Wet Phases in the Sahara/Sahel Region and Human Migration Patterns in North Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i: Nā Makani

November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai‘i: Nā Makani Mau Steven Businger & Sara da Silva [email protected], [email protected] Iasona Ellinwood, [email protected] Pauline W. U. Chinn, [email protected] University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Figure 1. Schematic of global circulation Grades: 6-8, modifiable for 9-12 Time: 2 - 10 hours Nā Honua Mauli Ola, Guidelines for Educators, No Nā Kumu: Educators are able to sustain respect for the integrity of one’s own cultural knowledge and provide meaningful opportunities to make new connections among other knowledge systems (p. 37). Standard: Earth and Space Science 2.D ESS2D: Weather and Climate Weather varies day to day and seasonally; it is the condition of the atmosphere at a given place and time. Climate is the range of a region’s weather over one to many years. Both are shaped by complex interactions involving sunlight, ocean, atmosphere, latitude, altitude, ice, living things, and geography that can drive changes over multiple time scales—days, weeks, and months for weather to years, decades, centuries, and beyond for climate. The ocean absorbs and stores large amounts of energy from the sun and releases it slowly, moderating and stabilizing global climates. Sunlight heats the land more rapidly. Heat energy is redistributed through ocean currents and atmospheric circulation, winds. Greenhouse gases absorb and retain the energy radiated from land and ocean surfaces, regulating temperatures and keep Earth habitable. (A Framework for K-12 Science Education, NRC, 2012) Hawai‘i Content and Performance Standards (HCPS) III http://standardstoolkit.k12.hi.us/index.html 1 November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i STRAND THE SCIENTIFIC PROCESS Standard 1: The Scientific Process: SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION: Discover, invent, and investigate using the skills necessary to engage in the scientific process Benchmarks: SC.8.1.1 Determine the link(s) between evidence and the Topic: Scientific Inquiry conclusion(s) of an investigation. -

Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2019-07-01 Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA Natalie Shepherd Barkdull Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Barkdull, Natalie Shepherd, "Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 8590. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8590 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA Natalie Shepherd Barkdull A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Gregory T. Carling, Chair Barry R. Bickmore Stephen T. Nelson Department of Geological Sciences Brigham Young University Copyright © 2019 Natalie Shepherd Barkdull All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Impacts of Glacial Meltwater on Geochemistry and Discharge of Alpine Proglacial Streams in the Wind River Range, Wyoming, USA Natalie Shepherd Barkdull Department of Geological Sciences, BYU Master of Science Shrinking alpine glaciers alter the geochemistry of sensitive mountain streams by exposing reactive freshly-weathered bedrock and releasing decades of atmospherically-deposited trace elements from glacier ice. Changes in the timing and quantity of glacial melt also affect discharge and temperature of alpine streams. -

The Generation of Mega Glacial Meltwater Floods and Their Geologic

urren : C t R gy e o s l e o r a r LaViolette, Hydrol Current Res 2017, 8:1 d c y h H Hydrology DOI: 10.4172/2157-7587.1000269 Current Research ISSN: 2157-7587 Research Article Open Access The Generation of Mega Glacial Meltwater Floods and Their Geologic Impact Paul A LaViolette* The Starburst Foundation, 1176 Hedgewood Lane, Niskayuna, New York 12309, United States Abstract A mechanism is presented explaining how mega meltwater avalanches could be generated on the surface of a continental ice sheet. It is shown that during periods of excessive climatic warmth when the continental ice sheet surface was melting at an accelerated rate, self-amplifying, translating waves of glacial meltwater emerge as a distinct mechanism of meltwater transport. It is shown that such glacier waves would have been capable of attaining kinetic energies per kilometer of wave front equivalent to 12 million tons of TNT, to have achieved heights of 100 to 300 meters, and forward velocities as great as 900 km/hr. Glacier waves would not have been restricted to a particular locale, but could have been produced wherever continental ice sheets were present. Catastrophic floods produced by waves of such size and kinetic energy would be able to account for the character of the permafrost deposits found in Alaska and Siberia, flood features and numerous drumlin field formations seen in North America, and many of the lignite deposits found in Europe, Siberia, and North America. They also could account for how continental debris was transported thousands of kilometers into the mid North Atlantic to form Heinrich layers. -

