The Central-European “Spiral Arm-Guard” Notes on the Bronze Age Asymmetrical Arm- and Anklets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

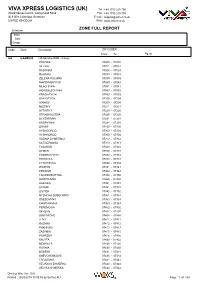

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

Skoumal Krisztián

© Skoumal Krisztián V.2021.03.13 Sorszam Kod Nev Szul.* Telepules* Apa Anya <meta name="robots" content="index,follow" /> Nr. Code Name Born* Town* Father Mother 1. RCE4000300085877092006 FABER Aloysia 1849 Temesvar Timisoara (RO) FABER Mihaly KAVASSY Anna 2. RCE4000307092773126008 FABER Anna Maria <1759 Kisjecsa Iecea Mica (RO) 3. RFK4000310085844015069 FABI Erzsebet 1844 Arad Arad (RO) FABI Janos SANTA Erzsebet 4. RFK4000310085843012035 FABI Julianna 1843 Arad Arad (RO) FABI Janos SANTA Erzsebet 5. RFK4000310085840005053 FABI Mihaly 1840Arad Arad (RO) FABI Janos SOOS Zsuzsanna 6. RFE1606003017888013002 FABIAN Antal 1863 Tiszaujlak Vylok (UA) FABIAN Karoly JASZAI Karolina 7. CREW160603201919099025 FABIAN Bela 1895 Tiszaujlak Vylok (UA) FABIAN Lajos MEZO Zsuzsanna 8. CRK3645480300899020038 FABIAN Benjamin 1899 Gergelyi Gergelyiugornya (H) FABIAN Jozsef FERENCZI Katalin 9. NRFE160612E06901013005 FABIAN Bertalan 1879 Kisdobrony Mala Dobron' (UA) FABIAN Jozsef SZALONCZI Julianna 10. NRFE160612E06929034013 FABIAN Bertalan 1902 Kisdobrony Mala Dobron' (UA) FABIAN Bertalan BODI Borbala 11. CRK3645480300898299115 FABIAN Bertalan 1898 Vasarosnameny (H) FABIAN Jozsef BODNAR Eszter 12. RFH3800090365832074004 FABIAN Borbala 1792 Nevetlenfalu Nevetlenfolu (UA) 13. RFE3800090365831044005 FABIAN Borbala <1817 Nevetlenfalu Nevetlenfolu (UA) 14. RFE1606003029936051008 FABIAN Elek 1912 Nagyszolos Vynohradiv (UA) FABIAN Bela SZEDLACSEK Maria 15. CRE3645493100942137019 FABIAN Emilia 1919 Tarpa (H) FABIAN Jozsef SZABO Erzsebet 16. NRFE160612E06916021001 FABIAN Erzsebet 1876 Kisdobrony Mala Dobron' (UA) FABIAN Jozsef SZALONTAI Julianna 17. CRE4000415500897203031 FABIAN Erzsebet 1878 Nagyszalonta Salonta (RO) FABIAN Istvan NAGY Zsuzsanna 18. RCE3800090351896001003 FABIAN Erzsebet 1880 Tiszaujlak Vylok (UA) FABIAN Jozsef GLOZER Julianna 19. RCE3800090351912019004 FABIAN Erzsebet 1892 Tiszaujlak Vylok (UA) FABIAN Jozsef GLOZER Julianna 20. CRK3645480000938065075 FABIAN Erzsebet 1938 Vasarosnameny (H) FABIAN Lajos BARATH Emma 21. RFE1606003017872002009 FABIAN Eszter 1854 Fulesd (H) 22. -

