Leadership at the Primary School Level in Bhutan: a Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

21 Indian Nationals Among the 187 Total Covid-19 Cases in the Country

SATURDAY KUENSELTHAT THE PEOPLE SHALL BE INFORMED AUGUST 29" ( & ( & D k ' + COVID-19: Bhutan: 187 | Global: 24,605,229 | Recovered: 16,869,866 | Death: 834,771 | US: 6,046,060 ?dZ_W0)").*"+-+| West Bengal: 150,772 | Assam: 98,807 | Arunachal Pradesh: 3,633 | Sikkim: 1,542 MoE proposes to re-open classes IX to XII When lockdown ceases Yangchen C Rinzin The Ministry of Education has submitted a pro- posal to the Prime Minister to re-open Classes IX and XI along with Classes X and XII if the pandemic situation improves and the lockdown is lifted. Education Minister Jai Bir Rai told Kuensel that the proposal was readied before the na- tionwide lockdown came into force on August 11, as the ministry felt the need for face-face teaching. “But before the ministry could submit the proposal to the government, the nationwide lockdown was declared,” he said. Classes X and XII were re-opened before the From the recent mass surveillance: People queue up at Dhamdara for Covid-19 test Pg 15 lockdown in July. Regular classes for X and XII have been suspended following a nationwide lockdown on August 11. The minister said that the ministry is con- cerned, as the pandemic has affected students. We’re already noticing that closure of schools 21 Indian nationals among has impacted students and many students have also started losing interest in studies,” the minis- ter said. “We know that we’re not in a good situa- the 187 total Covid-19 tion, but we need to make a decision by keeping the virus at bay, as the trend is worrying.” Pg 2 cases in the country Younten Tshedup old man tested positive while in the the country of origin, anyone who is quarantine on August 22. -

The Executive

The Executive VOLUME I NOVEMBER 7, 2018 - NOVEMBER 7, 2019 YEAR IN OFFICE Laying foundation for change 1,000 Golden Days Plus Digital transformation Removal of “cut Teachers, the Narrowing gap Densa Meet: off” for Class X highest paid civil through pay the other servant revision Mines and Cabinet Minerals Bill AM with PM: Getting to know Revising Tourism policy 9 better Tariff revision Private sector Policies development approved committee Laying foundation for change “Climb higher on the shoulders of past achievements - your task is not to fill old shoes or follow a well-trodden path, but to forge a new road leading towards a brighter future.” His Majesty The King Royal Institute of Management August 9, 2019 Contents • Introduction 8 • From the Prime Minister 10 • Initiating change 13 • Country before party 14 • Revisiting our vision 15 • The 12th Plan is critical 18 • The Nine Thrusts 19 • Densa, the other Cabinet 22 • High value, low volume tourism 22 • More focus on health and education 24 • AM with PM: A dialogue with the Prime Minister 25 • Investing in our children 26 • Pay revised to close gap 27 • Rewarding the backbone of education 28 • Taking APA beyond formalities 29 • Block grant empowers LG 30 • Major tax reforms 30 • TVET transforms 31 • Cautious steps in hydro 32 • Encouraging responsible journalism 32 • Private sector-led economy 33 • Meeting pledges 34 • Policies Approved 36 • Guidelines reviewed and adopted 37 • Overhauling health 38 • A fair chance for every Bhutanese child 41 • Education comes first 42 • Grateful -

