Seoullo 7017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPIK Orientation Information

October 2010 EPIK Orientation Information l Venue: National Institute for International Education(NIIED), Seoul l Period: October 23(Sat) ~ October 28(Thu), 2010 l Placements of the participants: Incheon, Gangwon, Gwangju, Daejoen, Chungbuk, Gyeongbuk, Geyongnam, Busan, Jeju and Jeonbuk POE/MOEs 1. Arrival & Transportation ………...……………..…………………..………...1 2. Lost Luggage Protocol ……………..…………………..………...…………..…..3 3. Before Departing ……………..…………………..………...……………………..…..4 3-1. What to Pack 3-2. Important Note Regarding Money 3-3. Request for Accompanying Family Dependents 4. EPIK Orientation Schedule ……………..…………………..………...…………5 1. Arrival & Transportation 1-1. There will be no Shuttle bus run by NIIED. EPIK successful applicants/teachers via recruiting companies should follow recruiting companies’ instruction. 1-2. EPIK direct applicants who are arriving at the airport Please follow directions below to get to the orientation venue at your arrival at the Incheon Airport. 1) Take a limousine bus from the Incheon Airport. (1st Floor: 5B & 12A, Bus No.: 6011) 2) Get off at the Sungkyunkwan –daehakgyo (Sungkyunkwan University) Bus Stop. ▪ Bus Boarding Section: 12A or 5B ▪ Fare: 9,000 KRW ▪ Runs from 5:45am ~ 22:30pm (departs every 20 ~ 30 minutes) ▪ Bus stop to get off: Hyehwa (Sungkyunkwan University) ▪ Route of Bus 6011: 1. Incheon International airport 6. Muakjae 2. Entrance of World Cup Stadium 7. Gyungbokgung 3. Yonhui Intersection 8. Angukdong 4. Seodaemun District office 9. Changdeokgung 5. Grand Hilton Hotel 10. Sungkyunkwan University Entrance 3) After getting off the bus, you can reach NIIED by taxi within 10 minutes. (Minimum range: 2,400 KRW) 기사님, 이 분을 혜화동 방송통신대 뒤 국립국제교육원으로 모셔주십시오. 감사합니다. 문의 전화 : We will have a complimentary shuttle van service from the Sungkyunkwan University Bus Stop to the NIIED training venue. -

Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-Do & Seoul Metropolitan Area

Gyeongchun line Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-do & Seoul Metropolitan Area Hoeryong Uijeongbu Ganeung Nogyang Yangju Deokgye Deokjeong Jihaeng DongducheonBosan Jungang DongducheonSoyosan Chuncheon Mangwolsa 1 Starting Point Destination Dobongsan 7 Namchuncheon Jangam Dobong Suraksan Gimyujeong Musan Paju Wollong GeumchonGeumneungUnjeong TanhyeonIlsan Banghak Madeul Sanggye Danngogae Gyeongui line Pungsan Gireum Nowon 4 Gangchon 6 Sungshin Baengma Mia Women’s Univ. Suyu Nokcheon Junggye Changdong Baekgyang-ri Dokbawi Ssangmun Goksan Miasamgeori Wolgye Hagye Daehwa Juyeop Jeongbalsan Madu Baekseok Hwajeong Wondang Samsong Jichuk Gupabal Yeonsinnae Bulgwang Nokbeon Hongje Muakjae Hansung Univ. Kwangwoon Gulbongsan Univ. Gongneung 3 Dongnimmun Hwarangdae Bonghwasan Sinnae (not open) Daegok Anam Korea Univ. Wolgok Sangwolgok Dolgoji Taereung Bomun 6 Hangang River Gusan Yeokchon Gyeongbokgung Seokgye Gapyeong Neunggok Hyehwa Sinmun Meokgol Airport line Eungam Anguk Changsin Jongno Hankuk Univ. Junghwa 9 5 of Foreign Studies Haengsin Gwanghwamun 3(sam)-ga Jongno 5(o)-gu Sinseol-dong Jegi-dong Cheongnyangni Incheon Saejeol Int’l Airport Galmae Byeollae Sareung Maseok Dongdaemun Dongmyo Sangbong Toegyewon Geumgok Pyeongnae Sangcheon Banghwa Hoegi Mangu Hopyeong Daeseong-ri Hwajeon Jonggak Yongdu Cheong Pyeong Incheon Int’l Airport Jeungsan Myeonmok Seodaemun Cargo Terminal Gaehwa Gaehwasan Susaek Digital Media City Sindap Gajwa Sagajeong Dongdaemun Guri Sinchon Dosim Unseo Ahyeon Euljiro Euljiro Euljiro History&Culture Park Donong Deokso Paldang Ungilsan Yangsu Chungjeongno City Hall 3(sa)-ga 3(sa)-ga Yangwon Yangjeong World Cup 4(sa)-ga Sindang Yongmasan Gyeyang Gimpo Int’l Airport Stadium Sinwon Airprot Market Sinbanghwa Ewha Womans Geomam Univ. Sangwangsimni Magoknaru Junggok Hangang River Mapo-gu Sinchon Aeogae Dapsimni Songjeong Office Chungmuro Gunja Guksu Seoul Station Cheonggu 5 Yangcheon Hongik Univ. -

