Common Pines of Massachusetts by GORDON P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abacca Mosaic Virus

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Pines in the Arboretum

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MtJ ARBORETUM REVIEW No. 32-198 PETER C. MOE Pines in the Arboretum Pines are probably the best known of the conifers native to The genus Pinus is divided into hard and soft pines based on the northern hemisphere. They occur naturally from the up the hardness of wood, fundamental leaf anatomy, and other lands in the tropics to the limits of tree growth near the Arctic characteristics. The soft or white pines usually have needles in Circle and are widely grown throughout the world for timber clusters of five with one vascular bundle visible in cross sec and as ornamentals. In Minnesota we are limited by our cli tions. Most hard pines have needles in clusters of two or three mate to the more cold hardy species. This review will be with two vascular bundles visible in cross sections. For the limited to these hardy species, their cultivars, and a few hy discussion here, however, this natural division will be ignored brids that are being evaluated at the Arboretum. and an alphabetical listing of species will be used. Where neces Pines are readily distinguished from other common conifers sary for clarity, reference will be made to the proper groups by their needle-like leaves borne in clusters of two to five, of particular species. spirally arranged on the stem. Spruce (Picea) and fir (Abies), Of the more than 90 species of pine, the following 31 are or for example, bear single leaves spirally arranged. Larch (Larix) have been grown at the Arboretum. It should be noted that and true cedar (Cedrus) bear their leaves in a dense cluster of many of the following comments and recommendations are indefinite number, whereas juniper (Juniperus) and arborvitae based primarily on observations made at the University of (Thuja) and their related genera usually bear scalelikie or nee Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, and plant performance dlelike leaves that are opposite or borne in groups of three. -

Effect of Pine Fruits on Some Biological Changes in Hypercholesterolemia

Effect of pine fruits on some biological changes in hypercholesterolemia rats induced Omar Ahmed Emam, Ahmed Mohamed Gaafer , Ghada Mahmoud Elbassiony and Mashael Mobard Ahmed El-Fadly Effect of pine fruits on some biological changes in hypercholesterolemia rats induced Omar Ahmed Emam1, Ahmed Mohamed Gaafer2, Ghada Mahmoud Elbassiony1 and Mashael Mobard Ahmed El-Fadly1 1Department of Home Economics, Faculty of Specific Education, Benha University, Benha, Egypt; 2Research Institute of Food Technology , Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt Abstract his study aimed to determine chemical composition, antioxidant contents, fatty acids of pine nut fruits and also, the effect of pine powder with different ratio T (3, 6 and 9%) on biochemical changes of hypercholesterolemic rats. Biological evaluation of growth performance, Lipid profile, serum protein, blood sugars, liver and kidney functions were also studied. The obtained results indicated that pine nut fruits are considered as a good source of oils, crude fibers, ash, protein, soluble carbohydrates, total energy polyphenols and flavonoids. Besides, it is a rich source of unsaturated fatty acids mainly, linoleic acid (C18:2) which represent more than half amount of total fatty acids. Biological evaluations showed that pine nut was significantly decreased (P ≤ 0.05) of body weight, total lipids, triglycerides, LDL, HDL, VLDL cholesterol of serum hypercholesterolemic rats as compared with positive group of rats Also, it caused significant decrease (P ≤ 0.05) in liver enzyme (AST, ALT and ALP) and kidney parameters (urea, uric acid and creatinine, i.e. improved liver and kidney functions as compared with positive control group. Meanwhile, both total protein and albumin were increased. -

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Part B Other Products Referred to in Article 2(1)

Part B Other products referred to in Article 2(1) Other products References to Part A to which the same MRLs apply (1) Main product of the group or subgroup Code number Category Code number or Common names/synonyms Scientific names Name of the group or subgroup 0110010-001 Natsudaidais Citrus natsudaidai 0110010-002 Shaddocks/pomelos Citrus maxima; syn: Citrus grandis 0110010-003 Sweeties/oroblancos Citrus grandis x Citrus paradisi 0110010 Grapefruits 0110010-004 Tangelolos Citrus paradisi x tangelo 0110010-005 Tangelos (except minneolas)/Ugli® Citrus tangelo 0110010-990 Other hybrids of Citrus paradisi , not elsewhere mentioned 0110020-001 Bergamots Citrus bergamia 0110020-002 Bitter oranges/sour oranges Citrus aurantium 0110020-003 Blood oranges Citrus sinensis 0110020 Oranges 0110020-004 Cara caras Citrus sinensis 0110020-005 Chinottos Citrus myrtifolia 0110020-006 Trifoliate oranges Poncirus trifoliata 0110020-990 Other hybrids of Citrus sinensis, not elsewhere mentioned 0110030-001 Buddha's hands/Buddha's fingers Citrus medica var. sarcodactyla 0110030 Lemons 0110030-002 Citrons Citrus medica 0110040-001 Indian sweet limes/Palestine sweet limes Citrus limettioides 0110040-002 Kaffir limes Citrus hystrix 0110040 Limes 0110040-003 Sweet limes/mosambis Citrus limetta 0110040-004 Tahiti limes Citrus latifolia 0110040-005 Limequats Citrus aurantiifolia x Fortunella spp. 0110050-001 Calamondins Citrus madurensis 0110050-002 Clementines Citrus clementina 0110050-003 Cleopatra mandarins Citrus reshni 0110050-004 Minneolas Citrus tangelo 0110050 Mandarins 0110050-005 Satsumas/clausellinas Citrus unshiu 0110050-006 Tangerines/dancy mandarins Citrus tangerina 0110050-007 Tangors Citrus nobilis 0110050-990 Other hybrids of Citrus reticulata , not elsewhere mentioned 0120010-001 Apricot kernels Armeniaca vulgaris; syn: Prunus armeniaca 0120010-002 Bitter almonds Amygdalus communis var. -

