Rhapsody Ossia Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång Till

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång till Lotta, Jan Sandström. Edition Tarrodi: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. Trombone and piano. Requires modest range (F – g flat1), well-developed lyricism, and musicianship. There are two versions of this piece, this and another that is scored a minor third higher. Written dynamics are minimal. Although phrases and slurs are not indicated, it is a SONG…encourage legato tonguing! Stephan Schulz, bass trombonist of the Berlin Philharmonic, gives a great performance of this work on YouTube - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mn8569oTBg8. A Winter’s Night, Kevin McKee, 2011. Available from the composer, www.kevinmckeemusic.com. Trombone and piano. Explores the relative minor of three keys, easy rhythms, keys, range (A – g1, ossia to b flat1). There is a fine recording of this work on his web site. Trombone Sonata, Gordon Jacob. Emerson Edition: Yorkshire, England, 1979. Trombone and piano. There are no real difficult rhythms or technical considerations in this work, which lasts about 7 minutes. There is tenor clef used throughout the second movement, and it switches between bass and tenor in the last movement. Range is F – b flat1. Recorded by Dr. Ron Babcock on his CD Trombone Treasures, and available at Hickey’s Music, www.hickeys.com. Divertimento, Edward Gregson. Chappell Music: London, 1968. Trombone and piano. Three movements, range is modest (G-g#1, ossia a1), bass clef throughout. Some mixed meter. Requires a mute, glissandi, and ad. lib. flutter tonguing. Recorded by Brett Baker on his CD The World of Trombone, volume 1, and can be purchased at http://www.brettbaker.co.uk/downloads/product=download-world-of-the- trombone-volume-1-brett-baker. -

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY . It seems, however, far more likely that Chopin Notes on the musical text 3 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were intended a different grouping for this figure, e.g.: 7 added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation or . See the Source Commentary. are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an 3 inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, Bar 84 A gentle change of pedal is indicated on the final crotchet pedal indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in order to avoid the clash of g -f. in round brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all the markings in brackets. 2a & 2b. Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9 No. 2 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, (versions with variants) 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small italic numerals , 1 2 3 4 5 . Wherever authentic fingering is enclosed in The sources indicate that while both performing the Nocturne parentheses this means that it was not present in the primary sources, and working on it with pupils, Chopin was introducing more or but added by Chopin to his pupils' copies. -

Studio N. 114-2020/C

Consiglio Nazionale del Notariato Studio n.114-2020/C IL CONTENUTO ATIPICO DEL TESTAMENTO di Vincenzo Barba (Approvato dalla Commissione Studi Civilistici il 13 ottobre 2020) Abstract Lo studio, movendo da una analisi storica della nozione di testamento intende dimostrare le sue straordinarie potenzialità, precisando che non è l’unico atto di ultima volontà. Si chiarisce che con il testamento la persona può regolare non solo i suoi interessi patrimoniali, ma anche tutti gli interessi non patrimoniali, anche oltre i casi previsti dalla legge. La distinzione tra contenuto tipico e atipico del testamento è servita storicamente per distinguere tra disposizioni patrimoniali e no; essa tuttavia non può servire, nella contemporaneità, né per definire il concetto di testamento, né per individuare la disciplina applicabile. Questa distinzione non serve per escludere la rilevanza testamentaria della regolamentazione degli interessi non patrimoniali, ma per affermare la possibilità di regolamentare questi interessi non soltanto con il testamento, ma anche con l’atto di ultima volontà, diverso dal testamento. Leggendo insieme gli artt. 587 e 588 Cod. civ. non può dirsi che il testamento è limitato al contenuto attributivo, ossia quello che si risolve nell’istituzione di erede o nel legato, ma che il testamento è l’atto regolativo della successione a causa di morte della persona e che al solo testamento è riservata la possibilità di contenere istituzioni di erede o di legato. Con intesa che tutti gli altri profili successori della persona e, in specie quelli non patrimoniali, e comunque, quelli non incidenti sulla delazione possono essere regolati anche con atti di ultima volontà diversi dal testamento, la cui forma deve essere valutata, salvo che non sia espressamente preveduta dalla legge, in ragione degli interessi che l’atto compone e della sua funzione. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

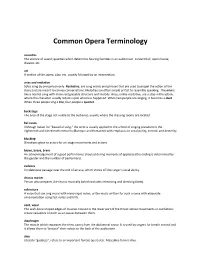

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Kenneth E. Querns Langley Doctor of Philosophy

Reconstructing the Tenor ‘Pharyngeal Voice’: a Historical and Practical Investigation Kenneth E. Querns Langley Submitted in partial fulfilment of Doctor of Philosophy in Music 31 October 2019 Page | ii Abstract One of the defining moments of operatic history occurred in April 1837 when upon returning to Paris from study in Italy, Gilbert Duprez (1806–1896) performed the first ‘do di petto’, or high c′′ ‘from the chest’, in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell. However, according to the great pedagogue Manuel Garcia (jr.) (1805–1906) tenors like Giovanni Battista Rubini (1794–1854) and Garcia’s own father, tenor Manuel Garcia (sr.) (1775–1832), had been singing the ‘do di petto’ for some time. A great deal of research has already been done to quantify this great ‘moment’, but I wanted to see if it is possible to define the vocal qualities of the tenor voices other than Duprez’, and to see if perhaps there is a general misunderstanding of their vocal qualities. That investigation led me to the ‘pharyngeal voice’ concept, what the Italians call falsettone. I then wondered if I could not only discover the techniques which allowed them to have such wide ranges, fioritura, pianissimi, superb legato, and what seemed like a ‘do di petto’, but also to reconstruct what amounts to a ‘lost technique’. To accomplish this, I bring my lifelong training as a bel canto tenor and eighteen years of experience as a classical singing teacher to bear in a partially autoethnographic study in which I analyse the most important vocal treatises from Pier Francesco Tosi’s (c. -

