John Masefield: Poet Laureate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2012

PRESS RELEASE July 2014 Poetry for the Palace Poets Laureate from Dryden to Duffy The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse 7 August – 2 November 2014 From William Wordsworth and Alfred, Lord Tennyson to Sir John Betjeman and Ted Hughes, some of Britain's most famous poets have held the position of Poet Laureate. This special honour, and appointment to the Royal Household, is awarded by the Sovereign to a poet whose work is of national significance. An exhibition opening at The Queen's Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse in August is the first ever to explore this royal tradition and the relationship between poet and monarch over 350 years. Through historic documents from the Royal Library and newly commissioned works of art, Poetry for the Palace: Poets Royal Collection Trust / Laureate from Dryden to Duffy marks the halfway point in the © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014. tenure of the current Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy. The Artwork by Stephen Raw exhibition includes original manuscripts and rare editions presented to monarchs by Poets Laureate from the 17th century to the present day, many personally inscribed, handwritten or illustrated by the poets themselves. Over three-quarters of the 52 items will go on display for the first time. Born in Scotland, Carol Ann Duffy was appointed the 20th Poet Laureate by The Queen in 2009 and is the first woman to hold the position. Her poems cover a range of subjects, from the Royal Wedding in 2011 (Rings) and the 60th anniversary of The Queen's Coronation (The Crown), to the publication of the Hillsborough Report (Liverpool) and climate change (Atlas). -

Poet's Corner in Westminster Abbey

Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey Alton Barbour Abstract: Beginning with a brief account of the history of Westminster Abbey and its physical structure, this paper concentrates on the British writers honored in the South Transept or Poet’s Corner section. It identifies those recognized who are no longer thought to be outstanding, those now understood to be outstanding who are not recognized, and provides an alphabetical listing of the honored members of dead poet’s society, Britain’s honored writers, along with the works for which they are best known. Key terms: Poet’s Corner, Westminster Abbey, South Transept. CHRISTIANITY RETURNS AND CHURCHES ARE BUILT A walk through Westminster Abbey is a walk through time and through English history from the time of the Norman conquest. Most of that journey is concerned with the crowned heads of England, but not all. One section of the Abbey has been dedicated to the major figures in British literature. This paper is concerned mainly with the major poets, novelists and dramatists of Britain, but that concentration still requires a little historical background. For over nine centuries, English monarchs have been both crowned and buried in Westminster Abbey. The Angles, Saxons and Jutes who conquered and occupied England in the mid 5th century were pagans. But, as the story goes, Pope Gregory saw two fair-haired boys in the Roman market who were being sold as slaves and asked who they were. He was told that they were Angles. He replied that they looked more like angels (angeli more than angli) and determined that these pagan people should be converted to Christianity. -

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

Download Master List

Code Title Poem Poet Read by Does Note the CD Contain AIK Conrad Aiken Reading s N The Blues of Ruby Matrix Conrad Aiken Conrad Aiken Time in the Rock (selections) Conrad Aiken Conrad Aiken A Letter from Li Po Conrad Aiken Conrad Aiken BEA(1) The Beat Generation (Vol. 1) Y San Francisco Scene (The Beat Generation) Jack Kerouac Jack Kerouac The Beat Generation (McFadden & Dor) Bob McFadden Bob McFadden Footloose in Greenwich Village Blues Montage Langston Hughes Langston Hughes / Leonard Feather Manhattan Fable Babs Gonzales Babs Gonzales Reaching Into it Ken Nordine Ken Nordine Parker's Mood King Pleasure King Pleasure Route 66 Theme Nelson Riddle Nelson Riddle Diamonds on My Windshield Tom Waits Tom Waits Naked Lunch (Excerpt) William Burroughs William Burroughs Bernie's Tune Lee Konitz Lee Konitz Like Rumpelstiltskin Don Morrow Don Morrow OOP-POP-A-DA Dizzy Gillespie Dizzy Gillespie Basic Hip (01:13) Del Close and John Del Close / John Brent Brent Christopher Columbus Digs the Jive John Drew Barrymore John Drew Barrymore The Clown (with Jean Shepherd) Charles Mingus Charles Mingus The Murder of the Two Men… Kenneth Patchen Kenneth Patchen BEA(2) The Beat Generation (Vol.2) Y The Hip Gahn (06:11) Lord Buckley Lord Buckley Twisted (02:16) Lambert, Hendricks & Lambert, Hendricks & Ross Ross Yip Roc Heresy (02:31) Slim Gaillard & His Slim Gaillard & His Middle Middle Europeans Europeans HA (02:48) Charlie Ventura & His Charlie Ventura & His Orchestra Orchestra Pull My Daisy (04:31) David Amram Quintet David Amram Quintet with with Lynn Sheffield Lynn Sheffield October in the Railroad Earth (07:08) Jack Kerouac Jack Kerouac / Steve Allen The Cool Rebellion (20:15) Howard K. -