Specializing in Rare and Unique Trees 2015 Catalogue

Whistling Gardens 698 Concession 3, Wilsonville, ON N0E 1Z0 Phone- 519-443-5773 Fax- 519-443-4141 Specializing in Rare and Unique Trees 2015 Catalogue Pot sizes: The number represents the size of the pot ie. #1= 1 gallon, #10 = 10 gallon #1 potted conifers are usually 3-5years old. #10 potted conifers dwarf conifers are between 10 and 15 years old #1 trees= usually seedlings #10 trees= can be several years old anywhere from 5 to 10' tall depending on species and variety. Please ask us on sizes and varieties you are not sure about. Many plants are limited to 1specimen. To reserve your plant(s) a 25% is required. Plants should be picked up by June 15th. Most plants arrive at the gardens by May 10th. Guarantee: We cannot control the weather (good or bad), rodents (big or small), pests (teenie, tiny), poor siting, soil types, lawnmovers, snowplows etc. Plants we carry are expected to grow within the parameters of normal weather conditons. All woody plant purchases are guaranteed from time of purchase to December 1st of current year Any plant not performing or dying in current season will be happily replaced or credited towards a new plant. Please email us if possible with any info needed about our plants. We do not have a phone in the garden centre and I'm rarely in the office. It is very helpful to copy and paste the botanical name of the plant into your Google browser, in most cases, a d Order Item Size Price Description of Pot European White Fir Zone 5 Abies alba Barabit's Spreader 25-30cm #3 $100.00 Abies alba Barabit's Spreader 40cm -

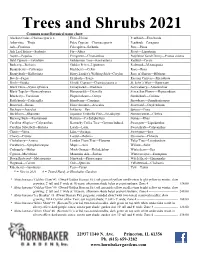

Trees and Shrubs 2021 Common Name/Botanical Name Chart: Alaskan Cedar--Chamaecyparis N

Trees and Shrubs 2021 Common name/Botanical name chart: Alaskan Cedar--Chamaecyparis n. Elm---Ulmus Pearlbush---Exochorda Arborvitae---Thuja False Cypress---Chamaecyparis Peashrub---Caragana Ash---Fraxinus Falsespirea--Sorbaria Pine---Pinus Ash Leaf Spirea---Sorbaria Fir---Abies Privet---Ligustrum Aspen---Populus Fringetree---Chionanthus Purpleleaf Sand Cherry---Prunus cistena Bald Cypress---Taxodium Goldenrain Tree---Koelreuteria Redbud---Cercis Barberry---Berberis Golden Privet--Ligustrum Redwood---Metasequoia Beautyberry---Callicarpa Hackberry---Celtis Rose---Rosa Beautybush---Kolkwitzia Harry Lauder’s Walking Stick--Corylus Rose of Sharon---Hibiscus Beech---Fagus Hemlock---Tsuga Russian Cypress---Microbiota Birch---Betula Hinoki Cypress---Chamaecyparis o. St. John’s Wort---Hypericum Black Gum---Nyssa sylvatica Honeylocust---Gleditsia Serviceberry---Amelanchier Black Tupelo---Nyssa sylvatica Honeysuckle---Diervilla Seven Son Flower---Heptacodium Blueberry-- Vaccinum Hophornbeam---Ostrya Smokebush---Cotinus Bottlebrush---Fothergilla Hornbeam---Carpinus Snowberry---Symphoricarpos Boxwood---Buxus Horsechestnut---Aesculus Sourwood---Oxydendrum Buckeye---Aesculus Inkberry—Ilex Spruce---Picea Buckthorn---Rhamnus Japanese Umbrella Pine---Sciadopitys Summersweet---Clethra Burning Bush---Euonymous Katsura---Cerdidiphyllum Sumac---Rhus Carolina Allspice---Calycanthus Kentucky Coffee Tree---Gymnocladus d. Sweetgum---Liquidambar Carolina Silverbell---Halesia Larch---Larix Sweetshrub---Calycanthus Chaste---Vitex Lilac---Syringa Sweetspire---Itea -

