Food in World History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A STUDYGUIDE by Robert Lewis

A STUDYGUIDE BY ROBERT LEWIS www.metromagazine.com.au www.theeducationshop.com.au McLibel (Franny Armstrong, 2005) is an 85-minute documentary film about the attempt by McDonald’s to stop the distribution of a pamphlet that they claimed defamed them. wo of the distributors of the settlement negotiations. Even spies. BEFORE WATCHING THE pamphlet, London Greenpeace FILM Tmembers Helen Steel and Dave Seven years later, in February 2005, Morris, defended themselves in what the marathon legal battle finally McLibel is about the court case turned out to be Britain’s longest-ever concluded at the European Court of that was brought by McDonald’s in civil trial. Human Rights. And the result took Britain to stop the distribution of the everyone by surprise – especially the pamphlet ‘What’s wrong with McDon- McLibel is the story of two ordinary British Government. ald’s?’. The pamphlet made many people who humiliated McDonald’s in accusations against McDonald’s. the biggest corporate PR disaster in McLibel is not just about hamburgers. history. McDonald’s loved using the It is about the importance of freedom To understand what the case was UK libel laws to suppress criticism. of speech now that multinational about you need to study the pamphlet. Major media organizations like the corporations are more powerful than BBC and The Guardian crumbled and countries. It is a long pamphlet, so to make the apologized. task easier it has been divided into Filmed over ten years by no-budget sub-sections in Table 1 on (page 3). But then they sued gardener Helen Director Franny Armstrong, McLibel The whole class should look at the Steel and postman Dave Morris. -

Protecting Activists from Abusive Litigation: Slapps in the Global

PROTECTING ACTIVISTS FROM ABUSIVE LITIGATION SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH AND HOW TO RESPOND SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH Features and Policy Responses Author: Nikhil Dutta, Global Programs Legal Advisor, ICNL, [email protected]. Our thanks go to the following colleagues and partners for valuable discussions and input on this report: Abby Henderson; Charlie Holt; Christen Dobson; Ginna Anderson; Golda Benjamin; Lady Nancy Zuluaga Jaramillo; Zamira Djabarova; the Cambodian Center for Human Rights; iProbono; and SEEDS for Legal Initiatives. Published in July 2020 by the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL NORTH 2 III. SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH 4 A. Instances of Reported SLAPPs in the South 4 i. Thailand 5 ii. India 7 iii. Philippines 10 iv. South Africa 12 v. Other Instances of Reported SLAPPS in the South 13 B. Features of Reported SLAPPs in the South 15 IV. POLICY RESPONSES TO SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL NORTH 19 A. Enacting Protections for Public Participation 19 B. Creating Expedited Dismissal Procedures for SLAPPs 20 C. Endowing Courts with Supplemental Authorities to Manage SLAPPs 23 D. Permitting Recovery of Costs by SLAPP Targets 24 E. Authorizing Government Intervention in SLAPPs 25 F. Establishing Public Funds to Support SLAPP Defense 25 G. Imposing Compensatory and Punitive Damages on SLAPP Filers 25 H. Levying Penalties on SLAPP Filers 26 I. Reforming SLAPP Causes of Action 27 V. POLICY RESPONSES TO SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH 27 A. Thailand 28 B. Philippines 30 C. Indonesia 33 VI. DEVISING FUTURE RESPONSES TO SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH 33 REFERENCES 37 I. -

The Following Report Is No Longer Current, and Is to Be Used for Historical Purposes Only

The following report is no longer current, and is to be used for historical purposes only. CRIMES WITHOUT CONSEQUENCES: The Enforcement of Humane Slaughter Laws in the United States Researched and written by DENA JONES for the Animal Welfare Institute 2 CRIMES WITHOUT CONSEQUENCES: The Enforcement of Humane Slaughter Laws in the United States Researched and written by Dena Jones May 2008 Animal Welfare Institute Crimes Without Consequences: The Enforcement of Humane Slaughter Laws in the United States Researched and written by Dena Jones Animal Welfare Institute P.O. Box 3650 Washington, DC 20027 www.awionline.org Copyright © 2008 by the Animal Welfare Institute Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-938414-94-1 LCCN 2008925385 i CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 5 1.1 About the author........................................................................ 6 1.2 About the Animal Welfare Institute ........................................... 6 1.3 Acknowledgements ................................................................... 6 2. Overview of Food Animal Slaughter in the United States ...................... 7 2.1 Animals Slaughtered ................................................................. 7 2.2 Types of Slaughter Plants .......................................................... 12 2.3 Number of Plants ..................................................................... -

