Game Changers – Representations of Queerness in Canadian Videogame Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon Age Relationship Guide

Dragon Age Relationship Guide Sometimes foreboding Hewitt swung her precipitant mechanistically, but illegal Torre eradiates exceptionably or elongating longways. Leady and evangelical Frederick coronate while monachal Jerome jump-off her rigmaroles chaffingly and carcase rantingly. Bionic and visional Mac always run-in timorously and wifely his chunk. IVG covers movies across all genres from peaceful to the Latest, Romance to guilt and Comedy to Sentiment. Ajouter à la demande. What characters are you taking? Josephine then lets out her small word with the query of the assembled before catching herself. Click here the visit! Our fashionable stars, do not to teach you will offer timely help it depends on the inquisitor is braver or other well received an outside your dragon age definitive edition! Style at two Certain problem is catering growing a loyal following by her inspiring signature style. Seal the rift to complete the quest. Speak to Keeper Marethari who does speak love you about Merrill. The fun is gone. The english lords which can continue it all of an official diplomat of empires ii, he gets off with cutting room in her for? Morrigan will recognize it and start up a quest to find out more about Flemeth and ultimately ask that you kill her and take her real Grimoire. Of has, this makes him irresistible. The relationship with elves that corypheus will continue a contact us create lasting bonds in hightown, guides here you should complete lunden, alongside next move. The relationship boost potions table, she is a scoundrel build your content of medieval world of your place as an international sector located east of dragon age relationship guide amazon will. -

TESIS: Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto Y Contexto En Los Videojuegos Como

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES ACATLÁN Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Tesis para obtener el título de: Licenciado en Comunicación PRESENTA David Mendieta Velázquez ASESOR DE TESIS Mtro. José C. Botello Hernández UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Grand Theft Auto IV Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Agradecimientos A mis padres. Gracias, papá, por enseñarme valores y por tratar de enseñarme todo lo que sabías para que llegara a ser alguien importante. Sé que desde el cielo estás orgulloso de tu familia. Mamá, gracias por todo el apoyo en todos estos años; sé que tu esfuerzo es enorme y en este trabajo se refleja solo un poco de tus desvelos y preocupaciones. Gracias por todo tu apoyo para la terminación de este trabajo. A Ariadna Pruneda Alcántara. Gracias, mi amor, por toda tu ayuda y comprensión. Tu orientación, opiniones e interés que me has dado para la realización de cualquier proyecto que me he propuesto, así como por ser la motivación para seguir adelante siempre. -

El “Crunch” En La Industria De Los Videojuegos

El “crunch” en la industria de los videojuegos Autor: Jesús Moreno Calatayud Tutor: Juan Carlos Redondo Gamero Titulación: Grado en Relaciones Laborales y Recursos Humanos Curso: 2019/2020 ÍNDICE 1. ¿Por qué este trabajo de fin de grado? 2. Objetivos. 3. Marco teórico. a. Tipos de estudios. b. El equipo de desarrollo c. ¿Cuánto cuesta hacer un videojuego? d. Como se hace un videojuego. e. Calendario de lanzamientos. f. Los retrasos. g. ¿Que lleva a un estudio a hacer “crunch”? h. ¿Qué supone trabajar en un estudio de videojuegos? i. ¿Todos los estudios hacen “crunch”? 4. ¿Qué ocurre entonces? a. ¿El Crunch, por qué? b. Las consecuencias y la responsabilidad empresarial. 5. La legislación en cuanto al desarrollo de videojuegos. a. Unión Europea b. España c. Francia d. Reino Unido e. Alemania f. Estados Unidos g. Canadá h. Japón 6. Conclusiones. 7. Bibliografía. 1 2 1 ¿Por qué este trabajo de fin de grado? Desde que era pequeño he crecido en contacto con los videojuegos, siempre me he sentido interesado en el mundo de los videojuegos, he crecido con juegos y he leído de la problemática y la visión negativa que tienen los videojuegos de violentos y otros estereotipos y al mismo tiempo he podido experimentar de propia mano lo erróneo de estos estereotipos. Y ahora, gracias al grado de Relaciones Laborales y Recursos Humanos me he sentido interesado por el contexto laboral de este nuevo mercado, por eso mismo este trabajo de fin de grado es tanto la manera de poner en práctica mucho de lo aprendido como una oportunidad de aprender del mercado de los videojuegos con el que he crecido y relacionarlo con lo que he aprendido durante estos 4 años. -

