SCRI Annual Report 1996/1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U. K. Geophysical Assembly 12–15 April 1977

Geophys. J. R. astr. SOC. (1977) 49, 245-312 U.K. GEOPHYSICAL ASSEMBLY 12-1 5 APRIL 1977 Downloaded from http://gji.oxfordjournals.org/ at Department of Geophysics James Clerk Maxwell Building at Dept Applied Mathematics & Theoretical Physics on September 15, 2013 University of Edinburgh CONTENTS Preface General (Invited) Lectures Content of Sessions Abstracts Author Index edited by K.M. Creer 246 U.K.G.A. 1977 1 Preface In the spring of 1975 I put the suggestion to the Royal Astronomical Society that a national geophysical meeting be held in U.K. at which a wide variety of subjects would be discussed in parallel sessions along the lines of the annual meetings of the American Geonhysical Union held in Washington. A few U.K. geo- Downloaded from physicists expressed doubts as to whether sufficient interesting geophysics was being done in U.K. to sustain such a meeting. Nevertheless when the question of whether such a national meeting would attract their support was put to geo- physicists in U.K. Universities and Research Institutes, it was apparent that wide support would be forthcoming at the grass-roots level. http://gji.oxfordjournals.org/ At this stage Dr. J. A. Hudson, Geophysical Secretary of the R.A.S., proposed to Council that they should sponsor a national geophysical meeting. They agreed to do this and the U.K. Geophysical Assembly (U.K.G.A.) to be held in the Univer- sity of Edinburgh (U.O.E.) between 12 and 15 April 1977 is the outcome. A Local Organizing Committee was formed with Professor K. -

Mobile Library Route Timetable

MOBILE LIBRARY SERVICE JOIN US AND BEGIN YOUR JOURNEY Week 1 (begins Monday 2nd Oct 2017) VAN 2 Week 2 (begins Monday 9th Oct 2017) VAN 1 Day/Date Location Time Day/Date Location Time Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 2 Oct LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 9 Oct LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 16 Oct ABERLEMNO 11.15-11.45 23 Oct TANNADICE 11.20-11.40 30 Oct LITTLE BRECHIN 12.10-12.30 6 Nov MEMUS 11.55-12.20 13 Nov EDZELL: by PRIMARY SCHOOL 13.20-14.10 20 Nov NORANSIDE 13.05-13.25 27 Nov EDZELL MEMORIAL HALL 14:15-14:45 4 Dec KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 13.45-14.05 11 Dec KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 15.15-15.45 18 Dec INCHBARE 14.20-14.40 25 Dec Holiday NORANSIDE 16.00-16.30 1st Jan Holiday EDZELL: BY PS 14.55-15.45 8 Jan MEMUS 16.40-17.05 EDZELL: INGLIS COURT 15.55-16.20 TANNADICE 17.15-17.45 EDZELL: CHURCH ST 16.30-16.45 WATERSTON ROAD 18.00-18.20 EDZELL: MEMORIAL HALL 16.50-17.20 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.40-19.00 LITTLE BRECHIN 17.55-18.15 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.35-19.00 Tuesdays CORTACHY: by PS 10.15-11.00 Tuesdays PADANARAM 10.00-10.20 3 Oct DYKEHEAD: TULLOCH WYND 11.10-11.30 10 Oct NEWTYLE: CHURCH ST 10.45-11.50 17 Oct KINGOLDRUM 12.00-12.30 24 Oct NEWTYLE: SOUTH ST 11.55-12.15 31 Oct AIRLIE HALL 13.30-13.50 7 Nov NEWTYLE: KINPURNEY GDNS 12.20-12.40 14 Nov WESTMUIR: POST OFFICE 14.00-14.30 21 Nov EASSIE HALL 13.25-13.40 28 Nov WESTMUIR: DAVID LAWSON GDNS 14.45-15.05 5 Dec GLAMIS: STRATHMORE ROAD 13.55-14.10 12 Dec GLAMIS: SQUARE 15.15-15.35 19 Dec GLAMIS: by SCHOOL 14.15-15.00 26 Dec Holiday CHARLESTON -

