of Mathematics Simon Fraser University c Draft date December 6, 2011 To my sons, my best teachers. - Veselin Jungic Contents Contents i Preface 1 Recommendations for Success in Mathematics 3 1 Limits and Continuity 11 1.1 Introduction . 11 1.2 Limits . 13 1.3 Continuity . 17 1.4 Miscellaneous . 18 2 Differentiation Rules 19 2.1 Introduction . 19 2.2 Derivatives . 20 2.3 Related Rates . 25 2.4 Tangent Lines and Implicit Differentiation . 28 3 Applications of Differentiation 31 3.1 Introduction . 31 3.2 Curve Sketching . 34 3.3 Optimization . 45 3.4 Mean Value Theorem . 50 3.5 Differential, Linear Approximation, Newton's Method . 51 i 3.6 Antiderivatives and Differential Equations . 55 3.7 Exponential Growth and Decay . 58 3.8 Miscellaneous . 61 4 Parametric Equations and Polar Coordinates 65 4.1 Introduction . 65 4.2 Parametric Curves . 67 4.3 Polar Coordinates . 73 4.4 Conic Sections . 77 5 True Or False and Multiple Choice Problems 81 6 Answers, Hints, Solutions 93 6.1 Limits . 93 6.2 Continuity . 96 6.3 Miscellaneous . 98 6.4 Derivatives . 98 6.5 Related Rates . 102 6.6 Tangent Lines and Implicit Differentiation . 105 6.7 Curve Sketching . 107 6.8 Optimization . 117 6.9 Mean Value Theorem . 125 6.10 Differential, Linear Approximation, Newton's Method . 126 6.11 Antiderivatives and Differential Equations . -

WORKSHEET - Mathematics (Advanced) 1

Questions WORKSHEET - Mathematics (Advanced) 1. Geometry and Calculus, 2UA 2017 HSC 4 MC 10. Geometrical Applications of Differentiation Curve Sketching and The Primitive Function The function is defined for Teacher: James Butterworth On this interval, Exam Equivalent Time: 94.5 minutes (based on HSC allocation of 1.5 Which graph best represents ? minutes approx. per mark) (A) y (B) y x a b x a b x (C) y (D) y HISTORICAL CONTRIBUTION x x T10 Geometry and Calculus is the single largest topic within the Mathematics a b a b course, contributing 15.0% to each paper, on average, in the last 10 years. x This topic has been split into three sub-categories: 1-Maxima and Minima (5.3%), 2-Curve Sketching and The Primitive Function (7.6%), and 3-Tangents and Normals (2.1%). 2017 HSC ANALYSIS - What to expect and common pitfalls Curve Sketching and The Primitive Function (7.6%). The most popular curve is easily the cubic, asked 7 times since 2003, including 2015. Note that we have to go back 10 years before cubics have been left off the HSC two years in a row in this topic area. Cubics were left off in the 2016 exam... enough said. Sketches of polynomials of degree 4 are the second most popular, asked in 2007, 2008, 2012 and 2016. Focus Area: An examiner favourite in this topic area requires students to switch between f(x) and f´(x) for a given function, either graphically or by using an equation. This has been tested every year in recent times, except not in 2015 or 2016, in questions worth 1-5 marks. -

Understanding Basic Calculus

Understanding Basic Calculus S.K. Chung Dedicated to all the people who have helped me in my life. i Preface This book is a revised and expanded version of the lecture notes for Basic Calculus and other similar courses offered by the Department of Mathematics, University of Hong Kong, from the first semester of the academic year 1998-1999 through the second semester of 2006-2007. It can be used as a textbook or a reference book for an introductory course on one variable calculus. In this book, much emphasis is put on explanations of concepts and solutions to examples. By reading the book carefully, students should be able to understand the concepts introduced and know how to answer questions with justification. At the end of each section (except the last few), there is an exercise. Students are advised to do as many questions as possible. Most of the exercises are simple drills. Such exercises may not help students understand the concepts; however, without practices, students may find it difficult to continue reading the subsequent sections. Chapter 0 is written for students who have forgotten the materials that they have learnt for HKCEE Mathe- matics. Students who are familiar with the materials may skip this chapter. Chapter 1 is on sets, real numbers and inequalities. Since the concept of sets is new to most students, detail explanations and elaborations are given. For the real number system, notations and terminologies that will be used in the rest of the book are introduced. For solving polynomial inequalities, the method will be used later when we consider where a function is increasing or decreasing as well as where a function is convex or concave. -

