Geography of Canada GEO421A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 of 10 Course Syllabus Geography of Canada

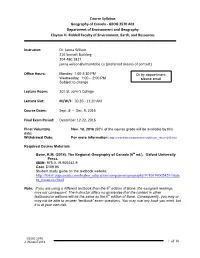

Course Syllabus Geography of Canada - GEOG 2570 A01 Department of Environment and Geography Clayton H. Riddell Faculty of Environment, Earth, and Resources Instructor: Dr. Janna Wilson 216 Sinnott Building 204.480.1817 [email protected] (preferred means of contact) Office Hours: Monday: 1:00-2:30 PM Or by appointment; Wednesday: 1:00 – 2:00 PM please email Subject to change Lecture Room: 201 St. John’s College Lecture Slot: M/W/F: 10:30 - 11:20 AM Course Dates: Sept. 8 – Dec. 9, 2016 Final Exam Period: December 12-22, 2016 Final Voluntary Nov. 18, 2016 (50% of the course grade will be available by this date) Withdrawal Date: For more information: http://umanitoba.ca/student/records/leave_return/695.html Required Course Materials Bone, R.M. (2014). The Regional Geography of Canada (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN: 978-0-19-900242-9 Cost: $109.95 Student study guide on the textbook website: http://www.oupcanada.com/higher_education/companion/geography/9780199002429/stude nt_resources.html Note: If you are using a different textbook than the 6th edition of Bone, the assigned readings may not correspond. The instructor offers no guarentee that the content in other textbooks/or editions will be the same as the 6th edition of Bone. Consequently, you may or may not be able to answer “textbook” exam questions. You may use any book you want, but it is at your own risk. GEOG 2570 J. Wilson/F2016 1 of 10 Course Description: (Formerly 053.257) A regional study of Canada in which the major regions of Canada are studied with respect to geographical patterns of their physical environment, settlement, culture, economic activity, and land use. -

Canada and the American Curriculum

Canada and the American Curriculum REQUIRED Where is Canadian content taught, at what level, in what course? Recommended: HISTORY Data current as of January 2013 Recommended: ECONOMICS Recommended: GEOGRAPHY Recommended: CIVICS State Elem K-5 Specifics Middle 6-8 Specifics High 9-12 Specifics Grade 9-12: Explain the diversity of human characteristics in major geographic realms and AL regions of the world. Examples: North America, Grade 7: Describe the relationship Middle and South America, Europe, Russia, Africa, between locations of resources and Southwest Asia, Middle East, South Asia, East patterns of population distribution in the Asia, Pacific. Tracing global and regional effects RECOMMENDED: Western Hemisphere. Example, fish from RECOMMENDED World of political and economic alliances such as NATO, Geography Canada. Geography OPEC, and NAFTA. Grade 12: Comparison of the development and characteristics of the world’s traditional, command, and market economies. Contrasting AL Grade 5: Describe how geography and economic systems of various countries with the natural resources of different regions of market system of the United States. Examples: North America impacted different groups of Japan, Germany, United Kingdom, China, Cuba, Native Americans. Describe cultures, North Korea, Mexico, Canada, transitioning governments, economies, and religions of economies of the former Soviet Union. Explain different groups of Native Americans. basic elements of international trade. Examples: Identify the issues that led to the War of Grade 7: Compare the government of the OPEC, General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade SUGGESTED: US 1812. Describe major events occurring during United States with other governmental RECOMMENDED: (GATT), NAFTA, European Economic Community History the War of 1812. -

The Territorial North

The Territorial 11 North Learning Objectives To describe the physical and historical geography of the Territorial North as a basis for understanding the region’s social and econom- ic position in Canada To describe the dual character of the Territorial North (in terms of resource frontier and homeland) To describe the Territorial North’s position as a resource frontier in the core/periphery model To outline the key role Canada’s north plays in geopolitics by discussing Arctic sovereignty To outline the key role played by megaprojects in the region’s development Chapter Overview The Territorial North is Canada’s largest region and the only one to be categorized as a resource frontier in the core/periphery model. Key themes of this chapter include: 1. Remoteness of the Territorial North. 2. Resources within the Territorial North. 3. Recognition of this region as a homeland for Indigenous peoples The Territorial North within Canada and the World The Territorial North comprises 39 per cent of Canada’s area, 0.3 per cent of its GDP, and 0.3 per cent of its population. As a result of its geographic remoteness and dependence on resources, mega- projects in this region have significant implications not only for economic development but also for social conditions and the environment. Physical Geography of the Territorial North The Territorial North extends across four physiographic regions and two climate zones. Bone points out that the physical geography of the Territorial North is influenced more by its cold environment than by physical topography (p. 367). It is largely because of the cold environment that northern ecosystems are frequently described as “fragile” or “delicate,” and require prolonged periods of time to recover from human activity. -