Microsoft Word

Na území Ukrajiny Берегове Berehove Затишне Zatyshne Астей Astei Бадалово Badalovo Батьово Bat'ovo Батрадь Batrad Горонглаб Horonhlab Берегуйфалу Berehuifalu Боржава Borzhava Велика Бакта Velyka Bakta Великі Береги Velyki Berehy Велика Бийгань Velyka Byihan Мала Бийгань Mala Byihan Гать Hat Геча Hecha Гут Hut Дийда Dyida Запсонь Zapson Кідьош Kid'osh Косонь Koson Гуняді Huniadi Мочола Mochola Мужієво Muzhiievo Гетен Heten Мале Попово Male Popovo Попово Popovo Рафайново Rafainovo Бадів Badiv Бакош Bakosh Данилівка Danylivka Свобода Svoboda Чома Choma Каштаново Kashtanovo Шом Shom Балажер Balazher Яноші Yanoshi Буківцьово Bukivts'ovo Великий Березний Velykyi Bereznyi Верховина-Бистра Verkhovyna-Bystra Вишка Vyshka Волосянка Volosianka Луг Luh Забрідь Zabrid Жорнава Zhornava Загорб Zahorb Кострина Kostryna Костринська Розтока Kostryns'ka Roztoka Лубня Lubnia Люта Liuta Завосина Zavosyna Малий Березний Malyi Bereznyi Мирча Myrcha Бегендяцька Пастіль Behendiats'ka Pastil Костева Пастіль Kosteva Pastil Розтоцька Пастіль Roztots'ka Pastil Руський Мочар Rus'kyi Mochar Смереково Smerekovo Домашин Domashyn Сіль Sil Ставне Stavne Княгиня Kniahynia Стричава Strychava Стужиця Stuzhytsia Гусний Husnyi Сухий Sukhyi Тихий Tykhyi Ужок Uzhok Чорноголова Chornoholova Абранка Abranka Біласовиця Bilasovytsia Латірка Latirka Буковець Bukovets Верб'яж Verbiazh Завадка Zavadka Жденієво Zhdeniievo Збини Zbyny Задільське Zadil's'ke Нижні Ворота Nyzhni Vorota Верхня Грабівниця Verkhnia Hrabivnytsia Підполоззя Pidpolozzia Ялове Yalove Кічерний Kichernyi Перехресний -

III Th International Symposium

The III I nternational Sym posium ―INVASION OF ALIEN SPECIES IN HOLARTIC. BOROK – 3‖. Programme and Book of Abstracts. October 5th-9th 2010, Borok - My shkin, Yaroslavl District, Russia. 2010. – 157 pp. The book represents proceedings of Second I nternational Sy mposium ―I nvasion of Alien Species in Holarctic. Borok - 3‖ (5 Oct. – 9 Oct. 2010, Borok - My shkin, Yaroslavl District, Russia). The articles are divided into the four main divisions: General Problems, Plants, I nvertebrates, Vertebrates. The wide spectrum of problems related to appearance and spread of invasive plants and animals is discussed. The book may be interested for specialists expertise in many fields, such as limnologists, hy drobiologists, ecologists, botanists, zoologists, geographers, managers of dealing with nature preservation and fisheries. Editors: Yury Slynko, Yury Dgebuadze, Alexandr Krylov, Dm itriy Karabanov. Cover photos by (from the above): Yury Dgebuadze, Yury Slynko, Alexandr Krylov Lable of Sym pozium : Julia Kodukhova, Yury Slynko. Yaroslavl: Print-House Publ. Co, 2010 © The Authors, 2010 © Severtsov Institute of Ecology and E volution Russian Academy of Science, Moscow, 2010 © Papanin Institute for Biology of Inland W aters Russian Academy of Science, Borok, 2010 ISBN ____________________________________________________________________ ―INVASION OF ALIEN SPECIES IN HOLARTIC. BOROK – 3‖ 3 The III International Symposium INVASION OF ALIEN SPECIES IN HOLARTIC (BOROK – 3) October 4-5, 2010 Arrival of Symposium's participants. CONFERENCE AGENDA Day 1: October 5, 2010 Myshkin Cultural Center 09:30 – 10:30 Registration 10:30 – 11:00 Welcome speeches: Dr. Alexandr I. Kopylov – director of Papanin Institute of Biology of Inland Waters Russian Academy of Science, Russia Corresponding member of RAS Yury Yu. -

Articulata 2004 Xx(X)

