2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abacca Mosaic Virus

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Common Pines of Massachusetts by GORDON P

Common Pines of Massachusetts by GORDON P. DEWOLF, JR. We tend to take wood for granted; or, if we are very modem, to assume that steel, aluminum, and plastics have made wood obsolete. Such is not the case, and, although wood may not seem very important in a stainless steel and glass office build- ing, it still provides shelter and comfort for most of us. To the English colonists who settled New England, wood was a vital commodity that shaped their future in an alien land. The trees that they encountered were usually in vast tracts, and some were totally different from any they had known in England. - The colonists’ need to clear land for gardens and pastures, combined with the fact that Spain, Portugal and the British West Indies were experiencing a lumber shortage, encouraged the development of a thriving export trade in timber products. White oak barrel staves to make barrels for wine, molasses, and rum were one of the most valuable New England exports. Old England seemed to be interested in only one commodity, how- ever : white pine logs for masts. Until the settlement of the American colonies, Britain had obtained most of her ship building timber either locally or from various ports around the Baltic Sea. With the growth of popu- lation and empire, the numbers and sizes of ships increased. One of the most serious problems for the ship builder was the availability of suitable masts. At the end of the Colonial period a First Rate ship carrying 120 guns required a main mast 40 inches in diameter and 40 yards (120 ft.) long. -

FSC National Risk Assessment

FSC National Risk Assessment for the Russian Federation DEVELOPED ACCORDING TO PROCEDURE FSC-PRO-60-002 V3-0 Version V1-0 Code FSC-NRA-RU National approval National decision body: Coordination Council, Association NRG Date: 04 June 2018 International approval FSC International Center, Performance and Standards Unit Date: 11 December 2018 International contact Name: Tatiana Diukova E-mail address: [email protected] Period of validity Date of approval: 11 December 2018 Valid until: (date of approval + 5 years) Body responsible for NRA FSC Russia, [email protected], [email protected] maintenance FSC-NRA-RU V1-0 NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION 2018 – 1 of 78 – Contents Risk designations in finalized risk assessments for the Russian Federation ................................................. 3 1 Background information ........................................................................................................... 4 2 List of experts involved in risk assessment and their contact details ........................................ 6 3 National risk assessment maintenance .................................................................................... 7 4 Complaints and disputes regarding the approved National Risk Assessment ........................... 7 5 List of key stakeholders for consultation ................................................................................... 8 6 List of abbreviations and Russian transliterated terms* used ................................................... 8 7 Risk assessments -

Decisions Adopted During the 42Nd Session of the World Heritage Committee

World Heritage 42 COM WHC/18/42.COM/18 Manama, 4 July 2018 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Forty-second session Manama, Bahrain 24 June – 4 July 2018 Decisions adopted during the 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee (Manama, 2018) Table of Contents 2. ADMISSION OF OBSERVERS .......................................................................................................... 4 3. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA AND THE TIMETABLE .................................................................... 4 3A. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA ........................................................................................................... 4 3B. PROVISIONAL TIMETABLE OF THE 42ND SESSION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE (MANAMA, 2018) ................................................................................................................................ 4 4. REPORT OF THE RAPPORTEUR OF THE 41ST SESSION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE (KRAKOW, 2017) ......................................................................................................... 5 5. REPORTS OF THE WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE AND THE ADVISORY BODIES ....................... 5 5A. REPORT OF THE WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE ON ITS ACTIVITIES AND THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE’S DECISIONS ............................................................... 5 5B. REPORTS OF THE ADVISORY BODIES .......................................................................................... -

