Trade Winds Weaken Over the Atlantic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i: Nā Makani

November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai‘i: Nā Makani Mau Steven Businger & Sara da Silva [email protected], [email protected] Iasona Ellinwood, [email protected] Pauline W. U. Chinn, [email protected] University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Figure 1. Schematic of global circulation Grades: 6-8, modifiable for 9-12 Time: 2 - 10 hours Nā Honua Mauli Ola, Guidelines for Educators, No Nā Kumu: Educators are able to sustain respect for the integrity of one’s own cultural knowledge and provide meaningful opportunities to make new connections among other knowledge systems (p. 37). Standard: Earth and Space Science 2.D ESS2D: Weather and Climate Weather varies day to day and seasonally; it is the condition of the atmosphere at a given place and time. Climate is the range of a region’s weather over one to many years. Both are shaped by complex interactions involving sunlight, ocean, atmosphere, latitude, altitude, ice, living things, and geography that can drive changes over multiple time scales—days, weeks, and months for weather to years, decades, centuries, and beyond for climate. The ocean absorbs and stores large amounts of energy from the sun and releases it slowly, moderating and stabilizing global climates. Sunlight heats the land more rapidly. Heat energy is redistributed through ocean currents and atmospheric circulation, winds. Greenhouse gases absorb and retain the energy radiated from land and ocean surfaces, regulating temperatures and keep Earth habitable. (A Framework for K-12 Science Education, NRC, 2012) Hawai‘i Content and Performance Standards (HCPS) III http://standardstoolkit.k12.hi.us/index.html 1 November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i STRAND THE SCIENTIFIC PROCESS Standard 1: The Scientific Process: SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION: Discover, invent, and investigate using the skills necessary to engage in the scientific process Benchmarks: SC.8.1.1 Determine the link(s) between evidence and the Topic: Scientific Inquiry conclusion(s) of an investigation. -

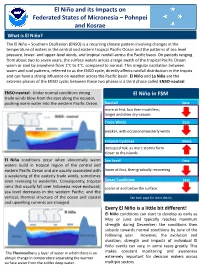

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei and Kosrae What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones More increased risk, as more storms form closer to the islands El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

The Wind-Wave Climate of the Pacific Ocean

The Centre for Australian Weather and Climate Research A partnership between CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology The wind-wave climate of the Pacific Ocean. Mark Hemer, Jack Katzfey and Claire Hotan Final Report 30 September 2011 Report for the Pacific Adaptation Strategy Assistance Program Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency [Insert ISBN or ISSN and Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) information here if required] Enquiries should be addressed to: Mark Hemer Email. [email protected] Distribution list DCCEE 1 Copyright and Disclaimer © 2011 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Important Disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. Contents -

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Yap And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Yap and Chuuk What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then very much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones Less reduced risk, as more storms form closer to the Dateline El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

Tropical Cyclone Part II (1+1+1 System) Geography Hons

Tropical Cyclone Part II (1+1+1 System) Geography Hons. Paper: IV Module: V Topic: 4.1 A tropical cyclone is a system of the low pressure area surrounded by high pressure areas on all sides occurring in tropical zone bound by Tropic of Cancer in the north and Tropic of Capricorn in the south. Chief Characteristics of Tropical Cyclones 1. Tropical cyclones are of numerous forms which vary considerably in shape, size and weather conditions. 2. There are wide variations in the size of the tropical cyclones. However, the average diameter of a tropical cyclone varies from 80 to 300 km. Some of the cyclones have diameter of only 50 km or even less than that. 3. The isobars in most tropical cyclones are generally circular, indicating that most of the tropical cyclones are circular in shape. 4. The isobars are closely spaced which indicates that the pressure gradient is very steep and winds blow at high speed. 5. Most of the tropical cyclones originate on the western margins of the oceans where warm ocean currents maintain sea surface temperature above 27°C. 6. They advance with varying velocities and their velocities depend upon a number of factors. Weak cyclones move at velocities varying from 30 to 35 km/hr. while hurricanes may attain velocity of 180 km/hr. or even more. 7. They are very vigorous and move with high speed over the oceans where there are no obstructions in their way. 8. They are more frequent in late summer and autumn in the Northern Hemisphere and spring in the Southern Hemisphere. -

Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania

13 · Nautical Cartography and Traditional Navigation in Oceania BEN FINNEY MENTAL CARTOGRAPHY formal images and their own sense perceptions to guide their canoes over the ocean. The navigational practices of Oceanians present some The idea of physically portraying their mental images what of a puzzle to the student of the history of carto was not alien to these specialists, however. Early Western graphy. Here were superb navigators who sailed their ca explorers and missionaries recorded instances of how in noes from island to island, spending days or sometimes digenous navigators, when questioned about the islands many weeks out of sight of land, and who found their surrounding their own, readily produced maps by tracing way without consulting any instruments or charts at sea. lines in the sand or arranging pieces of coral. Some of Instead, they carried in their head images of the spread of these early visitors drew up charts based on such ephem islands over the ocean and envisioned in the mind's eye eral maps or from information their informants supplied the bearings from one to the other in terms of a con by word and gesture on the bearing and distance to the ceptual compass whose points were typically delineated islands they knew. according to the rising and setting of key stars and con Furthermore, on some islands master navigators taught stellations or the directions from which named winds their pupils a conceptual "star compass" by laying out blow. Within this mental framework of islands and bear coral fragments to signify the rising and setting points of ings, to guide their canoes to destinations lying over the key stars and constellations. -

African Humid Period'' and the Record of Marine Upwelling from Excess Th

PALEOCEANOGRAPHY, VOL. 21, PA4203, doi:10.1029/2005PA001200, 2006 Click Here for Full Article The ‘‘African humid period’’ and the record of marine upwelling from excess 230Th in Ocean Drilling Program Hole 658C Jess Adkins,1 Peter deMenocal,2 and Gidon Eshel3 Received 26 August 2005; revised 4 February 2006; accepted 13 June 2006; published 20 October 2006. 230 [1] Using a high-resolution Th normalized record of sediment flux, we document the deglacial and Holocene history of North African aridity and coastal upwelling at Ocean Drilling Program Hole 658C. At both the end of the Younger Dryas and after the 8.2 ka event, there are significant drops in terrigenous accumulation at our site, indicating an increase in the monsoon moisture flux over Africa at this time. At 5.5 ka, there is an abrupt end to the ‘‘African humid period’’ and a return to stronger upwelling conditions. For carbonate and opal fluxes the 230Th normalization completely changes the shape of each record based on percentage variations alone. This site is a clear example of how variations in one sediment component can obscure changes in the others, and it demonstrates the need for radionuclide measurements more generally in paleoceanography. By taking our new records and a large amount of previous data from this site we conclude that increases in African moisture are tightly coupled to decreases in coastal upwelling intensity. Citation: Adkins, J., P. deMenocal, and G. Eshel (2006), The ‘‘African humid period’’ and the record of marine upwelling from excess 230Th in Ocean Drilling Program Hole 658C, Paleoceanography, 21, PA4203, doi:10.1029/2005PA001200. -

Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (Pp

Chapter 7 - Title Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (pp. 165-195) Contents • scales of motion and turbulence • local winds • the General Circulation of the atmosphere • ocean currents Wind Examples Fig. 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion. Microscale → mesoscale → synoptic scale. Scales of Motion • Microscale – e.g. chimney – Short lived ‘eddies’, chaotic motion – Timescale: minutes • Mesoscale – e.g. local winds, thunderstorms – Timescale mins/hr/days • Synoptic scale – e.g. weather maps – Timescale: days to weeks • Planetary scale – Entire earth Scales of Motion Table 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion Turbulence • Eddies : internal friction generated as laminar (smooth, steady) flow becomes irregular and turbulent • Most weather disturbances involve turbulence • 3 kinds: – Mechanical turbulence – you, buildings, etc. – Thermal turbulence – due to warm air rising and cold air sinking caused by surface heating – Clear Air Turbulence (CAT) - due to wind shear, i.e. change in wind speed and/or direction Mechanical Turbulence • Mechanical turbulence – due to flow over or around objects (mountains, buildings, etc.) Mechanical Turbulence: Wave Clouds • Flow over a mountain, generating: – Wave clouds – Rotors, bad for planes and gliders! Fig. 7.2: Mechanical turbulence - Air flowing past a mountain range creates eddies hazardous to flying. Thermal Turbulence • Thermal turbulence - essentially rising thermals of air generated by surface heating • Thermal turbulence is maximum during max surface heating - mid afternoon Questions 1. A pilot enters the weather service office and wants to know what time of the day she can expect to encounter the least turbulent winds at 760 m above central Kansas. If you were the weather forecaster, what would you tell her? 2. -

