Blues and Variations for Monk for Unaccompanied French Horn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid Collection summary Prepared by Stephanie Smith, Joyce Capper, Jillian Foley, and Meaghan McCarthy 2004-2005. Creator: Diana Davies Title: The Diana Davies Photograph Collection Extent: 8 binders containing contact sheets, slides, and prints; 7 boxes (8.5”x10.75”x2.5”) of 35 mm negatives; 2 binders of 35 mm and 120 format negatives; and 1 box of 11 oversize prints. Abstract: Original photographs, negatives, and color slides taken by Diana Davies. Date span: 1963-present. Bulk dates: Newport Folk Festival, 1963-1969, 1987, 1992; Philadelphia Folk Festival, 1967-1968, 1987. Provenance The Smithsonian Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections acquired portions of the Diana Davies Photograph Collection in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Ms. Davies photographed for the Festival of American Folklife. More materials came to the Archives circa 1989 or 1990. Archivist Stephanie Smith visited her in 1998 and 2004, and brought back additional materials which Ms. Davies wanted to donate to the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives. In a letter dated 12 March 2002, Ms. Davies gave full discretion to the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage to grant permission for both internal and external use of her photographs, with the proviso that her work be credited “photo by Diana Davies.” Restrictions Permission for the duplication or publication of items in the Diana Davies Photograph Collection must be obtained from the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections. Consult the archivists for further information. Scope and Content Note The Davies photographs already held by the Rinzler Archives have been supplemented by two more recent donations (1998 and 2004) of additional photographs (contact sheets, prints, and slides) of the Newport Folk Festival, the Philadelphia Folk Festival, the Poor People's March on Washington, the Civil Rights Movement, the Georgia Sea Islands, and miscellaneous personalities of the American folk revival. -

Charles Mcpherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald

Charles McPherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald Generated on Sun, Oct 02, 2011 Date: November 20, 1964 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Carmell Jones (t), Barry Harris (p), Nelson Boyd (b), Albert 'Tootie' Heath (d) a. a-01 Hot House - 7:43 (Tadd Dameron) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! b. a-02 Nostalgia - 5:24 (Theodore 'Fats' Navarro) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! c. a-03 Passport [tune Y] - 6:55 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! d. b-01 Wail - 6:04 (Bud Powell) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! e. b-02 Embraceable You - 7:39 (George Gershwin, Ira Gershwin) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! f. b-03 Si Si - 5:50 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! g. If I Loved You - 6:17 (Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II) All titles on: Original Jazz Classics CD: OJCCD 710-2 — Bebop Revisited! (1992) Carmell Jones (t) on a-d, f-g. Passport listed as "Variations On A Blues By Bird". This is the rarer of the two Parker compositions titled "Passport". Date: August 6, 1965 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Clifford Jordan (ts), Barry Harris (p), George Tucker (b), Alan Dawson (d) a. a-01 Eronel - 7:03 (Thelonious Monk, Sadik Hakim, Sahib Shihab) b. a-02 In A Sentimental Mood - 7:57 (Duke Ellington, Manny Kurtz, Irving Mills) c. a-03 Chasin' The Bird - 7:08 (Charlie Parker) d. -

Still on the Road 1971 Recording Sessions

STILL ON THE ROAD 1971 RECORDING SESSIONS JANUARY 6 New York City, New York 1st A. J. Weberman Telephone Conversation 9 New York City, New York 2nd A. J. Weberman Telephone Conversation MARCH 16-19 New York City, New York 1st Greatest Hits recording session AUGUST 1 New York City, New York Bangla Desh Concerts SEPTEMBER 24 New York City, New York 2nd Greatest Hits recording session OCTOBER 5 New York City, New York David Bromberg recording session 30 New York City, New York Allen Ginsberg TV program 31 New York City, New York Jamming with Ginsberg and Amram NOVEMBER 4 New York City, New York George Jackson recording session 9-17, 20 New York City, New York Allen Ginsberg recording sessions Still On The Road: Bob Dylan performances and recording sessions 1971 1885 A. J. Weberman Telephone Conversation New York City, New York 6 January 1971 Notes. Telephone conversation between Bob Dylan and A. J. Weberman. Full conversation printed in The Fiddler Now Upspoke, Volume 1, Desolation Row Promotions, page 137. Unauthorized Releases (The release is unauthorized and is not associated with or approved by Bob Dylan or his current recording label) Released in the UK on THE CLASSIC INTERVIEWS VOLUME 2: THE WEBERMAN TAPES, Chrome Dreams CIS 2005, 1 August 2004. Mono telephone recording, 2 minutes. Session info updated 28 May 2012. Still On The Road: Bob Dylan performances and recording sessions 1971 1890 A. J. Weberman Telephone Conversation New York City, New York 9 January 1971 Notes Telephone conversation between Bob Dylan and A. J. Weberman . Full conversation printed in East Village Other, 19 January 1971 and reprinted in The Fiddler Now Upspoke, Volume 1, Desolation Row Promotions, page 137. -