Planning for Railway Station Network Sustainability Based on Node–Place Analysis of Local Stations

sustainability Article Planning for Railway Station Network Sustainability Based on Node–Place Analysis of Local Stations Joon-Seok Kim and Nina Shin * College of Business Administration, Sejong University, Seoul 05006, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: We principally focus on evaluating the local and entire network performance of railway stations for sustainable logistics management in South Korea. Specifically, we aim to address the issue of dealing with vulnerability in logistics dependent on the degree of connectivity. To resolve this issue, we investigate (i) the current level of local railway station sustainability performance from the perspectives of the value of the station (node) and the geographical location (place), and (ii) how railway station network management can prepare for imminent internal and external risks. Integrating node–place analysis and social network analysis approaches, we demonstrate a means of assessing (i) local railway station performance by comparing how one station’s value differs from that of other stations, and (ii) overall railway network performance by measuring the degree of connectivity based on the centrality characteristics. Consequently, we recommend improvement in planning orders considering the degree of local performance and network vulnerability for railway station network sustainability. Keywords: railway station; railway network sustainability; local station performance; railway network performance; node place analysis Citation: Kim, J.-S.; Shin, N. Planning for Railway Station Network Sustainability Based on 1. Introduction Node–Place Analysis of Local Stations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4778. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused sudden supply chain disruptions in https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094778 many countries. To prevent the spread of COVID-19 effectively, several countries, such as the UK, France, and China, have placed lockdowns in populated areas. -

SEOUL City Guide

SEOUL city guide Before you go Here are some suggested stays for every wallet size. These are conveniently located near the heart of Seoul, so it’s easy for you to get around! Budget Hotel USD 60/night and below ● Rian Hotel ● Hotel Pop Jongno USD 150/ night and below ● Hotel Skypark Central Myeongdong ● Ibis Ambassador Myeong-dong USD 300/night and below ● Lotte Hotel Seoul ● The Westin Chosun Seoul Before leaving the airport, be sure to pick up the following items. Item Location 4G WiFi Device KT Roaming Center at the following locations Incheon International Airport ● 1/F Gate 6-7, open 24 hours daily ● Gate 4-5 (From 1 Mar 2018), Daily 7am to 10pm ● Gate 10-11, Daily 6am to 10pm 4G SIM Card Incheon Airport International Airport Terminal 2 1st Floor Gate 2-3 KT Roaming Center, open 24 hours daily Gimpo International Airport (Seoul) 1/F Gate 1, Daily 7am to 11pm AREX Incheon Airport Incheon International Airport Terminal 1 Express Train One Way Transportation Center of Incheon Int'l Airport (B1F floor) Information Ticket in Seoul Center Opening hours: Daily, 5am to 10:40pm Incheon International Airport Terminal 2 Transportation Center of Incheon Int'l Airport (B1F floor) Information Center Opening hours: Dail, 5am to 10:40pm Alternatively, you can also exchange your tickets manually at the Express Train Ticket Vending Machine located at the Incheon Airport Station and Seoul Station Korea Rail Pass (KR PASS) Incheon Airport Railroad Information Center Opening hours: Daily, 7am to 9:30pm DAY 1 OVERVIEW Time Activity How To Get There Travel -