Human Geography of Canada: Developing a Vast Wilderness

Chapter 7 Guided Notes _________________________________________________________________________________________ NAME Human Geography of Canada: Developing a Vast Wilderness Three major groups in Canada—the native peoples, the French, and the English—have melded into a diverse and economically strong nation. Section 1: History and Government of Canada French and British settlement greatly influenced Canada’s political development. Canada’s size and climate affected economic growth and population distribution. The First Settlers and Colonial Rivalry Early Peoples After Ice Age, migrants cross Arctic land bridge from Asia o ancestors of Arctic Inuit (Eskimos); North American Indians to south Vikings found Vinland (Newfoundland) about A.D. 1000; later abandon Colonization by France and Britain French explorers claim much of Canada in 1500–1600s as “New France”; British settlers colonize the Atlantic Coast Steps Toward Unity Establishing the Dominion of Canada In 1791 Britain creates two political units called provinces o Upper Canada (later, Ontario): English-speaking, Protestant; Lower Canada (Quebec): French-speaking, Roman Catholic Rupert’s Land a northern area owned by fur-trading company Immigrants arrive, cities develop: Quebec City, Montreal, Toronto o railways, canals are built as explorers seek better fur-trading areas Continental Expansion and Development From the Atlantic to the Pacific In 1885 a transcontinental railroad goes from Montreal to Vancouver o European immigrants arrive and Yukon gold brings fortune hunters; -

Canada: Physical Background

Canada: Physical Background Why look at Canada’s Physical Geography? • It helps shape the human geography of Canada – And its regions Reading • Take a look at any traditional textbook in the geography of Canada – There is usually a chapter on physical geography – Chapter 2 from Bob Bone’s book is copied and on reserve in GRC S403 Ross Canada • Is built on continental crust • Therefore contains very ancient rocks • Has a long and very complex geological history • Is most geologically active around its edges • We live here in one of its quieter middle bits – Life in the slow lane Geologic Provinces • Shield (continental crust) • Sedimentary platforms • Fold mountain belts • Arctic coastal plain Geologic Time Scale Period Millions of Regions formed Years Ago Quaternary 2-0 Great Lakes Cenozoic 100-0 Cordillera, Inuitian Mesozoic 250-100 Interior plains Paleozoic 600-250 Appalachian uplands, Arctic lands Precambrian 3500-600 Shield Canadian Shield • Ancient (3500 million years +) • Crystalline base of continent • Formed at great depth & pressure – faulted, folded, flowed – metamorphic rocks: gneiss – from 5+ phases of mountain building • Poor agricultural soils Shield Rocks • Formed in an era of rather small continents – 1/10th the size of present-day continents or less • North American shield: – Formed out of 7 ‘provinces’ – Each with separate belts/terranes Shield Rocks • The zones of mountain building (orogens) were smaller too • Plate tectonics operated – But in many ways differently than today Nain Province Ungava, Quebec Churchill province -

Geography-Of-Canada-Stations-Activity-Booklet

Geography of Canada Station 1 1. What 2 hemispheres is Canada located in? • ________________________________ • ________________________________ 2. What 3 oceans is Canada surrounded by? • ________________________________ • ________________________________ • ________________________________ 3. What country is located to the South of Canada? • ________________________________ 4. What 2 factors make trade & travel easy for Canadians? • ________________________________ • ________________________________ 5. Locate & Label Canada, the United States, the Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, & the Arctic Ocean. Station 2 1. What type of climate does the southeastern part of Canada have? • ________________________________ 2. Humid Continental Climate has ______________ to ________________ summers & ________________winters. 3. Why does Canada have a low population compared to the size of the country? • _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ 4. Shade in the area with a Polar Tundra Climate in dark blue. 5. Shade in the area with COLD & SNOWY climate in light blue Station 3 1. How many lakes make up the Great Lakes? 2. Complete the HOMES Acronym. • H________________________ • O ________________________ • M ________________________ • E ________________________ • S ________________________ 3. Why is this area known as the «industrial heartland» of the North American continent? 4. Most of Canada’s ____________________ lives in this region. 5. Locate & LABEL the ALL of the Great Lakes. 6. Color them -

