SCRI Annual Report 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PCN Guidelines, and Potato Cyst Nematodes (Globodera Rostochiensis Or Globodera Pallida) Were Not Detected.”

Canada and United States Guidelines on Surveillance and Phytosanitary Actions for the Potato Cyst Nematodes Globodera rostochiensis and Globodera pallida 7 May 2014 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 2. Rationale for phytosanitary actions ........................................................................................................................3 3. Soil sampling and laboratory analysis procedures .................................................................................................4 4. Phytosanitary measures ........................................................................................................................................4 5. Regulated articles .................................................................................................................................................5 6. National PCN detection survey..............................................................................................................................6 7. Pest-free places of production or pest-free production sites within regulated areas ...............................................6 8. Phytosanitary certification of seed potatoes ..........................................................................................................7 9. Releasing land from regulatory control ..................................................................................................................8 -

Download Article (PDF)

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 240 Stlldies on plant and soil Nematodes associated with crops of economic importance in Gujarat QAISER H. BAQRI PADMA BOHRA ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 240 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Studies on plant and soil Nematodes associated with crops of economic importance in Gujarat. QAISER H. BAQRI AND PADMA BOHRA Desert Regional Station, Zoological Survey of India, Pali Road, Jhalan1and, Jodhpur - 342 005 Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata. Zoological Survey of India Kolkata CITATION Dr. BAQRI Qaiser H. & Dr. BOHRA Padma., 2005. Studies on Plant and Soil Nematodes Associated with Crops of Economic Importance in Gujarat of the Zoological Survey of India, : Rec. zool. Surv. India, Occasional Paper No. 240 : 1-48 (Published by the Director, Zoo I. Surv. India) Published : July, 2005 ISBN 81-8171-076-2 © Govt. of India, 2005 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, el~ctronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in an form of binding or cover other than that in which, it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. -

SCRI Annual Report 1994

Scottish Crop Research Institute Annual Report 1994 Contents on page 4 Governing Body Chairman J.L.Millar, C.B.E., C.A. Professor Heather M. Dick, M.D., F.R.C.P. Glas., F.R.C.Path., F.I.Biol., F.R.S.E. J.B. Forrest, F.R.Ag.S. J.E. Godfrey Professor J.D. Hayes, B.Sc., M.S., Ph.D., F.I.Biol. J.A. Inverarity, O.B.E. A.M. Jacobsen Professor D.L. Lee, B.Sc., Ph.D., C.Biol., F.I.Biol., F.R.S.A. A. Logan A.N. MacCallum, B.Sc.. (w.e.f. 1/4/95) Professor T.A. Mansfield, Ph.D., F.I.Biol., F.R.S. Professor J.W. Parsons, B.Sc., Ph.D., F.I.Biol. Professor J.A. Raven, M.A., Ph.D., F.R.S.E., F.R.S. G. Rennie Professor A.R. Slabas, B.Sc., D.Phil. (w.e.f. 1/4/95) L.M. Thomson T.P.M. Thomson Accountants : KPMG, Royal Exchange, Dundee. Solicitors : Dundas and Wilson C.S., Saltire Court, 20 Castle Terrace, Edinburgh. Banking : Bank of Scotland, 11-19 Reform Street, Dundee. Patent Agents : Murgitroyd & Co, 373 Scotland Street, Glasgow. Supervisory Medical Officers : Dr Ann Simpson & Dr S Mitchell, Occupational Health Service, Panmure House, 4 Dudhope Terrace, Dundee. Occupational Health and Safety Agency : Mr J.R. Brownlie, 18-20 Hill Street, Edinburgh. Scottish Crop Research Institute Invergowrie, Dundee DD2 5DA, Scotland, UK. A charitable company (No. SC006662) limited by guarantee No. 29367 (Scotland) and registered at the above address. -

