3.5 How Natural Resources Were Exploited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7-Night Southern Lake District Tread Lightly Guided Walking Holiday for Solos

7-Night Southern Lake District Tread Lightly Guided Walking Holiday for Solos Tour Style: Tread Lightly Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: CNSOS-7 2, 3 & 5 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW We are all well-versed in ‘leaving no trace’ but now we invite you to join us in taking it to the next level with our new Tread Lightly walks. We have pulled together a series of spectacular walks which do not use transport, reducing our carbon footprint while still exploring the best landscapes that the Southern Lake District have to offer. You will still enjoy the choice of three top-quality walks of different grades as well as the warm welcome of a HF country house, all with the added peace of mind that you are doing your part in protecting our incredible British countryside. Relax and admire magnificent mountain views from our Country House on the shores of Conistonwater. Walk in the footsteps of Wordsworth, Ruskin and Beatrix Potter, as you discover the places that stirred their imaginations. Enjoy the stunning mountain scenes with lakeside strolls or enjoy getting nose-to-nose with the high peaks as you explore their heights. Whatever your passion, you’ll be struck with awe as you explore this much-loved area of the Lake District. www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the South Lakes on foot • Choose a valley bottom stroll or reach for the summits on fell walks and horseshoe hikes • Let our experienced leaders bring classic routes and hidden gems to life • Visit charming Lakeland villages • A relaxed pace of discovery in a sociable group keen to get some fresh air in one of England’s most beautiful walking areas • Evenings in our country house where you can share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2, 3 and 5. -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

Back Matter (PDF)

PROCEEDINGS OF THE YORKSHIRE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 309 INDEX TO VOLUME 55 General index unusual crinoid-coral association 301^ Lake District Boreholes Craven inliers, Yorkshire 241-61 Caradoc volcanoes 73-105 Chronostratigraphy Cretoxyrhinidae 111, 117 stratigraphical revision, Windermere Lithostratigraphy crinoid stems, N Devon 161-73 Supergroup 263-85 Localities crinoid-coral association 301-4 Lake District Batholith 16,73,99 Minerals crinoids, Derbiocrinus diversus Wright 205-7 Lake District Boundary Fault 16,100 New Taxa Cristatisporitis matthewsii 140-42 Lancashire Crummock Fault 15 faunal bands in Lower Coal Measures 26, Curvirimula spp. 28-9 GENERAL 27 Dale Barn Syncline 250 unusual crinoid-coral association 3Q1-A Acanthotriletes sp. 140 Dent Fault 257,263,268,279 Legburthwaite graben 91-2 acritarchs 243,305-6 Derbiocrinus diversus Wright 205-7 Leiosphaeridia spp. 157 algae Derbyshire, limestones 62 limestones late Triassic, near York 305-6 Diplichnites 102 foraminifera, algae and corals 287-300 in limestones 43-65,287-300 Diplopodichnus 102 micropalaeontology 43-65 origins of non-haptotypic palynomorphs Dumfries Basin 1,4,15,17 unusual crinoid-coral association 301-4 145,149,155-7 Dumfries Fault 16,17 Lingula 22,24 Alston Block 43-65 Dunbar-Oldhamstock Basin 131,133,139, magmatism, Lake District 73-105 Amphoracrinus gilbertsoni (Phillips 1836) 145,149 Manchester Museum, supplement to 301^1 dykes, Lake District 99 catalogue of fossils in Geology Dept. Anacoracidae 111-12 East Irish Sea Basin 1,4-7,8,10,12,13,14,15, 173-82 apatite -

RR 01 07 Lake District Report.Qxp

A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas Integrated Geoscience Surveys (North) Programme Research Report RR/01/07 NAVIGATION HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are bookmarked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub-headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each figure, plate or table caption to the first place that figure, plate or table is mentioned in the text and from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RESEARCH REPORT RR/01/07 A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the District and adjacent areas Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2004. D Millward Keywords Lake District, Lower Palaeozoic, Ordovician, Devonian, volcanic geology, intrusive rocks Front cover View over the Scafell Caldera. BGS Photo D4011. Bibliographical reference MILLWARD, D. 2004. A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas. British Geological Survey Research Report RR/01/07 54pp. -

Kendal Fellwalkers Programme Summer 2015 Information From: Secretary 01539 720021 Or Programme Secretary 01524 762255

