What's Next After the Red-Footed Falcon? Predictions of Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapid Formation and Degradation of Barrier Spits in Areas with Low Rates of Littoral Drift*

Marine Geology, 49 (1982) 257-278 257 Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam- Printed in The Netherlands RAPID FORMATION AND DEGRADATION OF BARRIER SPITS IN AREAS WITH LOW RATES OF LITTORAL DRIFT* D.G. AUBREY and A.G. GAINES, Jr. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543 (U.S.A.) (Received February 8, 1982; revised and accepted April 6, 1982) ABSTRACT Aubrey, D.G. and Gaines Jr., A.G., 1982. Rapid formation and degradation of barrier spits in areas with low rates of littoral drift. Mar. Geol., 49: 257-278. A small barrier beach exposed to low-energy waves and a small tidal range (0.7 m) along Nantucket Sound, Mass., has experienced a remarkable growth phase followed by rapid attrition during the past century. In a region of low longshore-transport rates, the barrier spit elongated approximately 1.5 km from 1844 to 1954, developing beyond the baymouth, parallel to the adjacent Nantucket Sound coast. Degradation of the barrier spit was initiated by a succession of hurricanes in 1954 (Carol, Edna and Hazel). A breach opened and stabilized near the bay end of the one kilometer long inlet channel, providing direct access for exchange of baywater with Nantucket Sound, and separating the barrier beach into two nearly equal limbs. The disconnected northeast limb migrated shorewards, beginning near the 1954 inlet and progressing northeastward, filling the relict inlet channel behind it. At present, about ten percent of the northeast limb is subaerial: the rest of the limb has completely filled the former channel and disappeared. The southwest limb of the barrier beach has migrated shoreward, but otherwise has not changed significantly since the breach. -

Summary of 2017 Massachusetts Piping Plover Census Data

SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS Bill Byrne, MassWildlife SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS ABSTRACT This report summarizes data on abundance, distribution, and reproductive success of Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus) in Massachusetts during the 2017 breeding season. Observers reported breeding pairs of Piping Plovers present at 147 sites; 180 additional sites were surveyed at least once, but no breeding pairs were detected at them. The population increased 1.4% relative to 2016. The Index Count (statewide census conducted 1-9 June) was 633 pairs, and the Adjusted Total Count (estimated total number of breeding pairs statewide for the entire 2017 breeding season) was 650.5 pairs. A total of 688 chicks were reported fledged in 2017, for an overall productivity of 1.07 fledglings per pair, based on data from 98.4% of pairs. Prepared by: Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 2 SUMMARY OF THE 2017 MASSACHUSETTS PIPING PLOVER CENSUS INTRODUCTION Piping Plovers are small, sand-colored shorebirds that nest on sandy beaches and dunes along the Atlantic Coast from North Carolina to Newfoundland. The U.S. Atlantic Coast population of Piping Plovers has been federally listed as Threatened, pursuant to the U.S. Endangered Species Act, since 1986. The species is also listed as Threatened by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife pursuant to Massachusetts’ Endangered Species Act. Population monitoring is an integral part of recovery efforts for Atlantic Coast Piping Plovers (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1996, Hecht and Melvin 2009a, b). It allows wildlife managers to identify limiting factors, assess effects of management actions and regulatory protection, and track progress toward recovery. -

Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan

Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan Volume 2 Baseline Assessment and Science Framework December 2009 Introduction Volume 2 of the Massachusetts Ocean Management Plan focuses on the data and scientific aspects of the plan and its implementation. It includes these two separate documents: • Baseline Assessment of the Massachusetts Ocean Planning Area - This Oceans Act-mandated product includes information cataloging the current state of knowledge regarding human uses, natural resources, and other ecosystem factors in Massachusetts ocean waters. • Science Framework - This document provides a blueprint for ocean management- related science and research needs in Massachusetts, including priorities for the next five years. i Baseline Assessment of the Massachusetts Ocean Management Planning Area Acknowledgements The authors thank Emily Chambliss and Dan Sampson for their help in preparing Geographic Information System (GIS) data for presentation in the figures. We also thank Anne Donovan and Arden Miller, who helped with the editing and layout of this document. Special thanks go to Walter Barnhardt, Ed Bell, Michael Bothner, Erin Burke, Tay Evans, Deb Hadden, Dave Janik, Matt Liebman, Victor Mastone, Adrienne Pappal, Mark Rousseau, Tom Shields, Jan Smith, Page Valentine, John Weber, and Brad Wellock, who helped us write specific sections of this assessment. We are grateful to Wendy Leo, Peter Ralston, and Andrea Rex of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority for data and assistance writing the water quality subchapter. Robert Buchsbaum, Becky Harris, Simon Perkins, and Wayne Petersen from Massachusetts Audubon provided expert advice on the avifauna subchapter. Kevin Brander, David Burns, and Kathleen Keohane from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection and Robin Pearlman from the U.S. -

Range Expansion and New Breeding Record for the Glossy Ibis in Massachusetts

RANGE EXPANSION AND NEW BREEDING RECORD FOR THE GLOSSY IBIS IN MASSACHUSETTS by Robert C. Humphrey The purpose of this paper is twofold: first, to give a brief summary of the history of the Glossy Ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) in North America and its northward expansion into Massachusetts; and second, to report on a new breeding location in the state. The Glossy Ibis is believed to be a fairly recent arrival in America from the Old World. Although very little literature exists as to how and when it arrived in the new world, Audubon (1967) noted the "first intimation" of this species in the United States as a bird shot in Maryland in 1817. By 1837 he referred to them as existing in vast numbers in Mexico and in flocks, but only as a summer resident, in Texas. Specimens appeared in the Boston Market around 1844. The first documentation of a live bird in Massachusetts was around 1850 (Audubon 1967, Bent 1926). By 1870 ibises were rare and local in the southeastern United States from Louisiana to Florida. Casual records existed north to Missouri, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ontario, and Nova Scotia (Pearson 1956). The first authentic breeding records occurred in Florida in the 1880s (Palmer 1962). The breeding range in this country was restricted to Texas and Florida for most of the first half of the 1900s. Ibises slowly expanded their breeding range into North and South Carolina in 1944 and 1947, respectively. A more rapid expansion took place in the 1950s. They first bred in New Jersey in 1955 and in Maryland in 1956 (Stewart 1957). -

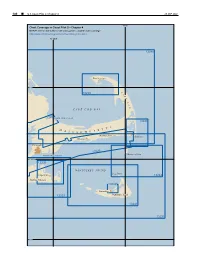

Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound

186 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 26 SEP 2021 70°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 4 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 70°30'W 13246 Provincetown 42°N C 13249 A P E C O D CAPE COD BAY 13229 CAPE COD CANAL 13248 T S M E T A S S A C H U S Harwich Port Chatham Hyannis Falmouth 13229 Monomoy Point VINEYARD SOUND 41°30'N 13238 NANTUCKET SOUND Great Point Edgartown 13244 Martha’s Vineyard 13242 Nantucket 13233 Nantucket Island 13241 13237 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 ¢ 187 Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound (1) This chapter describes the outer shore of Cape Cod rapidly, the strength of flood or ebb occurring about 2 and Nantucket Sound including Nantucket Island and the hours later off Nauset Beach Light than off Chatham southern and eastern shores of Martha’s Vineyard. Also Light. described are Nantucket Harbor, Edgartown Harbor and (11) the other numerous fishing and yachting centers along the North Atlantic right whales southern shore of Cape Cod bordering Nantucket Sound. (12) Federally designated critical habitat for the (2) endangered North Atlantic right whale lies within Cape COLREGS Demarcation Lines Cod Bay (See 50 CFR 226.101 and 226.203, chapter 2, (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are for habitat boundary). It is illegal to approach closer than described in 33 CFR 80.135 and 80.145, chapter 2. -

Bird Observer VOLUME 34, NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY 2006 HOT BIRDS