David Amram in Denver May 10 - 13

David Amram in Denver May 10 - 13 * David Amram has composed more than 100 orchestral and chamber music works, written many scores for Broadway theater and film, including the classic scores for the films Splendor in The Grass and The Manchurian Candidate; two operas, including the ground-breaking Holocaust opera The Final Ingredient; and the score for the landmark 1959 documentary Pull My Daisy, narrated by novelist Jack Kerouac. He is also the author of two books, Vibrations, an autobiography, and Offbeat: Collaborating With Kerouac, a memoir. A pioneer player of jazz French horn, he is also a virtuoso on piano, numerous flutes and whistles, percussion, and dozens of folkloric instruments from 25 countries, as well as an inventive, funny improvisational lyricist. He has collaborated with Leonard Bernstein, who chose him as The New York Philharmonic's first composer-in-residence in 1966, Langston Hughes, Dizzy Gillespie, Dustin Hoffman, Willie Nelson, Thelonious Monk, Odetta, Elia Kazan, Arthur Miller, Charles Mingus, Lionel Hampton, E. G. Marshall, and Tito Puente. Amram's most recent work Giants of the Night is a flute concerto dedicated to the memory Charlie Parker, Jack Kerouac and Dizzy Gillespie, three American artists Amram knew and worked with. It was commissioned and recently premiered by Sir James Galway, who also plans to record it. Today, as he has for over fifty years, Amram continues to compose music while traveling the world as a conductor, soloist, bandleader, visiting scholar, and narrator in five languages. He is also currently working with author Frank McCourt on a new setting of the Mass, Missa Manhattan, as well as on a symphony commissioned by the Guthrie Foundation, Symphonic Variations on a Theme by Woody Guthrie. -

Downbeat.Com April 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. PRIL 2011 DOWNBEAT.COM A D OW N B E AT MARSALIS FAMILY // WOMEN IN JAZZ // KURT ELLING // BENNY GREEN // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2011 APRIL 2011 VOLume 78 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Maureen Flaherty ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, -

Radio Unnameable

RADIO UNNAMEABLE A Documentary Film by Paul Lovelace and Jessica Wolfson 87 minutes / 2012 / USA / English HDCAM / 16:9 / Stereo LT/RT / Color and Black & White PRESS CONTACTS: Rodrigo Brandão – [email protected] Adam Walker – [email protected] PRODUCTION CREDITS DIRECTED AND PRODUCED Paul Lovelace and Jessica Wolfson EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS P. Ellen Borowitz, MJ Glembotski, Caryl Ratner CINEMATOGRAPHY John Pirozzi EDITOR Gregory Wright ORIGINAL MUSIC Jeffrey Lewis SOUND RECORDIST Paul Lovelace SOUND DESIGN AND MIX Benny Mouthon CAS and Brian Bracken INTERVIEWS INCLUDE Margot Adler (Radio Personality) David Amram (Musician) Steve Ben Israel (Actor) Joe Boyd (Record Producer) David Bromberg (Musician) Len Chandler (Musician) Simeon Coxe (musician – Silver Apples) Judy Collins (Musician) Robert Downey Sr. (Filmmaker) Marshall Efron (Humorist) Ken Freedman (WFMU Station Manager) Bob Fass Danny Goldberg (Record Producer) Wavy Gravy (Performer/Activist) Arlo Guthrie (Musician) Larry Josephson (Radio Personality) Paul Krassner (Comedian) Kenny Kramer (Comedian) Julius Lester (Musican/Author) Judith Malina (Actor) Ed Sanders (Writer/Musician –The Fugs) Steve Post (Radio Personality) Vin Scelsa (Radio Personality) Jerry Jeff Walker (Musician) and many more… ARCHIVAL AUDIO AND VIDEO APPERANCES INCLUDE Bob Dylan Shirley Clarke Dave Van Ronk Jose Feliciano Kinky Friedman Karen Dalton Allen Ginsberg Abbie Hoffman Holly Woodlawn Herbert Hunke The Incredible String Band Carly Simon Kino Lorber Inc. • 333 West 39th Street #503 NYC 10018 • 212-629-6880 •nolorber.com [email protected] SHORT SYNOPSIS Influential radio personality Bob Fass revolutionized the airwaves by developing a patchwork of music, politics, comedy and reports from the street, effectively creating free-form radio. For nearly 50 years, Fass has been heard at midnight on listener-sponsored WBAI-FM, broadcast out of New York. -