Directions to Allen Hall for the Japan-Korea PHENIX Workshop

Directions to Allen Hall for the Japan-Korea PHENIX workshop. Upon arriving in Korea at either Incheon International Airport or Gimpo International Airport, make your way to Seoul Station. If you arrive in Korea at the Incheon International Airport, 1) you can take the Airport Railroad Express (AREX) to Seoul Station. The Express train costs 13,300 won and takes 53 minutes while the Commuter train costs 3,700 won and takes 43 minutes. 2) Or you can take a limousine bus (number 6011) If your flight lands at the Gimpo International Airport, take the AREX Commuter train to Seoul Station. The fare is about 1,200 won and it will take about 38 minutes. Although it is more convenient to take the AREX train since it arrives directly below Seoul Station, it is possible to take subway lines 5 and 9. Once at Seoul Station, please take a taxi to the guest house. ====================================================================== If you want to take airport subway from Inchon, please read this. First, you should take the airport subway. The Inchon airport subway station is connected to the Inchon airport. Figure 1. The rail load from Inchon airport to the Seoul Station] You need to take a train in the Inchon airport station and get off the subway in the Seoul station. After you get off the Seoul Station, you should get out to the exit number 1 (See Figure 2). Then, you can see the number of bus platforms and buildings. If you see the building named Seoul Square, then you are in the right place. -

Table of Contents >

< TABLE OF CONTENTS > 1. Greetings .................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Company Profile ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 A. Overview ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 B. Status of Registration ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 3. Organization .............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 A. Organization chart ............................................................................................................................................................. 8 B. Analysis of Engineers ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 C. List of Professional Engineers......................................................................................................................................... 10 D. Professional Engineer in Civil Eng.(U.S.A) .................................................................................................................. -

Newsletter Newsletter

2017.07 SEOUL TOUR+ NEWSLETTER Seoul, Filled with Fall Romance and Festive Excitement New and Recommended Attractions Must-Go Attractions for Autumn Foliage and Silver Grass in Fall 1 Fall Music Festival 2 Seoul International Dance Festival 2017 3 Korean Traditional Food Culture Center Eeum 4 <Hunminjeongeum, Nanjung Ilgi: Look, Again> Exhibition 5 Special Recommendations Seoullo 7017 Travelers' Cafe 6 Tasty Food in Seongbuk-dong Near Seoul City Wall 7 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics Torch Relay 8 Seoul Jewelry Industry Support Center 2 9 Namsangol Hanok Village 'Namsangol Vacation' 10 2017 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 11 Barrier-free Tours Jongmyo Shrine 12 Seoul Arirang Festival 13 Must-go Attractions in Fall Attractions for Autumn Foliage and Silver Grass Haneul Park at World Cup Park Jeongdok Public Library 95, Haneulgongwon-ro, Mapo-gu, Seoul 48, Bukchon-ro 5-gil, Jongno-gu, Seoul +82-2-300-5501 +82-2-2011-5799 05:00~22:00 (Varies by season) 07:00~23:00 parks.seoul.go.kr/template/sub/worldcuppark.do (Kor) jdlib.sen.go.kr (Kor/Eng) Subway Line 6, World Cup StadiumStation Exit 1, 10 min. on foot Subway Line 3, Anguk Station Exit 1, 10 min. on foot ‣ Introducing must-go Seoul attractions in fall for magnificent autumn foliage and silver grass landscapes ‣ Great places to visit in fall for families and couples touring Seoul Location Details - 2017 Seoul Silver Grass Festival: Oct. 13~19 (scheduled) / Free [Silver Grass] - Greatest festival in fall worthy of its name; held in Oct. each year when silver grass flowers are in full bloom Haneul Park at - Festival open at night to enjoy the relaxing fall mood along with the sunset enveloping over Seoul World Cup Park - Enjoy a blaze of color amid fields of silver grass and the beautiful scenery of Seoul - Spaces for a variety of experiences provided: photo zone, pinwheel street, field of cosmos flowers, etc. -