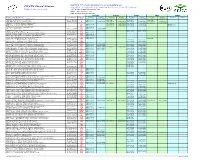

PCHS Herd Status

Qualifying = The herd has passed the current qualifying test PCHS Herd Status Accredited = Accreditation of freedom from the disease to CHeCS standards Published - 30/09/2021 06:00:50 VMF = Vaccinated Monitored Free MMF = Milk Monitored Free LMF = Lepto Monitored Free Johnes Lepto BVD IBR NEO Name and Address Telephone Breed Status Since Status Since Status Since Status Since Status Since Cade, PA - Paddock Farm, Taylors Lane SM Risk level 1 06/02/2020 Accredited 11/02/2019 Accredited 11/02/2019 Accredited 11/02/2019 Carnegie, Kevin - Menmuir, Brechin 01356 648 648 Risk level 2 Qual 1st Qual 1st Qual 1st Cork, HM - The Hayes, County Lane 07751138438 H Risk level 1 22/03/2017 Accredited 24/03/2016 Accredited 24/03/2016 Accredited 24/03/2016 Haggarty, J - Sulham Estate, Sulham Farm Accredited 14/04/2020 Accredited 14/04/2020 Accredited 14/04/2020 Hopkin, G - Cefn Coed Farm, Llanharry AA Risk level 4 Accredited 23/06/2020 Accredited 23/06/2020 Risk level 3 Hopkin, G - Cefn Coed Farm, Llanharry WB Risk level 4 Accredited 23/06/2020 Accredited 23/06/2020 Risk level 3 Johnson, N - Cae Bach, Pantglas Farm HE Risk level 2 Pirie, G - 22 Howe Street 0131 2264800 AA Risk level 1 28/04/2015 Rowlands a'I Fab, TE - Tyddyn Du, Cwm Hafodoer 01341422502 WB Risk level 1 28/01/2005 Accredited 24/02/2020 Spiby, CJ - Chalder Farm 01243 641219 HO Accredited 08/12/2020 Sullivan, Robert - Raby Home Farm, C/o 3 Office Square 01913039541 AAX Risk level 2 Sullivan, Robert - Raby Home Farm, C/o 3 Office Square 01913039541 LUX Risk level 2 Taylor, BP - Old House -

Arbroath Abbey Final Report March 2019

Arbroath Abbey Final Report March 2019 Richard Oram Victoria Hodgson 0 Contents Preface 2 Introduction 3-4 Foundation 5-6 Tironensian Identity 6-8 The Site 8-11 Grants of Materials 11-13 The Abbey Church 13-18 The Cloister 18-23 Gatehouse and Regality Court 23-25 Precinct and Burgh Property 25-29 Harbour and Custom Rights 29-30 Water Supply 30-33 Milling 33-34 The Almshouse or Almonry 34-40 Lay Religiosity 40-43 Material Culture of Burial 44-47 Liturgical Life 47-50 Post-Reformation Significance of the Site 50-52 Conclusions 53-54 Bibliography 55-60 Appendices 61-64 1 Preface This report focuses on the abbey precinct at Arbroath and its immediately adjacent appendages in and around the burgh of Arbroath, as evidenced from the documentary record. It is not a history of the abbey and does not attempt to provide a narrative of its institutional development, its place in Scottish history, or of the men who led and directed its operations from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. There is a rich historical narrative embedded in the surviving record but the short period of research upon which this document reports did not permit the writing of a full historical account. While the physical structure that is the abbey lies at the heart of the following account, it does not offer an architectural analysis of the surviving remains but it does interpret the remains where the documentary record permits parts of the fabric or elements of the complex to be identified. This focus on the abbey precinct has produced some significant evidence for the daily life of the community over the four centuries of its corporate existence, with detail recovered for ritual and burial in the abbey church, routines in the cloister, through to the process of supplying the convent with its food, drink and clothing. -

Mobile Library Timetable

MOBILE LIBRARY TIMETABLE 2021 Week 1 - Van 1 - Isla Week 2 - Van 1 – Isla Beginning Monday 26th April 2021 Beginning Monday 3rd May 2021 MONDAY – APR 26 | MAY 10, 24 | JUN 7, 21 | JUL 5, MONDAY – MAY 3 (public holiday), 17, 31 | JUN 14, 28 19 | AUG 2, 16, 30 | SEP 13, 27 | JUL 12, 26 | AUG 9, 23 | SEP 6, 20 10:25-10:55 Wellbank (by school) 10:00-10:30 Inverarity (by school) 11:00-11:20 Wellbank (Gagiebank) 10:45-11:15 Tealing (by school) 11:35-12:05 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 11:30-12:00 Strathmartine (by school) 12:40-12:55 Newbigging (Templehall Gardens) 12:50-13:20 Craigton of Monikie (by school) 13:00 -13:20 Newbigging (by School) 13:25-13:50 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 13:35-13:55 Forbes of Kingennie (Car Park Area) 14:00-14:25 Balumbie (Silver Birch Drive) 14:25 -14:45 Strathmartine (Ashton Terrace) 14:30-14:55 Balumbie (Poplar Drive) 15:10-15:30 Ballumbie (Oak Loan) 15:10-15:30 Murroes Hall 15:35-15:55 Ballumbie (Elm Rise) 15:40-16:00 Inveraldie Hall TUESDAY – APR 27 | MAY 11, 25 | JUN 8, 22 | JUL 6, TUESDAY – MAY 4, 18 | JUN 1, 15, 29 | JUL 13, 27 | 20 | AUG 3, 17, 31 | SEP 14, 28 AUG 10, 24 | SEP 7, 21 10:10-10:30 Guthrie (By Church) 10:00 -10:25 Kingsmuir (Dunnichen Road) 10:35-11:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) 10:50-11:25 Arbirlot (by School) 11:20-12:00 Dunnichen (By Church) 11:30-11:45 Balmirmer 11:55-12:20 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 12:10-12:30 Bowriefauld 13:30-13:50 Muirdrum 13:30-14:00 Barry Downs (Caravan Park) 14:00-14:30 Letham (Jubilee Court) 14:20-14:50 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 14:35-15:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) -