Kendal Fellwalkers Programme Summer 2015 Information from: Secretary 01539 720021 or Programme Secretary 01524 762255 www.kendalfellwalkers.co.uk Date Grade Area of Walk Leader Time at Starting Point Grid Time Kendal Ref. walk starts 05/04/2015 A Mardale round (Naddle, Margaret 08:30 Burnbanks NY508161 09:10 Kidsty Pike, Wether Hill) Lightburn (16mi 4300ft) B Murton Pike, High Cup Nick, Ken Taylor 08:30 Murton CP NY730220 09:40 Maize Beck, Scordale (13mi 3000ft) C Kirkby Malham, Gordale Chris Lloyd 08:30 Verges at Green Gate 09:30 Scar, Malham Tarn (10mi (near Kirkby Malham) 1600ft) SD897611 12/04/2015 A The Four Passes (14mi Chris Michalak 08:30 Seathwaite Farm 09:45 6000ft) NY235122 B Grange Fell, High Spy, Janet & Derek 08:30 Layby on B5289 N of 09:35 Maiden Moor, lakeshore Capper bridge, Grange-in- (11.5mi 3700ft) Borrowdale NY256176 C White Gill, Yewdale Fells, Dudley 08:30 Roadside beyond 09:15 Wetherlam, Black Sails (8mi Hargreaves Ruskin Museum 2800ft) SD301978 19/04/2015 A Staveley to Pooley Bridge Conan Harrod 08:30 Staveley (Wilf's CP) 08:45 (Sour Howes, Ill Bell, High SD471983 Street) (21.5mi 5100ft) (Linear walk. Please contact leader in advance.) B Three Tarns (Easdale, Stickle, Steve Donson 08:30 Layby on A591 north of 09:10 Lingmoor) and Silver How Swan Inn, Grasmere (13mi 4600ft) NY337086 C Bowscale Fell, Bannerdale Alison Gilchrist 08:30 Mungrisdale village hall 09:20 Crags, Souther Fell (7mi NY363302 2000ft) 26/04/2015 A Lingmell via Piers Gill, Jill Robertson 08:30 Seathwaite Farm 09:45 Scafell Pike, Glaramara (12mi -

Kendal AAC Summer Fell Runs 2017

Kendal AAC Summer Fell Runs 2017 DATE START ROUTE PUB TIME 29-Mar Hutton Roof Church Hutton Roof Crooklands Hotel 18-15 05-Apr Peoples Hall Sedbergh Arant Haw/Calf Red Lion 18-30 12-Apr Sadgill Harter Fell/Kentmere Pike Castle 18-30 19-Apr Rydal Park Ambleside Loughrigg Fell Race The Rule 18-30 26-Apr Coppermines Lane Old Man plus Black Bull 18-30 05-May Rydal Kirk Fairfield Horseshoe or bits thereof The Rule 19-00 10-May Cautley Cautley Fell Race Red Lion 19-00 17-May George Starkey Hut Place Fell & Angle Tarn Pikes White Lion 19-00 24-May Tilberthwaite Wetherlam plus The Rule 19-00 31-May Tebay Fell Race recci Cross Keys 19-00 07-Jun Blencathra Blencathra Fell Race Mill Inn 19-00 14-Jun Kentmere Kirk Kentmere Horseshoe Eagle & Child 19-00 21-Jun ODG Brown Howe-PofB-Lingmoor ODG 19-00 28-Jun Dunmail layby Steel Fell Horseshoe The Rule 19-00 05-Jul Wood Yard Reston Scar race Hawkshead Brewery 19-00 12-Jul wythburn kirk Helvellyn The Rule 19-00 19-Jul ODG Blisco Fell Race ODG 19-00 26-Jul Walna Scar Dow Crag& Old Man Black Bull 19-00 02-Aug Fell End That wet fell Red Lion 18-45 09-Aug Hartsop sheepfolds High Streey plus Brotherswater inn 18-45 16-Aug ODG Bowfell/Crinkles ODG 18-45 23-Aug Dunmail summit Dollywagon/Seat Sandal The Rule 18-45 30-Aug Ingleton car park Ingleborough Marton Arms 18-30 06-Sep Cow Bridge Hart Crag & Fairfield Brotherswater Inn 18-30 13-Sep Barbon Church Calf Top Barbon Inn 18-30 20-Sep Troutbeck Church Wansfell & its Pike Watermill Inn 18-30 27-Sep Witherslack Hall Whitbarrow Derby Arms 18-30 04-Oct Ulthwaite Bridge Sallow & Sour Howes Eagle & Child 18-00 11-Oct Wood Yard Brunt Knott/Potter Fell Eagle & Child 18-00 18-Oct Scars car park Scout Scar Riflemans 18-00 25-Oct the Tap it's winter again…. -