Seoul Tour+ Vol.5 7 En.Hwp

Contents For the month of July, Seoul Tour+ introduces chances for cool exhibitions amidst sweltering hot weather in leading arts institutions in Seoul as well as summer fashion trends found in the world’s largest container shopping mall. 1 Special exhibition _ Grévin Museum 1 2 Exhibition _ Fernando Botero (Seoul Arts Center) 2 3 Hallyu experience _ Yido 3 4 Container shopping mall _ Common Ground 4 5 Self-photography studio _ Pencil Point Studio 5 6 Special experience _ Noongam: Café in the dark 6 7 Cultural complex space _ Insadong Maru 7 8 Traditional Market _ Namdaemun Market 8 Special1 Special recommendation _ Seoul Culture Night 9 Special2 Special recommendation _ Seoul Drum Festival 10 2015 Seoul Certification Program for High-Quality Tour Special3 11 Package Grévin Museum 1 Place Grévin Museum Address 23 Eulji-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul Phone +82-70-4280-8800 Homepage www.grevinkorea.com Holidays Open 365 days Reservation No reservation required Opening hours 10:00 ~ 19:00 Overview Adults 23,000 won Payment Cash or credit card Person Youths 18,000 won method (including international cards) Fee Children 15,000 won Consult Kim Yun-ho Languages English, Chinese, Japanese Group (+82-70-4280-8821) for groups with available 20 or more persons Grévin Museum, a leading wax museum from Paris, France, opened for the first time in Asia in Seoul! ‣‣ Musée Grévin, with a 133-year history, opened in Seoul City Hall Euljiro Building after establishing itself in Montreal and Prague. ‣‣ Korea’s top location for ‘edutainment’ where various themes of the past, present, history and culture Description of Korea including K-pop and Hallyu, as well as Paris and Seoul, are presented. -

Hallym International School Program Pre-Arrival E-Brochure

Hallym International School Program Pre-departure Information 2020 Summer Flight to Korea Flight itinerary should be shared with Hallym ISSO. If you do not join the airport pick up, you can come to Hallym University by yourself: either by bus, or by train. Bus to Chuncheon Limited number of airlines use the terminal 2, but if you arrive there, move to the transportation basement 1, buy a limousine bus ticket and take the bus at the bus stop no. 10. Bus departure time: • first bus 06:30 • 40~50-minute interval • last bus 21:50 Bus to Chuncheon Most of foreign airlines arrive at the terminal 1. Buy a ticket for Chuncheon at one of the ticket offices Inside and outside the passenger terminal. Bus departure time: first bus 07:00 / 40~50-minute interval / last bus 22:20 N.B. Please have Korean cash ready to pay for the ticket (international cards may be declined) at both terminal 1 & 2. One-way Bus Fare: 24,100 KRW Chuncheon station is the last stop. Take a limousine bus at the bus stop no. 13 Train to Chuncheon (subway + ITX) ▷ Incheon Airport Map : https://www.airport.kr/ap/en/map/mapInfo.do?TERMINAL=P01 ▷ Take the Incheon Airport Railroad (공항철도) Express train : https://www.arex.or.kr/main.do ▷ Get off at Seoul Station and change the line to no.1 (dark blue line) ▷ Arrive at Yongsan Station (just two station away) ▷ Take ITX (different ticket) to Chuncheon station Transportation to/in Seoul from Incheon Airport to Seoul Station Machine to buy a transportation card : Press English on the screen One-time usable card is refundable -

