Rhetoric and Wit in Nicolas Bernier's Le Caffé Anne C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY . It seems, however, far more likely that Chopin Notes on the musical text 3 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were intended a different grouping for this figure, e.g.: 7 added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation or . See the Source Commentary. are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an 3 inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, Bar 84 A gentle change of pedal is indicated on the final crotchet pedal indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in order to avoid the clash of g -f. in round brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all the markings in brackets. 2a & 2b. Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9 No. 2 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, (versions with variants) 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small italic numerals , 1 2 3 4 5 . Wherever authentic fingering is enclosed in The sources indicate that while both performing the Nocturne parentheses this means that it was not present in the primary sources, and working on it with pupils, Chopin was introducing more or but added by Chopin to his pupils' copies. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

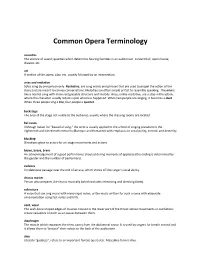

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Music Is Made up of Many Different Things Called Elements. They Are the “I Feel Like My Kind Building Bricks of Music

SECONDARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSIC – BUILDING BRICKS 5 MINUTES READING #1 Music is made up of many different things called elements. They are the “I feel like my kind building bricks of music. When you compose a piece of music, you use the of music is a big pot elements of music to build it, just like a builder uses bricks to build a house. If of different spices. the piece of music is to sound right, then you have to use the elements of It’s a soup with all kinds of ingredients music correctly. in it.” - Abigail Washburn What are the Elements of Music? PITCH means the highness or lowness of the sound. Some pieces need high sounds and some need low, deep sounds. Some have sounds that are in the middle. Most pieces use a mixture of pitches. TEMPO means the fastness or slowness of the music. Sometimes this is called the speed or pace of the music. A piece might be at a moderate tempo, or even change its tempo part-way through. DYNAMICS means the loudness or softness of the music. Sometimes this is called the volume. Music often changes volume gradually, and goes from loud to soft or soft to loud. Questions to think about: 1. Think about your DURATION means the length of each sound. Some sounds or notes are long, favourite piece of some are short. Sometimes composers combine long sounds with short music – it could be a song or a piece of sounds to get a good effect. instrumental music. How have the TEXTURE – if all the instruments are playing at once, the texture is thick. -

Portamento in Romantic Opera Deborah Kauffman

Performance Practice Review Volume 5 Article 3 Number 2 Fall Portamento in Romantic Opera Deborah Kauffman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Kauffman, Deborah (1992) "Portamento in Romantic Opera," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 5: No. 2, Article 3. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.199205.02.03 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol5/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Romantic Ornamentation Portamento in Romantic Opera Deborah Kauffman Present day singing differs from that of the nineteenth century in a num- ber of ways. One of the most apparent is in the use of portamento, the "carrying" of the tone from one note to another. In our own century portamento has been viewed with suspicion; as one author wrote in 1938, it is "capable of much expression when judiciously employed, but when it becomes a habit it is deplorable, because then it leads to scooping."1 The attitude of more recent authors is difficult to ascertain, since porta- mento has all but disappeared as a topic for discussion in more recent texts on singing. Authors seem to prefer providing detailed technical and physiological descriptions of vocal production than offering discussions of style. But even a cursory listening of recordings from the turn of the century reveals an entirely different attitude toward portamento. -

Using Bel Canto Pedagogical Principles to Inform Vocal Exercises Repertoire Choices for Beginning University Singers by Steven M

Using Bel Canto Pedagogical Principles to Inform Vocal Exercises Repertoire Choices for Beginning University Singers by Steven M. Groth B.M. University of Wisconsin, 2013 M.M. University of Missouri, 2017 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts College of Music 2020 1 2 3 Abstract The purpose of this document is to identify and explain the key ideals of bel canto singing and provide reasoned suggestions of exercises, vocalises, and repertoire choices that are readily available both to teachers and students. I provide a critical evaluation of the fundamental tenets of classic bel canto pedagogues, Manuel Garcia, Mathilde Marchesi, and Julius Stockhausen. I then offer suggested exercises to develop breath, tone, and legato, all based classic bel canto principles and more recent insights of voice science and physiology. Finally, I will explore and perform a brief survey into the vast expanse of Italian repertoire that fits more congruently with the concepts found in bel canto singing technique in order to equip teachers with the best materials for more rapid student achievement and success in legato singing. For each of these pieces, I will provide the text and a brief analysis of the characteristics that make each piece well-suited for beginning university students. 4 Acknowledgements Ever since my first vocal pedagogy class in my undergraduate degree at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I have been interested in how vocal pedagogy can best be applied to repertoire choices in order to maximize students’ achievement in the studio environment. -

Williams Legato Digital Piano Will Supply You with Years of Musical Enjoyment If You Follow the Suggestions Listed Below

LEGATO digital piano owner's manual LEGATO DIGITAL PIANO CAUTION: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT REMOVE COVER OR BACK. NO USER-SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED SERVICE PERSONNEL IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS Do not use near water. Clean only with a soft, dry cloth. Do not block any ventilation openings. Do not place near any heat sources such as radiators, heat registers, stoves, or any other apparatus (including amplifiers) that produces heat. Protect the power cord from being walked on or pinched. Only use the included attachments/accessories. Unplug this apparatus during lightning storms or when unused for a long period of time. Refer all servicing to qualified service personnel. Servicing is equiredr when the apparatus has been damaged in any way, such as power-supply cord or plug is damaged, liquid has been spilled or objects have fallen into the apparatus, the apparatus has been exposed to rain or moisture, does not operate normally, or has been dropped. FCC STATEMENTS 1) Caution: Changes or modifications to this unit not expressly approved by the party responsible for compliance could void the user’s authority to operate the equipment. 2) NOTE: This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class B digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference in a residential installation. This equipment generates, uses, and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. -