Solar Pv West Balmirmer Farm

SOLAR PV WEST BALMIRMER FARM LOCATION West Balmirmer Farm, Angus, Scotland SYSTEM SIZE 50kWp EXPECTED ANNUAL GENERATION 43,100kWh West Balmirmer, owned and operated by the Fairlie family, is a mixed arable and livestock farm near Arbroath. With renewable energy installations at their other farms, the Fairlies were keen to invest in a suitable technology at West Balmirmer to further reduce the carbon impact of the business and cut their electricity spend at the site. After Locogen had installed and commissioned a 500kW wind turbine for Locogen provided a turnkey service for the project, completing all the the Fairlies at Pickerton Farm, and achieved planning consent for a similar works from the initial energy yield assessments through to the design and turbine at Stotfaulds Farm, the family approached Locogen to advise on installation of the solar array, before finally commissioning the system and the most suitable technology at West Balmirmer. accrediting it to receive FiT payments. The high energy use at the farm coupled with the southerly orientation of The system features 200 x REC 250W panels and is connected to the grid roof space lent itself well to a solar installation, providing a low-risk via SMA inverters. Around 90% of the electricity generated is used onsite, opportunity to secure a long-term income from the Feed-in Tariff (FiT) creating a significant saving for the business. whilst further boosting the farm’s environmental performance. “I have worked with Locogen on various renewable energy projects since I started looking into options across the farming business in 2012. The solar installation at West Balmirmer is a welcome addition to the business, and has been installed in a timely manner, with no disruption to the farming operations.” David Fairlie, Owner Locogen – Edinburgh Office Mitchell House, 5 Mitchell Street, Edinburgh EH6 7BD Tel. -

Angus Licensing Board 9 August

AGENDA ITEM NO 9 REPORT NO LB49/18 ANGUS LICENSING BOARD – 9 AUGUST 2018 OCCASIONAL LICENCES – DELEGATED APPROVALS REPORT BY CLERK TO THE BOARD ABSTRACT The purpose of this report is to advise members of applications for occasional licences under the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005 which have been granted by the Clerk in accordance with the Scheme of Delegation appended to the Boards Statement of Licensing Policy. 1. RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Board note the applications for occasional licences granted under delegated authority as detailed in the attached Appendix. 2. BACKGROUND In terms of the Scheme of Delegation appended to the Boards Statement of Licensing Policy, the Clerk to the Board is authorised to grant applications for occasional licences under the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005 where no objections or representations have been received, nor a notice recommending refusal from the Divisional Commander, Tayside Division of Police Scotland or any report from the Licensing Standards Officer recommending refusal where the application relates to hours within Section 6 of the Board’s policy. Attached as an Appendix is a list of applications for extended hours granted under delegated authority during the period 25 August 2018 to 20 July 2018. 3. FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS There are no financial implications arising from this report. NOTE: No background papers were relied on to a material extent in preparing the above report. REPORT AUTHOR: Dawn Smeaton, Licensing and Litigation Assistant E-MAIL: [email protected] APPENDIX -