Pines in the Arboretum

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MtJ ARBORETUM REVIEW No. 32-198 PETER C. MOE Pines in the Arboretum Pines are probably the best known of the conifers native to The genus Pinus is divided into hard and soft pines based on the northern hemisphere. They occur naturally from the up the hardness of wood, fundamental leaf anatomy, and other lands in the tropics to the limits of tree growth near the Arctic characteristics. The soft or white pines usually have needles in Circle and are widely grown throughout the world for timber clusters of five with one vascular bundle visible in cross sec and as ornamentals. In Minnesota we are limited by our cli tions. Most hard pines have needles in clusters of two or three mate to the more cold hardy species. This review will be with two vascular bundles visible in cross sections. For the limited to these hardy species, their cultivars, and a few hy discussion here, however, this natural division will be ignored brids that are being evaluated at the Arboretum. and an alphabetical listing of species will be used. Where neces Pines are readily distinguished from other common conifers sary for clarity, reference will be made to the proper groups by their needle-like leaves borne in clusters of two to five, of particular species. spirally arranged on the stem. Spruce (Picea) and fir (Abies), Of the more than 90 species of pine, the following 31 are or for example, bear single leaves spirally arranged. Larch (Larix) have been grown at the Arboretum. It should be noted that and true cedar (Cedrus) bear their leaves in a dense cluster of many of the following comments and recommendations are indefinite number, whereas juniper (Juniperus) and arborvitae based primarily on observations made at the University of (Thuja) and their related genera usually bear scalelikie or nee Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, and plant performance dlelike leaves that are opposite or borne in groups of three. -

Effect of Pine Fruits on Some Biological Changes in Hypercholesterolemia

Effect of pine fruits on some biological changes in hypercholesterolemia rats induced Omar Ahmed Emam, Ahmed Mohamed Gaafer , Ghada Mahmoud Elbassiony and Mashael Mobard Ahmed El-Fadly Effect of pine fruits on some biological changes in hypercholesterolemia rats induced Omar Ahmed Emam1, Ahmed Mohamed Gaafer2, Ghada Mahmoud Elbassiony1 and Mashael Mobard Ahmed El-Fadly1 1Department of Home Economics, Faculty of Specific Education, Benha University, Benha, Egypt; 2Research Institute of Food Technology , Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt Abstract his study aimed to determine chemical composition, antioxidant contents, fatty acids of pine nut fruits and also, the effect of pine powder with different ratio T (3, 6 and 9%) on biochemical changes of hypercholesterolemic rats. Biological evaluation of growth performance, Lipid profile, serum protein, blood sugars, liver and kidney functions were also studied. The obtained results indicated that pine nut fruits are considered as a good source of oils, crude fibers, ash, protein, soluble carbohydrates, total energy polyphenols and flavonoids. Besides, it is a rich source of unsaturated fatty acids mainly, linoleic acid (C18:2) which represent more than half amount of total fatty acids. Biological evaluations showed that pine nut was significantly decreased (P ≤ 0.05) of body weight, total lipids, triglycerides, LDL, HDL, VLDL cholesterol of serum hypercholesterolemic rats as compared with positive group of rats Also, it caused significant decrease (P ≤ 0.05) in liver enzyme (AST, ALT and ALP) and kidney parameters (urea, uric acid and creatinine, i.e. improved liver and kidney functions as compared with positive control group. Meanwhile, both total protein and albumin were increased. -

Last Chance Tourism

Ekoloji 27(106): 441-447 (2018) Development Perspectives of “Last Chance To u r i s m ” as One of the Directions of Ecological To u r i s m Oleg A. Bunakov 1*, Natalia A. Zaitseva 2, Anna A. Larionova 3, Nataliia V. Zigern-Korn 4, Marina A. Zhukova 5, Vadim A. Zhukov 5, Alexey D. Chudnovskiy 5 1 Kazan Federal University, Kazan, RUSSIA 2 Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, Moscow, RUSSIA 3 Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Moscow, RUSSIA 4 Saint-Petersburg State University, Saint-Petersburg, RUSSIA 5 State University of Management, Moscow, RUSSIA * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The relevance of researching the problems and prospects for the development of this tourism type as “Last Chance Tourism” as well as within the framework of ecological tourism, is explained by the importance of preserving tourist territories and objects of display in order to achieve the goals of an effective combination of ecological and economic components for the benefit of the general territory development. The purpose of this study is to determine the development prospects of the Last Chance Tourism, as one of the directions of ecological tourism. To implement this study, the authors of the article used the methods of data systematization, content analysis, expert assessments and other scientific approaches, which allow to comprehensively consider the problem under study. The authors propose a refined definition of “eco- tourism” by referring to the results of the analysis of existing research. We give the characteristics of tourists, who are attracted by the objects of “Last Chance Tourism”. -

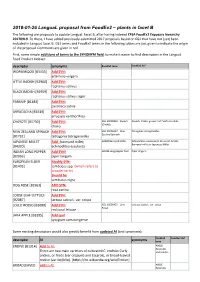

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Part B Other Products Referred to in Article 2(1)