ARTICULATA 2015 30: 91–104 FAUNISTIK Orthoptera fauna of the Ukrainian part of the Bereg Plain (Transcarpathia, Western Ukraine) S. Szanyi, K. Katona, I. Rácz, Z. Varga & A. Nagy Abstract The Orthoptera fauna of the Bereg Plain is only partly known. While the Hungar- ian part of the area was intensively studied, investigations in the Ukrainian part have only just started in 2010. On the basis of published data and results of our samplings between 2010 and 2014 here we present distribution data of 52 Or- thoptera species (24 Ensifera and 28 Cealifera) living in the Ukrainian part. This actual data set together with the data of the Hungarian part may serve as a basis for further biogeographical, conservation biological and faunistical studies of the whole Bereg Plain area. Zusammenfassung Die Orthopterenfauna der Bereger Ebene war bislang sehr ungleichmäßig er- forscht. Während die ungarische Seite über mehrere Jahre systematisch er- forscht wurde, haben Untersuchungen auf der ukrainischen Seite erst im Jahr 2010 begonnen. Aufgrund der schon veröffentlichten Angaben und unseren ei- genen Erfassungen zwischen 2010 und 2014 haben wir das Vorkommen von 52 Orthopterenarten (24 Ensifera und 28 Caelifera) für den ukrainischen Teil nach- gewiesen. Diese Datengrundlage bietet uns nun die Möglichkeit vergleichende faunistische, biogeographische und naturschutzbiologische Untersuchungen für beide Teile der Bereger Ebene durchzuführen. Introduction The Bereg Plain is situated at the north-eastern edge of the Hungarian Great Plain and divided by the Hungarian-Ukrainian border. This part of lowland shows a unique mosaic landscape structure due to the various land use types of the lo- cal population. -

Search List N

© Skoumal Krisztián V.2021.03.13 Sorszam Kod Nev Szul.* Telepules* Apa Anya Nr. Code Name Born* Town* Father Mother 1. ZSE3644433500880003002 N Dini 1860 KantorJanosi (H) 2. RFT380090262HU14291001 N Gezane 1949 Csetfalva Chetfalva (UA) 3. ZSE3644433300881014001 N Salamon <1865 Gebe Nyirkata (H) 4. ZSE3644433400881025002 N Salamon 1859 Verecke (H) 5. RCE3850024410779073007 N. Agnes <1765 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 6. RCE3850024410796083002 N. Agnes <1782 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 7. RCE3850024410780073005 N. Anna <1766 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 8. RCE3850024410785077012 N. Anna <1771 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 9. RCE3850024410787078009 N. Anna <1773 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 10. RCE3850024410790079013 N. Anna <1776 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 11. RCE3850024410784076012 N. Anna <1770 Martonos Martonos (SRB) 12. RFE3800090365818048004 N. Anna <1804 Nevetlenfalu Nevetlenfolu (UA) 13. CRHCD048N0113908000005 N. Anna Maria 1840Eski Chehir Eskisehir (TR) 14. RCE4000307092773126006 N. Anna Maria <1759 Kisjecsa Iecea Mica (RO) 15. RCE4000307092773126007 N. Anna Maria <1759 Kisjecsa Iecea Mica (RO) 16. ZSE4000300185897019080 N. Avraham <1881 N. Avraham convert Tzedek 17. RCE4000307092773126004 N. Barbara (Borbala) <1759 Kisjecsa Iecea Mica (RO) 18. RCE4000307092774126012 N. Barbara (Borbala) <1760 Kisjecsa Iecea Mica (RO) 19. RCE3850024410786077013 N. Borbala <1772 Ada Ada (SRB) 20. RFH3800089624855014011 N. Borbala 1825 Lucskai Major Velyki Luchky (UA) 21. RFE3800090454794005000 N. Csaba <1778 Visk Vyshkove (UA) 22. RCE4000307092773126011 N. Elisabetha (Erzsebet) <1759 Kisjecsa Iecea Mica (RO) 23. RCE3850024410782075011 N. Erzsebet <1768 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 24. RCE3850024410782075013 N. Erzsebet <1768 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 25. RCE3850024410784076011 N. Erzsebet <1770 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 26. RCE3850024410784076013 N. Erzsebet <1770 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 27. RCE3850024410786077016 N. Erzsebet <1772 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 28. RCE3850024410790079011 N. Erzsebet <1776 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 29. RCE3850024410790079015 N. Erzsebet <1776 Horgos Horgos (SRB) 30. -