Chapter 5: Curve Sketching

5 Curve Sketching Whether we are interested in a function as a purely mathematical object or in connection with some application to the real world, it is often useful to know what the graph of the function looks like. We can obtain a good picture of the graph using certain crucial information provided by derivatives of the function and certain limits. º½ ÅÜÑ Ò ÅÒÑ A local maximum point on a function is a point (x,y) on the graph of the function whose y coordinate is larger than all other y coordinates on the graph at points “close to” (x,y). More precisely, (x,f(x)) is a local maximum if there is an interval (a,b) with a<x<b and f(x) f(z) for every z in both (a,b) and the domain of f. Similarly, ≥ (x,y)is a local minimum point if it has locally the smallest y coordinate. Again being more precise: (x,f(x)) is a local minimum if there is an interval (a,b) with a<x<b and f(x) f(z) for every z in both (a,b) and the domain of f. A local extremum is either ≤ a local minimum or a local maximum. Local maximum and minimum points are quite distinctive on the graph of a function, and are therefore useful in understanding the shape of the graph. In many applied problems we want to find the largest or smallest value that a function achieves (for example, we might want to find the minimum cost at which some task can be performed) and so identifying maximum and minimum points will be useful for applied problems as well. -

14 Further Calculus 14 FURTHER CALCULUS

Chapter 14 Further Calculus 14 FURTHER CALCULUS Objectives After studying this chapter you should • be able to find the second derivatives of functions; • be able to use calculus to find maximum or minimum of functions; • be able to differentiate composite functions or 'function of a function'; • be able to differentiate the product or quotient of two functions; • be able to use calculus in curve sketching. 14.0 Introduction You should have already covered the material in Chapters 8, 11 and 12 before starting this chapter. By now, you will already have met the ideas of calculus, both differentiation and integration, and you will have used the techniques developed in the earlier chapters to solve problems. This section extends the range of problems you can solve, including finding the greatest or least value of a function and differentiating complicated functions. y 14.1 Rate of change of the y = x 3 + 3x 2 − 9x − 4 gradient The sketch opposite shows the graph of 3 2 0 x y = x + 3x − 9x − 4 . You have already seen that the derivative of this function is dy given by dx dy = 2 + − dy 3x 6x 9. = 3x 2 + 6x − 9 dx dx 0 x This is also illustrated opposite. 265 Chapter 14 Further Calculus dy The gradient function, , is also a function of x, and can be d 2 y dx 2 differentiated again to give the second differential dx d 2 y = 6x + 6 dx 2 2 d y 0 x = 6x + 6 . dx 2 Again this is illustrated opposite. Exercise 14A d 3 y 1. -

MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE Geometry

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 100 648 SE 018 119 AUTHOR Yates, Robert C. TITLE Curves and Their Properties. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Inc., Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 259p.; Classics in Mathematics Education, Volume 4 AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Inc., 1906 Association Drive, Reston, Virginia 22091 ($6.40) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Analytic Geometry; *College Mathematics; Geometric Concepts; *Geometry; *Graphs; Instruction; Mathematical Enrichment; Mathematics Education;Plane Geometry; *Secondary School Mathematics IDENTIFIERS *Curves ABSTRACT This volume, a reprinting of a classic first published in 1952, presents detailed discussions of 26 curves or families of curves, and 17 analytic systems of curves. For each curve the author provides a historical note, a sketch orsketches, a description of the curve, a a icussion of pertinent facts,and a bibliography. Depending upon the curve, the discussion may cover defining equations, relationships with other curves(identities, derivatives, integrals), series representations, metricalproperties, properties of tangents and normals, applicationsof the curve in physical or statistical sciences, and other relevantinformation. The curves described range from thefamiliar conic sections and trigonometric functions through tit's less well knownDeltoid, Kieroid and Witch of Agnesi. Curve related - systemsdescribed include envelopes, evolutes and pedal curves. A section on curvesketching in the coordinate plane is included. (SD) U S DEPARTMENT OFHEALTH. EDUCATION II WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCuME N1 ITASOLE.* REPRO MAE° EXACTLY ASRECEIVED F ROM THE PERSON ORORGANI/AlICIN ORIGIN ATING 11 POINTS OF VIEWOH OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE INSTITUTE OF SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL EDUCATION POSITION ORPOLICY $1 loor oiltyi.4410,0 kom niAttintitd.: t .111/11.061 . -

Curve Sketching

106 Chapter 5 Curve Sketching A... ...... .. ... ... ... ... .. ...• ... .. ... ... .. .. ... .. ... ... ... ... .. ... ... .. ... ... .. ... ... .. A ... ... .. ...... ... ... ..A....... .. .. ..... ... ... ....... .......... .. .. .... ... ... ..... ...... .. .. ..... ... ... .... ..... .. ..• ..... .. ... ... ..... .. .. ..... ... ... ... • ..... ... .. ..... .. ... ... .... ... .. ..... ... ... ... ..... ... .. .... ... ... .. ..... ... .. ..... ... ... .. ..... .... .. ........ ... 5 .. ...... ..... .. ... .... .... .. .. ............... .. ... .. .. ... .. .. • .. .. B .. B• .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Curve Sketching .. Figure 5.1.1 Some local maximum points (A) and minimum points (B). If (x,f(x)) is a point where f(x) reaches a local maximum or minimum, and if the derivative of f exists at x, then the graph has a tangent line and the tangent line must be horizontal. This is important enough to state as a theorem, though we will not prove it. THEOREM 5.1.1 Fermat’s Theorem If f(x) has a local extremum at x = a and ′ Whether we are interested in a function as a purely mathematical object or in connection f is differentiable at a, then f (a)=0. with some application to the real world, it is often useful to know what the graph of Thus, the only points at which a function can have a local maximum or minimum the function looks like. We can obtain a good picture of the graph using certain crucial are points at which the derivative is zero, as in the left hand graph in figure 5.1.1, or the information provided by derivatives of the -