Freshwater Resources

3 Freshwater Resources Coordinating Lead Authors: Blanca E. Jiménez Cisneros (Mexico), Taikan Oki (Japan) Lead Authors: Nigel W. Arnell (UK), Gerardo Benito (Spain), J. Graham Cogley (Canada), Petra Döll (Germany), Tong Jiang (China), Shadrack S. Mwakalila (Tanzania) Contributing Authors: Thomas Fischer (Germany), Dieter Gerten (Germany), Regine Hock (Canada), Shinjiro Kanae (Japan), Xixi Lu (Singapore), Luis José Mata (Venezuela), Claudia Pahl-Wostl (Germany), Kenneth M. Strzepek (USA), Buda Su (China), B. van den Hurk (Netherlands) Review Editor: Zbigniew Kundzewicz (Poland) Volunteer Chapter Scientist: Asako Nishijima (Japan) This chapter should be cited as: Jiménez Cisneros , B.E., T. Oki, N.W. Arnell, G. Benito, J.G. Cogley, P. Döll, T. Jiang, and S.S. Mwakalila, 2014: Freshwater resources. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 229-269. 229 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ 232 3.1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Himalayan Glaciers

Himalayan Glaciers Climate Change, Water Resources, and Water Security Scientific evidence shows that most glaciers in South Asia’s Hindu Kush Himalayan region are retreating, but the consequences for the region’s water supply are unclear, this report finds. The Hindu Kush Himalayan region is the location of several of Asia’s great river systems, which provide water for drinking, irrigation, and other uses for about 1.5 billion people. Recent studies show that at lower elevations, glacial retreat is unlikely to cause significant changes in water availability over the next several decades, but other factors, including groundwater depletion and increasing human water use, could have a greater impact. Higher elevation areas could experience altered water flow in some river basins if current rates of glacial retreat continue, but shifts in the location, intensity, and variability of rain and snow due to climate change will likely have a greater impact on regional water supplies. he Himalayan region, which Tcovers eight countries across Asia, is home to some of the world’s largest and most spectacular glaciers. The melt- water generated from these glaciers each summer supplements the rivers and streams of the region, including several of Asia’s great river systems such as the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra. Rising tempera- tures due to climate change are causing glaciers worldwide to Figure 1. Extending over 2000 kilometers across the Asian continent and including all shrink in volume and or part of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan, the mass, a phenomenon Hindu Kush Himalayan region is the source for many of Asia’s major river systems, known as glacial including the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra. -

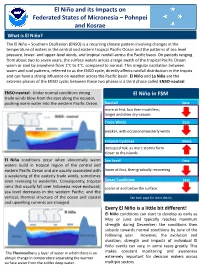

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei and Kosrae What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones More increased risk, as more storms form closer to the islands El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

The Potential of Hudson Valley Glacial Floods to Drive Abrupt Climate Change

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00228-1 OPEN The potential of Hudson Valley glacial floods to drive abrupt climate change ✉ Simon Pendleton 1 , Alan Condron 1 & Jeffrey Donnelly1 The periodic input of meltwater into the ocean from a retreating Laurentide Ice Sheet is often hypothesized to have weakened the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) and triggered several cold periods during the last deglaciation (21,000 to 8,000 years before present). Here, we use a numerical model to investigate whether the Intra-Allerød Cold Period was triggered by the drainage of Glacial Lake Iroquois, ~13,300 years ago. Performing a large suite of experiments with various combinations of single and successive, short fl fi fi 1234567890():,; (1 month) and long (1 year) duration ood events, we were unable to nd any signi cant weakening of the AMOC. This result suggests that although the Hudson Valley floods occurred close to the beginning of the Intra-Allerød Cold Period, they were unlikely the sole cause. Our results have implications for re-evaluating the relationship of meltwater flood events (past and future) to periods of climatic cooling, particularly with regards to flood input location, volume, frequency, and duration. ✉ 1 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA. email: [email protected] COMMUNICATIONS EARTH & ENVIRONMENT | (2021) 2:152 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00228-1 | www.nature.com/commsenv 1 ARTICLE COMMUNICATIONS EARTH & ENVIRONMENT | https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00228-1 n the late 1980s periodic meltwater inputs from a retreating supports a second larger flood (~2500 km3) then drained the ILaurentide Ice Sheet (LIS) were hypothesized to have hindered successor to Lake Iroquois, Lake Frontenac, along with the glacial North Atlantic deep water (NADW) formation, leading to a lake in the Champlain Valley (Lake Fort Ann) down the Hudson weakened Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), River9–12 (Fig. -

