Sacred Music Volume 119 Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTICLES Liturgical Music: the Medium and the Message | Fr

SACRED MUSIC Volume 142, Number 4 Winter 2015 EDITORIAL Sing the Mass | William Mahrt 3 ARTICLES Liturgical Music: The Medium and the Message | Fr. Richard Cipolla 7 Mystery in Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony | Daniel J. Heisey O.S.B. 18 A Brief History of the Ward Method and the Importance of Revitalizing Gregorian Chant and The Ward Method in Parochial School Music Classrooms | Sharyn L. Battersby 25 DOCUMENT Words of Thanks of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI on the Occasion of the Conferral of a Doctorate honoris causa by John Paul II Pontifi cal University of Krakow and the Krakow Academy of Music | Pope Benedict XVI 47 REPERTORY In paradisum, the Conclusion of the Funeral Mass | William Mahrt 50 REVIEW Johann Sebastian Bach: Sämtliche Orgelwerke, Volumes 1 & 2: Preludes and Fugues |Paul Weber 53 COMMENTARY Black | William Mahrt 57 NEWS CMAA Annoucements 59 SACRED MUSIC Formed as a continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America since its inception in 1965. Offi ce of Publication: 12421 New Point Drive, Richmond, VA 23233. E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.musicasacra.com Editor: William Mahrt Managing Editor: Jennifer Donelson Editor-at-Large: Kurt Poterack Typesetting: Judy Thommesen Membership & Circulation: CMAA, P.O. Box 4344, Roswell, NM 88202 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Offi cers and Board of Directors President: William Mahrt Vice-President: Horst Buchholz Secretary: Mary Jane Ballou Treasurer: Adam Wright Chaplain: Rev. -

Pdf • an American Requiem

An American Requiem Our nation’s first cathedral in Baltimore An American Expression of our Roman Rite A Funeral Guide for helping Catholic pastors, choirmasters and families in America honor our beloved dead An American Requiem: AN American expression of our Roman Rite Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, And let perpetual light shine upon them. And may the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, Rest in Peace. Amen. Grave of Father Thomas Merton at Gethsemane, Kentucky "This is what I think about the Latin and the chant: they are masterpieces, which offer us an irreplaceable monastic and Christian experience. They have a force, an energy, a depth without equal … As you know, I have many friends in the world who are artists, poets, authors, editors, etc. Now they are well able to appre- ciate our chant and even our Latin. But they are all, without exception, scandalized and grieved when I tell them that probably this Office, this Mass will no longer be here in ten years. And that is the worst. The monks cannot understand this treasure they possess, and they throw it out to look for something else, when seculars, who for the most part are not even Christians, are able to love this incomparable art." — Thomas Merton wrote this in a letter to Dom Ignace Gillet, who was the Abbot General of the Cistercians of the Strict Observance (1964) An American Requiem: AN American expression of our Roman Rite Requiescat in Pace Praying for the Dead The Carrols were among the early founders of Maryland, but as Catholic subjects to the Eng- lish Crown they were unable to participate in the political life of the colony. -

Jean Langlais Remembered: Chapter-9

The Upheavals of the Sixties ! ! ! CHAPTER 9 The$Upheavals$of$the$Sixties$ Jean Langlais’s mature years should have unfolded smoothly as his fame increased, but it was not to be. A major upheaval would rock the Roman Catholic Church, a budding ecumenical movement would gain momentum, and the world of French organists would split along fault lines between proponents of Baroque, Romantic, and contemporary music. Jean Langlais suddenly found himself doing battle on multiple fronts, under attack from the liturgical consequences of Vatican II on the one hand, and confronting new ideas from younger colleagues on the other. In spite of the resulting tumult, he would continue to advance his career as a brilliant recitalist and teacher, attracting a growing number of foreign organ students along the way. The Second Vatican Council: Jean Langlais confronts the evolution of the Roman Catholic liturgy We arrive at what proved to be one of the saddest moments in the life of Jean Langlais. For some time he had been considered a specialist of the highest order in the domain of Roman Catholic sacred music, most notably since 1954-1955 and the success of his Missa Salve Regina. The Second Vatican Council, particularly as interpreted by certain French liturgists, now stood poised to completely disrupt the happy order of his life as a composer. His six choral masses in Latin, a Passion, and numerous motets and cantatas notwithstanding, Langlais initially reacted with enthusiasm to the Church’s new directives concerning religious music, composing many simple works in French that were directly accessible to the faithful. -