Bird Observer VOLUME 34, NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY 2006 HOT BIRDS Phil Brown captured this image of a Selasphorous hummingbird (left) visiting Richard and Kathy Penna’s Boxford feeder. The bird remained for several weeks, and Phil Brown took this photo on November 20, 2005. On November 21, 2005, Linda Pivacek discovered a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher (right) at the Swampscott Beach Club, and Robb Kipp captured this breathtaking photo. This cooperative bird delighted many visitors over the following weeks. At Wellfleet Harbor, Blair Nikula picked out a Franklin’s Gull (left) in a large feeding flock on November 26, 2005. On December 11, Erik Nielsen took this stunning portrait of the cooperative rarity. On December 2, 2005, Gwilym Jones discovered a female Varied Thrush (right) on the Fenway in Boston. Andrew Joslin took this great photograph of this western wanderer. This bird was reported by many observers through January, 2006. CONTENTS BIRDING IN EAST BOSTON, WINTHROP, REVERE, AND SAUGUS Soheil Zendeh 5 MASSACHUSETTS IMPORTANT BIRD AREAS (IBAS) — THE SOUTH SHORE REGION Wayne R. Petersen and Brooke Stevens 26 LETTER TO THE EDITORS 32 ASUMMER AT MONOMOY Ryan Merrill 34 FIELD NOTE Latest Occurence of Arctic Tern for Massachusetts Richard R. Veit and Carolyn S. Mostello 38 ABOUT BOOKS Virtual Encyclopedia Ornithologica: The Birds of North America On-line Mark Lynch 40 BIRD SIGHTINGS September/October 2005 45 ABOUT THE COVER: Wild Turkey William E. Davis, Jr. 63 ABOUT THE COVER ARTIST: Barry Van Dusen 64 ATA GLANCE Wayne R. Petersen 465 IMMATURE NORTHERN SHRIKE BY DAVID LARSON BIRD OBSERVER Vol. 34, No. -

CHATHAM WATERS and SHORELINES

CHATHAM WATERS and SHORELINES THEN and NOW 1712- 2012 FRIENDS OF CHATHAM WATERWAYS 1 FOREWORD riends of Chatham Waterways joins in celebration of Chatham’s Tercentennial by publishing this collection of Fsketches, maps, charts and photographs depicting a story about Chatham waters and shorelines from Chatham’s beginning to the present. This pictorial account of the Town’s waters and shorelines, going back over 400 years, reinforces our present-day experience of shifting sands, shoaling, of new and closed inlets. Readers will see patterns and repetitions that may guide us in suitable actions. This booklet is being distributed to all Chatham households because it is not only the shore side residents who have interest in and impact on our waterways; it is all of us who live in Chatham. Founded in 1983, Friends of Chatham Waterways is a non-profit organization of individuals committed to the protection, wise use and enjoyment of Chatham’s fresh and salt waterways and adjoining lands. With 66 miles of shoreline, we believe our bays, harbors, estuaries, ponds, lakes and rivers are fundamental to the town’s heritage, providing commercial and recreational opportunities while adding to its environmental and economic health. If you are not already a member of Friends of Chatham Waterways, please join us in our commitment to improve our community environment. A membership form is included for all who are concerned about our harbors, estuaries, lakes, ponds and rivers. Additional copies of CHATHAM WATERS and SHORELINES are available by request to the logo address above. Our website (www.chathamwaterways.org) contains the electronic version. -