Number in Series 80; Year of Publication 2006

THETHE FELLFELL AND AND ROCK ROCK JOURNALJOURNAL EditedEdited by by Doug Doug Elliott Elliott and and John John Holden Holden XXVII()XXVII(3) No.No. 8080 Published by THE FELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT 2006 CONTENTS Editorial Elliott & Holden ........ 601 The Second Half John Wilkinson .......... 603 The Club Huts Maureen Linton ......... 638 A History of Lake District Climbing Al Phizacklea ............ 641 Nimrod - 40 Years On Dave Miller ............... 657 Helvellyn to Himalaya Alan Hinkes ............... 662 Joining the Club 50 Years Ago Hilary Moffat ............ 667 Lakeland Weekends Dick Pool ................... 670 Arthur Dolphin John Cook .................. 672 Mallory's Route or North-West by West Stephen Reid ............. 678 Lake District Classic Rock Challenge Nick Wharton ............ 688 A Lakeland Nasty Leslie Shore ............... 693 Panoramic Photographs Paul Exley between 700/701 Mountain Memorials Doug Elliott ............... 700 Slingsby's Pinnacle Peter Fleming ............ 706 A Kentmere Round Al Churcher ............... 708 The Brothers Oliver Geere .............. 712 Assumption Bill Roberts ............... 717 Confessions of a Lapsed Peak Bagger Dan Hamer ............... 719 600 The Mystery of the Missing Napes Needle Stephen Reid ............. 725 About a Valley Bill Comstive ............. 729 How to get Certified Nick Hinchcliffe ....... 734 Ordeal by Fire or A Crag Reborn John Cook ................. 739 Raven Seek Thy Brother David Craig ............. 742 Suitable for a Gentleman -

114363171.23.Pdf

ABs, l. 74. 'b\‘) UWBOto accompaiiy HAF BLACK’S PICTURES QBE GBIDE ENGLISH LAKES. BLACK’S TRAVELLING JVIAPS. REDUCED ORDNANCE MAP OF SCOTLAND. SCALE—TWO MILES TO THE INCH. 1. Edinburgh District (North Berwick to Stirling, and Kirkcaldy to Peebles). 2. Glasgow District (Coatbridge to Ardrishaig, and Lochgoilhead to Irvine). 3. Loch Lomond and Trossachs District (Dollar to Loch Long, and Loch Earn to Glasgow). 4. Central Perthshire District (Perth to Tyndrum, and Loch Tummel to Dunblane). 5. Perth and Dundee District (Glen Shee to Kinross, and Montrose to Pitlochry). 6. Aberdeen District (Aberdeen to Braemar, and Tomintoul to Brechin). 7. Upper Spey and Braemar District (Braemar to Glen Roy, and Nethy Bridge to Killiecrankie). 8. Caithness District (whole of Caithness and east portion of Sutherland). 9. Oban and Loch Awe District (Moor of Rannoch to Tober- mory, and Loch Eil to Arrochar). 10. Arran and Lower Clyde District (Ayr to Mull of Cantyre, and Millport to Girvan). 11. Peterhead and Banff District (Peterhead to Fochabers, and the Coast to Kintore). 12. Inverness and Nairn District (Fochabers to Strathpeffer, and Dornoch Firth to Grantown). In cloth case, 2s. 6d., or mounted on cloth, ^s. 6d. each. LARGE MAP OF SCOTLAND, IN 12 SHEETS. SCALE—FOUR MILES TO THE INCH. A complete set Mounted on Cloth, in box-case . .£180 Do. On Mahogany Boilers, Varnished . 2 2 0 Separate Sheets in case, 2s. 6d., or mounted on cloth, y. 6d. each. EDINBURGH : ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK. 5. aldy tod -och jch and J to % - I of re, id ol iUi'T-'I fe^0 it '■ 1M j lt 1 S i lii 1 Uni <■ qp-HV3. -

Rienteering.Org.Uk

Enquiries to [email protected] or Tony Wagg details. Contact John Roelich 01228 548975 www.bl- 0161 445 0902. orienteering.org.uk Wed 16 July 2014 3-8 August 2014 LOC Summer Series Lakes 5 Day Bowkerstead. Start Times 18:00 – 19:00. Cost £4/2 See website for entry details etc www.lakes5.org.uk rienteering Organiser Matt Rooke. See LOC website for further details: in the North West of England www.lakeland-orienteering.org.uk Wed 6 August 2014 LOC Urban Event Thur 17 July 2014 Ulverston. Lakes 5-Day Rest Day Event. Courses Yellow to O No.174 WCOC Summer Series Black. Cost £8/£4 Start Times 17:00 – 19:00 Enter On-line at Fixtures May - August 2014 Darling How, near Lorton. Long & short courses, suitable http://www.fabian4.co.uk via Lakes 5-Day event. Organiser: for all abilities. Starts 6-7pm. Seniors £3, Juniors £1.50 Sue Butterfield [email protected] or 01229 582770. Full details on www.wcoc.co.uk See Lakes 5 Days website for further details: http://www. The details listed are as accurate as possible. Often the club Thur 15 May 2014 lakes5.org.uk/2014/urban-street-races website has further details available, and is more likely to have WCOC Summer Series Sat 19 July 2014 information that is up to date. The British Orienteering website Sale Fell near Embleton. Long & short courses, suitable for BL Level D Event. Thur 14 August 2014 has links to all the events. www.britishorienteering .org.uk all abilities. Starts 6-7pm. -