Introduction

Notes Quotations from Love’s Martyr and the Diverse Poetical Essays are from the first edition of 1601. (I have modernized these titles in the text.) Otherwise, Shakespeare is quoted from The Riverside Shakespeare, ed. G. Blakemore Evans, 2nd edn (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997). Jonson, unless otherwise noted, is quoted from Ben Jonson, ed. C. H. Herford and Percy and Evelyn Simpson, 11 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925–52), and Edmund Spenser from The Works of Edmund Spenser: A Variorum Edition, ed. Edwin Greenlaw, Charles Osgood and Fredrick Padelford, 10 vols (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1932–57). Introduction 1. Colin Burrow, ‘Life and Work in Shakespeare’s Poems’, Shakespeare’s Poems, ed. Stephen Orgel and Sean Keilen (London: Taylor & Francis, 1999), 3. 2. J. C. Maxwell (ed.), The Cambridge Shakespeare: The Sonnets (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), xxxiii. 3. See, for instance, Catherine Belsey’s essays ‘Love as Trompe-l’oeil: Taxonomies of Desire in Venus and Adonis’, in Shakespeare in Theory and Practice (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008), 34–53, and ‘The Rape of Lucrece’, in The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Poetry, ed. Patrick Cheney (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 90–107. 4. William Empson, Essays on Shakespeare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 1. 5. I admire the efforts of recent editors to alert readers to the fact that all titles imposed on it are artificial, but there are several reasons why I reluctantly refer to it as ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’. Colin Burrow, in The Complete Sonnets and Poems (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), chooses to name it after its first line, the rather inelegant ‘Let the bird of lowdest lay’, which, out of context, to my ear sounds more silly than solemn. -

Oxford Care Homes with Nursing

2011/12 Oxfordshire – The Guide Information for older people and their carers www.oxfordshire.gov.uk/adultsocialcare Planning for Long Term Care Fees? Speak to a specialist who can guide you through the maze of red tape With prudent planning care fees do not need Please send me information about Protection & to be a problem Investment Ltd and the services it provides for Long Term Care Planning We look to provide you with: Name........................................................ A guaranteed income for life Address.................................................... The ability to live in the home of ................................................................. your choice ................................................................. No fear that your money will run out Postcode.................................................. The provision for rising care costs Tel Number.............................................. Peace of mind for you and your family Return to:Protection & Investment Ltd Gibbs House, Kennel Ride, Please call 01344 886988 or 0118 9821710 Ascot, Berkshire SL5 7NT. to speak to our specialist advisor Daniel Kasaska or visit our website www.pil.uk.com for more information. If you prefer, simply cut out and return the attached coupon. Protection and Investment Limited An independent Financial Advisor that understands the needs of elderly people. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Services Authority. Symponia member and accredited member of the Society of Later Life Advisers Advertisement 2 | Oxfordshire County Council www.oxfordshire.gov.uk Te l 0845 050 7666 [email protected] Welcome How often do you hear younger people say, “I can’t wait till I retire,” and older people say, “I’ve so much to do now, how did I ever find time to work?” Retirement brings a wealth of time to pursue a hobby, join a club or become a volunteer, see more of the grandchildren, travel, or simply relax in the garden. -

The Unanxious Influence of Spenser for Keats

The Unanxious Infl uence of Spenser for Keats Yukie Ando Synopsis The title of my essay, “The Unanxious Infl uence of Spenser for Keats” is an allusion to Harold Bloom’s The Anxiety of Infl uence, which argues that major poets inevitably swerve away from their main predecessors. I attempt to show here that the opposite is clearly true in the case of Spenser for Keats. Spenser’s infl uence continued from the beginning of his poetic carrier till the end of his life. In section 1, “Keats’s Spenser,” I present biographical details about the role of Spenser in Keats’s poetic development, focusing on the stylistic elements, the sonorities, that reared his ears. In section 2, “Spenser’s Roman à clef,” I discuss The Shepheardes Calender, a landmark in English pastoral poetry. Spenser models it primarily on Virgil’s Eclogues, but he swerves from the mel- ancholy and nostalgia that are the mainstays of traditional pastorals and deals with topical political and religious issues of the Elizabethan Age. I discuss the work in the context of the pastoral tradition and besides point out its importance for Keats and others. In section 3, “Keats’s Endymion,” I discuss this ambitious work, a pastoral poem in heroic couplets. While he was writing it, Keats took Spenser as his guiding light. Though he swerves from Spenser in thematic focus, avoiding political and religious topicality, he yet clearly imbues his lines with Spenserian sonorities, as he pursues ideal beauty. The character Endymion is himself idealized, not an ordinary shepherd, but the prince of shepherds, riding “a fair-wrought car” in pursuit of the supernal, the goddess Diana or her cynosure Cynthia. -