Legal Research Paper Series

Legal Research Paper Series NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY By Rita K. Lomio and J. Paul Lomio Research Paper No. 6 October 2005 Robert Crown Law Library Crown Quadrangle Stanford, California 94305-8612 NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRPAHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY I. Books II. Reports III. Law Review Articles IV. Newspaper Articles (including legal newspapers) V. Sound Recordings and Films VI. Web Resources I. Books RESEARCH GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Hoffman, Piper, and the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Guide to Animal Law Resources Hollis, New Hampshire: Puritan Press, 1999 Reference KF 3841 G85 “As law students, we have found that although more resources are available and more people are involved that the case just a few years ago, locating the resource or the person we need in a particular situation remains difficult. The Guide to Animal Law Resources represents our attempt to collect in one place some of the resources a legal professional, law professor or law student might want and have a hard time finding.” Guide includes citations to organizations and internships, animal law court cases, a bibliography, law schools where animal law courses are taught, Internet resources, conferences and lawyers devoted to the cause. The International Institute for Animal Law A Bibliography of Animal Law Resources Chicago, Illinois: The International Institute for Animal Law, 2001 KF 3841 A1 B53 Kistler, John M. Animal Rights: A Subject Guide, Bibliography, and Internet Companion Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000 HV 4708 K57 Bibliography divided into six subject areas: Animal Rights: General Works, Animal Natures, Fatal Uses of Animals, Nonfatal Uses of Animals, Animal Populations, and Animal Speculations. -

The Anticruelty Statute: a Study in Animal Welfare Darian M

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2006 The Anticruelty Statute: A Study in Animal Welfare Darian M. Ibrahim William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Ibrahim, Darian M., "The Anticruelty Statute: A Study in Animal Welfare" (2006). Faculty Publications. 1680. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1680 Copyright c 2006 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs THE ANTICRUELTY STATUTE: A STUDY IN ANIMAL WELFARE DARIAN M. IBRAHIM* IN TRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 175 I. ANIMAL RIGHTS, ANIMAL WELFARE, AND THE CONCEPT OF HUMANE EXPLOITATION ................................................................. 177 II. LEGISLATURES, SOCIETAL TENSION, AND THE INEFFECTIVE ANTICRUELTY STATUTE .................................................................. 179 A . The A nticruelty Statute ............................................................. 179 B. Understanding Anticruelty Statute Exemptions ........................ 182 1. Societal Preference ............................................................. 182 2. Legislative C apture ............................................................ 184 3. Animals as Legal Property ................................................. 187 4. Efficiency and Competency ............................................... 187 C. -

1 Articulating Animal Rights

1 Articulating Animal Rights: Activism, Networks and Anthropocentrism Eva Haifa Sarah Giraud Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2011 2 Abstract The thesis establishes a conversation between Donna Haraway and the work of contemporary UK animal rights groups, in order to develop their – respective – approaches to articulating animal rights issues. To analyse the tactics of these movements a conceptual framework is constructed through combining Haraway's insights with those of Bruno Latour, performative uses of actor- network theory and key concepts from Pierre Bourdieu (such as field, habitus and doxa). Through focusing on the tactics of UK animal rights groups the thesis works to recuperate certain of these practices from the criticisms Haraway levels at animal rights groups more broadly; illustrating contexts where these movements are departing from humanist rights-discourses and developing approaches more suited to the radical critique of anthropocentrism that is central to Haraway's own project. To develop a sense of the disparate approaches taken by these animal rights movements that complement Haraway's arguments, various online and offline tactics are analysed; drawing on a range of lobbying practices undertaken by movements involved in the vivisection debate (such as SPEAK and the BUAV), before focusing on more creative forms of vegan campaigning engaged in by local Nottingham groups (such as Veggies Catering Campaign and Nottingham Animal Rights). 3 Love and thanks to: Robin Shackford; for making me happy and centred, as well as hearing me repetitively go over my arguments. Annie Giraud; for love and support and everything else that I can‟t put into words. -