Mapping Geographical Education in Canada: Geography in the Elementary and Secondary Curriculum Across Canada

Review of International Geographical Education Online © RIGEO Vol. 2, No. 1, Spring 2012 Mapping Geographical Education in Canada: Geography in the Elementary and Secondary Curriculum across Canada Allison SEGEREN1 University of Western Ontario, London, Canada Abstract This project builds upon previous surveys of geographical education across Canada completed by Baine (1991) and Mansfield (2005). The purpose of this study was to survey the geography curriculum in each of the ten provinces and three territories in Canada. Geography and social studies curriculum guidelines for grades 1 through 12 were collected in each regional jurisdiction across Canada. A summary of key information was recorded for each grade in each jurisdiction; included were course title, prominent themes, and units of instruction. The overall goal during data analysis was to draw a series of comparisons between the general trends discovered by Baine (1991) and Mansfield (2005) and the patterns that emerged from geography curriculum documents as of 2009. The data suggested that, with the exception of Ontario, all provinces and territories have de-emphasized or deleted specific courses or units in geographical education. In a social studies curriculum dominated by history and civics, there is often little stated emphasis on geographical content, concepts, or skills in grades 1 through 12. Keywords: geographical education, geography, social studies, curriculum, Canada This project was presented at the Annual Conference of the Ontario Association for Geographic and Environmental Education, Ottawa, Ontario, October 30, 2010. 1 PhD candidate, University of Western Ontario, London Canada, 1137 Western Road, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 1G7, E-mail: asegeren[at]uwo.ca © Review of International Geographical Education Online RIGEO 2012 ISSN: 2146-0353 www.rigeo.org Review of International Geographical Education Online © RIGEO Vol. -

Landform Regions

Geography of Canada CGC 1DI (Academic) Canada’s Landform Regions Reference: Making Connections, Chapter 12 Using the textbook as a reference, fill in the missing information in the paragraphs below. The Canadian Shield The shield is under most of Canada and parts of the . More than km of Canada is covered by it. It contains some of the world’s oldest rocks ( years old). Two types of rock; and form most of the shield. These rocks contain minerals such as and in great quantities. Because of this, the Canadian Shield is often called the “storehouse of “. Minerals were deposited in the shield as slowly intruded and cooled. Many cities and towns, such as in Ontario or in the Northwest Territories, rely on the mining industry for jobs. The shield is ill suited for due to thin soils, but is ideal for . The plentiful water flow has made the region an excellent source of energy. Since the outer portion of the shield is lower than the centre (similar to a ), most of the rivers flow towards its centre and into The Lowlands Surrounding the Canadian Shield are the following three lowland regions: a) b) c) The sediments that form the bedrock under these regions were from the Shield. The weight of the upper layers of sediments compressed the lower layers of sediments into rock. Geography of Canada CGC 1DI (Academic) Interior Plains The Interior Plains are part of the Great Plains of North America that stretch from the Ocean to the . The Interior Plains were often covered by shallow seas. During the era, coral reefs formed close to the surface of these seas. -

8 Western Canada

Western Canada 8 Learning Objectives To describe the physical and historical geography of Western Canada as a basis for understanding the region’s social and economic posi- tion in Canada To emphasize the role of environmental challenges in agricultural regions and the oil sands industry To outline the transformation of Western Canada’s economy from agricultural frontier to “rapidly growing region” To highlight Western Canada’s industrial sector and trends toward more processing of agricultural products, a larger service sector, and growing urban centres with knowledge-based research clusters To describe Western Canada’s resource sector and complexities re- lated to pipelines, pollution, government approaches, and promises. Chapter Overview The geographic dimensions and importance of Western Canada are outlined in Chapter 8 and these dominant themes emerge: 1. Tremendous economic growth in this region in the past decade, followed by an end of the re- source boom in 2014. 2. The region’s continental position results in higher transportation costs in accessing global markets. 3. The continuing role of agriculture as an economic anchor for Western Canada. 4. Alberta’s oil sands and mining activities have brought prosperity to the region in addition to environmental challenges. Western Canada within Canada Western Canada is a rapidly growing region, ranking second in GDP and third in population size of the six geographic regions. Western Canada’s Population Of Western Canada’s 6.7 million people (2016), the Indigenous population forms nearly 10 per cent. First Nation reserves and the urban Indigenous population are increasing in population. Western Canada’s Physical Geography The physical geography of Western Canada features two major physiographic regions—the Interior Plains and the Canadian Shield—and two minor ones—the Hudson Bay Lowland and the Cordille- ra. -