Part B Other products referred to in Article 2(1) Other products References to Part A to which the same MRLs apply (1) Main product of the group or subgroup Code number Category Code number or Common names/synonyms Scientific names Name of the group or subgroup 0110010-001 Natsudaidais Citrus natsudaidai 0110010-002 Shaddocks/pomelos Citrus maxima; syn: Citrus grandis 0110010-003 Sweeties/oroblancos Citrus grandis x Citrus paradisi 0110010 Grapefruits 0110010-004 Tangelolos Citrus paradisi x tangelo 0110010-005 Tangelos (except minneolas)/Ugli® Citrus tangelo 0110010-990 Other hybrids of Citrus paradisi , not elsewhere mentioned 0110020-001 Bergamots Citrus bergamia 0110020-002 Bitter oranges/sour oranges Citrus aurantium 0110020-003 Blood oranges Citrus sinensis 0110020 Oranges 0110020-004 Cara caras Citrus sinensis 0110020-005 Chinottos Citrus myrtifolia 0110020-006 Trifoliate oranges Poncirus trifoliata 0110020-990 Other hybrids of Citrus sinensis, not elsewhere mentioned 0110030-001 Buddha's hands/Buddha's fingers Citrus medica var. sarcodactyla 0110030 Lemons 0110030-002 Citrons Citrus medica 0110040-001 Indian sweet limes/Palestine sweet limes Citrus limettioides 0110040-002 Kaffir limes Citrus hystrix 0110040 Limes 0110040-003 Sweet limes/mosambis Citrus limetta 0110040-004 Tahiti limes Citrus latifolia 0110040-005 Limequats Citrus aurantiifolia x Fortunella spp. 0110050-001 Calamondins Citrus madurensis 0110050-002 Clementines Citrus clementina 0110050-003 Cleopatra mandarins Citrus reshni 0110050-004 Minneolas Citrus tangelo 0110050 Mandarins 0110050-005 Satsumas/clausellinas Citrus unshiu 0110050-006 Tangerines/dancy mandarins Citrus tangerina 0110050-007 Tangors Citrus nobilis 0110050-990 Other hybrids of Citrus reticulata , not elsewhere mentioned 0120010-001 Apricot kernels Armeniaca vulgaris; syn: Prunus armeniaca 0120010-002 Bitter almonds Amygdalus communis var. -

Specializing in Rare and Unique Trees 2015 Catalogue

Whistling Gardens 698 Concession 3, Wilsonville, ON N0E 1Z0 Phone- 519-443-5773 Fax- 519-443-4141 Specializing in Rare and Unique Trees 2015 Catalogue Pot sizes: The number represents the size of the pot ie. #1= 1 gallon, #10 = 10 gallon #1 potted conifers are usually 3-5years old. #10 potted conifers dwarf conifers are between 10 and 15 years old #1 trees= usually seedlings #10 trees= can be several years old anywhere from 5 to 10' tall depending on species and variety. Please ask us on sizes and varieties you are not sure about. Many plants are limited to 1specimen. To reserve your plant(s) a 25% is required. Plants should be picked up by June 15th. Most plants arrive at the gardens by May 10th. Guarantee: We cannot control the weather (good or bad), rodents (big or small), pests (teenie, tiny), poor siting, soil types, lawnmovers, snowplows etc. Plants we carry are expected to grow within the parameters of normal weather conditons. All woody plant purchases are guaranteed from time of purchase to December 1st of current year Any plant not performing or dying in current season will be happily replaced or credited towards a new plant. Please email us if possible with any info needed about our plants. We do not have a phone in the garden centre and I'm rarely in the office. It is very helpful to copy and paste the botanical name of the plant into your Google browser, in most cases, a d Order Item Size Price Description of Pot European White Fir Zone 5 Abies alba Barabit's Spreader 25-30cm #3 $100.00 Abies alba Barabit's Spreader 40cm -

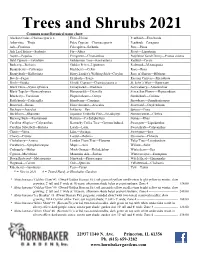

Trees and Shrubs 2021 Common Name/Botanical Name Chart: Alaskan Cedar--Chamaecyparis N