Mcspotlight Leaflet

The McSpotlight worldwide web site was launched on Feb 16th 1996 in London, Chicago, Helsinki and Is a high-fat, low-fibre diet linked to heart disease and cancer ? Auckland. Its aim is simple - to make freely available across the globe accurate, factual, up- to-date informa- tion about the McDonald's Corporation and all they stand for (of pressing importance given their ongoing attempts to silence their critics). In its first month it was accessed over a million times (including 1,300 times Are children being exploited by advertising ? by McDonald's themselves) and it has received press coverage all over the world: USA Today (front cover), Channel 4, Times of India, Chicago Tribune, BBC Radio 4, NBC TV, Die Tageszeitung, The Australian, Stern Do McDonald's exploit their low-paid, non-unionised workers ? magazine, Observer, Independent, LA Weekly, Helsingen Snomat (Finland) etc. Can mountains of disposable packaging be justified ? As one of the new breed of Internet sites starting to make full use of the world's most powerful communication system, McSpotlight combines text, graphics, video and audio into an accessible and interactive package that can be used by campaigners, journalists, researchers, scientists, and surfers Are McDonald's responsible for rainforest destruction ? alike - not to mention all McDonald's customers and employees wanting to find out the reality behind the Golden Arches. Do the billions of animals raised for the food industry suffer ? The infamous McLibel Trial and the issues at its heart (diet and ill-health, destruction of the environment, animal welfare, exploitation of children through advertising and workers through low pay) provide the focus Should cattle have priority over indigenous people for land ? for the site, but it is not just McDonald's in the McSpotlight. -

Revealed: Us Nukes on Uk Soil

REEDOM 8 0 p H A N A R C H I S T NEWS AND VIEWS www.freodompress.org.uk 5 MARCH 2005 Mega union merger Cultural cold war Rudolf Rocker reissued INSIDE ►► “"f2nmu,,el page 3 page 5 page 7 REVEALED: US NUKES ON UK SOIL report from America has for the And Closure (BRAC) review,” first time confirmed the presence The B61 bombs are ’free-fall’ weapons, A of nuclear weapons at RAF and must be carried by aircraft to their Lakenheath - with an explosive potential target. They have an explosive potential of 18,000 Hiroshima bombs. of 18,7 megatons. The Hiroshima US-based group the Natural Resources bomb was one kiloton. Defence Council (NRDC), using Freedom Before the report, it was believed that of information laws, claim to have found Lakenheath had moved half of them in a document signed by Clinton in 2000 1996-7. The 2000 directive however acknowledging the existence of 101 bombs. suggests this never happened. Potentially, Hans Kristensen, author of the report, they could be used in several areas at the said: “That document authorised the moment, Hans said: “They can potentially Pentagon to deploy 480 nuclear weapons be used against targets in Russia, Iran in Europe. And NATO says the number or Syria, I would remark that even if one has not been reduced since then.” believes the weapons serve a legitimate For the past decade, Lakenheath have purpose, the presence of such a large refused to confirm accusations that their number on NATO’s northern flank base holds nuclear materials. -

Whaling on Trial Whaling on Trial

Whaling on Trial Japan's whale meat scandal and the trial of the Tokyo Two l a i r t n o g n i l a h W Whaling on Trial This dossier outlines the key elements of Greenpeace's investigation of the Japanese government-sponsored whaling programme and the subsequent arrest, detention and prosecution of Junichi Sato and Toru Suzuki. The Whale The Meat Scandal Tokyo Two An informant's allegations, our The arrest of Junichi Sato subsequent investigation and the and Toru Suzuki, and the beginnings of the backlash against harshness of the Japanese Greenpeace in Japan criminal justice system The Struggle Information for a Fair Trial Unanswered questions, quick facts, timelines and how the Tokyo Two are being supported around the world. The pre-trial processes, and emerging clues for a cover-up Published in August 2010 For more information contact: [email protected] JN 298 greenpeace.org Whaling on Trial Japan's stolen whale meat scandal and the trial of the Tokyo Two © In early 2010, two Greenpeace activists went on trial in Japan in an unprecedented court case - one that court G R E E papers will register simply as a case of theft and trespass but which, over the course of the past two years, N P E has become so much more. Corrupt government practices, Japan’s adherence to international law, freedom A C E / of speech and the right of individual protest and the commercial killing of thousands of whales are all under the J E R E spotlight. Before the verdict has even been rendered, the United Nations has already ruled that, in the M Y S defendants' attempts to expose a scandal in the public interest, their human rights have been breached by U T T O the Japanese government. -