BUSAN (International) Incheon Airport (Domestic) → → Gimhae Airport (Domestic)

Transportation Information For Participants BUSAN (International) Incheon Airport (Domestic) → → Gimhae Airport (Domestic) If you arrive at Incheon airport Distance : 430km Incheon Airport from your country with Time : 1hr Incheon international flight, the easiest Airport way to go to Busan is taking a direct flight (domestic) to Gimhae airport from Incheon airport. 1hr * Passengers of domestic flights should check in at counter “A” which is the domestic flight There are more than 20 flights only check-in counter. After checking in, the passenger should enter the boarding area directly heading to Gimhae airport Gimhae Airport through the domestic departure gate. from Incheon airport everyday. Passengers should be at the boarding gate 40 Click here to see the flight schedule. minutes prior to the boarding time. http://www.airport.kr/pa/en/d/1/2/1/index.jsp Fare: Approx. KRW 70,000 (Approx. USD 61). (The fare can vary depending on the time of booking.) (International) Incheon Airport → (AREX) → Gimpo Airport (Domestic) → → Gimhae Airport (Domestic) Gimpo Airport After arriving at Incheon airport, Distance : 450km you can go to Gimpo airport to Time : 1.5hr Gimpo take a direct domestic flight to Incheon Airport Airport Gimhae airport. There are 2 ways to go to Gimpo 30mins airport from Incheon airport: AREX or airport limousine There are more than 25 flights directly Incheon Airport 1hr heading to Gimhae airport from Gimpo airport everyday. Click here to see the flight schedule. Gimhae https://goo.gl/SJ1tTx AREX Airport Fare: Approx. KRW 70,000 (Approx. USD 61) (The fare can vary depending on the time of booking.) AREX (Airport Railroad Train) station is on B1 floor The ticket office for limousine buses heading to Gimpo of Incheon airport. -

Tmark Hotel Myeongdong MAP BOOK

Tmark Hotel Myeongdong MAP BOOK 2016.12.01_ver1.0 Tourtips Tmark Hotel Myeongdong Update 2016.12.01 Version 1.0 Contents Publisher Park Sung Jae Chief Editor Nam Eun Jeong PART 01 Map Book Editor Nam Eun Jeong, Yoo Mi Sun, Kim So Yeon Whole Map 5 Myeong-dong 7 Insa-dong 9 Marketing Lee Myeong Un, Park Hyeon Yong, Kim Hye Ran Samcheong-dong&Bukchon 11 Gwanghwamun&Seochon 13 Design in-charge Kim No Soo Design Editor Bang Eun Mi PART 02 Travel Information Map Design Lee Chae Ri Tmark Hotel Myeongdong 15 SM Duty Free 16 Publishing Company Tourtips Inc. 7th floor, S&S Building, 48 Ujeongguk-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul Myeong-dong·Namdaemun·Namsan Mountain 17 Insa-dong·Jongno 24 02 - 6325 - 5201 / [email protected] Samcheong-dong·Bukchon 29 Gwanghwamun·Seochon 33 Website www.tourtips.com Recommended Tour Routes 37 Must-buy items in Korea 38 The 8 Best Items to Buy at SM Duty Free 39 The copyright of this work belongs to Tourtips Inc. This cannot be re-edited, duplicated, or changed without the written consent of the company. For commercial use, please contact the aforementioned contact details. Even for non-commercial use, the company’s consent is needed for large-scale duplication and re-distribution. Map Samcheong-dong&Bukchon 04 Legend 2016.12.01 Update Seoul 01 Whole Map Line 1 1 Line 2 2 Line 3 3 Line 4 4 Line 5 Bukchon Hanok Village 5 Gyeongui•Jungang Line G Airport Railroad Line A Tongin Market Changdeokgung Palace Gyeongbokgung Palace Seochon Anguk Gyeongbokgung 3 안국역 3 경복궁역 Gwanghwamun Insa-dong Jongmyo Shrine Center Mark Hotel 5 Gwanghwamun -