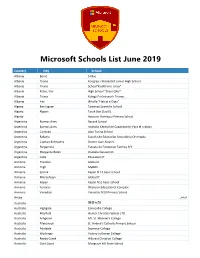

Microsoft Schools List June 2019

Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Albania Berat 5 Maj Albania Tirane Kongresi i Manastirit Junior High School Albania Tirane School"Kushtrimi i Lirise" Albania Patos, Fier High School "Zhani Ciko" Albania Tirana Kolegji Profesional i Tiranës Albania Fier Shkolla "Flatrat e Dijes" Algeria Ben Isguen Tawenza Scientific School Algeria Algiers Tarek Ben Ziad 01 Algeria Azzoune Hamlaoui Primary School Argentina Buenos Aires Bayard School Argentina Buenos Aires Instituto Central de Capacitación Para el Trabajo Argentina Cordoba Alan Turing School Argentina Rafaela Escuela de Educación Secundaria Orientada Argentina Capitan Bermudez Doctor Juan Alvarez Argentina Pergamino Escuela de Educacion Tecnica N°1 Argentina Margarita Belen Graciela Garavento Argentina Caba Educacion IT Armenia Hrazdan Global It Armenia Tegh MyBOX Armenia Syunik Kapan N 13 basic school Armenia Mikroshrjan Global IT Armenia Kapan Kapan N13 basic school Armenia Yerevan Ohanyan Educational Complex Armenia Vanadzor Vanadzor N19 Primary School الرياض Aruba Australia 坦夻易锡 Australia Highgate Concordia College Australia Mayfield Hunter Christian School LTD Australia Ashgrove Mt. St. Michael’s College Australia Ellenbrook St. Helena's Catholic Primary School Australia Adelaide Seymour College Australia Wodonga Victory Lutheran College Australia Reedy Creek Hillcrest Christian College Australia Gold Coast Musgrave Hill State School Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Australia Plainland Faith Lutheran College Australia Beaumaris Beaumaris North Primary School Australia Roxburgh Park Roxburgh Park Primary School Australia Mooloolaba Mountain Creek State High School Australia Kalamunda Kalamunda Senior High School Australia Tuggerah St. Peter's Catholic College, Tuggerah Lakes Australia Berwick Nossal High School Australia Noarlunga Downs Cardijn College Australia Ocean Grove Bellarine Secondary College Australia Carlingford Cumberland High School Australia Thornlie Thornlie Senior High School Australia Maryborough St. -

Private Schools Dominate the Rankings Again Parents

TOP 1,000 SCHOOLS FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Saturday March 8 2008 www.ft.com/top1000schools2008 Winners on a learning curve ● Private schools dominate the rankings again ● Parents' guide to the best choice ● Where learning can be a lesson for life 2 FINANCIAL TIMES SATURDAY MARCH 8 2008 Top 1,000 Schools In This Issue Location, location, education... COSTLY DILEMMA Many families are torn between spending a small fortune to live near the best state schools or paying private school fees, writes Liz Lightfoot Pages 4-5 Diploma fans say breadth is best INTERNATIONAL BACCALAUREATE Supporters of the IB believe it is better than A-levels at dividing the very brainy from the amazingly brainy, writes Francis Beckett Page 6 Hit rate is no flash in the pan GETTING IN Just 30 schools supply a quarter of successful Oxbridge applicants. Lisa Freedman looks at the variety of factors that help them achieve this Pages 8-9 Testing times: pupils at Colyton Grammar School in Devon, up from 92nd in 2006 to 85th last year, sitting exams Alamy It's not all about learning CRITERIA FOR SUCCESS In the pursuit of better academic performance, have schools lost sight of the need to produce happy pupils, asks Miranda Green Page 9 Class action The FT Top 1,000 MAIN LISTING Arranged by county, with a guide by Simon Briscoe Pages 10-15 that gets results ON THE WEB An interactive version of the top notably of all Westminster, and then regarded as highly them shows the pressure 100 schools in the ranking, and more tables, The rankings are which takes bright girls in academic said the school heads feel under. -