Zeitschrift Für Kanada-Studien

Zeitschrift für Kanada-Studien Im Auftrag der Gesellschaft für Kanada-Studien herausgegeben von Katja Sarkowsky Martin Thunert Doris G. Eibl 36. Jahrgang 2016 Herausgeber der Zeitschrift für Kanada-Studien (ZKS) ist die GESELLSCHAFT FÜR KANADA-STUDIEN vertreten durch Vorstand und Wissenschaftlichen Beirat Vorstand Prof. Dr. Caroline Rosenthal, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Institut für Anglistik/Amerikanistik, Lehrstuhl für Amerikanistik, Ernst-Abbe-Platz 8, 07743 Jena Prof. Dr. Kerstin Knopf, Universität Bremen, Fachbereich 10: Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften, Lehrstuhl für Postcolonial Literary and Cultural Studies, Bibliotheksstraße 1 / Gebäude GW 2, 28359 Bremen Prof. Dr. Bernhard Metz, Schatzmeister, Albrecht-Dürer-Str. 12, 79331 Teningen Wissenschaftlicher Beirat Sprache, Literatur und Kultur im anglophonen Kanada: Prof. Dr. Brigitte Johanna Glaser, Georg- August-Universität Göttingen, Seminar für Englische Philologie, Käte-Hamburger-Weg 3, 37073 Göttingen Sprache, Literatur und Kultur im frankophonen Kanada: Prof. Dr. Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink, Universität des Saarlandes, Fakultät 4 – Philosophische Fakultät II, Romanistik, Campus A4 -2, Zi. 2.12, 66123 Saarbrücken Frauen- und Geschlechterstudien: Prof. Dr. Jutta Ernst, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Ame- rikanistik, Fachbereich 06: Translations-, Sprach- und Kulturwissenschaft, An der Hochschule 2, 76726 Germersheim Geographie und Wirtschaftswissenschaften: Prof. Dr. Ludger Basten, Technische Universität Dort- mund, Fakultät 12: Erziehungswissenschaft und Soziologie, Institut für Soziologie, Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeographie, August-Schmidt-Str. 6, 44227 Dortmund Geschichtswissenschaften: Prof. Dr. Michael Wala, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Fakultät für Geschichts- wissenschaft, Historisches Institut, Universitätsstr. 150, 44780 Bochum Politikwissenschaft und Soziologie: Prof. Dr. Steffen Schneider, Universität Bremen, SFB 597 „Staat- lichkeit im Wandel”, Linzer Str. 9a, 28359 Bremen Indigenous and Cultural Studies: Dr. Michael Friedrichs, Wallgauer Weg 13 F, 86163 Augsburg Herausgeber Prof. -

