Zeitschrift Für Kanada-Studien

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gay Pride on Stolen Land: Homonationalism, Queer Asylum

Gay Pride on Stolen Land: Homonationalism, Queer Asylum and Indigenous Sovereignty at the Vancouver Winter Olympics Paper submitted for publication in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies August 2012 Abstract In this paper we examine intersections between homonationalism, sport, gay imperialism and white settler colonialism. The 2010 Winter Olympics, held in Vancouver, Canada, produced new articulations between sporting homonationalism, indigenous peoples and immigration policy. For the first time at an Olympic/Paralympic Games, three Pride Houses showcased LGBT athletes and provided support services for LBGT athletes and spectators. Supporting claims for asylum by queers featured prominently in these support services. However, the Olympic events were held on unceded territories of four First Nations, centered in Vancouver which is a settler colonial city. Thus, we examine how this new form of ‘sporting homonationalism’ emerged upon unceded, or stolen, indigenous land of British Columbia in Canada. Specifically, we argue that this new sporting homonationalism was founded upon white settler colonialism and imperialism—two distinct logics of white supremacy (Smith, 2006).1 Smith explained how white supremacy often functions through contradictory, yet interrelated, logics. We argue that distinct logics of white settler colonialism and imperialism shaped the emergence of the Olympic Pride Houses. On the one hand, the Pride Houses showed no solidarity with the major indigenous protest ‘No Olympics On Stolen Land.’ This absence of solidarity between the Pride Houses and the ‘No Olympics On Stolen Land’ protests reveals how thoroughly winter sports – whether elite or gay events — depend on the logics, and material practices, of white settler colonialism. We analyze how 2 the Pride Houses relied on colonial narratives about ’Aboriginal Participation’ in the Olympics and settler notions of ‘land ownership’. -

Safety in Relationships: Trans Folk

Safety in Relationships Trans Folk Febuary 2020 © 2020 QMUNITY and Legal Services Society, BC Second edition: February 2020 First edition: December 2014 ISBN: 978-1-927661-06-2 (print) ISBN: 978-1-927661-08-6 (online) Published on the traditional unceded territory of the Coast Salish peoples, including the territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and səl̓ ílwətaʔɬ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. Acknowledgements Writer: QMUNITY Editor: Wendy Barron Designer: Caitlan Kuo Legal reviewer: Manjeet Chana Development coordinators: Patricia Lim and QMUNITY Photos: The Gender Spectrum Collection Inside photos: iStock Thanks to a diverse team of volunteers, and to Safe Choices: a LGBT2SQ support and education program of the Ending Violence Association of BC (EVA BC), for their valuable assistance. This publication may not be reproduced commercially, but copying for other purposes, with credit, is encouraged. This booklet explains the law in general. It isn’t intended to give you legal advice on your particular problem. Each person’s case is different. You may need to get legal help. Information in this booklet is up to date as of February 2020. This booklet helps identify what can make a relationship unsafe and provides resources for people looking for support. Caution: This booklet discusses and gives examples of abuse. Consider having someone with you for support, or plan other kinds of self-care, if reading it might make you feel anxious or distressed. An abusive partner might become violent if they find this booklet or see you reading it. For your safety, read it when they’re not around and keep it somewhere they don’t go. -

ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT Report Date: May 9, 2018 Contact: Tim Stevenson Contact No.: 604.873.7247 RTS No.: 12599 Vanrims No.: 08-2

ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT Report Date: May 9, 2018 Contact: Tim Stevenson Contact No.: 604.873.7247 RTS No.: 12599 VanRIMS No.: 08-2000-20 Meeting Date: May 15, 2018 TO: Vancouver City Council FROM: Chief of External Relations and Protocol SUBJECT: Year of the Queer Proclamation and Launch RECOMMENDATION A. THAT in recognition of 15 significant anniversaries celebrated this year by local LGBTTQ organizations, and in recognition of the contributions these organizations have made to Vancouver’s social, cultural and artistic landscape, the City launch a “2018 - Year of the Queer” Proclamation and Launch event. B. THAT Council direct staff to utilize funds designated for the Council approved annual “Pride Week” event at the end of July, and redirect those funds to support a one-time “2018 - Year of the Queer” event at Vancouver City Hall on May 23, 2018. C. THAT Council authorize the 12’ X 24’ Pride Flag and 12’ X 24’ Trans Flag to fly on the north lawn of City Hall from May 23, 2018 – August 19, 2018 as a public acknowledgement of these significant anniversaries. REPORT SUMMARY Vancouver has been enriched by the social, economic, cultural and artistic contributions of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Two-Spirited, Queer (LGBTTQ) community. Twenty-eighteen marks significant anniversaries for 15 local LGBTTQ arts, cultural, community and health organizations, all of which have made substantial contributions to Vancouver’s artistic, social and cultural landscape. In recognition of these anniversaries, it has been recommended that an event at Vancouver City Hall be held from 11 am - 1 pm on Wednesday, May 23 to kick-off the anniversary season on behalf of the celebrating organizations. -

TESIS: Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto Y Contexto En Los Videojuegos Como

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES ACATLÁN Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Tesis para obtener el título de: Licenciado en Comunicación PRESENTA David Mendieta Velázquez ASESOR DE TESIS Mtro. José C. Botello Hernández UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Grand Theft Auto IV Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Agradecimientos A mis padres. Gracias, papá, por enseñarme valores y por tratar de enseñarme todo lo que sabías para que llegara a ser alguien importante. Sé que desde el cielo estás orgulloso de tu familia. Mamá, gracias por todo el apoyo en todos estos años; sé que tu esfuerzo es enorme y en este trabajo se refleja solo un poco de tus desvelos y preocupaciones. Gracias por todo tu apoyo para la terminación de este trabajo. A Ariadna Pruneda Alcántara. Gracias, mi amor, por toda tu ayuda y comprensión. Tu orientación, opiniones e interés que me has dado para la realización de cualquier proyecto que me he propuesto, así como por ser la motivación para seguir adelante siempre. -

El “Crunch” En La Industria De Los Videojuegos

El “crunch” en la industria de los videojuegos Autor: Jesús Moreno Calatayud Tutor: Juan Carlos Redondo Gamero Titulación: Grado en Relaciones Laborales y Recursos Humanos Curso: 2019/2020 ÍNDICE 1. ¿Por qué este trabajo de fin de grado? 2. Objetivos. 3. Marco teórico. a. Tipos de estudios. b. El equipo de desarrollo c. ¿Cuánto cuesta hacer un videojuego? d. Como se hace un videojuego. e. Calendario de lanzamientos. f. Los retrasos. g. ¿Que lleva a un estudio a hacer “crunch”? h. ¿Qué supone trabajar en un estudio de videojuegos? i. ¿Todos los estudios hacen “crunch”? 4. ¿Qué ocurre entonces? a. ¿El Crunch, por qué? b. Las consecuencias y la responsabilidad empresarial. 5. La legislación en cuanto al desarrollo de videojuegos. a. Unión Europea b. España c. Francia d. Reino Unido e. Alemania f. Estados Unidos g. Canadá h. Japón 6. Conclusiones. 7. Bibliografía. 1 2 1 ¿Por qué este trabajo de fin de grado? Desde que era pequeño he crecido en contacto con los videojuegos, siempre me he sentido interesado en el mundo de los videojuegos, he crecido con juegos y he leído de la problemática y la visión negativa que tienen los videojuegos de violentos y otros estereotipos y al mismo tiempo he podido experimentar de propia mano lo erróneo de estos estereotipos. Y ahora, gracias al grado de Relaciones Laborales y Recursos Humanos me he sentido interesado por el contexto laboral de este nuevo mercado, por eso mismo este trabajo de fin de grado es tanto la manera de poner en práctica mucho de lo aprendido como una oportunidad de aprender del mercado de los videojuegos con el que he crecido y relacionarlo con lo que he aprendido durante estos 4 años. -