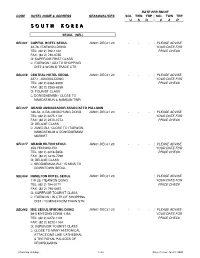

S O U T H K O R

RATE PER RM/NT CODE HOTEL NAME & ADDRESS SEASONALITIES SGL TWN TRP | SGL TWN TRP USD | CAD S O U T H K O R E A SEOUL (SEL) SEL001 CAPITAL HOTEL SEOUL JAN01-DEC31 20 - - - | PLEASE ADVISE 22-76, ITAEWON-DONG YOUR DATE FOR TEL: (82 2) 792-1122 PRICE CHECK FAX: (82 2) 792-0755 G: SUPERIOR FIRST CLASS L: ITAEWON / ADJ TO SHOPPING DIST & WORLD TRADE CTR SEL018 CENTRAL HOTEL SEOUL JAN01-DEC31 20 - - - | PLEASE ADVISE 227-1, JANGSA-DONG YOUR DATE FOR TEL: (82 2) 6365-6500 PRICE CHECK FAX: (82 2) 2265-6239 G: TOURIST CLASS L: DONGDAEMUN / CLOSE TO NAMDAEMUN & NAMSAN TWR SEL027 GRAND AMBASSADOR ASSOCIATED PULLMAN 186-54, 2-GA JANGCHUNG-DONG JAN01-DEC31 20 - - - | PLEASE ADVISE TEL: (82 2) 2275-1101 YOUR DATE FOR FAX: (82 2) 2270-0773 PRICE CHECK G: DELUXE CLASS L: JUNG-GU / CLOSE TO ITAEWON, NAMDAEMUM & DONGDAEMUM MARKET SEL017 GRAND HILTON SEOUL JAN01-DEC31 20 - - - | PLEASE ADVISE 353 YEONHUI-RO YOUR DATE FOR TEL: (82 2) 3216-5656 PRICE CHECK FAX: (82 2) 3216-7799 G: DELUXE CLASS L: SEODAEMUM-GU / 15 MINS TO DOWNTOWN SEOUL SEL004 HAMILTON HOTEL SEOUL JAN01-DEC31 20 - - - | PLEASE ADVISE 119-25, ITEAWON-DONG YOUR DATE FOR TEL: (82 2) 794-0171 PRICE CHECK FAX: (82 2) 795-0457 G: SUPERIOR TOURIST CLASS L: ITAEWON / IN CTR OF SHOPPING DIST / 10 MINS FROM TRAIN STN SEL062 IBIS SEOUL MYEONG DONG JAN01-DEC31 20 - - - | PLEASE ADVISE 59-5 MYEONG DONG 1 GA YOUR DATE FOR TEL: (82 2) 6272-1101 PRICE CHECK FAX: (82 2) 6272-1104 G: SUPERIOR TOURIST CLASS L: CLOSE TO MANY HISTORICAL ATTACTIONS LIKE CATHEDRAL & THE ROYAL PALACES OF DEOKSUGUNG Charming Holidays 1 of 3 Date of issue: Jan 21, 2020 RATE PER RM/NT CODE HOTEL NAME & ADDRESS SEASONALITIES SGL TWN TRP | SGL TWN TRP USD | CAD SEL020 KOREANA HOTEL SEOUL JAN01-DEC31 20 - - - | PLEASE ADVISE 61-1, 1-GA, TAEPYUNG-RO YOUR DATE FOR TEL: (82 2) 730-9911 PRICE CHECK FAX: (82 2) 734-0665 G: SUPERIOR FIRST CLASS L: MYEONGDONG / CLOSE TO TOKSUGUNG PALACE, GOVT.