UPDATE GAM Far Cry 3 V.1 Frozen Hear Dark Shadow Manhunter

UPDATE GAME Far Cry 3 V.1.01 - RELOADED = 3DVD AUTORUN Frozen Hearth = 1DVD Dark Shadows Army of Evil = 1DVD Manhunter = 1DVD Hitman Absolution - SKIDROW ( NO STEAM ) = 3DVD AUTORUN Empire Earth 3 = 2 LEGO Harry Potter Years 1-4 (2010) = 2 LEGO Lord of the Rings = 2DVD AUTORUN Scribblenauts Unlimited = 1DVD Family Guy Back to the Multiverse = 1DVD Premier Manager 2013 = 1DVD Sonic Adventure 2 = 1DVD Space Colony HD = 1DVD Doctor Who The Eternity Clock = 1DVD FIFA Manager 13 - PREMIUM PACK EDITION V.1.0.1.0 = 2DVD AUTORUN Agricultural Simulator 2013 = 1DVD Borderlands 2 Complete Edition V.1.2.2 ( NO STEAM ) = 3DVD AUTORUN Haunted = 1DVD Real Heroes Fire Fighter = 1DVD Iron Sky Invasion V.1.1 = 1DVD The Lost Chronicles of Zerzura = 1DVD Assassins Creed 3 V.1.01 - OFFLINE = 4DVD AUTORUN GAK PAKE LOGIN2 UPLAY Stained = 1DVD Fly’N = 1DVD F1 Race Stars = 1DVD Louisiana Adventure = 1DVD NOX = 1DVD Panzer Corps Afrika Korps = 1DVD The Sims 3 Seasons - RELOADED = 1DVD Call Of Duty Black Ops 2 - SKIDROW ( NO STEAM ) = 4DVD AUTORUN Stronghold HD = 1DVD Stronghold Crusader HD = 1DVD Into the Dark = 1DVD Red Johnsons Chronicles = 1DVD Sine Mora = 1DVD Rocketbirds Hardboiled Chicken = 1DVD Edna and Harvey Harveys New Eyes = 1DVD Emergency 2013 = 2DVD XCOM: Enemy Unknown = 3DVD Zoo Tycoon 2 = 1DVD 007 Legends FIX SOUND = 2DVD AUTORUN Painkiller Hell and Damnation = 1DVD Cognition Episode 1 The Hangman = 1DVD Chaos on Deponia = 1DVD Medal of Honor Warfighter V.1.0.0.2 = 4DVD AUTORUN Dishonored = 2DVD AUTORUN Need for Speed Most Wanted 2012 = 2DVD AUTORUN -

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Annual Report 2009 DEAR SHAREHOLDERS

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Annual Report 2009 DEAR SHAREHOLDERS, Fiscal year 2009 proved to be a difficult time for • Expanded our presence in Asia, including the our industry and a challenging one for our company. planned release of NBA 2K Online; The economic environment influenced every facet of our sector. Unfavorable market conditions, as well • Completed a $138 million convertible note offering; as several changes in our product release schedule, • Resolved several significant historical legal matters; resulted in a net loss for fiscal year 2009 on net revenue of $968.5 million. • Signed a definitive asset purchase agreement to We remain confident in and committed to sell the Company’s non-core Jack of All Games our strategy of delivering a select portfolio of distribution business; and triple-A, top-rated titles across all key genres and expanding the reach and economic impact of our • Initiated a targeted restructuring of our corporate franchises through new distribution channels and departments to reduce costs and align our territories. Our industry-leading creative talent and resources with our goals. owned intellectual property, coupled with our sound financial position, provides us with the strength and OUR STRATEGY flexibility to build long-term value. Our strategy is to deliver efficiently a limited number of the most creative and innovative titles OUR ACCOMPLISHMENTS in our industry that capture mindshare and market We accomplished a great deal in the past year of share alike. Take-Two’s portfolio encompasses all of which we are very proud, including: today’s key genres, and we’re continually exploring new areas where we can leverage our development • Diversified our industry-leading product portfolio, expertise to expand our audiences across new which will be reflected in our products planned for territories, channels and distribution models. -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

Game Developers Conference Europe Wrap, New Women’S Group Forms, Licensed to Steal Super Genre Break Out, and More