Mobile Library Route Timetable

MOBILE LIBRARY SERVICE JOIN US AND BEGIN YOUR JOURNEY Week 1 (begins Monday 2nd Oct 2017) VAN 2 Week 2 (begins Monday 9th Oct 2017) VAN 1 Day/Date Location Time Day/Date Location Time Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 2 Oct LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 9 Oct LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 16 Oct ABERLEMNO 11.15-11.45 23 Oct TANNADICE 11.20-11.40 30 Oct LITTLE BRECHIN 12.10-12.30 6 Nov MEMUS 11.55-12.20 13 Nov EDZELL: by PRIMARY SCHOOL 13.20-14.10 20 Nov NORANSIDE 13.05-13.25 27 Nov EDZELL MEMORIAL HALL 14:15-14:45 4 Dec KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 13.45-14.05 11 Dec KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 15.15-15.45 18 Dec INCHBARE 14.20-14.40 25 Dec Holiday NORANSIDE 16.00-16.30 1st Jan Holiday EDZELL: BY PS 14.55-15.45 8 Jan MEMUS 16.40-17.05 EDZELL: INGLIS COURT 15.55-16.20 TANNADICE 17.15-17.45 EDZELL: CHURCH ST 16.30-16.45 WATERSTON ROAD 18.00-18.20 EDZELL: MEMORIAL HALL 16.50-17.20 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.40-19.00 LITTLE BRECHIN 17.55-18.15 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.35-19.00 Tuesdays CORTACHY: by PS 10.15-11.00 Tuesdays PADANARAM 10.00-10.20 3 Oct DYKEHEAD: TULLOCH WYND 11.10-11.30 10 Oct NEWTYLE: CHURCH ST 10.45-11.50 17 Oct KINGOLDRUM 12.00-12.30 24 Oct NEWTYLE: SOUTH ST 11.55-12.15 31 Oct AIRLIE HALL 13.30-13.50 7 Nov NEWTYLE: KINPURNEY GDNS 12.20-12.40 14 Nov WESTMUIR: POST OFFICE 14.00-14.30 21 Nov EASSIE HALL 13.25-13.40 28 Nov WESTMUIR: DAVID LAWSON GDNS 14.45-15.05 5 Dec GLAMIS: STRATHMORE ROAD 13.55-14.10 12 Dec GLAMIS: SQUARE 15.15-15.35 19 Dec GLAMIS: by SCHOOL 14.15-15.00 26 Dec Holiday CHARLESTON -

Molecular Characterization of Canadian Populations of Potato Cyst

Can. J. Plant Pathol. (2010), 32(2): 252–263 Soilborne pathogens/Agents pathogènes telluriques MolecularTCJP characterization of Canadian populations of potato cyst nematodes, Globodera rostochiensis and G. pallida using ribosomal nuclear RNA and cytochrome b genes M.Potato cyst nematodes MADANI1, S. A. SUBBOTIN2, L. J. WARD1, X. LI1 AND S. H. DE BOER1 1Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Charlottetown Laboratory, 93 Mount Edward Road, Charlottetown, PE C1A 5T1, Canada 2Plant Pest Diagnostics Center, California Department of Food and Agriculture, 3294 Meadowview Road, Sacramento, CA 95832-1448, USA (Accepted 10 January 2010) Abstract: The mitochondrial cytochrome b gene (cytb), the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) of the rRNA gene and D2-D3 expansion segments of the 28S rRNA gene were amplified, sequenced and used to characterize several populations of potato cyst nematodes, Globodera pallida and G. rostochiensis, collected from different areas in Canada. Diagnostic PCR-ITS-RFLP profiles with three restriction enzymes are provided for identification of both species. Sequences of ITS rRNA and cytb genes were compared with those in Genbank of other potato cyst nematode populations originating from Europe, South America, USA, Australia and New Zealand. The ITS rRNA sequences of Canadian G. rostochiensis were similar to those of all previously sequenced populations of this species. Sequence divergence of ITS rRNA for G. rostochiensis varied from 0 to 1.6%, whereas for G. pallida sequence divergence among populations reached 1.95%. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of cytb and ITS rRNA genes using Bayesian inference revealed that Canadian G. pallida is almost identical to European and USA populations and formed a large clade with all these populations on the phylogenetic trees. -