DNT Deregistered List.Xlsx

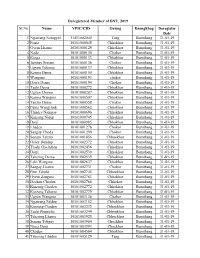

Deregistered Member of DNT, 2019 Sl.No Name VPIC/CID Gewog Dzongkhag Deregister Date 1 Ngawang Namgyel 11411002040 Tang Bumthang 31-01-19 2 Pema 10101000045 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 3 Gyem Lhamo 10101000129 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 4 Nado 10101000130 Chokor Bumthang 31-01-19 5 Kinga 10101000133 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 6 Jambay Sonam 10101000136 Chokor Bumthang 31-01-19 7 Ugyen Tshomo 10101000137 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 8 Karma Dema 10101000150 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 9 Wangmo 10101000193 chokor Bumthang 31-01-19 10 Dawa Dema 10101000194 Chokor Bumthang 31-01-19 11 Tashi Dema 10101000272 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 12 Ugyen Lhamo 10101000287 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 13 Karma Wangmo 10101000507 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 14 Tenzin Dema 10101000558 Chokor Bumthang 31-01-19 15 Pema Wangchuk 10101000562 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 16 Thinley Namgay 10101000696 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 17 Kinzang Nidup 10101000745 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 18 Dorji 10101000985 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 19 Lhaden 10101001276 Chokor Bumthang 31-01-19 20 Sangay Choda 10101001299 Chokor Bumthang 31-01-19 21 Sonam Tenzin 10101001856 Chhoekhor Bumthang 31-01-19 22 Galey Dendup 10101002372 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 23 Trashi Gyeltshen 10101002436 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 24 Dorji 10101002530 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 25 Tshering Dema 10101002539 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 26 Leki Wangmo 10101002637 Chhokhor Bumthang 31-01-19 27 Sangay Lhamo 10101002731 Chokor Bumthang 31-01-19 28 Pem Tshoki 10101002745 Chhoekhor Bumthang 31-01-19 29 Gyem Zangmo -

Report on the Status of Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT)

Report on the Status of Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT) Friday, May 16, 2014 Table of Contents BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 SUB-COMMITTEE ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 WORKING STRATEGY .............................................................................................................................................. 3 COMPARATIVE STUDY ............................................................................................................................................ 3 REPORT OF THE SUB-COMMITTEE ...................................................................................................................... 3 CRITERIA ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 OBSERVATION AND FINDINGS .............................................................................................................................. 5 ACTIVITIES AND EVENTS BY THE PARTY ............................................................................................................. 7 ISSUES FROM THE AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS AND OPERATIONS ................................................. 9 GENERAL OBSERVATION ..................................................................................................................................... -

2020-Dnt.Pdf

SL No Name CID No. Dzongkhag Date 1 Phuntsho Namgay 10102001212 Bumthang 6/30/2019 2 Dawa Gyeltshen 10204002820 Chhukha 6/30/2019 3 Buddha Maya Pradhan 11803000881 Chhukha 6/30/2019 4 Gopal Rai 10201000938 Chhukha 6/30/2019 5 Leki Tshewang 11306001267 Chhukha 6/30/2019 6 Tshewang Lhamo 10202000994 Chhukha 6/30/2019 7 Jai Bir Rai 10211004952 Chhukha 6/30/2019 8 Karma Nidup 10202000983 Chhukha 6/30/2019 9 Jurmi Wangchuk 10302002295 Dagana 6/30/2019 10 Dasho Hemant Gurung 10309001415 Dagana 6/30/2019 11 Yeshey Dem 10401000126 Gasa 6/30/2019 12 Tenzin 10403000446 Gasa 6/30/2019 13 Choki 10504000300 Haa 6/30/2019 14 Lham 10504001170 Haa 6/30/2019 15 Bidha 10504000260 Haa 6/30/2019 16 Sangay Lhadon 10503001162 Haa 6/30/2019 17 Ugen Tenzin 10502001486 Haa 6/30/2019 18 Dorji Wangmo 10504000304 Haa 6/30/2019 19 Sangay Wangmo 10601001527 Lhuentse 6/30/2019 20 Kinga Penjor 10601003230 Lhuentse 6/30/2019 21 Tumpi 10704001290 Mongar 6/30/2019 22 Tshewang 10716000347 Mongar 6/30/2019 23 Sithar Tshewang 10702001240 Mongar 6/30/2019 24 Dasho Sherab Gyeltshen 11410003114 Mongar 6/30/2019 25 Am Wangmo 10803000237 Paro 6/30/2019 26 Phub Tshering 10803000507 Paro 6/30/2019 27 Namgay Tshering 10807000770 Paro 6/30/2019 28 Ugyen Tshering 10802001958 Paro 6/30/2019 29 Phub Lham 11006000490 Punakha 6/30/2019 30 Trelkar 11001000668 Punakha 6/30/2019 31 Dasho Chagyel 11009000366 Punakha 6/30/2019 32 Nakiri 11002001272 Punakha 6/30/2019 33 Wangdi 11005001482 Punakha 6/30/2019 34 Passang Dorji 11411002872 Punakha 6/30/2019 35 Tshencho Wangdi 11008000025 Punakha 6/30/2019 -