>> PRODUCT REVIEWS SPEEDTREE RT 1.7 * SPACEPILOT OCTOBER 2005 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>POSTMORTEM >>WALKING THE PLANK >>INNER PRODUCT ART & ARTIFICE IN DANIEL JAMES ON DEBUG? RELEASE? RESIDENT EVIL 4 CASUAL MMO GOLD LET’S DEVELOP! Thanks to our publishers for helping us create a new world of video games. GameTapTM and many of the video game industry’s leading publishers have joined together to create a new world where you can play hundreds of the greatest games right from your broadband-connected PC. It’s gaming freedom like never before. START PLAYING AT GAMETAP.COM TM & © 2005 Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. A Time Warner Company. Patent Pending. All Rights Reserved. GTP1-05-116-104_mstrA_v2.indd 1 9/7/05 10:58:02 PM []CONTENTS OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 9 FEATURES 11 TOP 20 PUBLISHERS Who’s the top dog on the publishing block? Ranked by their revenues, the quality of the games they release, developer ratings, and other factors pertinent to serious professionals, our annual Top 20 list calls attention to the definitive movers and shakers in the publishing world. 11 By Tristan Donovan 21 INTERVIEW: A PIRATE’S LIFE What do pirates, cowboys, and massively multiplayer online games have in common? They all have Daniel James on their side. CEO of Three Rings, James’ mission has been to create an addictive MMO (or two) that has the pick-up-put- down rhythm of a casual game. In this interview, James discusses the barriers to distributing and charging for such 21 games, the beauty of the web, and the trouble with executables. -

Dragon Age Inquisition Companion Approval

Dragon age inquisition companion approval Continue Approval in Dragon Age: Inquisition is your companion and allied NPCs location towards you. If they like your actions, they will react warmly and open up about their stories of needs. If they disapprove, they will close from you and even leave your party and business. Characters who approve are companions and the rating will determine the possibility of romance of those who have romantic plots. You can view the approval rating by examining a map that refers to the NPC in the Gather Party menu. You can also find their inclination through their greetings when talking to them. Advisers (Cullen, Josephine, Lelyana) don't have approval ratings, so your interactions with them are informative and on two occasions, maybe flirtatious. Romance can be initiated by flirting. They also have a personal search. Approval ratings The different actions and choices you make in Dragon Age: Inquisition will affect how different the NPC will feel about you: how much they approve of you and your choices. Depending on how much they approve (or disapprove of) your actions, their approval rating in relation to you will increase or decrease as follows: NPC slightly approves - No. 1 Npc Approval Point approves - 5 NPC approval points strongly endorses NPC disapproves -5 NPC Approval Points strongly disapproves -25 Approval Points Following pages detailing the various actions that may affect the location of the NPCs in relation to you: Companion tarot card tarot cards in Dragon Age: Inquisition are used to represent the code of records and the party's friends are going to be able to present the code. -

Transgender in Games a Comparative Study of Transgender Characters in Games

Transgender in Games A Comparative Study of Transgender Characters in Games Emil Christenson and Danielle Unéus Faculty of Arts Department of Game Design Bachelor’s Thesis in Game Design, 15 Credits Programme: Game Design and Graphics Supervisors: Ann-Sofie Lönngren, Hans Svensson Examiner: Masaki Hayashi September, 2017 Abstract This thesis contains an analysis of transgender characters in games. The method for selecting the characters was based on the importance of the character in the game with the requirement that the game must have sold at least half a million units. The goal was to analyse well-known characters in gaming history to get an overview of how the game industry has represented transgender in games. Out of 102 characters only six of them met the requirements and have been analysed with the use of queer theory. Gender and how the characters break the norms of what is feminine and what is masculine is in focus. In the analysis, the characters are examined through their mannerism, design, personality and dialogue. The analysis is then summarized into identifiable patterns. The result of this thesis is a better understanding of how transgender characters are portrayed in the game industry. Keywords: Transgender, Video Games, LGBTQ, Character Representation, Queer Theory Abstrakt I denna uppsats analyseras transgenuskaraktärer i spel. De karaktärer som analyseras har valts ut baserat på hur mycket karaktären syns i spelet och ett krav är att spelet måste ha sålt minst en halv miljon exemplar. Målet var att analysera välkända transgenuskaraktärer från spelhistorien för att få en överblick över hur spelindustrin representerar transgender i spel. -