Origin of the First Global Meltwater Pulse Following the Last Glacial Maximum

PALEOCEANOGRAPHY, VOL. 11, NO. 5, PAGES 563-577, OCTOBER 1996 Origin of the first global meltwater pulse following the last glacial maximum PeterU. Clark,l Richard B. Alley, 2Lloyd D. Keigwin,3Joseph M. Licciardi,• SigfusJ.Johnsen, 4'•and Huaxiao Wang 6 Abstract. Well-datedsea level recordsshow that the glacioeustaticrise followingthe lastglacial maximumwas characterizedby two or possiblythree brief intervalsof rapid sealevel rise separat- ing periodswith muchlower rates. Thesevery highrates of sealevel rise indicate periods of ex- ceptionallyrapid deglaciation of remainingice sheets.The LaurentideIce Sheetis commonlytar- getedas the sourceof the first, andlargest, of the meltwaterpulses (mwp-IA between-14,200 (12,200•4C years B.P.) and 13,700 years ago (11,700 •4C years B.P.)). In alloceanic records of deglaciationof the formernorthern hemisphere ice sheetsthat we review, only thosefrom the Gulfof Mexico and the Bermuda Rise show evidence oflow ;5•80 values at the time of mwp-IA, identifyingthe southernLaurentide Ice Sheetas a potentialsource for mwp-IA. We questionthis sourcefor mwp-IA, however,because (1) ice sheetmodels suggest that this sectorof the ice sheet contributedonly a fraction(<10%) of the sealevel needed for mwp-IA, (2) meltingthis sector of the ice sheetat the necessaryrate to explainmwp-IA is physicallyimplausible, and (3) ocean modelspredict a muchstronger thermohaline response to theinferred freshwater pulse out of the MississippiRiver into theNorth Atlanticthan is recorded.This leavesthe AntarcticIce Sheetas the only -

The Wind-Wave Climate of the Pacific Ocean

The Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research A partnership between CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology The wind-wave climate of the Pacific Ocean. Mark Hemer, Jack Katzfey and Claire Hotan Final Report 30 September 2011 Report for the Pacific Adaptation Strategy Assistance Program Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency [Insert ISBN or ISSN and Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) information here if required] Enquiries should be addressed to: Mark Hemer Email. [email protected] Distribution list DCCEE 1 Copyright and Disclaimer © 2011 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Important Disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. Contents -

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Yap And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Yap and Chuuk What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then very much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones Less reduced risk, as more storms form closer to the Dateline El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

City of Homer Stormwater and Meltwater

Stormwater aaandand Meltwater Management aaandand Mitigation A Handbook for Homer, Alaska .. 2 Homer Stormwater and Meltwater Management and Mitigation A Handbook for Homer, Alaska 2007 City of Homer, Alaska Allegra Bukojemsky, RLA David Scheer, MArch This handbook was created by Allegra Bukojemsky and David Scheer, of DnA Design. The authors may be contracted for future modifications or edits. In no way is the use of the authors’ names condoned for the authorship of future texts without consent All figures and images are by the authors unless otherwise noted. Stormwater Manual i ii Homer Table of Contents Introduction page 1 Chapter 1: Stormwater - An overview page 3 Key Term Definitions Hydrologic cycle Watershed The Hydrograph Development Streams and Lakes Water quality Wetlands and Riparian Areas Plants & Soils Shore and Bluff Infrastructure and Maintenance Regulations – public influence over public effects Stormwater specifics in Homer Chapter 2: Site planning for stormwater management page 12 Site Design – Retain important site function Preserve wetlands and riparian areas Use established vegetation & soils Site Design – Strategies for an effective Site Plan Limit impervious surface area Limit connections between impervious surface Slow runoff and dissipate energy Design a sensitive grading plan Maintain connections beyond your property Site design – Cold climate considerations Freezing – winter conditions Snow Storage and Spring Melt considerations Site Design – Other considerations Siting of constructed stormwater management systems -

Tropical Cyclone Part II (1+1+1 System) Geography Hons

Tropical Cyclone Part II (1+1+1 System) Geography Hons. Paper: IV Module: V Topic: 4.1 A tropical cyclone is a system of the low pressure area surrounded by high pressure areas on all sides occurring in tropical zone bound by Tropic of Cancer in the north and Tropic of Capricorn in the south. Chief Characteristics of Tropical Cyclones 1. Tropical cyclones are of numerous forms which vary considerably in shape, size and weather conditions. 2. There are wide variations in the size of the tropical cyclones. However, the average diameter of a tropical cyclone varies from 80 to 300 km. Some of the cyclones have diameter of only 50 km or even less than that. 3. The isobars in most tropical cyclones are generally circular, indicating that most of the tropical cyclones are circular in shape. 4. The isobars are closely spaced which indicates that the pressure gradient is very steep and winds blow at high speed. 5. Most of the tropical cyclones originate on the western margins of the oceans where warm ocean currents maintain sea surface temperature above 27°C. 6. They advance with varying velocities and their velocities depend upon a number of factors. Weak cyclones move at velocities varying from 30 to 35 km/hr. while hurricanes may attain velocity of 180 km/hr. or even more. 7. They are very vigorous and move with high speed over the oceans where there are no obstructions in their way. 8. They are more frequent in late summer and autumn in the Northern Hemisphere and spring in the Southern Hemisphere.