Living an Indulgenced Life St

Living an Indulgenced Life St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church Living an Indulgenced Life PRAYER OF ST. FRANCIS SERRAN PRAYER FOR VOCATIONS Lord, make me an instrument of your peace. / O God, Who wills not the death of a sinner, / but Where there is hatred, let me sow love. / Where rather that he be converted and live. / Grant we there is injury, pardon. / Where there is doubt, beseech You / through the intercession of the faith. / Where there is despair, hope. / Where Blessed Mary ever Virgin, / Saint Joseph her there is darkness, light. / Where there is spouse, / Saint Junipero Serra / and all the sadness, joy. / O Divine Master, grant that I may saints, / an increase of laborers for Your not so much seek to be consoled as to console, Church, / fellow laborers to spend and consume / to be understood as to understand, / to be themselves for souls, / through the same Jesus loved as to love, / for it is in giving that we Christ, Your Son, / Who lives and reigns with receive, / it is in pardoning that we are You in the unity of the Holy Spirit, / one God pardoned, / and it is in dying that we are born to forever and ever. eternal life. PRAYER FOR A STEWARDSHIP PARISH PRAYER FOR PRIESTS My parish is composed of people like me. / I Dear Lord, we pray that the Blessed Mother / help make it what it is. / It will be friendly if I am. wrap her mantle around Your priests / and / It will be holy if I am. / Its pews will be filled if I through her intercession / strengthen them for help fill them. -

Mcneil Robinson As Choral Musician a Survey of His Choral Works for the Christian and Jewish Traditions Jason Allen Wright University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 Mcneil Robinson as Choral Musician A Survey of his Choral Works for the Christian and Jewish Traditions Jason Allen Wright University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Wright, J. A.(2017). Mcneil Robinson as Choral Musician A Survey of his Choral Works for the Christian and Jewish Traditions. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4210 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MCNEIL ROBINSON AS CHORAL MUSICIAN A SURVEY OF HIS CHORAL WORKS FOR THE CHRISTIAN AND JEWISH TRADITIONS by Jason Allen Wright Bachelor of Music East Carolina University, 2003 Master of Music University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2004 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Conducting School of Music University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Larry Wyatt, Major Professor Alicia Walker, Committee Member Andrew Gowan, Committee Member Julie Hubbert, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Jason Allen Wright, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This document is dedicated to God, who knew me before I was born and gave me the gift of music. To my parents, Tommy A. and Ruby N. Wright, who gave me life and who continue to love and support me throughout my life and musical journey. -

The Parish Book of Chant, 2Nd Edition

The Parish Book of Chant Expanded Second Edition The Parish Book of Chant Expanded Second Edition A Manual of Gregorian Chant and a Liturgical Resource for Scholas and Congregations including Order of Sung Mass for oth Ordinary and Extraordinary Forms of the Roman Rite with a complete Kyriale, along with Chants and Hymns for Occasional and Seasonal Use and their literal English translations Prepared for the The Church Music Association of America Copyright ( 2012 CMAA Creati,e Commons Attri ution 3.0 http/00creati,ecommons.org0licenses0by03.00 Excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal ( 2010 International Commission on English in the Liturgy Corporation. All rights reser,ed. Dedicated to His Holiness, Pope Benedict XVI, in thanksgiving for his otu proprio, Su oru Pontificu and to Msgr. Andrew Wadsworth, Executive Director, ICEL Secretariat, Washington, D.C. TABLE OF CO2TE2TS page no. OR3ER OF SU2G MASS, OR312AR4 FORM Introductory Rite................................................................... 2 Penitential Act ...................................................................... 3 1. Confiteor................................................................................ 3 2. Miserere nostri....................................................................... 5 3. Petitions with 6yrie............................................................... 7 5. 6yrie, Missa XVI.................................................................... 7 7. Gloria, Missa VIII ................................................................. -