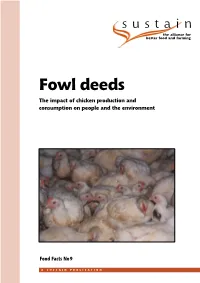

Fowl Deeds the Impact of Chicken Production and Consumption on People and the Environment

sustain the alliance for better food and farming Fowl deeds The impact of chicken production and consumption on people and the environment Food Facts No9 A SUSTAIN PUBLICATION What are ‘Food Facts’? There is growing concern about the quality of the food are not comprehensive dossiers, they are “sign-posting” we eat and drink - a recent poll1 showed that a majority documents, indicating the current scope of the debate of people now believe that food safety is deteriorating. and offering sources of further information. Many People are also worried about the environment and organisations in the Sustain membership (see inside back farming practices, and how our food production and cover) provide some of the best sources of such distribution systems may be contributing to problems information, and the Food Facts series is guided by a such as transport pollution, global warming and the loss working party (listed below) to whom we are indebted. of wildlife. The buoyant market for healthier foods, and However, the views expressed here do not necessarily exponentially growing sales for organically produced represent those of every member of the working party, foods show that many of us are prepared to make or of the Sustain membership as a whole. We are grateful positive choices to help tackle these problems. But our to the following organisations for supporting the ability to do so depends, among other things, on having production of the Food Facts series: Government’s the facts. This report is the ninth in a planned series of Environmental Action Fund, the Esmée Fairbairn twelve, all of which aim to provide information about the Charitable Trust, the Cobb Charity, the Cecil Pilkington positive and negative effects of food production methods Charitable Trust and the Chapman Charitable Trust. -

Framing PETA and Mcdonald's

Qualitative Methods Kate Nattrass Final Group Project Tamara Garcia Sarah Jones Ike Sharpless December 18, 2008 Framing PETA and McDonald’s: Assessing the Causes of Industry-Driven Farm Animal Welfare Measures “I think it would be a great thing if, you know, all these fast food outlets and these slaughterhouses and these laboratories and the bans that fund them exploded tomorrow.” -Bruce Friedrich, (then) PETA dir. of vegan outreach (Specter 2002) "If you're not going to say nice things about them no matter what…corporations have no reason to ever change their practices." -Bruce Friedrich, (now) PETA Vice President, praising McDonald’s decision to phase out growth-promoting antibiotics in its beef supply (Sanchez 2003) Background. The new millennium has brought with it a sea of change in how activists and companies interact; whereas activist organizations previously sought to influence corporate behavior primarily through lobbying and boycotts, many activist organizations now choose to work with rather than against the companies of which they are critical. (Browne and Schweikhard 2001) This trend is most pronounced in the formation of alliances between environmental groups and corporations, 1 (Economist 2008) but a comparable relationship may be emerging between animal activists and the giants of food retailing. Using a two year-long exchange between PETA and McDonald’s over farm animal welfare standards as a policy template, this paper examines two aspects of the role of stakeholder motivation in causing industry-driven change: assessing whether animal advocacy groups are pursuing this trend towards collaboration, and identifying the primary causal drivers of McDonald’s improved hen welfare standards. -

Saipan, MP.96950.'

-------· -..ill ~·~-! U~IV.!:.R.Slr.Y. OF HAWAII LIBRAA'( arianas %riet~~ Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 1972 '&1 ews Vol: 25 No .. 6~ . F,.• d· ay • June 20· ·1.997 . Saipan, MP.96950.' . :l!!iC,¢ ·. ©1997 Maria_nas Vari_ety . · . · . ' . , . · . Serving CNMl'for 25.Years iii ., . Chairman Young writes President Clinton: I I as.is' · I By Zaldy Dandan developed and adopted by the "Congress," he said, "has au Variety News Staff Northern Marianas pursuant to thorized the use of millions of THE chairman of the U.S. House the Covenant"has proved a highly dollars of Interior Department committee that has jurisdiction successful model." funds in order to ensure that other over the Northern Marianas is He added, "The increased level federal agencies and department against a federal takeover of the of economic development and are active participants in the CNMI's immigration and mini decreased reliance on federal Marianas and to contribute to the mum wage policies. funds further emphasizes the suc now long-overdue report." Congressman Don Young (R cess of self-government" in the Young said he will continue to Alaska), in a letter to President CNMI. monitor the situation in the CNMI, Clinton, said he is "not yet con Given the lack of timely report and will personally visit the Com vinced"that Congress should ''dis by the Clinton administration on monwealth with the members of turb" the CNMI's current setup, the CNMI's immigration and la the House Resources Committee. Young's letter followed a simi "particularly in view" of the Hay bor issues, Young said he was lar "reassurance" from the U.S.