Forfarshire Directory for 1887-8

THE LARGEST Glass A China Rooms IN THE NORTH OF SCOTLAND. Established 1811. Beg to solicit inspection of their Choice and Varied Stock of GLASS, 6HINA,& EARTHENWARE One of the Largest in the Country, And arranged so as to give every facility for inspection. Useful Goods from the plainest serviceable quality to the hand- somest and best ; Fancy and Ornamental, in all the newest Avares and styles. From their CONNECTION OF UPWARDS 'OF HALF-A- CENTUPvY with all the leading Manufacturers, and their immense turn-over, W. F. & S. are enabled to give exceptional advantages as to quality and price. WEDDING & COMPLIMENTARY GIFTS—Special Selection. FAIRY LAMPS AND LIGHTS always in Stock. Wholesale and Retail. SPECIAL RATES FOR HOTELS, &c. 17, 19, and 21 CASTLE STREET, DUNDEE. Shut on Saturdays at 3 p.m. National Library of Scotland llllllllllllllllllllllillllillilillllllll *B000262208* Established 1850. CHARLES SMITH & SON, Cabinetmakers, Joiners, & Packing-case Makers, HOUSE AGENTS AND VALUATORS. FUNERAL UNDERTAKERS. | 12 QUEEN STREET, DUNDEE. ESTABLISHED 1875. Strong BALFOUR'S Fragrant /- Is now extensively used . in Town and Country, and is giving immense satisfac- tion to all classes. It possesses Strength, Flayqur, and Quality, and is in every respect a very desirable and refreshing Tea. Send for Sample and compare. Anah/sfs Reporf sent wiiji gamples. 1/10 per lb. in 5 or 10 lb. parcels. D. BALFOUR. Wholesale and Retail Dealer, AND TEAS, COFFEES, WINES, &c, 135 and 127 HAWKHILL, DUNDEE. Cheap Good Bran<sh-335J HILLTOWN. Pianofortes, Organs, and Barmoniums By all the most Celebrated Makers, FOR SAXiS o;xl xxxixi.es, And on the Three Years'JSystem. -

Global Marine Report 2018

SCOTTISH FUTURES TRUST INTERNATIONAL FIBRE OPTIC CABLE LANDING DESK TOP STUDY 2682-GMSL-G-RD-0001_01 REVISION DATE ISSUE DETAILS PREPARED CHECKED APPROVED 01 01/11/2018 Draft issue MW, AR, JW SW MW 02 14/11/2018 Final issue MW, AR BP MW Document Filename: 2682-GMSL-G-RD-0001 Version Number: 02 Date: November 2018 AUTHOR OF REVISION SECTION PAGES BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF CHANGES CHANGE Additional information on the fishing vessel 7.3.3 81 AR anchorage offshore of Port William Harbour. 7.8.1 89 Inserted note regarding planned cables. MW Additional content added in the Scottish permit 9.3.1 109 AR summary. 10.1 120 Updated RPL revisions. MW 02 An existing duct that is 150mm in diameter is 13.2 154 available on the east of Bottle Hole Bridge added to AR site visit report 13.8 160 Model Option and Licence Agreements included as AR 13.9 162 additional appendices. 13.10 162 Updated RPL revisions. MW Page 2 of 164 Document Filename: 2682-GMSL-G-RD-0001 Version Number: 02 Date: November 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 12 1.1 Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Route Overview ........................................................................................................................ 13 1.3 Executive Summary Table ........................................................................................................ 14 2.0 -

SCRI Annual Report 1994

Scottish Crop Research Institute Annual Report 1994 Contents on page 4 Governing Body Chairman J.L.Millar, C.B.E., C.A. Professor Heather M. Dick, M.D., F.R.C.P. Glas., F.R.C.Path., F.I.Biol., F.R.S.E. J.B. Forrest, F.R.Ag.S. J.E. Godfrey Professor J.D. Hayes, B.Sc., M.S., Ph.D., F.I.Biol. J.A. Inverarity, O.B.E. A.M. Jacobsen Professor D.L. Lee, B.Sc., Ph.D., C.Biol., F.I.Biol., F.R.S.A. A. Logan A.N. MacCallum, B.Sc.. (w.e.f. 1/4/95) Professor T.A. Mansfield, Ph.D., F.I.Biol., F.R.S. Professor J.W. Parsons, B.Sc., Ph.D., F.I.Biol. Professor J.A. Raven, M.A., Ph.D., F.R.S.E., F.R.S. G. Rennie Professor A.R. Slabas, B.Sc., D.Phil. (w.e.f. 1/4/95) L.M. Thomson T.P.M. Thomson Accountants : KPMG, Royal Exchange, Dundee. Solicitors : Dundas and Wilson C.S., Saltire Court, 20 Castle Terrace, Edinburgh. Banking : Bank of Scotland, 11-19 Reform Street, Dundee. Patent Agents : Murgitroyd & Co, 373 Scotland Street, Glasgow. Supervisory Medical Officers : Dr Ann Simpson & Dr S Mitchell, Occupational Health Service, Panmure House, 4 Dudhope Terrace, Dundee. Occupational Health and Safety Agency : Mr J.R. Brownlie, 18-20 Hill Street, Edinburgh. Scottish Crop Research Institute Invergowrie, Dundee DD2 5DA, Scotland, UK. A charitable company (No. SC006662) limited by guarantee No. 29367 (Scotland) and registered at the above address. -