Third Parliament of Bhutan First Session

THIRD PARLIAMENT OF BHUTAN FIRST SESSION Resolution No. 01 PROCEEDINGS AND RESOLUTION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF BHUTAN (January 2 - 24, 2019) Speaker: Wangchuk Namgyel Table of Content 1. Opening Ceremony..............................................................................1 2. Question Hour: Group A- Questions to the Prime Minister, Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs, and Ministry of Information and Communication..............................3 3. Endorsement of Committees and appointment of Committee Members......................................................................5 4. Report on the National Budget for the FY 2018-19...........................5 5. Report on the 12th Five Year Plan......................................................14 6. Question Hour: Group B- Questions to the Ministry of Works and Human Settlement, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Agriculture and Forests................................21 7. Resolutions of the Deliberation on 12th Plan Report.........................21 8. Resolutions of the Local Government Petitions.................................28 9. Question Hour: Group C: Questions to the Ministry of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Labour and Human Resources....................................................33 10. Resolutions on the Review Report by Economic and Finance Committee on the Budget of Financial Year 2018-2019........................................................................................36 11. Question Hour: Group D: Questions to the -

Isherig-2 Education ICT Master Plan 2019-2023

iSherig-2 Education ICT Master Plan 2019-2023 Education ICT Master Plan is named iSherig, which ࿉ translates to ICT in education. The “i” alludes to innovation and integration that the master plan intends to promote through use of ICT in education. iSherig logo is represented by a three-petaled ࿉ flower. Each petal represents a strategic thrust or focus area, namely iAble, iBuild and iConnect. The three jewels in the centre of the flower ࿉ represents the government’s desire to help every individual in educational institutions, government agencies in education sector and communities. iSherig is designed to impact and benefit everyone in the education sector, from children to adult learners, educators and administrators. The yellow and orange colours used in the ࿉ logo is in deference to the two colours used in our national flag, which represents peaceful coexistence of temporal authority and spiritual tradition in the country. Ministry of Education Royal Government of Bhutan Thimphu iSherig-2 Education ICT Master Plan 2019-2023 Ministry of Education Royal Government of Bhutan Thimphu Published by the Ministry of Education Kawajangsa, Thimphu 11001, Bhutan © 2019 Ministry of Education ISBN 978-99980-41-00-4 Technical Advisors Jonghwi Park, ICT in Education, UNESCO Bangkok Jian Xi Teng, ICT in Education, UNESCO Bangkok Review and Editing Pelden, NFCED, DAHE, Ministry of Education Phurba, PPD, Ministry of Education Thinley, CDC, Royal Education Council Tshering Phuntsho, TPSD, DSE, Ministry of Education Tsheyang Tshomo, ICTD, Ministry of -

DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Ii

MANIFESTO 2013 : DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA ii MANIFESTO 2013 : DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA iii NEW TIMES, NEW IDEAS. PPeople’seople’s GGovernmentovernment ...must be in the hands of the people! MANIFESTO 2013 : DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA iv Foreword by the PRESIDENT e, the Bhutanese are once more on the threshold of exercising our fundamental rights of shaping the Wdestiny of this nation, our motherland. This choice that we make will either set ablaze the ideals of democracy that we so deeply treasure. This historic hour summons DNT to rise up and answer to the call and the yearning of the Bhutanese citizens for a country that is united in peace and harmony; a government that is strong, stable and trust worthy; an economy that is progressive and sustainable; a society that prioritises happiness and bear responsibility for the elderly and the vulnerable; and a party that connects with people and bridges the gaping disparities between the rich and the downtrodden. Our kings have consolidated our sovereignty, strengthened our institutions and prepared us for the future. With democracy, all that we have witnessed in the last fi ve years was a chain of uneventful happenings: the collapse of our economy; failures and losses in opportunities; escalation in corruption and nepotism; gaping holes and disastrous fl aws in policies, of which rupee shortage and credit crunch stands as just one example. This has slackened businesses and put household plans to a standstill. Thus, 2013 beckons the Bhutanese for a greater responsibility and a fuller participation towards making a wiser choice & we must rise up and let our voices ring loud and clear to usher in change. -