To Download .Pdf Page 1 & 2, 8-1/2In X 11In

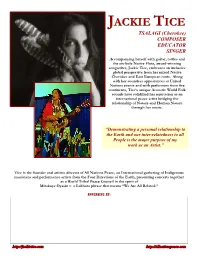

JJJAAACCCKKKIIIEEE TTTIIICCCEEE TSALAGI (Cherokee) COMPOSER EDUCATOR SINGER Accompanying herself with guitar, rattles and the six-hole Native Flute, award-winning songwriter, Jackie Tice, embraces an inclusive global perspective from her mixed Native Cherokee and East European roots. Along with her countless appearances at United Nations events and with performers from five continents, Tice’s unique Acoustic World Folk sounds have solidified her reputation as an international peace artist bridging the relationship of Nature and Human Nature through her music. "Demonstrating a personal relationship to the Earth and our inter-relatedness to all People is the major purpose of my work as an Artist.” Tice is the founder and artistic director of All Nations Peace, an International gathering of Indigenous musicians and performance artists from the Four Directions of the Earth, presenting concerts together as a World Tribal Peace Council in the spirit of Mitakuye Oyasin – a Lakhota phrase that means “We Are All Related.” APPEARING AT: http://jackietice.com http://allnationspeace.com “Hers is a voice that needs to be heard—her songs are as poetic as they are powerful!” Bill Miller, Grammy Award winner Nashville, TN USA “…truly unique….one of the most open and expressive vocal artists in the USA today. “ Greg Clayton, Spirit Horse Productions Melbourne, AUSTRALIA “I love the flute piece. Beautiful work. I’m very happy that your music will be represented in our film.” Carole Hart, Emmy award-winning director/producer New York City, NY, USA "It was an honor to have your presence [at the UN Teacher's Conference on Human Rights]. Your work is important and received very positive feedback." Dr. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

A New Annual Festival Celebrating the History and Heritage of Greenwich Village

A New Annual Festival Celebrating the History and Heritage of Greenwich Village OPENING RECEPTION IN THE VILLAGE TRIP LOUNGE An exhibition of work by celebrated music photographer David Gahr and rare Greenwich Village memorabilia from the collection of archivist Mitch Blank Music by David Amram, The Village Trip Artist-in-Residence Washington Square Hotel, Thursday September 27, at 6.30pm David Gahr (1922-2008) was destined for a career as an economics journalist but he got lost in music, opting to remain in New York City, at Sam Goody’s celebrated record store, because a staff job on New Republic would have meant moving to Washington DC, a prospect he found “a bit boring.” From his perch behind the counter, Gahr made sure to photograph the customers he recognised as musicians, quickly building up a portfolio. He turned professional in 1958 when Moses Asch, founder of Folkways Records – “that splendid, cantankerous guru of our time” - commissioned him to photograph such figures as Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston and Pete Seeger. He went on to capture now-iconic images of the great American bluesmen - Big Bill Broonzy, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and Howlin’ Wolf, musicians who were key influences on so many 1960s rock musicians. Gahr was soon the foremost photographer of the Greenwich Village jazz and folk scenes, chronicling the early years of musicians whose work would come to define the 1960s, among them Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, Odetta, Joan Baez, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Patti Smith. He photographed Bob Dylan’s celebrated 1963 Newport Folk Festival debut and captured the legendary moment in 1965 when he went electric. -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Joe Henderson: a Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-5-2016 Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2016 JOEL GEOFFREY HARRIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School JOE HENDERSON: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF HIS LIFE AND CAREER A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Joel Geoffrey Harris College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Jazz Studies December 2016 This Dissertation by: Joel Geoffrey Harris Entitled: Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Music, Program of Jazz Studies Accepted by the Doctoral Committee __________________________________________________ H. David Caffey, M.M., Research Advisor __________________________________________________ Jim White, M.M., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Socrates Garcia, D.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen Luttmann, M.L.S., M.A., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense ________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _______________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Harris, Joel. Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career. Published Doctor of Arts dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, December 2016. This study provides an overview of the life and career of Joe Henderson, who was a unique presence within the jazz musical landscape. It provides detailed biographical information, as well as discographical information and the appropriate context for Henderson’s two-hundred sixty-seven recordings.