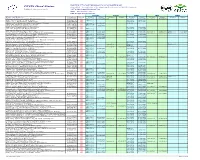

PCHS Herd Status

Qualifying = The herd has passed the current qualifying test PCHS Herd Status Accredited = Accreditation of freedom from the disease to CHeCS standards Published - 30/09/2021 06:01:13 VMF = Vaccinated Monitored Free MMF = Milk Monitored Free LMF = Lepto Monitored Free Johnes Lepto BVD IBR NEO Name and Address Telephone Breed Status Since Status Since Status Since Status Since Status Since Acton, LA - Bradley Farm, Bardon Mill, Northumberland 01434344261 AA Risk level 1 14/01/2008 LMF Accredited 18/01/2010 Accredited 16/02/2016 Adam, RM - Newhouse of Glamis, Angus 01307840678 AA Risk level 3 Accredited 24/03/2005 Adams, A & J - Eastfield Farm, Aberdeenshire 01339 755395 AA Accredited 10/11/2011 Addison, R C S - Greystone House, Kings Meaburn, Cumbria 01931714663 AA Risk level 1 24/02/2021 BVD VMF Agnew, WJ - Balwherrie, Dumfries & Galloway 01776 854242 AA Risk level 4 Alford, M - Foxhill Farm, Blackbourgh, Devon 01884 849369 AA Risk level 1 10/09/2013 Allan, W & D - Leaderfoot Farm, Roxburghshire 01896822298 AA Accredited 12/12/2013 Allen, WD - Humbleheugh, Northumberland 01665579274 AA Risk level 2 Accredited 12/01/2015 Anderson, S - Stouslie Farm, Roxburghshire 01450 371340 AA Risk level 3 Accredited 14/12/2016 Andrews, DW - Warson Barton Farm, Coryton, Devon 01822 820402 AA Risk level 1 15/01/2021 Accredited 20/02/2017 Accredited 28/09/2016 Risk level 1 21/12/2020 Anema, JD & NJ - Old Hall Farm, Dereham Road, Westfield, Norfolk 01362695732 AA Risk level 1 06/03/2012 Accredited 14/02/2014 Accredited 06/03/2012 Risk level 1 11/01/2021 -

306 the Edinburgh Gazette, June 11, 1954

306 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, JUNE 11, 1954 STATEMENT showing the QUANTITIES SOLD and AVERAGE ROYAL BURGH OF DUMBARTON PRICES OF BRITISH CORN per cwt of 112 Imperial Ib. computed from returns received by the MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT (SCOTLAND) ACT, 1947 AGRICULTURE AND FISHERIES in the week ended 5th EXTENSION OF BURGH June 1954, pursuant to the Corn Returns Act, 1882, INTIMATION is hereby given that the Provost, Magis- the Corn Sales Act, 1921, and the Agriculture (Miscel- trates, and Councillors of the Royal Burgh of Dumbarton laneous Provisions) Act, 1943. have presented a Petition to the Sheriff of Stirling, Dum- barton, and Clackmannan, at Dumbarton, craving the British Corn Quantities Sold Average Price per Cwt. extension of the boundaries of the said Burgh to include within the Burgh land extending to 96.517 acres forming part of the lands of Aitkenbar and Loaning Head lying cwt. s. d. to the north-east of the Burgh, and that the Sheriff-Principal VHEAT 470,554 33 11 has issued the following Interlocutor: — PARLEY 54,078 25 3 OATS 31,870 22 7 "Dumbarton 1th June 1954.—The Sheriff, having con- " sidered the foregoing Petition, appoints the Pursuers to " advertise the import of the Petition and of this Deliverance NOTE.—The above statement is based on returns received " once in each of the Edinburgh Gazette and in the Glasgow from 174 prescribed towns in England and Wales in the " Herald and the Lennox Herald newspapers, and also by week ended 5th June 1954. The prices represent the "handbills to be posted within the Burgh of Dumbarton average for all sales at these towns, and include " and within the area proposed to be included within the transactions between growers and merchants, and " revised and extended boundaries of said Burgh; further, transactions between merchants, during the week ended "appoints the Pursuers to serve a copy of the Petition 29th May 1954.