Annexure 2.Xlsx

Annexure 2 Total Registered Voter Results Sl. No PARTY CANDIDATE Remarks Male Female Total EVM Votes Postal Votes Total Votes Bumthang Dzongkhag Chhoekhor_Tang Demkhong 1 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Dawa 1126 410 1536 2842 3209 6051 2 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Pema Gyamtsho 2178 1073 3251 TOTAL 3304 1483 4787 Chhumig_Ura Demkhong 1 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Karma Wangchuk 863 570 1433 1762 2023 3785 2 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Phuntsho Namgey 1010 405 1415 TOTAL 1873 975 2848 Chhukha Dzongkhag Bongo_Chapchha Demkhong 1 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Pempa 2501 978 3479 7036 7284 14320 2 DRUK NYAMRUPTSHOGPA Tshewang Lhamo 4493 2139 6632 TOTAL 6994 3117 10111 Phuentshogling Demkhong 1 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Jai Bir Rai 4611 975 5586 5401 5336 10737 2 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Tashi 2065 315 2380 TOTAL 6676 1290 7966 Dagana Dzongkhag Drukjeygang_Tseza Demkhong 1 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Jurmi Wangchuk 3978 2109 6087 6146 6359 12505 2 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Migma Dorji 1977 962 2939 TOTAL 5955 3071 9026 Lhamoi Dzingkha_Tashiding Demkhong 1 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Hemant Gurung 4333 1924 6257 6143 5922 12065 2 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Prem Kumar Khatiwara 1780 808 2588 TOTAL 6113 2732 8845 Gasa Dzongkhag Khamaed_Lunana Demkhong 1 DRUK PHUENSUMTSHOGPA Dhendup 313 48 361 471 570 1041 2 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Yeashey Dem 330 89 419 TOTAL 643 137 780 Khatoed_Laya Demkhong 1 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Changa Dawa 245 23 268 982 1082 2064 2 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Tenzin 499 89 588 TOTAL 744 112 856 Haa Dzongkhag Bji_Kar-tshog_Uesu Demkong 1 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Sonam Tobgay 669 219 888 1963 2210 4173 -

Risks High in Re-Opening Classes PP-VIII : Moh Minister

SATURDAY KUENSELTHAT THE PEOPLE SHALL BE INFORMED SEPTEMBER 12 COVID-19: Bhutan: 238 | Global: 28,343,841 | Recovered: 20,133,031 | Death: 914,123 | US: 6,588,181 | West Bengal: 193,175 | Assam: 135,805 | Arunachal Pradesh: 5,672 | Sikkim: 2,009 Flu vaccination for all to start from November Health ministry has spent Nu 1.1 billion for Covid-19 containment eforts so far Younten Tshedup With growing evidence suggesting that flu vac- cines could provide certain protection against Covid-19, the government will start vaccination for the public in November. Protection here primarily means reducing the strain on the health care system and hos- pital resources in the event of the second wave of the pandemic. Health Minister Dechen Wangmo during a press briefing yesterday said that the ministry has started to provide flu vaccines to the high- risk population – health workers, pregnant mothers, people with comorbidities, elderlies above the age of 65 and children below the age of two – beginning last year. Lyonpo said that the flu season in the coun- try peaks by mid-October and that is when Mass test: Swab samples from 1,343 people were collected yesterday as mass surveillance began in the the priority groups receive the vaccination. In four zones of Samdrupjongkhar thromde. The samples will be sent to Dewathang testing centre. the following two months, as the rest of the Pg 12 population also starts getting the flu, the mass vaccination would begin. The vaccines would cost the government more than Nu 120 million. So far the health ministry alone has spent about Nu 1.1 billion for Covid-19 containment Risks high in re-opening efforts. -