A Defining Year

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 A DEFINING YEAR QMUNITY at Pride Parade Photo credit: QMUNITY A MESSAGE FROM OUR CHAIR OF THE BOARD AND OUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Over the last 35 years so much has changed. In 1969 we were considered criminals, and pathologized for being queer. In 2014 Laverne Cox, an openly trans, African-American woman, graces the cover of Time Magazine. The world is changing, and our organization continues to change alongside it—yet at our core, the mission remains the same. QMUNITY continues to exist to improve queer and trans lives. QMUNITY Receiving City of Vancouver Award of Excellence for Diversity and Inclusion Diversity for of Excellence Award Vancouver of City Receiving QMUNITY Vancouver of City credit: Photo 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 A MESSAGE FROM OUR CHAIR OF THE BOARD AND OUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Despite the advancement in legal equalities, many people continue to struggle to come out at school, work, or in the home. We are changing that. By ensuring that every single person has an opportunity to feel safe, included, and free from discrimination, we are translating our legal equalities into lived equalities. We know there is still work to be done. In 2014, we reached over 43,000 people, a 23% increase from 2013. We were able to increase our impact by expanding our full-time staff from 8 people to 11 people. This was in large part to our supporters, who helped us increase our budget by 14.6%. But those are just the numbers. Community happens when we celebrate our seniors at the annual Honouring Our Elders Tea, provide 860 hours of free professional counselling, or by advocating for trans friendly schools at the Vancouver School Board. -

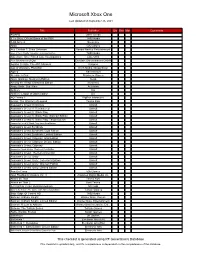

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Interim Report • 1 January – 30 September 2018

THQ NORDIC AB (PUBL) REG NO.: 556582-6558 INTERIM REPORT • 1 JANUARY – 30 SEPTEMBER 2018 EBIT INCREASED 278% TO SEK 90.8 MILLION We had another stable quarter with continued momentum. The strategy of diversification is paying off. Net sales increased by 1,403% to a record SEK 1,272.7 million in the quarter. EBITDA increased by 521% to SEK 214.8 million and EBIT increased by 278% to SEK 90.8 million compared to the same period last year. The gross margin percentage decreased due to a large share of net sales with lower margin within Partner Publishing. Cash flow from operating activities in the quarter was SEK –740.1 million, mainly due to the decision to replace forfaiting of receivables with bank debt within Koch Media. Both THQ Nordic and Koch Media contributed to the group’s EBIT during the quarter. Net sales in the THQ Nordic business area were up 47% to SEK 124.2 million. This was driven by the release of Titan Quest, Red Faction Guerilla Re-Mars-tered and This is the Police 2, in addition to continued performance of Wreckfest. Net sales of Deep Silver were SEK 251.8 million, driven by the release of Dakar 18 and a good performance of Pathfinder Kingmaker at the end of the quarter. The digital net sales of the back-catalogue in both business areas continued to have solid performances. Our Partner Publishing business area had a strong quarter driven by significant releases from our business partners Codemasters, SquareEnix and Sega. During the quarter, we acquired several strong IPs such as Alone in the Dark, Kingdoms of Amalur and Time- splitters. -