Trees and Shrubs 2021 Common name/Botanical name chart: Alaskan Cedar--Chamaecyparis n. Elm---Ulmus Pearlbush---Exochorda Arborvitae---Thuja False Cypress---Chamaecyparis Peashrub---Caragana Ash---Fraxinus Falsespirea--Sorbaria Pine---Pinus Ash Leaf Spirea---Sorbaria Fir---Abies Privet---Ligustrum Aspen---Populus Fringetree---Chionanthus Purpleleaf Sand Cherry---Prunus cistena Bald Cypress---Taxodium Goldenrain Tree---Koelreuteria Redbud---Cercis Barberry---Berberis Golden Privet--Ligustrum Redwood---Metasequoia Beautyberry---Callicarpa Hackberry---Celtis Rose---Rosa Beautybush---Kolkwitzia Harry Lauder’s Walking Stick--Corylus Rose of Sharon---Hibiscus Beech---Fagus Hemlock---Tsuga Russian Cypress---Microbiota Birch---Betula Hinoki Cypress---Chamaecyparis o. St. John’s Wort---Hypericum Black Gum---Nyssa sylvatica Honeylocust---Gleditsia Serviceberry---Amelanchier Black Tupelo---Nyssa sylvatica Honeysuckle---Diervilla Seven Son Flower---Heptacodium Blueberry-- Vaccinum Hophornbeam---Ostrya Smokebush---Cotinus Bottlebrush---Fothergilla Hornbeam---Carpinus Snowberry---Symphoricarpos Boxwood---Buxus Horsechestnut---Aesculus Sourwood---Oxydendrum Buckeye---Aesculus Inkberry—Ilex Spruce---Picea Buckthorn---Rhamnus Japanese Umbrella Pine---Sciadopitys Summersweet---Clethra Burning Bush---Euonymous Katsura---Cerdidiphyllum Sumac---Rhus Carolina Allspice---Calycanthus Kentucky Coffee Tree---Gymnocladus d. Sweetgum---Liquidambar Carolina Silverbell---Halesia Larch---Larix Sweetshrub---Calycanthus Chaste---Vitex Lilac---Syringa Sweetspire---Itea -

Hidden Lake Gardens Michigan State University 2019 Plant Sale Plant

Hidden Lake Gardens Michigan State University 2019 Plant Sale Plant List **Please Note: All plants listed are subject to availability due to weather conditions, crop failure, or supplier delivery** Vegetables and Herbs Many assorted varieties Annuals Assorted hanging baskets – Proven Winners® Selections Senecio ‘Angel Wings’ Supertunia® ‘Bordeaux’™ Supertunia® ‘Piccaso in Purple’® Supertunia Royale® Plum Wine Gerbera ‘Garvinea Sweet Sunset’ Salvia ‘Black and Bloom’ Coleus ‘Golden Gate’ Stained Glassworks™ Coleus ‘Royalty’ Stained Glassworks™ Coleus ‘Eruption’ Stained Glassworks™ Coleus ‘Luminesce’ Stained Glassworks™ Coleus ‘Great Falls Niagara’ Strobilanthes dyeriana Persian Shield Bidens ferulifolia ‘Bee Alive’ Bidens ferulifolia ‘Bee Happy’ Bidens ferulifolia ‘Sun Drop Compact’ Zinnia Zahara™ Lantana Lucky™ Angelonia angustifolia Archangel™ Portulaca ColorBlast™ ‘Watermelon Punch’ Perennials Achillea ‘Pomegranate’ Aconitum arendsii Agastache ‘Kudos Coral’ Agastache ‘Kudos Mandarin’ Aquilegia ‘Clementine Dark Purple’ Aquilegia ‘Clementine Salmon Rose’ Armeria maritima ‘Splendens’ Asclepias tuberosa Astilbe ‘Montgomery’ Astilbe ‘Visions’ (purple) Baptisia ‘Lactea’ Baptisia ‘Pink Lemonade’ Bergenia ‘Bressingham Ruby’ Bergenia ‘Sakura’ Brunnera macrophylla ‘Alexander’s Great’ Brunnera macrophylla ‘Jack Frost’ Brunnera macrophylla ‘Sea Heart’ Centaurea montana Ceratostigma plumbaginoides Chelone ‘Hot Lips’ Coreopsis ‘American Dream’ Coreopsis ‘Big Bang Galaxy’ Crocosmia ‘Lucifer’ Dianthus ‘Firewitch’ Dianthus x ‘Kahori’ Dicentra ‘Fire Island’