Dnt-Candidates-2018.Pdf

Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa Tentative Candidates Sl.No Candidate Dzongkhag Demkhong Gewog Chiwog Cid.No Qualification Past Experience 1 Dawa Chhoekhor-Tang Tang Gamling 10103000507 BA English (Hons) Broadcast Journalist/Media Consultant 2 Phuntsho Namgay Bumthang Chhumig-ura Chhumig Zungney 10102001212 Bachelor of Commerce Contractor 3 Jai Bir Rai Phuentshogling Phuentshogling Serina(Gangtey) 20211001195 Masters in Business Administration Economic & Financial Specialist 4 Tshewang Lhamo Chhukha Bongo-Chapchha Bjachhog Tshimasham 10202000994 B.Com Former Parliamentarian 5 Jurmi Wangchuk Drukjeygang-Tseza Drujeygang Thangna 10302002295 Masters in international relations (Major in human rights & Foreign Policy) Human Rights Specialist 6 Hemant Gurung Dagana Lhamoi Dzingkha-Tashiding Tshendagang Norbuzingkha 10309001415 Bachelor of Arts Former Parliamentarian 7 Yeshey Dem Khamaed-Lunana Khamaed Jabisa 10401000126 BA Language & Literature University Graduate 8 Tenzin Gasa Khatoed-Laya Laya Nyelo 10403000446 BA Geog Owners Community Worker 9 Ugen Tenzin Bji-Kar-Tshog-Uesu Eusu Tshaphel Tshilum 10502001486 Master in Public Administration(Environment in Politics) Former Parliamentarian 10 Dorjee Wangmo Haa Sombaykha Samar Nobgang 10504000304 Bachelor of Science in Computer Science ICT Officer 11 Kuenga Penjor Gangzur-Minjey Gangzur Somshing 10601003230 BA Dzo Owners Brocast Journalist 12 Tshering Phuntsho Lhuentse Maenbi-Tsaenkhar Metsho Gortshom-Tshangthromed 10607000554 Masters in Anthropology Researcher 13 Jigme Dorji Dramedtse-Ngatshang Ngatshang -

2019-Unclaimed Dividend

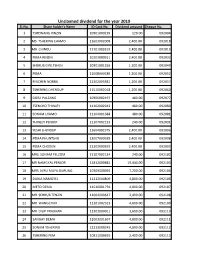

Unclaimed dividend for the year 2019 Sl.No. Share holder's Name ID Card No. Dividend amount Cheque No. 1 TSHEWANG RINZIN 10901000239 120.00 092004 2 MS TSHERING LHAMO 11603002008 2,400.00 092018 3 MR CHINDU 11101003319 2,400.00 092019 4 PEMA RINZIN 10203000921 2,400.00 092033 5 SHERUB GYELTSHEN 10901001256 1,200.00 092049 6 PEMA 11008000189 1,200.00 092052 7 RINCHEN NORBU 11302003381 1,200.00 092057 8 TSHERING DHENDUP 11510002018 1,200.00 092060 9 DORJI PALZANG 10906002497 480.00 092077 10 TSENCHO THINLEY 11102002943 480.00 092080 11 SONAM LHAMO 11104001688 480.00 092081 12 THINLEY PENJOR 11107002133 240.00 092091 13 YESHI LHENDUP 11604002375 2,400.00 092096 14 PEMA PHUNTSHO 12007000935 2,400.00 092098 15 PEMA CHODEN 21203000393 2,400.00 092099 16 MRS SONAM PELZOM 11107002134 240.00 092102 17 MR NAMGYAL PENJOR 11812000881 19,440.00 092103 18 MRS NIRU MAYA GURUNG 10309000092 7,200.00 092104 19 DAWA NAMGYEL 11212000809 4,800.00 092106 20 METO DEMA 11510001794 4,800.00 092107 21 MR SEHRUB TENZIN 11604000647 2,400.00 092108 22 MR WANGCHUK 11101002323 4,800.00 092109 23 MR DILIP PRADHAN 11203000011 3,600.00 092110 24 SANGAY DEMA 12003001697 4,800.00 092111 25 SONAM TSHERING 21213000245 4,800.00 092112 26 TSHERING PEM 10811000692 2,400.00 092113 27 WANGMITH LEPCHA 11213001380 2,400.00 092114 28 TASHI DUKPA 11214002123 2,400.00 092115 29 DAL BDR MONGER 11306002230 2,400.00 092116 30 JITEN PRADHAN 21213000555 2,400.00 092117 31 JHIMKU BISWA 11216001849 1,200.00 092118 32 RINCHEN DORJI 11510001131 1,200.00 092119 33 YONTEN 11510001689 1,200.00