Edmund Spenser

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN THE PEOPLE OF WALDEN: EDMUND SPENSER “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project The People of Walden HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF WALDEN: EDMUND SPENSER PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN WALDEN: If one guest came he sometimes partook of my frugal meal, PEOPLE OF and it was no interruption to conversation to be stirring a hasty- WALDEN pudding, or watching the rising and maturing of a loaf of bread in the ashes, in the mean while. But if twenty came and sat in my house there was nothing said about dinner, though there might be bread enough for two, more than if eating were a forsaken habit; but we naturally practised abstinence; and this was never felt to be an offence against hospitality, but the most proper and considerate course. The waste and decay of physical life, which so often needs repair, seemed miraculously retarded in such a case, and the vital vigor stood its ground. I could entertain thus a thousand as well as twenty; and if any ever went away disappointed or hungry from my house when they found me at home, they may depend upon it that I sympathized with them at least. So easy is it, though many housekeepers doubt it, to establish new and better customs in place of the old. You need not rest your reputation on the dinners you give. For my own part, I was never so effectually deterred from frequenting a man’s house, by any kind of Cerberus whatever, as by the parade one made about dining me, which I took to be a very polite and roundabout hint never to trouble him so again. -

Poet Laureate

THE POETS LAUREATE OF ENGLAND “I know histhry isn’t thrue, Hinnissy, because it ain’t like what I see ivry day in Halsted Street. If any wan comes along with a histhry iv Greece or Rome that’ll show me th’ people fightin’, gettin’ dhrunk, makin’ love, gettin’ married, owin’ th’ grocery man an’ bein’ without hard coal, I’ll believe they was a Greece or Rome, but not befur.” — Dunne, Finley Peter, OBSERVATIONS BY MR. DOOLEY, New York, 1902 “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY The Poets Laureate “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX THE POETS LAUREATE OF ENGLAND 1400 Possibly as early as this year, John Gower lost his eyesight. At about this point, his CRONICA TRIPERTITA and, in English, IN PRAISE OF PEACE. Poetic praise of the new monarch King Henry IV would be rewarded with a pension paid in the form of an annual allowance of good wine from the king’s cellars.1 1. You will note that we now can denominate him as having been a “poet laureate” of England, not because he was called such in his era, for that didn’t happen, but simply because this honorable designation would eventually come to be marked by this grant of a lifetime supply of good wine from the monarch’s cellars. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE POETS LAUREATE OF ENGLAND 1591 John Wilson was born. THE SCARLET LETTER: The voice which had called her attention was that of the reverend and famous John Wilson, the eldest clergyman of Boston, a great scholar, like most of his contemporaries in the profession, and withal a man of kind and genial spirit. -

Appointment of the City of Toronto Poet Laureate (All Wards)

CITY CLERK Clause embodied in Report No. 3 of the Economic Development and Parks Committee, as adopted by the Council of the City of Toronto at its regular meeting held on April 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, and its special meeting held on April 30, May 1 and 2, 2001. 16 Appointment of the City of Toronto Poet Laureate (All Wards) (City Council at its regular meeting held on April 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, and its special meeting held on April 30, May 1 and 2, 2001, adopted this Clause, without amendment.) The Economic Development and Parks Committee recommends the adoption of the following report (March 12, 2001) from the Commissioner of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism: Purpose: The purpose of this report is to appoint the first Poet Laureate for the City of Toronto. Financial Implications and Impact Statement: Funding for the Poet Laureate honorarium is provided by a $5,000.00 allocation from funds donated to the Public Art Reserve Fund and a $5,000.00 grant from the Canada Council for the Arts. The Chief Financial Officer and Treasurer has reviewed this report and concurs with the financial impact statement. Recommendations: It is recommended that: (1) Mr. Dennis Lee be appointed the Poet Laureate for the City of Toronto for the years 2001, 2002 and 2003, under the terms outlined in this report; and (2) the appropriate City officials be authorized and directed to take the necessary action to give effect thereto. Background: At its meeting held on July 4, 5 and 6, 2000. Council directed the Commissioner of Economic Development, Culture and Tourism to develop a plan, in partnership with the League of Canadian Poets and other community stakeholders, for the selection and appointment of a Poet Laureate for the City of Toronto in 2001.