Road Pricing in Theory and Practice: a Canadian Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology Options for the European Electronic Toll Service

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT B: STRUCTURAL AND COHESION POLICIES TRANSPORT AND TOURISM TECHNOLOGY OPTIONS FOR THE EUROPEAN ELECTRONIC TOLL SERVICE STUDY This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Transport and Tourism. AUTHORS Steer Davies Gleave - Francesco Dionori, Lucia Manzi, Roberta Frisoni Universidad Politécnica de Madrid - José Manuel Vassallo, Juan Gómez Sánchez, Leticia Orozco Rendueles José Luis Pérez Iturriaga – Senior Consultant Nick Patchett - Pillar Strategy RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR Marc Thomas Policy Department Structural and Cohesion Policies European Parliament B-1047 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE Nóra Révész LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE PUBLISHER To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe to its monthly newsletter please write to: [email protected] Manuscript completed in April 2014. © European Union, 2014. This document is available on the Internet at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/studies DISCLAIMER The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy. DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT B: STRUCTURAL AND COHESION POLICIES TRANSPORT AND TOURISM TECHNOLOGY OPTIONS FOR THE EUROPEAN ELECTRONIC TOLL SERVICE STUDY Abstract This study has been prepared to review current and future technological options for the European Electronic Toll Service. It discusses the strengths and weaknesses of each of the six technologies currently in existence. It also assesses on-going technological developments and the way forward for the European Union. -

An Intelligent Transportation Systems (Its) Plan for Canada: En Route to Intelligent Mobility

Transport Transports TP 13501 E Canada Canada AN INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS (ITS) PLAN FOR CANADA: EN ROUTE TO INTELLIGENT MOBILITY November 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................................................1 1. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................5 2. ADDRESSING TRANSPORTATION CHALLENGES.............................................5 3. WHAT ARE INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS?..............................7 4. BENEFITS OF ITS....................................................................................................9 5. AN ITS PLAN FOR CANADA - VISION AND SCOPE ..........................................12 6. MISSION: EN ROUTE TO INTELLIGENT MOBILITY .........................................14 7. OBJECTIVES .........................................................................................................14 8. PILLARS OF THE ITS PLAN.................................................................................17 9. MILESTONES.........................................................................................................27 10. CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................30 APPENDIX A ........................................................................................................... i An ITS Plan for Canada: En Route to Intelligent Mobility An ITS Plan for Canada: En Route to Intelligent -

Alternative Ways of Funding Public Transport

Alternative Ways of Funding Public Transport A Case Study Assessment Barry Ubbels1, Peter Nijkamp1, Erik Verhoef1, Steve Potter2, Marcus Enoch2 1 Department of Spatial Economics, Free University Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2 Faculty of Technology, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom EJTIR, 1, no.1 (2001), pp. 73 - 89 Received: July 2000 Accepted: August 2000 Public transport traditionally has been, and still is, heavily subsidised by local or national governments, which have been motivated by declining average cost arguments, social considerations, and the desire to offer an alternative to private car use. Conventional sources for funding, including general taxes on labour, in many occasions have become harder to sustain for various reasons. This paper explores alternative, increasingly implemented, sources of funding, i.e., local charges or taxes that are hypothecated to support (urban) public transport (such as local sales taxes, parking charges etc.). Based on an overview of several case-studies all over the world, it is found that there is a large potential for applying unconventional charging mechanisms. Not only as means of raising financial support for public transport systems, but also as a method of sending appropriate (from a sustainable point of view) pricing signals to transport use. 1. Introduction Public transport refers to a collective transport system, which is made available, usually against payment, for any person who wishes to use it. Public transportation services can be provided at various scale levels and can take different forms. Common in many cities is the public bus and to a lesser extent the tram. Fewer countries have underground services or rapid rail. -

Autopista Central, S.A. the Valuation of a Toll Road Project in Chile

The Fuqua School of Business at Duke University FUQ-04-2010 Rev. April 30, 2010 Autopista Central, S.A. The Valuation of a Toll Road Project in Chile Manuel Flores arrived to his office in Madrid on Monday after a relaxing weekend spent with his family. It was mid-November 2007 and Flores, senior vice-president of Business Development for the Spanish construction and services company ACS, had spent the last three weeks visiting ACS project sites in Latin America. Upon his return to Spain, he had had gone to a three-day infrastructure and project finance conference in Majorca where many of the most important players in the industry had been in attendance. At the conference Flores was approached by Juan Albán from the toll-road and airport operator Abertis and Sergio Sandoval from the private equity arm of Santander Bank who had an interesting proposition for him. Specifically, Albán and Sandoval expressed considerable interest in jointly buying ACS’ stake in a 61 kilometer toll-road that the firm had constructed and was now co- operating in the Chilean capital of Santiago. ACS had a 48% equity stake in this venture known in Chile as Autopista Central or “Central Highway” which had received investment of more than USD 800 million by 2007. Although some had recently begun to speculate that world asset prices had reached a peak, companies like Abertis and Santander still had appetite for infrastructure projects that they viewed as being relatively safe investments. Flores, Albán, and Sandoval had had a series of informal meetings regarding Autopista Central at the conference in which the group decided that Flores would discuss the idea of a sale of ACS’ stake with the firm’s CEO, Florentino Pérez, as soon as possible. -