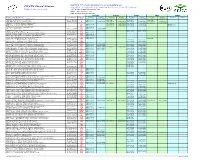

PCHS Herd Status

Qualifying = The herd has passed the current qualifying test PCHS Herd Status Accredited = Accreditation of freedom from the disease to CHeCS standards Published - 30/09/2021 06:00:50 VMF = Vaccinated Monitored Free MMF = Milk Monitored Free LMF = Lepto Monitored Free Johnes Lepto BVD IBR NEO Name and Address Telephone Breed Status Since Status Since Status Since Status Since Status Since Cade, PA - Paddock Farm, Taylors Lane SM Risk level 1 06/02/2020 Accredited 11/02/2019 Accredited 11/02/2019 Accredited 11/02/2019 Carnegie, Kevin - Menmuir, Brechin 01356 648 648 Risk level 2 Qual 1st Qual 1st Qual 1st Cork, HM - The Hayes, County Lane 07751138438 H Risk level 1 22/03/2017 Accredited 24/03/2016 Accredited 24/03/2016 Accredited 24/03/2016 Haggarty, J - Sulham Estate, Sulham Farm Accredited 14/04/2020 Accredited 14/04/2020 Accredited 14/04/2020 Hopkin, G - Cefn Coed Farm, Llanharry AA Risk level 4 Accredited 23/06/2020 Accredited 23/06/2020 Risk level 3 Hopkin, G - Cefn Coed Farm, Llanharry WB Risk level 4 Accredited 23/06/2020 Accredited 23/06/2020 Risk level 3 Johnson, N - Cae Bach, Pantglas Farm HE Risk level 2 Pirie, G - 22 Howe Street 0131 2264800 AA Risk level 1 28/04/2015 Rowlands a'I Fab, TE - Tyddyn Du, Cwm Hafodoer 01341422502 WB Risk level 1 28/01/2005 Accredited 24/02/2020 Spiby, CJ - Chalder Farm 01243 641219 HO Accredited 08/12/2020 Sullivan, Robert - Raby Home Farm, C/o 3 Office Square 01913039541 AAX Risk level 2 Sullivan, Robert - Raby Home Farm, C/o 3 Office Square 01913039541 LUX Risk level 2 Taylor, BP - Old House -

Globodera Alliance Newsletter

September 2017, Issue 4 Globodera Alliance Newsletter Potato Cyst Nematodes Around the World: All you wanted to know about their distribution and evolution history Eric Grenier and Benjamin Mimee PCN Distribution Inside this issue: Potato cyst nematodes (PCN) are among the most highly specialized and success- PCN distribution 1 ful plant parasitic nematodes. They rank 2nd in the 'top 10' list of the plant para- Globodera diversity 2 sitic nematodes based on their scientific and economic importance. Like their G. rostochiensis origins 2 main host crop, potato, PCN have spread to almost all parts of the world, initially in soil adhering to tubers from infested land but also by any other means that G. pallida origins 3 transport soil containing cysts. Their pathways of distribution are still a matter of PCN in Idaho 3 speculation but PCN are believed to have originated in the Andean region of Peru Phylogeographic map of and Bolivia. Today, PCN occur on all continents, in temperate, tropical or south- G. pallida 4 ern tropical zones, both at sea level and at higher altitudes. Results suggest that About GLOBAL Project 5 Europe is a secondary distribution center, but one exception may be transport of PCN Field Tour 5 cysts from Peru to Japan in contaminated guano sacks. Upcoming Events 5 Nematodes - Globodera Alliance Newsletter September 2017, Issue 4 Page 2 Overview of Globodera diversity Potato cyst nematodes belong to the genus Globodera which comprises of species, with the exception of G. zeland- ica, parasitic to plants belonging to either the Solanaceae or Compositae. At least eight Globodera species parasitiz- ing Solanaceae have been identified. -

Globodera Rostochiensis (Woll.) Heteroderidae)