Believe Me: Health Equity for Sexual and Gender Diverse Communities

HEALTH EQUITY for SEXUAL AND GENDER DIVERSE COMMUNITIES BELIEVE ME. IDENTIFYING BARRIERS TO HEALTH EQUITY FOR SEXUAL AND GENDER DIVERSE COMMUNITIES IN BRITISH COLUMBIA Reach us at: [email protected] HEC is currently a project of Watari, managed by PeerNetBC. LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT HEC LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We the Sexual and Gender Diversity Health Equity Collaborative (HEC) acknowledge that our work is gathered on unceded traditional homelands of the Coast Salish peoples. The Coast Salish nations are many, and their territories cover a large section of what is otherwise called British Columbia. HEC recognizes that our work is on the traditional, traditional and unceded homelands of the skwx- wú7mesh (Squamish), selílwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh), and xwməθkwəýəm (Musqueam) Nations. Through our five years of work we also recognize the displacement of Indigenous people in their own lands and that our work and gathering of people across the province is taking place on many unnamed traditional and unceded homelands of Indigenous peoples across what is otherwise called British Columbia. We recognize the ongoing very current violence and harm inflicted on Indigenous peoples and their lands. As part of “Health Inequalities and Social Determinants of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health” for the National Collaborating Center for Aboriginal Health, they have included under Distal Determinants of Health the following “Colonialism, Racism and Social Exclusion, Self-Determination”. Each of these has a direct and indirect effect on the Two-Spirit, Sexual and Gender Diverse communitie; they are without a doubt traumatizing for those who live in these communities, and those who have been affected by road blocks. These events have not only had an effect on the Two-Spirit, Sexual and Gender Diverse communities but the rest of Turtle Island as well. -

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Annual Report 2009 DEAR SHAREHOLDERS

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Annual Report 2009 DEAR SHAREHOLDERS, Fiscal year 2009 proved to be a difficult time for • Expanded our presence in Asia, including the our industry and a challenging one for our company. planned release of NBA 2K Online; The economic environment influenced every facet of our sector. Unfavorable market conditions, as well • Completed a $138 million convertible note offering; as several changes in our product release schedule, • Resolved several significant historical legal matters; resulted in a net loss for fiscal year 2009 on net revenue of $968.5 million. • Signed a definitive asset purchase agreement to We remain confident in and committed to sell the Company’s non-core Jack of All Games our strategy of delivering a select portfolio of distribution business; and triple-A, top-rated titles across all key genres and expanding the reach and economic impact of our • Initiated a targeted restructuring of our corporate franchises through new distribution channels and departments to reduce costs and align our territories. Our industry-leading creative talent and resources with our goals. owned intellectual property, coupled with our sound financial position, provides us with the strength and OUR STRATEGY flexibility to build long-term value. Our strategy is to deliver efficiently a limited number of the most creative and innovative titles OUR ACCOMPLISHMENTS in our industry that capture mindshare and market We accomplished a great deal in the past year of share alike. Take-Two’s portfolio encompasses all of which we are very proud, including: today’s key genres, and we’re continually exploring new areas where we can leverage our development • Diversified our industry-leading product portfolio, expertise to expand our audiences across new which will be reflected in our products planned for territories, channels and distribution models. -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

Game Developers Conference Europe Wrap, New Women’S Group Forms, Licensed to Steal Super Genre Break Out, and More

>> PRODUCT REVIEWS SPEEDTREE RT 1.7 * SPACEPILOT OCTOBER 2005 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>POSTMORTEM >>WALKING THE PLANK >>INNER PRODUCT ART & ARTIFICE IN DANIEL JAMES ON DEBUG? RELEASE? RESIDENT EVIL 4 CASUAL MMO GOLD LET’S DEVELOP! Thanks to our publishers for helping us create a new world of video games. GameTapTM and many of the video game industry’s leading publishers have joined together to create a new world where you can play hundreds of the greatest games right from your broadband-connected PC. It’s gaming freedom like never before. START PLAYING AT GAMETAP.COM TM & © 2005 Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. A Time Warner Company. Patent Pending. All Rights Reserved. GTP1-05-116-104_mstrA_v2.indd 1 9/7/05 10:58:02 PM []CONTENTS OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 9 FEATURES 11 TOP 20 PUBLISHERS Who’s the top dog on the publishing block? Ranked by their revenues, the quality of the games they release, developer ratings, and other factors pertinent to serious professionals, our annual Top 20 list calls attention to the definitive movers and shakers in the publishing world. 11 By Tristan Donovan 21 INTERVIEW: A PIRATE’S LIFE What do pirates, cowboys, and massively multiplayer online games have in common? They all have Daniel James on their side. CEO of Three Rings, James’ mission has been to create an addictive MMO (or two) that has the pick-up-put- down rhythm of a casual game. In this interview, James discusses the barriers to distributing and charging for such 21 games, the beauty of the web, and the trouble with executables.