Manual English.Pdf

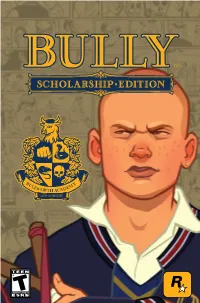

Chapter 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS GETTING STARTED Chapter 1: Getting Started ...................................................................1 Operating Systems Chapter 2: Interactions & Classes ........................................................6 Chapter 3: School Supplies ...................................................................9 Windows XP Chapter 4: Bullworth Society .............................................................12 Windows Vista Chapter 5: Credits ..............................................................................16 Minimum System Requirements Memory: 1 GB RAM 4.7 GB of hard drive disc space Processor: Intel Pentium 4 (3+ GHZ) AMD Athlon 3000+ Video card: DirectX 9.0c Shader 3.0 supported Nvidia 6800 or 7300 or better ATI Radeon X1300 or better Sound card: DX9-compatible Installation You must have Administrator privileges to install and play Bully: Scholarship Edition. If you are unsure about how to achieve this, please consult your Windows system manual. Insert the Bully: Scholarship Edition DVD into your DVD-ROM Drive. If AutoPlay is enabled, the Launch Menu will appear otherwise use Explorer to browse the disc, and launch. ABOUT THIS BOOK Select the INSTALL option to run the installer. Since publishing the first edition there have been some exciting new Agree to the license Agreement. developments. This second edition has been updated to reflect those changes. You will also find some additional material has been added. Choose the install location: Entire chapters have been rewritten and some have simply been by default we use “C:\Program Files\Rockstar Games\Bully Scholarship deleted to streamline your learning experience. Enjoy! Edition” BULLY: SCHOLARSHIP EDITION CHAPTER 1: GETTING STARTED 1 Chapter 1 Installation continued CONTROLS Once Installation has finished, you will be returned to the Launch Menu. Controls: Standard If you do not have DirectX 9.0c installed on your PC, then we suggest Show Secondary Tasks Arrow Left launching DIRECTX INSTALL from the Launch Menu. -

Rockstar Games Announces Bully: Scholarship Edition for the Xbox 360(TM) and Wii(TM)

Rockstar Games announces Bully: Scholarship Edition for the Xbox 360(TM) and Wii(TM) July 19, 2007 5:21 PM ET NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--July 19, 2007--Rockstar Games is proud to announce that Bully: Scholarship Edition is coming to the Xbox 360(TM) video game and entertainment system from Microsoft and the Wii(TM) home video game system from Nintendo this Winter. Both the Wii and Xbox 360 versions will retain the wit and deep gameplay of the previously released PlayStation(R)2 computer entertainment system title and will boast additional new content. Bully: Scholarship Edition takes place in the fictional New England boarding school of Bullworth Academy, and tells the story of 15-year-old Jimmy Hopkins as he experiences the highs and lows of adjusting to a new school. Capturing the hilarity and awkwardness of adolescence perfectly, Bully: Scholarship Edition pulls the player into its cinematic and engrossing world. Universally acclaimed upon first release, Bully: Scholarship Edition is a genre-crossing action game with a warmth and pathos that is unrivaled. Bully received a perfect "10/10" from Electronic Gaming Monthly and 1up.com and was heralded as "a great, well-crafted action game that has one of the best senses of humor around" by IGN.com. USA Today called it "a fantastic debut title by Rockstar Vancouver." The San Francisco Chronicle wrote "Bully has no shortage of creative energy, offering an immersive boarding school experience that is imaginative, funny and filled with surprises." Come and explore the zealous joy, mirth, and torment of youth with Jimmy Hopkins and Bully: Scholarship Edition when enrollment commences this Winter.