Marthas-Vineyard-Vacation-Planner

With so many great reasons to visit the Island of of Nantucket Martha's Vineyard, it is difficult to single out just required to head out three. Two of the best-known features of the Island to sea or when they are its beautiful beaches and nature reserves and returned with their the magnificent, historic, whaling captains' homes catch. with their rose-strewn white picket fences. But the following are three equally compelling sights to see After the demise of and experience there: the whaling industry early in the 1870s, Menemsha Sword Fisherman Sculpture The Vineyard's working farms the Vineyard continued to make a living fishing and farming, but Martha’s Vineyard may be known as the summer these enterprises didn’t bring in much money from playground for the rich and famous, including the mainland. Because the Cape Cod Canal was presidents and their – some of whom own or enjoy not then in existence, many Vineyarders assisted beautiful Martha's Vineyard vacation rentals. But it the sailing ships transporting goods from Boston to New York through the treacherous waters around the Cape and Islands. This, however, wasn’t financially rewarding, so Islanders continued providing for themselves on their land and in the Island waters. After World War II, tourism began to take off on the Vineyard as soldiers who had been stationed there returned home to tell of the Island’s beauty. Fortunately, many Islanders still put great importance on being self-sufficient and providing “Island grown” produce and goods. Today, 28 working farms and countless backyard gardens continue the tradition of those who founded the Alpaca Farm, Martha’s Vineyard Island. -

EFSB 02-2 for Approval to Construct Two 115 Kv ) Electric Transmission Lines ) ______)

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS Energy Facilities Siting Board ____________________________________ In the Matter of the Petition of Cape Wind ) Associates, LLC and Commonwealth ) Electric Company, d/b/a NSTAR Electric ) EFSB 02-2 for Approval to Construct Two 115 kV ) Electric Transmission Lines ) ____________________________________) FINAL DECISION M. Kathryn Sedor Presiding Officer May 11, 2005 On the Decision: William Febiger Barbara Shapiro John Young APPEARANCES: David S. Rosenzweig, Esq. Keegan, Werlin & Pabian, LLP 265 Franklin Street, 6th Floor Boston, Massachusetts 02110-3113 FOR: Cape Wind Associates, LLC Petitioner Mary E. Grover, Esq. Assistant General Counsel NSTAR Electric & Gas Corporation 800 Boylston Street, P1700 Boston, Massachusetts 02199 FOR: Commonwealth Electric Company d/b/a NSTAR Electric Petitioner Kenneth L. Kimmell, Esq. Jeffrey M. Bernstein, Esq. Elisabeth C. Goodman, Esq. Bernstein, Cushner & Kimmell, P.C. 585 Boylston Street, Suite 400 Boston, Massachusetts 02116 FOR: Town of Yarmouth Intervenor Myron Gildesgame, Director Office of Water Resources Department of Environmental Management 251 Causeway Street, Suite 600 Boston, Massachusetts 02114 FOR: Department of Environmental Management Ocean Sanctuaries Act Program Intervenor Christopher H. Kallaher, Esq. Robinson & Cole LLP One Boston Place Boston, Massachusetts 02108 FOR: Alliance to Protect Nantucket Sound Intervenor -i- Douglas H. Wilkins, Esq. Anderson & Kreiger LLP 43 Thorndike Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02141 FOR: Massachusetts Audubon Society Intervenor David P. Dwork, Esq. Roger T. Manwaring, Esq. Barron & Stadfeld, P.C. 100 Cambridge Street, Suite 1310 Boston, Massachusetts 02114 FOR: Save Popponesset Bay, Inc. Intervenor Paige Graening, Esq. National Grid USA Service Company 25 Research Drive Westborough, Massachusetts 01582 FOR: Nantucket Electric Company Limited Participant Margo Fenn, Executive Director Cape Cod Commission 3225 Main Street P.O. -

Historical Shoreline Change Along the New England and Mid-Atlantic Coasts

IV Report Title National Assessment of Shoreline Change: Historical Shoreline Change along the New England and Mid-Atlantic Coasts Open-File Report 2010–1118 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey COVER: The cover is an oblique aerial photograph of Brigantine Inlet, looking south toward Atlantic City, NJ. National Assessment of Shoreline Change: Historical Shoreline Change along the New England and Mid-Atlantic Coasts by Cheryl J. Hapke, Emily A. Himmelstoss, Meredith G. Kratzmann, Jeffrey H. List, and E. Robert Thieler Open-File Report 2010-1118 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 This report and any updates to it are available online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2010/1118/ For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS (1-888-275-8747) For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Suggested citation: Hapke, C.J., Himmelstoss, E.A., Kratzmann, M., List, J.H., and Thieler, E.R., 2010, National assessment of shoreline change: Historical shoreline change along the New England and Mid-Atlantic coasts: U.S. -