Integrated Report Flood Issues and Climate Changes

Flood issues and climate changes Integrated Report for Tisza River Basin Deliverable 5.1.2 May, 2018 Flood issues and climate changes - Integrated Report for Tisza River Basin Acknowledgements Lead author Daniela Rădulescu, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Sorin Rindașu, National Administration Romanian Water, Romania Daniel Kindernay, Slovak Water Management Interprise, state enterprise, Slovakia László Balatonyi dr., General Directorate of Water Management, Hungary Marina Babić Mladenović, The Jaroslav Černi Institute for the Development of Water Resources, Serbia Ratko Bajčetić, Public Water Management Company “Vode Vojvodine”, Serbia Contributing authors Andreea Cristina Gălie, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Ramona Dumitrache, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Bogdan Mirel Ion, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Ionela Florescu, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Elena Godeanu, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Elena Daniela Ghiță, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Daniela Sârbu, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Silvia Năstase, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Diana Achim, National Institute of Hydrology and Water Management, Romania Răzvan Bogzianu, National Administration Romanian Romanian Water Anca Gorduza, National Administration Romanian Romanian Water Zuzana Hiklová, Slovak -

State Geological Map of Ukraine

MINISTRY OF ECOLOGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES OF UKRAINE DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND SUBSURFACE USE SGE “ZAKHIDUKRGEOLOGIYA” STATE GEOLOGICAL MAP OF UKRAINE Scale 1:200 000 CARPATHIAN SERIES MAP SHEETS М-34-ХХIX (Snina), M-34-XXXV (Uzhgorod), L-34-V (Satu Mare) EXPLANATORY NOTES Designed by: B.V.Matskiv, B.D.Pukach, Yu.V.Kovalyov, V.M.Vorobkanych Carpathian Series map sheet Editor-in-Chief: S.S.Kruglov Editor: V.V.Kuzovenko Expert of Scientific-Editorial Council: G.D.Dosyn (Lviv Branch of UkrSGRI) English translation (2008): B.I.Malyuk Kyiv – 2001 (2008) State geological map of Ukraine. Scale 1:200 000. Carpathian Series. Map sheets М-34-ХХІX (Snina), M-34-XXXV (Uzhgorod), L-34-V (Satu Mare). Explanatory notes. – 90 pages, 3 figures, 2 annexes. Authors: B.V.Matskiv, B.D.Pukach, Yu.V.Kovalyov, V.M.Vorobkanych Carpathian Series map sheet Editor-in-Chief: S.S.Kruglov Editor: V.V.Kuzovenko Expert of Scientific-Editorial Council G.D.Dosyn (Lviv Branch of UkrSGRI) English translation (2008) B.I.Malyuk, Doctor of Geological-Mineralogical Sciences, UkrSGRI In the Explanatory notes the data on stratigraphy, magmatism, tectonics, history of geological development, geomorphology, hydrogeology, mineral resources and regularities of their distribution for the map sheets Snina, Uzhgorod and Satu Mare within Ukraine are presented. The perspectives for discovery of the ore and non-ore mineral resources, drinking, mineral and thermal waters are evaluated, brief description of ecologo- geological environment in the area is given, the list of disputable problems is provided. The lists of all discovered deposits and occurrences are presented in the annexes. -