THE CALCULUS of CURVE SKETCHING Here Is a Summary of the Analytical Methods of Calculus to Sketch Graphs and Interpret Them

THE CALCULUS OF CURVE SKETCHING Here is a summary of the analytical methods of calculus to sketch graphs and interpret them. It starts with polynomial functions, which are differentiable at all values of their domain (the real numbers). Because of this “good behavior” of polynomials, they are ideal for investigating critical numbers of a function, intervals of increase and decrease, extremes, concavity and points of inflection. Definitions c is a critical number of function f(x) if either f '(c) = 0 or f '(c) does not exist (DNE). A function may have a local extreme at a critical number c (including a non-differentiable cusp or corner), or it may have an inflection point. A function f(x) is (strictly) increasing on an interval I if for each a, b in I, when a < b, f(a) < f(b). A function f(x) is (strictly) decreasing on an interval I if for each a, b in I, when a < b, f(a) > f(b). On an interval where f(x) is increasing, f’(x) > 0; on an interval where f(x) is decreasing, f’(x) < 0. f(x) has a local (relative) maximum at a if f(x) < f(a) for all x in an arbitrarily small interval (called an - neighborhood) of a. f(x) has a local (relative) minimum at a if f(x) > f(a) for all x in an an -neighborhood of a. [Note: A constant function on I has both a local a max and a local min on that interval.] Local maximum and minimum values of a function are called local extremes of the function. -

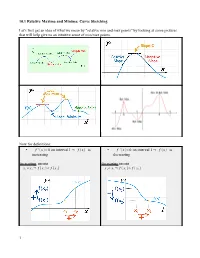

10.1 Relative Maxima and Minima: Curve Sketching

10.1 Relative Maxima and Minima: Curve Sketching Let's first get an idea of what we mean by "relative min and max points" by looking at some pictures that will help give us an intuitive sense of min/max points. Now for definitions: • f '( x)>0 on interval I ⇒ f ( x) is • f '( x)<0 on interval I ⇒ f (x) is increasing decreasing increasing means decreasing means x1<x2 ⇒ f ( x1)< f ( x2) x1< x2 ⇒ f ( x1)> f ( x2) 1 10.1 (continued) critical point: Strategy: A critical point (or x-value), x=c, satisfies f '(c)=0 or f '(c) is undefined To find min/max x-values: (i.e. we say there's a critical point on the curve 1. find where the first derivative is either zero or where the slope is either zero or the slope is undefined. undefined). 2. create a first derivative sign line. 3. interpret the sign line for possible min/max points. Three cases of how the slope can be undefined: 1. There's a moment of vertical slope at that point More vocabulary: on the curve. • relative/local min/max points are determined by the shape of the curve (and 2. The curve is discontinuous at that point (a nothing else, i.e. is it a peak or a valley?) discontinuity could either be a (a) jump, (b) hole • absolute/global min/max points are the or (c) VA). highest point(s) and lowest point(s) on the curve for some given interval (or possibly 3. The point on the curve is too "pointy" (not over the whole domain of the curve); these smooth). -

The Role of Concave and Convex Functions in the Study of Linear & Non-Linear Programming

Dama International Journal of Researchers (DIJR), ISSN: 2343-6743, ISI Impact Factor: 1.018 Vol 3, Issue 05, May, 2018, Pages 15 -29 , Available @ www.damaacademia.com The Role of Concave and Convex Functions in the Study of Linear & Non-Linear Programming Andrew Owusu-Hemeng1, Peter Kwasi Sarpong2, Joseph Ackora-Prah3 1,2,3Department of Mathematics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology,Kumasi,Ghana Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION Convex functions appear in many problems in pure and applied mathematics. They play an extremely important role in the study of both linear and non-linear programming problems. It is very important in the study of optimization. The solutions to these problems lie on their vertices. The theory of convex functions is part of the general subject of convexity, since a convex function is one whose epigraph is a convex set. Nonetheless it is an important theory which touches almost all branches of mathematics. Graphical analysis is one of the first topics in mathematics which requires the concept of convexity. Calculus gives us a powerful tool in recognizing convexity, the second-derivative test. Miraculously, this has a natural generalization for the several variables case, the Hessian test. This project is intended to study the basic properties, some definitions, proofs of theorems and some examples of convex functions. Some definitions like convex and concave sets, affine sets, conical sets, concave functions shall be known. It will also prove that the negation of a convex function will generate a concave function and a concave set is a convex set.