Choir 6 Grade

Choir 6th Grade Jessica Arnold, Northwest Middle School Vicki Mount, North Middle School Amy Smick, East/Southeast Middle School Matt McClellan – Special Areas Curriculum Coordinator Reviewed by Curriculum Advisory Committee on October 9, 2014 Presented to the Board of Education on December 16, 2014 COURSE TITLE: Choir 6 GRADE LEVEL: 6th CONTENT AREA: Fine Arts Course Description: Students will study vocal techniques, ensemble skills, and basic music theory as related to appropriate music level. Performances are mandatory at the discretion of the teacher. Course Rationale: 6th Grade Choir serves as an introduction to vocal music. Students will develop basic vocal techniques while incorporating the higher order thinking skills of analysis, synthesis, and evaluation in order to have a meaningful musical experience. Course Scope and Sequence Unit 1: Rehearsal and Unit 2: Rhythm Notation and Unit 3: Pitch Notation and Performance Technique Reading Reading (ongoing) (12 weeks) (12 weeks) Unit 4: Road Maps of Unit 5: Dynamics Music/Signs and Symbols (4 weeks) (4 weeks) Unit Objectives: Unit 1: Rehearsals and Performance Technique 1. Students will know the importance of warming up prior to singing. 2. Students will apply techniques to create a quality singing tone. 3. Students will apply the concept of balance and blend across a choral ensemble. 4. Students will sing 2‐part music in the choral setting. 5. Students will sing using the appropriate expression for the context of the selected piece. 6. Students will display appropriate concert etiquette on stage and in the audience. Unit 2: Rhythm Notation and Reading 1. Students will know basic vocabulary regarding rhythmic notation, including staff, time signature, barline, measure, and double barline. -

THE MESSA DI VOCE and ITS EFFECTIVENESS AS a TRAINING EXERCISE for the YOUNG SINGER D. M. A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfi

THE MESSA DI VOCE AND ITS EFFECTIVENESS AS A TRAINING EXERCISE FOR THE YOUNG SINGER D. M. A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Diane M. Pulte, B.M., M.M. *** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Karen Peeler Approved by Dr. C. Patrick Woliver ______________ Adviser Dr. Michael Trudeau School of Music ABSTRACT The Messa di voce and Its Effectiveness as a Training Device for the Young Singer This document is a study of the traditional Messa di voce exercise (“placing of the voice”) and it’s effectiveness as a teaching tool for the young singer. Since the advent of Baroque music the Messa di voce has not only been used as a dynamic embellishment in performance practice, but also as a central vocal teaching exercise. It gained special prominence during the 19th and early 20th century as part of the so-called Bel Canto technique of singing. The exercise demonstrates a delicate balance between changing sub-glottic aerodynamic pressures and fundamental frequency, while consistently producing a voice of optimal singing quality. The Messa di voce consists of the controlled increase and subsequent decrease in intensity of tone sustained on a single pitch during one breath. An early definition of the Messa di voce can be found in Instruction Of Mr. Tenducci To His Scholars by Guisto Tenducci (1785): To sing a messa di voce: swelling the voice, begin pianissimo and increase gradually to forte, in the first part of the time: and so diminish gradually to the end of each note, if possible. -

Ventus Series: Tin Whistle

Ventus Series: Tin Whistle An Impact Soundworks Library Designed by Constructive Stumblings | Performed by Josh Plotner Scripted by Nabeel Ansari and Andrew Aversa Instrument v1.00 OVERVIEW Our Ventus Series of ethnic woodwind instruments began with the Japanese Shakuhachi, and continues in this installment with a journey to Europe and the wonderful Tin Whistle, most closely associated with the Emerald Isle itself - Ireland. This gorgeous instrument, a type of recorder, has origins dating back tens of thousands of years and has found its place squarely in the heart of Celtic music among other things. Its pure tone is also instantly recognizable in some of the most beloved soundtracks of all time, such as Howard Shore’s score to the Lord of the Rings film trilogy. Much like the Ventus Shakuhachi, our Tin Whistle is sampled in meticulous depth with a wide variety of articulations, ornaments, and phrases to inspire your music and creativity. Use it for soaring, agile solo performances or slow, flowing and emotive parts; it works just as well! Of course, the instrument also includes our Total Articulation Control Technology (TACT), unifying and simplifying the process of creating your own personal mapping setup for the instrument. We hope you enjoy our Ventus Series Tin Whistle! INSTALLATION 1. Install the Pulse application if you don’t already have it. Pulse is a cross-platform desktop app that lets you download and install your libraries with blazing speed! https://pulsedownloader.com/ 2. Once Pulse is installed, open it and enter your Ventus Tin Whistle download code. Follow the instructions to download and install the library. -

Legato-Essay

L E G A T O I a m o f t e n a s k e d i f l e g a t o a n d p o r t a m e n t o a r e t h e s a m e t h i n g : t h e y a r e n o t . L E G A T O i s a m u s i c a l t e r m m e a n i n g " s m o o t h l y b o u n d t o g e t h e r w i t h o u t b r e a k s b e t w e e n t h e n o t e s . ” P O R T A M E N T O i s t h e t o o l a s i n g e r u s e s t o a c h i e v e t h i s . A lot of confusion stems from the fact that legato is achieved in different ways on different instruments. The pianist for example has 10 fingers and a right foot to achieve it. Simply put, a pianist can depress key B before releasing key A to achieve finger legato. He can also use the sustaining pedal to “bind notes together” if the fingers cannot reach. Well, singers cannot sing two notes at the same time and have no pedal! The string player can put down a second finger on the fingerboard before picking up the first one.