Requiem: an Original Composition for Choir

REQUIEM: AN ORIGINAL COMPOSITION FOR CHOIR, SOLOISTS, AND CHAMBER WIND ENSEMBLE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY STEPHANIE R. KISSELBAUGH DISSERTATION ADVISORS: DRS. ANDREW CROW AND ELEANOR TRAWICK BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2018 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii Chapter 1. Introduction 1 Chapter 2. A Brief History of the Requiem Mass 5 Chapter 3. Text Setting Conventions 15 Chapter 4. Formal Structure 38 Chapter 5. Genesis of the Kisselbaugh Requiem 71 Chapter 6. Analysis of the Kisselbaugh Requiem 83 Chapter 7. Performance Considerations and Conclusion 101 BIBLIOGRAPHY 107 APPENDIX 1: MUSICAL SCORE OF Requiem 109 Introit 111 Kyrie 129 Tract 143 Sequence Dies irae 149 Quid sum miser 162 Pie Jesu 188 Sanctus 195 In Paradisum 213 Agnus Dei 223 Libera me 237 APPENDIX 2: Movements Included in Selected Requiems 255 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of a lifetime of music. Music has always been an important aspect in my life and all of my earliest memories include music in some way. Music has always been there as a source of joy and comfort. I am truly lucky that I was encouraged along this path that I chose to take. First, I want to thank my committee co-chairs, Drs. Andrew Crow and Eleanor Trawick. Both have taught me so much and encouraged me to keep working, even when I wanted to stop. They have put a tremendous amount of work into assisting me with this project and I could not have finished without their guidance. -

An Introduction to the Choral Music of Galina Grigorjeva. Docx

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE CHORAL MUSIC OF GALINA GRIGORJEVA BY WON JOO AHN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Music with a concentration in Choral Music in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Andrew Megill, Chair and Director of Research Professor Barrington L. Coleman Teaching Associate Professor Andrea Solya Associate Professor Bridget Sweet ABSTRACT This study will examine Galina Grigorjeva’s compositional style and the influence of the Russian Orthodox tradition on her choral music. Grigorjeva, born in 1962, is a Ukraine-born Estonian composer, and has written over seventy compositions to date, twenty-two of which are choral works. She currently works as a freelancer composer in Tallinn, Estonia. This study begins with Grigorjeva’s professional biography and an overview of her background and education. It includes a discussion of Byzantine and Znamenny chants and how these traditions contribute to a deeper understanding of Grigorjeva’s music. It will then discuss some of the musical influences and the characteristics of Grigorjeva’s music, including her approach to rhythm, text, harmony, texture, timbre, and melody. Three selected choral works—On Leaving (1999), Nature Morte (2008), and In paradisum (2012)—which collectively exemplify the composer’s unique compositional style will then be investigated. Additionally, this study will offer an annotated catalog of Grigorjeva’s entire choral output to benefit readers in adding fresh choral repertoire. The purpose of this exploration is to introduce this great composer and her works to choral musicians looking for hidden gems of choral literature. -

Sacred Music Volume 119 Number 4

SACRED MUSIC (Winter) 1992 Volume 119, Number 4 Church of Orosi, Costa Rica SACRED MUSIC Volume 119, Number 4, Winter 1992 FROM THE EDITORS The Attack on the Church Musician 3 In Paradisum 5 CONCILIAR CONSTITUTION: SACROSANCTUM CONCILIUM Monsignor Richard J. Schuler 7 THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME IN LITURGY Reverend Deryck Hanshell, S. J. 15 A LETTER TO A FRIEND Karoly Kope 19 REVIEWS 21 NEWS 24 OPEN FORUM 25 CONTRIBUTORS 26 INDEX TO VOLUME 119 27 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publications: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103. Editorial Board: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, Editor Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Rev. John Buchanan Harold Hughesdon William P. Mahrt Virginia A. Schubert Cal Stepan Rev. Richard M. Hogan Mary Ellen Strapp News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Paul Salamunovich, 10828 Valley Spring Lane, N. Hollywood, Calif. 91602 Paul Manz, 1700 E. 56th St., Chicago, Illinois 60637 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Monsignor Richard J. Schuler Vice-President Gerhard Track General Secretary Virginia A. Schubert Treasurer Earl D. Hogan Directors Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Mrs. Donald G. Vellek William P. Mahrt Rev. Robert A. Skeris Members in the Church Music Association of America includes a subscrip- tion to SACRED MUSIC. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reprWuction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 36mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photogr aphie print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. Order Number 8717593 Requiem Mass for chorus and orchestra; with a monograph on the history, regulation, and content of the Missa pro defunctis. [Original composition] Onofrio, Marshall Paul, D.M.A. The Ohio State University, 1987 Copyright ©1987 by Onofrio, Marshall Paul. All rights reserved. UMI SOON.ZeebRd. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