Ecosystems and Resources of the Massachusetts Coast

ECOSYSTEMS AND RESOURCES, OF THE MASSACHUSETTS COAST .....-_-- .. •. / '- .. ~, \ '.' . - ..... INSTITUTE FOR MAN -,-...,,~,.. :-- .AND ENVIRONMENT - ...........:r"l -;.- / -,-.--"-,, T"'- - 2 24 TABLE OF CONENTS Acknowledgements Introduction 3 We wish to thank the following persons and organizations who generously provided their I The Geology of the Massachusetts Coast 5 time and facilities to help us prepare this document. First to our scientific advisory The Glacial Influence 5 panel, Professors Charles Cole, Dayton Carritt, The Dynamic Coastline 6 Craig Edwards, Paul Godfrey and James Nature's Stabilizers 10 Parrish, of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, we offer appreciation for their critical II The living Systems of the Coast 11 and patient review of our manuscript. We also The Ecosystem 11 extend our gratitude to the staff of the Massachusetts Coastal Zone Management Ecosystem Management 12 Program, Executive Office of Environmental Salt Marsh 13 Affairs, for their assistance. Others who Eelgrass Beds 16 provided help are: John Dennis, Nantucket; Sand Dunes 17 Ralph Goodno and Thomas Quink, Cooperative Sand Beaches 20 Extension Service; Dr. James Baird, Tidal Flats 23 Massachusetts Audubon; Allen Look, Nor thampton; Clifford Kaye, U.S. Geological Rocky Shores 24 Survey; Dr. Phillip Stanton, Framingham State Composite Ecosystems 26 College; and Dr. Joseph Hartshorn, University Salt Ponds 26 of Massachusetts. Barrier Beaches-Islands 28 Thanks are due also to the Metropolitan Estuaries 29 District Commission and Massachusetts Inventory Maps of Mass. Coast 34 Division of Forests and Parks for providing us boat trips in Boston Harbor; and Carlozzi, Sinton and Vilkitis, Inc. for the use of their four III Coastal Resources and Their Cultural Uses 44 wheel drive vehicle. -

Table 1), from a Total of 229 Sites Surveyed (Tables 1, 2)

SUMMARY OF 2009 CENSUS OF AMERICAN OYSTERCATCHERS IN MASSACHUSETTS Compiled by: Scott M. Melvin Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Westborough, MA 01581 July 30, 2010 SUMMARY OF 2009 CENSUS OF AMERICAN OYSTERCATCHERS IN MASSACHUSETTS INTRODUCTION This report summarizes data collected during a statewide census of the American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) in Massachusetts during the 2009 breeding season. This census was conducted by observers affiliated with a statewide network of cooperating agencies and organizations. The American Oystercatcher is a large, strikingly colored shorebird that nests on coastal beaches along the Atlantic Coast from Maine to Florida. Although the species has expanded its range and increased in abundance in New England over the past 50 years, its range extension northward along the Atlantic Coast may well be a recolonization of formerly occupied habitat (Forbush 1912). On a continental scale, the American Oystercatcher is one of the most uncommon species of breeding shorebirds in North America and is designated a Species of High Concern in the United States Shorebird Conservation Plan (Brown et. al. 2001). METHODS Data on American Oystercatcher abundance, distribution, and reproductive success were collected by a coast-wide group of cooperators that included full-time and seasonal biologists and coastal waterbird monitors, beach managers, researchers, and volunteers. This is the same group that conducts annual censuses of Piping Plovers and terns in Massachusetts (Melvin 2010, Mostello 2010). Observers censused adult oystercatchers during or as close as possible to the designated census period of 22 - 31 May 2009, in order to minimize double-counting of birds that might move between multiple sites during the breeding season.