Gli Esiliati in Siberia, Exile, and Gaetano Donizetti Alexander Weatherson

Gli esiliati in Siberia, exile, and Gaetano Donizetti Alexander Weatherson How many times did Donizetti write or rewrite Otto mesi in due ore. No one has ever been quite sure: at least five times, perhaps seven - it depends how the changes he made are viewed. Between 1827 and 1845 he set and reset the music of this strange but true tale of heroism - of the eighteen-year-old daughter who struggled through snow and ice for eight months to plead with the Tsar for the release of her father from exile in Siberia, making endless changes - giving it a handful of titles, six different poets supplying new verses (including the maestro himself), with- and-without spoken dialogue, with-and-without Neapolitan dialect, with-and-without any predictable casting (the prima donna could be a soprano, mezzo-soprano or contralto at will), and with-and-without any very enduring resolution at the end so that this extraordinary work has an even-more-fantastic choice of synopses than usual. It was this score that stayed with him throughout his years of international fame even when Lucia di Lammermoor and Don Pasquale were taking the world by storm. It is perfectly possible in fact that the music of his final revision of Otto mesi in due ore was the very last to which he turned his stumbling hand before mental collapse put an end to his hectic career. How did it come by its peculiar title? In 1806 Sophie Cottin published a memoir in London and Paris of a real-life Russian heroine which she called 'Elisabeth, ou Les Exilés de Sibérie'. -

Music Is Made up of Many Different Things Called Elements. They Are the “I Feel Like My Kind Building Bricks of Music

SECONDARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSIC – BUILDING BRICKS 5 MINUTES READING #1 Music is made up of many different things called elements. They are the “I feel like my kind building bricks of music. When you compose a piece of music, you use the of music is a big pot elements of music to build it, just like a builder uses bricks to build a house. If of different spices. the piece of music is to sound right, then you have to use the elements of It’s a soup with all kinds of ingredients music correctly. in it.” - Abigail Washburn What are the Elements of Music? PITCH means the highness or lowness of the sound. Some pieces need high sounds and some need low, deep sounds. Some have sounds that are in the middle. Most pieces use a mixture of pitches. TEMPO means the fastness or slowness of the music. Sometimes this is called the speed or pace of the music. A piece might be at a moderate tempo, or even change its tempo part-way through. DYNAMICS means the loudness or softness of the music. Sometimes this is called the volume. Music often changes volume gradually, and goes from loud to soft or soft to loud. Questions to think about: 1. Think about your DURATION means the length of each sound. Some sounds or notes are long, favourite piece of some are short. Sometimes composers combine long sounds with short music – it could be a song or a piece of sounds to get a good effect. instrumental music. How have the TEXTURE – if all the instruments are playing at once, the texture is thick. -

Don Giovanni Press Release 10.9.18

For Immediate Release October 9, 2018 Contact: Lana Sadowski, Director of Marketing, Hampton Roads P.O. BOX 2580 ● Norfolk, VA 23501 PHONE: 757.627.9545 X 3316 EMAIL: [email protected] Virginia Opera Presents W.A. Mozart’s Don Giovanni Tale of Merciless Seducer Returns in Sixth Company Production: Performances Statewide November 2–18 Hampton Roads, Richmond, Fairfax, Virginia (October 9, 2018) — As the second opera production in its 44th season, Virginia Opera announces a new production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s ever-popular opera Don Giovanni. Statewide performances begin November 2, and conclude November 18, 2018 (please see complete list of venue locations and dates below). First performed in 1787 as Il dissoluto punito ossia il Don Giovanni (The rake punished also Don Giovan- ni), Mozart’s two-act opera traces the storied tale of the merciless seducer Don Juan in what has be- come one of the top ten most globally performed and timeless morality tales in operatic history. Come- dy and tragedy intermingle in ways only supernatural forces can address in the narrative of the legend- ary Spanish nobleman’s compulsive and destructive amorous conquests, leaving his ultimate fate in the hands of demons from the underworld as it reminds audiences that even those most powerful cannot avoid the consequences of their actions. Virginia Opera’s 2018 production of Don Giovanni represents the sixth time the company has ap- proached the classic—the last occurring in 2010—and, with it, acclaimed director Lillian Groag’s 24th VO production. Groag’s beloved veteran status is bookended by the exciting collection of emerging vocal talents making VO company debuts within the production. -

Portamento in Romantic Opera Deborah Kauffman

Performance Practice Review Volume 5 Article 3 Number 2 Fall Portamento in Romantic Opera Deborah Kauffman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Kauffman, Deborah (1992) "Portamento in Romantic Opera," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 5: No. 2, Article 3. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.199205.02.03 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol5/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Romantic Ornamentation Portamento in Romantic Opera Deborah Kauffman Present day singing differs from that of the nineteenth century in a num- ber of ways. One of the most apparent is in the use of portamento, the "carrying" of the tone from one note to another. In our own century portamento has been viewed with suspicion; as one author wrote in 1938, it is "capable of much expression when judiciously employed, but when it becomes a habit it is deplorable, because then it leads to scooping."1 The attitude of more recent authors is difficult to ascertain, since porta- mento has all but disappeared as a topic for discussion in more recent texts on singing. Authors seem to prefer providing detailed technical and physiological descriptions of vocal production than offering discussions of style. But even a cursory listening of recordings from the turn of the century reveals an entirely different attitude toward portamento.