Canadian Curriculum Guide 2016

he comparisons with the United States are frequent, however the differences and distinct personalities are exciting. Like the U.S., Canada is a very young country in comparison to the rest of the world. Like the U.S, it has a British heritage, but the French were there first and are one of the two founding nations. Both countries became new homes to the world’s immigrants, creating an exciting display of culture and style. Both countries were also built on a foundation of First Nations people, those who originally inhabited their soils. We not only share the world’s longest unprotected border with our neighbor to the north, we also share many values, diversity, celebrations, and great pride and patriotism. We share concerns for other nations, and a willingness to extend a hand. Our differences make our friendship all the more intriguing. Our bonds grow as we explore and appreciate their natural beauty of waterfalls, glaciers, abundant wildlife and breathtaking vistas. We’re similar in size, however with a fraction of our population, they make us envious of their open spaces and relaxed attitudes. Canada is so familiar, so safe… yet so fascinatingly. Who wouldn’t be drawn by strolls throughout the ancient city of Quebec, hiking or biking in Alberta or British Columbia, breathing the fresh air of Nova Scotia sweeping in from the Atlantic, or setting sail from Prince Edward Island? How can you not envy a neighbor who furnishes ten times more breathing room and natural beauty per person than we do? How cool to have a neighbor with one city that boasts as many polar bears as residents. -

UNIT1 the Geography of Canada

01_horizons2e_9th.qxp 3/31/09 3:03 PM Page 2 UNIT The Geography of 1 Canada IN THIS UNIT This unit helps you investigate these questions. ● What physical and natural forces have shaped Canada? ● Why is Canada a country of such great natural diversity? ● How have physical and natural forces shaped the culture and identity of Canadians? ● How have communities in Canada adapted to, and been affected by, geographical changes? Natural forces. Plate tectonics—movements within and on the earth’s crust—formed the mountains of Canada. Mount Robson is the highest mountain in the Rockies. It was eroded and sculpted by glaciers into the landscape we see today. Do you think mountains like this one might change in the future? 2 01_horizons2e_9th.qxp 3/31/09 3:03 PM Page 3 Nature’s highways. Melting water from glaciers and rivers shaped the landscapes of Canada. Aboriginal peoples, and later fur traders and explorers, used the rivers to travel across the country. Changes. The geography of Canada was changed as A smaller world. Modern communication has bridged colonization spread from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific the distances of what early explorers called “the great lone Ocean. As newcomers grew in number, the landscape was land.” The identity of Canadians has been shaped by changed even further. Will these changes continue? Canada’s size and landscape. As the country “shrinks” as a result of new technology, will an identity so closely linked to the land be lost? 01_horizons2e_9th.qxp 3/31/09 3:03 PM Page 4 1 Canada: Making Connections Chapter Outcomes In this chapter, you will examine the geography of Canada. -

9 British Columbia

British Columbia 9 Learning Objectives To describe the physical and historical geography of BC as a basis for understanding the region’s economic and social position in Canada To demonstrate that BC’s significance to Canada’s economic system is increasing To illustrate the growing importance of knowledge-based activities, innovative manufacturing, and tourism in the BC economy To illustrate some decline in the resource-based industries even as they remain strong and important to the BC economy To describe environmental challenges in BC and tensions that can emerge in relation to environment and industry. Chapter Overview Chapter 9 outlines the geographic dimensions and importance of another single-province region: British Columbia. The chapter focuses on three main themes: 1. British Columbia as “an emerging giant within Canada’s economic system” (p. 285). 2. The key role that resources have played in shaping the region’s economy. 3. The emergence of an urban-based economy lead by knowledge-based activities, tourism, and global trade. British Columbia within Canada Steady economic and population growth have strengthened British Columbia’s regional geopolitical position within Canada. The province includes the massive Western Cordillera and the energy-rich northeastern portion of Interior Plains. Population With nearly 5 million people, British Columbia comprises just over 13 per cent of Canada’s popu- lation, with an urban core in the Lower Mainland. British Columbia’s Physical Geography British Columbia’s physical geography, as Bone notes, is “perhaps the region’s greatest natural asset” (p. 288). In terms of both climate and physiography, BC’s diversity is unmatched.