Hidden Lake Gardens Michigan State University 2019 Plant Sale Plant

Hidden Lake Gardens Michigan State University 2019 Plant Sale Plant List **Please Note: All plants listed are subject to availability due to weather conditions, crop failure, or supplier delivery** Vegetables and Herbs Many assorted varieties Annuals Assorted hanging baskets – Proven Winners® Selections Senecio ‘Angel Wings’ Supertunia® ‘Bordeaux’™ Supertunia® ‘Piccaso in Purple’® Supertunia Royale® Plum Wine Gerbera ‘Garvinea Sweet Sunset’ Salvia ‘Black and Bloom’ Coleus ‘Golden Gate’ Stained Glassworks™ Coleus ‘Royalty’ Stained Glassworks™ Coleus ‘Eruption’ Stained Glassworks™ Coleus ‘Luminesce’ Stained Glassworks™ Coleus ‘Great Falls Niagara’ Strobilanthes dyeriana Persian Shield Bidens ferulifolia ‘Bee Alive’ Bidens ferulifolia ‘Bee Happy’ Bidens ferulifolia ‘Sun Drop Compact’ Zinnia Zahara™ Lantana Lucky™ Angelonia angustifolia Archangel™ Portulaca ColorBlast™ ‘Watermelon Punch’ Perennials Achillea ‘Pomegranate’ Aconitum arendsii Agastache ‘Kudos Coral’ Agastache ‘Kudos Mandarin’ Aquilegia ‘Clementine Dark Purple’ Aquilegia ‘Clementine Salmon Rose’ Armeria maritima ‘Splendens’ Asclepias tuberosa Astilbe ‘Montgomery’ Astilbe ‘Visions’ (purple) Baptisia ‘Lactea’ Baptisia ‘Pink Lemonade’ Bergenia ‘Bressingham Ruby’ Bergenia ‘Sakura’ Brunnera macrophylla ‘Alexander’s Great’ Brunnera macrophylla ‘Jack Frost’ Brunnera macrophylla ‘Sea Heart’ Centaurea montana Ceratostigma plumbaginoides Chelone ‘Hot Lips’ Coreopsis ‘American Dream’ Coreopsis ‘Big Bang Galaxy’ Crocosmia ‘Lucifer’ Dianthus ‘Firewitch’ Dianthus x ‘Kahori’ Dicentra ‘Fire Island’ -

Library of Congress Classification

S AGRICULTURE (GENERAL) S Agriculture (General) Periodicals. By language of publication For works about societies and serial publications of societies see S21+ For general yearbooks see S414 1 English (American) 3 English 5 French 7 German 9 Italian 11 Scandinavian 12 Dutch 13 Slavic 15 Spanish and Portuguese 16.A-Z Other European languages, A-Z Colonial, English, and American see S1+ 18 Polyglot 19 Other languages (not A-Z) 20 History and description of periodicals and societies (General) Documents and other collections Including societies and congresses United States Federal documents Commissioner of Patents 21.A19 Agricultural report Department of Agriculture 21.A2-.A29 Report of the Commissioner or Secretary 21.A3 The official record of the Department of Agriculture 21.A35 Yearbook 21.A37 Agriculture handbook 21.A4-.A49 Circulars 21.A6 Farmers' bulletins 21.A63 Weekly newsletter to crop correspondents 21.A7 Bulletin 21.A74 Agriculture information bulletin 21.A75 Journal of agricultural research 21.A78 Weather, crops, and markets 21.A8-.A99 Other reports 21.A86-.A95 Financial: accounts and disbursements, etc. 21.A86 Estimates of expenditures 21.A87 Expenditures ... Letter from the Secretary of Agriculture 21.A99 Miscellaneous general. By date 21.C8-.C9 History 21.C8 Official 21.C9 Nonofficial Administrative documents; appointments; personnel 21.D2-.D39 Serial publications 21.D4-.D7 Monographs Reports of individual bureaus Bureau of Agricultural Economics see HD1751 Bureau of Biological Survey see QH104+ Bureau of Chemistry see S585 -

Mediterranean Stone Pine for Agroforestry Pine As a Nut Crop and to Analyse Its Potential and Current Challenges