Agric. Sei. Finl. 1 (1992) ( ), Globodera rostochiensis (Woll.) Behrens Tylenchida, Heteroderidae the only potato cyst nematode species found in Finland Jari Heikkilä and Kari Tiilikkala Heikkilä, J. & Tiilikkala, K. 1992. Globodera rostochiensis (Woll.) Behrens (Tylen- chida, Heteroderidae), the only potato cyst nematode species found in Finland. Agric. Sei. Finl. 1; 519- 525. (Univ. Helsinki, Dept. Zoology, SF-00100 Helsinki, Agric. Res. Centre ofFinland, Inst. PI. Protect., SF-31600 Jokioinen, Finland.) About 10 000 soil samples, 519 thereof infected with potato cyst nematode (PCN), were studied during 1984-1988. Cysts from infected samples were tested by isoelectric focusing to identify PCN species. All the infected samples were also tested with Hl-resistant (Satuma) and susceptible (Bintje) potato cultivars to separate resistance breaking populations. Cysts from the roots of Satuma were tested by two-dimensional electrophoresis. The potato seed production area in Finland was found to be free ofPCN of any kind. In other parts ofFinland all tested samples revealed G. rostochiensis banding pattern, but no G. pallida was found. Except for the most common pathotype Rol-Ro4, we only found Ro2. Key words: potato cyst nematode, PCN, Globodera rostochiensis, Globoderapallida, isoelectric focusing, two-dimensional electrophoresis Introduction the early 1970 s (Sarakoski 1976a). Since the be- ginning ofthe 19705,PCN has been the most harm- In Finland, potatoes are grown commercially on ful pest ofpotatoes in Finland. about 41 000 hectares. The cultivated area extends Magnusson (1987) and Tiilikkala (1987, from the southern coast (60° 00’N) up to the north 1991) have studied the biological and physical fac- (69° 00’N). -

Arbroath Abbey Final Report March 2019

Arbroath Abbey Final Report March 2019 Richard Oram Victoria Hodgson 0 Contents Preface 2 Introduction 3-4 Foundation 5-6 Tironensian Identity 6-8 The Site 8-11 Grants of Materials 11-13 The Abbey Church 13-18 The Cloister 18-23 Gatehouse and Regality Court 23-25 Precinct and Burgh Property 25-29 Harbour and Custom Rights 29-30 Water Supply 30-33 Milling 33-34 The Almshouse or Almonry 34-40 Lay Religiosity 40-43 Material Culture of Burial 44-47 Liturgical Life 47-50 Post-Reformation Significance of the Site 50-52 Conclusions 53-54 Bibliography 55-60 Appendices 61-64 1 Preface This report focuses on the abbey precinct at Arbroath and its immediately adjacent appendages in and around the burgh of Arbroath, as evidenced from the documentary record. It is not a history of the abbey and does not attempt to provide a narrative of its institutional development, its place in Scottish history, or of the men who led and directed its operations from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. There is a rich historical narrative embedded in the surviving record but the short period of research upon which this document reports did not permit the writing of a full historical account. While the physical structure that is the abbey lies at the heart of the following account, it does not offer an architectural analysis of the surviving remains but it does interpret the remains where the documentary record permits parts of the fabric or elements of the complex to be identified. This focus on the abbey precinct has produced some significant evidence for the daily life of the community over the four centuries of its corporate existence, with detail recovered for ritual and burial in the abbey church, routines in the cloister, through to the process of supplying the convent with its food, drink and clothing. -

Hatch and Reproduction of Globodera Tabacum Tabacum in Response to Tobacco, Tomato, Or Black Nightshade J

Journal of Nematology 27(3):382-386. 1995. © The Society of Nematologists 1995. Hatch and Reproduction of Globodera tabacum tabacum in Response to Tobacco, Tomato, or Black Nightshade J. A. LAMONDIA 1 Abstract: The effects of broadleaf tobacco, tomato, and black nightshade on juvenile hatch and reproduction of Globodera tabacum tabacum were determined in laboratory and greenhouse experi- ments. Root exudates from nightshade stimulated greater egg hatch than those from either 'Rutgers' tomato or '86-4' tobacco. Hatch was greater at higher proportions of root exudates for all three plant species. Root exudates from plants greater than 3 weeks old stimulated more hatch than younger plants. No regression relationships existed between plant age and nematode batch. In other exper- iments, hatch from eggs in cysts was higher for tomato and nightshade after 10 weeks in greenhouse pots compared to tobacco and bare soil. Numbers of second-stage juveniles in eggs in cysts produced from a previous generation on the same host were highest on nightshade and less on tomato and tobacco. Cysts of variable age recovered from field soil had increased hatch in both root exudates or water compared to recently produced cysts from plants in growth chambers. Globodera t. tabacum may be subject to both host and environmentally mediated diapause. Key words: hatch stimulation, Nicotiana tabacum, Lycopersicon esculentum, nematode, root exudates, Solanum nigrum, tobacco cyst nematode. The tobacco cyst nematode, Globodera experiments. G. t. tabacum, however, can tabacum tabacum (Lownsbery and Lowns- persist in soil for many years in the absence bery) Behrens, is an important parasite of of a host (1), suggesting some form of dor- shade (9,13) and broadleaf (11) tobacco in mancy with survival value. -