Guam TWD Sample

AXPQ20 PGUM 020500 TROPICAL WEATHER DISCUSSION NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE TIYAN GU 3 PM CHST TUE MAR 2 2021 Tropical Weather Discussion for western North Pacific between the Equator and 25N from 130E to 180. The following information is based on recent satellite imagery/data, weather observations, radar, and meteorological analysis. …SIGNIFICANT FEATURES… Typhoon Fake (02W) continues to move westward across the Philippine Sea, west of the Marianas, at about 10 mph. It is currently centered near 13N136E with maximum sustained winds of 90 mph. Seas near the center range between 30 and 40 feet with large swell of 10 to 15 feet spread outward toward the Mariana Islands and far western Micronesia. Please see the latest NWS Guam Public Advisory for more details on Typhoon Fake at weather.gov/gum/Cyclones …OTHER WEATHER SYSTEMS… NEAR-EQUATORIAL TROUGH… The near-equatorial trough extends southeastward through 4N130E to near EQ150E, staying well south of Koror, Yap, and Chuuk. The trough, common for this time of year, has remained stationary the past several days with showers and thunderstorms periodically developing near the trough axis as far north as Koror. Moderate winds up to 15 mph are found near the trough. TRADE-WIND TROUGHS… Gentle to moderate trade winds are seen across the region from the Marianas eastward and across central and eastern Micronesia. Westward-moving trade-wind troughs are seen just east of the Marianas, north of Pohnpei, and moving through the western Marshall Islands with clusters of increased cloudiness and showers. TRADE-WIND SURGE… Latest Scatterometry data show moderate to fresh northeast trade winds between Yap and Chuuk. -

The Age of Exploration

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY Native American The Age of Exploration Teacher Guide Enslaved workers Spice trade John Cabot Crossing the ocean The Age of Exploration Teacher Guide Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Copyright © 2016 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge®, Core Knowledge Curriculum Series™, Core Knowledge History and Geography™ and CKHG™ are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. References herein should not be regarded as affecting the validity of said trademarks and trade names. -

MIS 11 Across the Northeast Atlantic

Clim. Past Discuss., 4, 433–457, 2008 www.clim-past-discuss.net/4/433/2008/ Climate of the Past CPD © Author(s) 2008. This work is distributed under Discussions 4, 433–457, 2008 the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Climate of the Past Discussions is the access reviewed discussion forum of Climate of the Past MIS 11 across the Northeast Atlantic J. P. Helmke et al. Uniform climate development between the Title Page subtropical and subpolar Northeast Abstract Introduction Atlantic across marine isotope stage 11 Conclusions References Tables Figures J. P. Helmke1, H. A. Bauch1,2, U. Rohl¨ 3, and E. S. Kandiano1 J I 1Leibniz Institute of Marine Sciences, Wischhofstr. 1–3, 24148 Kiel, Germany 2 Academy of Sciences, Humanities and Literature, Geschwister-Scholl-Str. 2, 55131 Mainz, J I Germany Back Close 3University of Bremen, Postfach 330440, 28334 Bremen, Germany Received: 12 March – Accepted: 18 March – Published: 9 April 2008 Full Screen / Esc Correspondence to: J. P. Helmke ([email protected]) Printer-friendly Version Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Interactive Discussion 433 Abstract CPD Proxy records from a core site off Northwest Africa were generated and compared with data from the subpolar Northeast Atlantic to unravel some main climatic features of in- 4, 433–457, 2008 terglacial marine isotope stage (MIS) 11 (423–362 ka). The records point to an almost 5 25 kyr lasting full interglacial period during stage 11 that was preceded by a consid- MIS 11 across the erably long glacial-interglacial transition (Termination V). Off NW Africa, a strong re- Northeast Atlantic duction of terrestrially derived iron input is noted after 420 ka suggesting a pronounced increase in continental humidity and vegetation cover over Northwest Africa. -

The Effects of the Trade Winds on the Distribution of Relative Humidity

y & W log ea to th a e im r l F C o f r e o Journal of Mendez-Tejeda et al., J Climatol Weather Forecasting 2015, 3:2 c l a a s n t r i n u g DOI: 10.4172/2332-2594.1000137 o J ISSN: 2332-2594 Climatology & Weather Forecasting Research Article Article OpenOpen Access Access The Effects of the Trade Winds on the Distribution of Relative Humidity and the Diurnal Air Temperature Cycle on Oceanic Tropical Islands Ronalds RT1, Emiliano A1 and Rafael Mendez-Tejeda2* 1School of Natural Science and Technology, Universidad del Turabo, Gurabo, PR, USA 2Atmospheric Sciences Laboratory, University of Puerto Rico at Carolina, PO Box 4800, Carolina, PR, USA Abstract On many oceanic tropical islands the trade winds blow from the east and as the air passes over the island it loses moisture to rain. The two hypotheses for this study are that the western part of the island is less humid and has a larger diurnal air temperature cycle. Using data available on the Internet, the two hypotheses were assayed 7 times on 6 different islands in the Pacific and Caribbean. The islands used in this study are Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, the Big Island of Hawaii, Maui, Oahu, and Kauai. The first hypothesis was tested only on Hispaniola and is true. The second hypothesis was tested on all the islands and is true on all the islands except on the Big Island of Hawaii and Maui. Using a p-value of 0.05, these hypotheses are as predicted 5 of the 7 times, which has a p-value of 6 x 10-6.