OPTIONS OPTIONS méditerranéennes méditerranéennes Mediterranean Stone Pine SERIES A: Mediterranean Seminars CIHEAM 2013 – Number 105 for Agroforestry Mediterranean Stone Pine Edited by: S. Mutke, M. Piqué, R. Calama for Agroforestry Edited by: S. Mutke, M. Piqué, R. Calama The pine nut, the edible kernel of the Mediterranean stone pine, Pinus pinea, is one of the world’s most expensive nuts. Although well known and planted since antiquity, pine nuts are still collected mainly from natural forests in the Mediterranean countries, and only recently has the crop taken the first steps to domestication as an attractive alternative on rainfed farmland in Mediterranean climate areas, with plantations yielding more pine nuts than the natural forests and contributing to rural development and employment of local communities. The species performs well on poor soils and needs little husbandry, it is affected by few pests or diseases and withstands adverse climatic conditions such as drought and extreme or late frosts. It is light-demanding and hence has potential as a crop in agro forestry systems in Mediterranean climate zones around the world. This publication contains 14 of the contributions presented at the AGROPINE 2011 Meeting, held from 17 to 19 November 2011 in Valladolid (Spain). The Meeting aimed at bringing together the main research groups and potential users in order to gather the current knowledge on Mediterranean stone OPTIONS OPTIONS méditerranéennes Mediterranean Stone Pine for Agroforestry pine as a nut crop and to analyse its potential and current challenges. The presentations and debates méditerranéennes were structured into two scientific sessions dealing with management of stone pine for cone production and on genetic improvement, selection and breeding of this species, and was closed by a round -table discussion on the challenges and opportunities of the pine nut industry and markets. -

Evergreen Trees for the Kansas City Region

THE TREE LIST EVERGREEN TREES FOR THE KANSAS CITY REGION AS RATED BY METROPOLITAN AREA EXPERTS last updated, May 17, 2013 Study by Robert Whitman, ASLA, AICP, LEED AP [email protected] ABOUT THIS STUDY: In 2012, Kansas City region tree experts were asked to provide numerical opinions (0-5 ratings) in each category for evergreen trees they have tested/observed from a master list of 154 evergreen trees. These ratings were averaged to determine the tree ratings for each category. PARTICIPANTS: Tim McDonnell, Community Forester, Kansas Forest Service Alan Branhagen, Director of Horticulture, Powell Gardens Ivan Katzer, Consulting Arborist, (816)765-4241 Chuck Conner, Forester, Missouri Department of Conservation Susan Mertz, Loma Vista Nursery, (913)897-7010 Michael Dougherty, Tree Management Company (913)894-8733 Marvin Snyder, Past President, American Conifer Society Rick Spurgeon, Olathe City Arborist Scott Reiter, Linda Hall Library Don Mann, Loma Vista Nursery, (913)897-7010 Duane Hoover, Horticulturist, Kauffman Memorial Garden Cameron Rees, Skinner Garden Store, (785)233-9657 Chip Winslow, FASLA, KSU Department of Landscape Architecture Mic Mills, Rosehill Gardens, (816)941-4777 Kim Bomberger, Community Forester, Kansas Forest Service Dennis Patton, Johnson County Extension Agent Robert Whitman, Landscape Architect, gouldevans Jason Griffin PhD, KSU John C. Pair Horticultural Center © 2013 Robert Whitman | gouldevans *Please distribute freely* EVERGREEN TREES FOR THE KANSAS CITY REGION AS RATED BY METROPOLITAN AREA EXPERTS -

Genetic Improvement of Pinus Koraiensis in China: Current Situation and Future Prospects

Review Genetic Improvement of Pinus koraiensis in China: Current Situation and Future Prospects Xiang Li 1, Xiao-Ting Liu 1, Jia-Tong Wei 1, Yan Li 1, Mulualem Tigabu 2 and Xi-Yang Zhao 1,* 1 State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding, School of Forestry, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, China; [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (X.-T.L.); [email protected] (J.-T.W.); [email protected] (Y.L.) 2 Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-230 53 Alnarp, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 December 2019; Accepted: 23 January 2020; Published: 28 January 2020 Abstract: Pinus koraiensis (Sieb.et Zucc) is an economically and ecologically important tree species, naturally distributed in northeastern China. Conservation efforts and genetic improvement for this species began in the 1960s and 1980s, with the establishment of several primary seed orchards based on range-wide provenance evaluations. The original breeding objective was to improve growth and wood yield, but during the recent decade, it was redefined to include other traits, such as an enhancement of wood properties, seed oil content, cone yield, and the development of elite provenance with families, clones, and varieties with good tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses. However, improvement processes are slow due to a long breeding cycle, and the number of improved varieties is still low. In this review, we summarize the recent progress in the selective improvement of P. koraiensis varieties, such as elite provenance, family, and clones, using various breeding procedures. We collate information on advances in the improvement of P.