Mobile Library Timetable

MOBILE LIBRARY TIMETABLE 2021 Week 1 - Van 1 - Isla Week 2 - Van 1 – Isla Beginning Monday 26th April 2021 Beginning Monday 3rd May 2021 MONDAY – APR 26 | MAY 10, 24 | JUN 7, 21 | JUL 5, MONDAY – MAY 3 (public holiday), 17, 31 | JUN 14, 28 19 | AUG 2, 16, 30 | SEP 13, 27 | JUL 12, 26 | AUG 9, 23 | SEP 6, 20 10:25-10:55 Wellbank (by school) 10:00-10:30 Inverarity (by school) 11:00-11:20 Wellbank (Gagiebank) 10:45-11:15 Tealing (by school) 11:35-12:05 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 11:30-12:00 Strathmartine (by school) 12:40-12:55 Newbigging (Templehall Gardens) 12:50-13:20 Craigton of Monikie (by school) 13:00 -13:20 Newbigging (by School) 13:25-13:50 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 13:35-13:55 Forbes of Kingennie (Car Park Area) 14:00-14:25 Balumbie (Silver Birch Drive) 14:25 -14:45 Strathmartine (Ashton Terrace) 14:30-14:55 Balumbie (Poplar Drive) 15:10-15:30 Ballumbie (Oak Loan) 15:10-15:30 Murroes Hall 15:35-15:55 Ballumbie (Elm Rise) 15:40-16:00 Inveraldie Hall TUESDAY – APR 27 | MAY 11, 25 | JUN 8, 22 | JUL 6, TUESDAY – MAY 4, 18 | JUN 1, 15, 29 | JUL 13, 27 | 20 | AUG 3, 17, 31 | SEP 14, 28 AUG 10, 24 | SEP 7, 21 10:10-10:30 Guthrie (By Church) 10:00 -10:25 Kingsmuir (Dunnichen Road) 10:35-11:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) 10:50-11:25 Arbirlot (by School) 11:20-12:00 Dunnichen (By Church) 11:30-11:45 Balmirmer 11:55-12:20 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 12:10-12:30 Bowriefauld 13:30-13:50 Muirdrum 13:30-14:00 Barry Downs (Caravan Park) 14:00-14:30 Letham (Jubilee Court) 14:20-14:50 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 14:35-15:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) -

SCRI Annual Report 1996/1997

Scottish Crop Research Institute Annual Report 1996/97 Contents on page 4 Governing Body Chairman A.N. MacCallum, B.Sc., F.D.I.C. (w.e.f. 1-4-97) J.L.Millar, C.B.E., C.A. (Retired 1-4-97) A.C. Bain (w.e.f. 1-4-97) Professor R.J. Cogdell, B.Sc., Ph.D., F.R.S.E. (w.e.f. 1-4-97) Professor Heather M. Dick, M.D., F.R.C.P. Glas., F.R.C.Path., C.Biol., F.I.Biol., F.R.S.E. J.M. Drysdale (w.e.f. 1-4-97) J.B. Forrest, F.R.Ag.S. J.E. Godfrey, B.Sc., A.R.Ag.S. Professor J.D. Hayes, B.Sc., M.S., Ph.D., C.Biol., F.I.Biol. (Retired 1-4-97) K. Hopkins, F.C.A. (w.e.f. 1-4-97) J.A. Inverarity, O.B.E., C.A., F.R.Ag.S., F.R.S.A. (Retired 1-4-97) A.M. Jacobsen, B.Sc.Agric. (Retired 1-4-97) Professor D.L. Lee, B.Sc., Ph.D., C.Biol., F.I.Biol., F.Z.S., F.R.S.A. A. Logan, S.D.A., N.D.A., F.I.Hort. (Retired 1-4-97) Professor T.A. Mansfield, Ph.D., C.Biol., F.I.Biol., F.R.S. (Retired 1-4-97) Professor J.A. Raven, M.A., Ph.D., Ph.D.h.c., F.R.S.E., F.R.S. (Retired 1-4-97) G. Rennie, O.N.D.Agric.