In the Michaelmas 2002 Issue – 116

In the Michaelmas 2002 issue – 116 Recte Nunc Celebramus – Editorial ……………………..…..….. AGM at Leicester in October – full details ………………….…… Towards Advent – Westminster in November ………………….. Mass Changes in Central London ……………………………….. Advance Notice – Spring 2003 in Derby ..…………..….….…….. Spring Meeting in Elgar Country – Report ………………………. Requiem for Martin Lynch and Ruth Richens ………….……….. Ruth Richens – Obituary by Bernard Marriott …………….…….. Roman Missal 2000 – Appreciation by Fr Guy Nicholls ………… Fr Bruce Harbert – to be Executive Secretary of ICEL ……..…… Observations – Translation of the Roman Missal ………………… D Crouan: Liturgy after Vatican II – by Anthony McClaran …..… K Gamber: The Modern Rite – by Henry Taylor ………………… Holy Week in Rome – by Lewis Berry …………………………… Farewell Xavier Rynne – Mole at the Council…………………… Et Postremo – Tailpiece …………………………………………... RECTE NUNC CELEBRAMUS Editorial If today we do not feel happier and more confident than for many years, it can only be that we have so far failed to recognize the full import of the promulgation of the third edition of the Missale Romanum. Here we have the definitive blueprint for Catholic worship for generations to come. In producing this handsome volume, in Latin, clearly intended to be used in the sanctuary, with abundant use of Gregorian chant, Rome has signalled its desire for our liturgy, the transcendent living Latin liturgy, to be resurgent indeed. This surely calls for unstinting celebration in both senses of the word. Fr Guy Nicholls has contributed a valuable appreciation of the new edition of the Missal which we are delighted to publish in this Newsletter. 1 Although the Missal is now much better presented and more complete, all the essential texts are unchanged and our existing Latin liturgical books remain usable, especially those so beautifully produced by the monks of Solesmes, such as the Ordo Missæ in Cantu and the Graduale Romanum. -

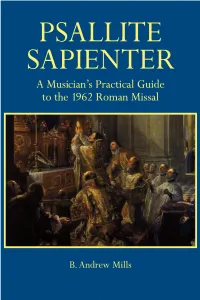

PSALLITE SAPIENTER Psallite Sapienter Sing Ye Praises with Understanding (Psalm 46.7) PSALLITE SAPIENTER

PSALLITE SAPIENTER Psallite sapienter Sing ye praises with understanding (Psalm 46.7) PSALLITE SAPIENTER A MUSICIAN’S PRACTICAL GUIDE TO THE 1962 ROMAN MISSAL B. Andrew Mills Church MusicCMAA Association of America Cover design by Donald Cherry Juan Carreño de Miranda (1614–1685): Saint John of Matha celebrating Mass (detail), 1666; Musée du Louvre, Paris Special thanks to Fr. Joseph Howard, F.S.S.P., for advice in matters liturgical. Copyright © 2008 Church Music Association of America Church Music Association of America 12421 New Point Drive, Harbour Cove, Richmond, Virginia 23233 Fax 240-363-6480 [email protected] website musicasacra.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 7 BASIC CONCEPTS AND TERMS . .9 Three Types of Mass . .9 Necessary and Unnecessary Music . .9 Cantor(s), Schola, and Choir; Congregational Singing; Organist and Choirmaster . .12 Alternation . .13 The Use (and non-use) of the Organ . .14 THE MUSIC OF MISSA SOLEMNIS OR MISSA CANTATA . .17 Sprinkling of Holy Water . .17 Introit . .18 Kyrie . .20 Gloria . .20 Collect . .22 Epistle and Gradual . .22 Alleluia and Sequence . .22 Gospel and Sermon . .23 Credo . .24 Offertory . .25 Preface; Sanctus and Benedictus . .25 End of the Canon and Pater Noster; Agnus Dei . .27 Communion . .28 Post-Communion and Ite, missa est . .29 5 6 Psallite Sapienter: A Musician’s Practical Guide to the 1962 Roman Missal SPECIAL DAYS AND SEASONS . .31 Advent . .31 Christmas and its Vigil . .31 Sundays after Epiphany . .32 Candlemas . .32 Septuagesima . .33 Ash Wednesday and Lent . .34 Passion Sunday and Passiontide . .35 Palm Sunday . .35 Maundy Thursday . .37 Good Friday . .38 Easter Vigil .