Search List U

© Skoumal Krisztián V.2021.03.13 Sorszam Kod Nev Szul.* Telepules* Apa Anya Nr. Code Name Born* Town* Father Mother 1. CRE1606003212920579031 UCHACS Maria 1901 Kiralyhaza Korolevo (UA) UCHACS Peter HENKAN Terezia 2. ACK3646387400894213009 UCZEKAJ Endre Mihaly 1894Gonc (H) UCZEKAJ Janos BARATH Terezia 3. CRE3646387400908019008 UCZKAJ Janos 1882 Hernadpetri (H) UCZKAJ Janos OROSZ Anna 4. CRE3646387400906009009 UCZKAJ Maria 1888 Szolled Hernadvecse (H) UCZKAJ Anna 5. CRE3646387400908018005 UCZKAJ Rozalia 1889 Hernadvecse (H) UCZKAJ Istvan POLYEVKO Maria 6. CRE1606003212923618022 UDICKA Maria 1901 Kiralyhaza Korolevo (UA) UDICKA Jan CERNANCUK Anna 7. CRE1606003212917533010 UDICSKA Anna 1900 Kiralyhaza Korolevo (UA) UDICSKA Laszlo MIKULYUK Maria 8. CRE1606003212917532009 UDICSKA Laszlo 1895 Kiralyhaza Korolevo (UA) UDICSKA Janos ZSOLDOS Anna 9. CRE1606003212920571008 UDICSKA TANCZOS Maria 1901 Kiralyhaza Korolevo (UA) UDICSKA TANCZOS Janos FEHER Anna 10. CRE1606003212916528008 UDICSKA TANCZOS Marta 1896 Kiralyhaza Korolevo (UA) UDICSKA TANCZOS Janos FEHER Anna 11. CRE4000310501910016046 UDOVITS Miklos 1882 Tornya Turnu (RO) UDOVITS Istvan GRALAK Szekelia 12. RFE3800090243950027439 UDVARHELYI Arpad 1928 Kigyos Kid'osh (UA) UDVARHELYI Balazs FOJBAN Maria 13. RFE3800090243945024404 UDVARHELYI Balazs 1920 Kigyos Kid'osh (UA) UDVARHELYI Balazs PFEIKEL Maria 14. CRK1606001115900212009 UDVARHELYI Etelka 1900 Barabas (H) UDVARHELYI Imre BALOG Maria 15. CRK1606001115901481051 UDVARHELYI Ida 1901 Barabas (H) UDVARHELYI Imre BALOG Maria 16. CRK3645493700909059073 -

II. Rákóczi Ferenc Tartózkodási Helyei

Oláh Tamás II. Rákóczi Ferenc tartózkodási helyei A Rákóczi-szabadságharc 300. évfordulójának záró éve jó alkalmat kínál a korszakkal foglalkozó tudományos és honismereti munkák, dolgozatok készítésére, valamint a különböző megemlékezések tartására. Ehhez kívánunk segédletet nyújtani II. Rákóczi Ferenc (1676-1735) tartózkodási helyeinek jegyzékével, amely a kutatók és az érdeklődő nagyközönség számára is egyaránt hasznos lehet. A Nagyságos Fejedelem tartózkodási helyeit az irodalomjegyzékben szereplő művek alapján állítottuk össze. A helységeket országonként, ABC- rendben soroljuk fel. A települések neve után az érseki és püspöki városi, kamarai városi, mezővárosi és szabad királyi városi jogállást is feltüntetjük, valamint szerepel az is, ha volt a településen Rákóczi korában vár. Zárójelben találhatóak a települések névváltozatai. Itt első helyen, amennyiben voltak ilyenek, a magyar névváltozatok találhatóak, ezt követik a latin, német, román, ruszin, szerb, szlovák, horvát, stb. névalakok, illetve ahol fellelhető, a települések mai elnevezései. A történelmi Magyarország települései esetében feltüntettem, hogy mely vármegyékhez, kiváltságos kerületekhez tartoztak Rákóczi korában, illetve ma melyik magyarországi megyéhez, az elcsatolt települések esetében pedig mely országhoz tartoznak. A Magyar Királyság és az Erdélyi Fejedelemség területe mellett a jegyzék tartalmazza azokat a fontosabb európai és törökországi tartózkodási helyeket, ahol a fejedelem élete során megfordult. (Itt is megpróbáltuk a korabeli és a mai településneveket megállapítani, valamint azt, hogy ma melyik országhoz tartozik az illető település, a Lengyel-Litván Nemesi Köztársaság területén található településeknél pedig megpróbáltuk rekonstruálni, hogy az érintett település a 17-18. század folyamán melyik vajdaság területén feküdt.) Végezetül ez úton szeretnék köszönetet dr. Mészáros Kálmánnak, a HM Hadtörténeti Intézet és Múzeum Hadtörténeti Kutató Osztály munkatársának, aki rendelkezésünkre bocsátotta Esze Tamás alábbi kéziratát: II. -