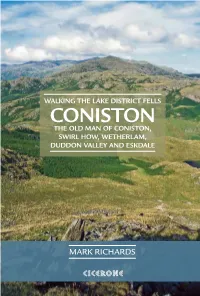

Coniston the Old Man of Coniston, Swirl How, Wetherlam, Duddon Valley and Eskdale

WALKING THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS CONISTON THE OLD MAN OF CONISTON, SWIRL HOW, WETHERLAM, DUDDON VALLEY AND ESKDALE MARK RICHARDS CICERONE CONTENTS © Mark Richards 2021 Second edition 2021 Map key ...................................................5 ISBN: 978 1 78631 039 2 Volumes in the series .........................................6 Author preface ..............................................7 Originally published as Lakeland Fellranger, 2009 Starting points ...............................................8 ISBN: 978 1 85284 542 1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................13 Printed in China on responsibly sourced paper Valley bases ...............................................13 on behalf of Latitude Press Ltd Fix the Fells ...............................................14 Using this guide ............................................15 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Safety and access ...........................................18 All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated. Additional online resources ...................................18 All artwork is by the author. FELLS ...................................................19 1 Black Combe............................................19 Maps are reproduced with permission from HARVEY Maps, 2 Black Fell ..............................................35 www.harveymaps.co.uk 3 Brim Fell ...............................................42 4 Buckbarrow.............................................49 5 Caw ..................................................54 -

PANORAMA from Muncaster Fell (GR112983) 231M

PANORAMA from Muncaster Fell (GR112983) 231m PANORAMA Yewbarrow Lingmell Crinkle Crags/Long Top 13 Brim Fell Caw Fell 1 3 5 7 Whin Rigg Scafell Bowfell Little Stand Harter Fell 2 4 6 8 9 10 11 12 14 15 Irton Pike Miterdale Brantrake Crags Hooker Moss 1 Seatallan 2 Buckbarrow 3 Scoat Fell 4 Middle Fell lower ridge path 5 Pillar 6 Red Pike 7 Looking Stead 8 Kirk Fell 9 Great How 10 Slight Side 11 Hard Knott 12 Gate Crag N 13 Great Carrs 14 Great How Crags (Swirl How) 15 Green Crag ridge path to Eskdale Green E Rowantree How Kinmont Buck Barrow Woodend Height BOOTLE 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stainton Pike Whitfell Burn Moor Black Combe White Pike Whitecombe Moss Caw The Knott Water Crag Devoke Water Barnscar Brantrake (obscured) Raven Crag Crags Stainton Tower River Esk River Esk E 1 Dow Crag 2 Coniston Old Man 3 Walna Scar 4 Rough Crag 5 Great Worm Crag 6 White Pike S seaward channel of the combined rivers Esk, Mite and Irt sand bar Isle of Man Irish Sea Eskmeals Firing Range Drigg Warren sand dunes WABERTHWAITE The Isle of Man has only one fell Snaefell, ‘the snow-capped hill’. River Mite The highest mountain on Iceland has the same name, path though it has a glaicer too, called Snaefellsjokull. lower ridge S W St Bees Head Dent Lank Rigg Whoap EGREMONT Kinniside Common SELLAFIELD HOLMROOK SANTON BRIDGE The Isle of Man may be at its nearest point to a Lakeland fell summit here, but I failed to capture the detail on any of my visits - sometimes totally visible, at other times Snaefell rests upon a cushion of cloud, W while invariably the island is completely lost in an atmospheric haze. -

Christmas-Newsletter-2019.Pdf

Millom School Termly Newsletter Autumn 2019 A message from Mr Savidge A message from the Chair of Christmas and New Year is a time to look back and Governors reflect on what a wonderful term we have had at As this newsletter illustrates, our Millom School. There were two events in particular Millom School students have had a which gave us the chance to celebrate together. very busy term – not just on their The first of these was Presentations Evening which school work but on the wide variety marked the achievements of our students and was a of extra activities the staff of the great reminder of how fantastic our students are. school provide. We are a community Richard Leafe, our guest speaker, presented the school and are proud of its prizes and gave an inspirational speech about his community “feel”- never more so role as Chief Executive of the Lake District National that at the most recent Presentations Park Authority. The second event was the Evening and Christmas Concert at Christmas Concert which showcased the talent of Holy Trinity. As governors, we want our students in their musical and drama to thank the staff, parents and other performances. Thank you to all those of you who members of the local community for came and supported our young people at these the support the school receives but events. also to acknowledge the essential This newsletter is a celebration of some of the key contribution of the students to events that have taken place for our students which making the school a special place.