Acari, Oribatida) from Ukraine

FRAGMENTA FAUNISTICA 61 (1): 55–59, 2018 PL ISSN 0015-9301 © MUSEUM AND INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY PAS DOI 10.3161/00159301FF2018.61.1.055 First records of some Oribatid mite species (Acari, Oribatida) from Ukraine Habriel H. HUSHTAN State Museum of Natural History, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Teatralna Str., 18, Lviv, 79008, Ukraine; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Four species of oribatid mites known mainly from central Europe: Oppiella hygrophila (Mahunka, 1987), Oxyoppia europaea Mahunka, 1982, Achipteria cf. quadridentata Willmann, 1951 and Ceratozetes cf. psammophilus Horak, 2000 are recorded from Ukraine for the first time. The new records of the first three species extend the known areas of their occurrence to the east of Europe (Zakarpattia region). Key words: Acariformes, Oribatida, mites, first records, Transcarpathian lowland, Ukraine INTRODUCTION The contemporary fauna of the oribarid mites of the world consists of more than 11 thousand species (1278 genera and 163 families) (Subias 2018). More than 700 species (ca. 7 % of the world fauna are known from Ukraine) (Yaroshenko 2000). But the fauna is being studied, the number of taxa is increasing (Melamud 2003, 2008, 2009, Hushtan 2015, 2017). Transcarpathia (Zakarpattia) is one of the richest in the taxonomic relation of the regions of Ukraine. No less interesting for taxonomists is the Transcarpathian lowland. The oribatid mites remained poorly studied in this territory (Hushtan 2017). While identifying the material from the samples collected in the Transcarpathian plain, four oribatid species, previously known only from neighboring Central European countries, were found. MATERIAL AND METHODS All of these studies are conducted according to generally accepted methods of soil zoology (Krantz & Walter 2009, Potapov & Kuznetsova 2011). -

Traditional Timber-Framed Construction, Case Study: the Rabbi Family House in Koromľa, Slovakia

Науковий вісник Ужгородського університету, серія «Історія», вип. 1 (44), 2021 УДК 94(437.6):728.6 DOI: 10.24144/2523-4498.1(44).2021.233152 TRADITIONAL TIMBER-FRAMED CONSTRUCTION, CASE STUDY: THE RABBI FAMILY HOUSE IN KOROMĽA, SLOVAKIA Mgr. Volovár Maroš PhD graduant at Department of Theory and History of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture, Czech Technical University in Prague, Czech Republic E-mail: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6307-622X Timber-framed structures are of particular cultural significance. Their wide global and historical occurrence is proved from the oldest prehistory era recorded by archaeological finds to its actual boom in contemporary residential architecture. From ancient times until today, the reasons for their popularity are the low financial costs and fast construction process, and, in some regions, earthquake and flood resistance. The predominance of stone or brick-walled buildings we are surrounded with is relatively recent compared with the historical prevalence of timber structures. In this paper, the traditional construction nature of settlements in the lowland and hilly countryside of the upper Tisa region basin will be illustrated by the example of already a rare residential monument preserved on the eastern edge of Slovakia, close to the current borders with Ukraine, in the former Ung County. Single-storied cellar-less house Nr. 114 in Koromľa (Sobrance District, Košice Region) has timber-framed construction with post and plank infill, a double-wide floor plan, and six rooms. In addition to the walls' technological uniqueness, the house is the last remembrance of the once considerable Jewish minority of the village and a broader region.