Green Infrastructure Design for Transport Projects: a Road Map To

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE DESIGN FOR TRANSPORT PROJECTS A ROAD MAP TO PROTECTING ASIA’S WILDLIFE BIODIVERSITY DECEMBER 2019 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE DESIGN FOR TRANSPORT PROJECTS A ROAD MAP TO PROTECTING ASIA’S WILDLIFE BIODIVERSITY DECEMBER 2019 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2019 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 8632 4444; Fax +63 2 8636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2019. ISBN 978-92-9261-991-6 (print), 978-92-9261-992-3 (electronic) Publication Stock No. TCS189222 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS189222 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. -

Corredor Sur Trust

OFFERING MEMORANDUM US$150,000,000 CORREDOR SUR TRUST 6.95% Notes due 2025 The Issuer, BG Trust, Inc., not in its individual capacity, but solely as trustee of the Corredor Sur Trust, formed under Law 1 of 1984 of the Republic of Panama, pursuant to an irrevocable trust agreement to be entered into with ICA Panama, S.A., as settlor and secondary beneficiary, will issue the notes. The Issuer will pay interest and principal on the notes on the 25th day of each May, August, November and February of each year, commencing on August 25, 2005 in the case of interest and on August 25, 2008 in the case of principal. The notes will mature on May 25, 2025. The Issuer may, at its option, redeem some or all of the notes at any time after the third anniversary of the date of issuance of the notes at the redemption prices described in this offering memorandum. The Issuer may also redeem the notes at any time in the event of certain tax law changes requiring payment of additional amounts as described in this offering memorandum. The notes will be senior secured obligations of the Issuer and will rank equally without any preference among themselves. The notes will be secured by a first priority lien on substantially all of the assets of the Issuer. The primary beneficiary under the trust agreement will be The Bank of New York, as trustee under the indenture governing the notes. Under an assignment agreement, ICA Panama, S.A. will assign to the Issuer certain of its rights, including its rights to receive tolls generated by the Corredor Sur toll road in Panama City under a concession granted by the Panamanian government, proceeds from certain ancillary service agreements, and certain payments from the Panamanian government, in each case as more fully described herein. -

Road Transportation to the Year 2000

PRO CEE J IN S- Twenty-fourth Annual Meeting Theme: "Transportation Management, Policy and Technology" November 2-5, 1983 Marriott Crystal City Hotel Marriott Crystal Gateway Hotel Arlington, VA Volume XXIV • Number 1 1983 gc <rR TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH FORUM 1. Road Transportation Requirements To the Year 2000 by J. R. Sutherland* and M. U. Hassan** H'S PAPER presents an overview of are to avoid the experience of the state T the present and future role of the of disrepair of the U.S. highway system road mode in Canada with emphasis on due to lack of timely investment and the Provincial highway system. It brief- resulting damage to the economy, it is .d escribes the trends in road transpo- important that the state of Canada's tation demand and supply: looks at fu- road system be seriously monitored and demand and in general terms iden- appropriate measures taken. tifies the infrastructure and provincial The purpose of this paper is to pro.. flanc..ial requirements to the year 2000. scat an overview of the role of the road The keep its dominant mode in Canada with emphasis on the role private car will in passenger travel which is expect- provincial highway system. The paper ed to grow at 2% per year. The infra- briefly describes the trends in road structure will require capacity expansion transportation demand and supply: it ,en primary highways, upgrading of sur- looks at future demand and in general Laci standards on secondary highways terms identifies the infrastructure and and timely rehabilitation and mainte- financial requirements. Some alterna- ilaPe2. -

Environmental Histories of the Confederation Era Workshop, Charlottetown, PEI, 31 July – 1Aug

The Dominion of Nature: Environmental Histories of the Confederation Era workshop, Charlottetown, PEI, 31 July – 1Aug Draft essays. Do not cite or quote without permission. Wendy Cameron (Independent researcher), “Nature Ignored: Promoting Agricultural Settlement in the Ottawa Huron Tract of Canada West / Ontario” William Knight (Canada Science & Tech Museum), “Administering Fish” Andrew Smith (Liverpool), “A Bloomington School Perspective on the Dominion Fisheries Act of 1868” Brian J Payne (Bridgewater State), “The Best Fishing Station: Prince Edward Island and the Gulf of St. Lawrence Mackerel Fishery in the Era of Reciprocal Trade and Confederation Politics, 1854-1873” Dawn Hoogeveen (UBC), “Gold, Nature, and Confederation: Mining Laws in British Columbia in the wake of 1858” Darcy Ingram (Ottawa), “No Country for Animals? National Aspirations and Governance Networks in Canada’s Animal Welfare Movement” Randy Boswell (Carleton), “The ‘Sawdust Question’ and the River Doctor: Battling pollution and cholera in Canada’s new capital on the cusp of Confederation” Joshua MacFadyen (Western), “A Cold Confederation: Urban Energy Linkages in Canada” Elizabeth Anne Cavaliere (Concordia), “Viewing Canada: The cultural implications of topographic photographs in Confederation era Canada” Gabrielle Zezulka (Independent researcher), “Confederating Alberta’s Resources: Survey, Catalogue, Control” JI Little (Simon Fraser), “Picturing a National Landscape: Images of Nature in Picturesque Canada” 1 NATURE IGNORED: PROMOTING AGRICULTURAL SETTLEMENT IN -

Mfg Investment Fund Plc

MFG INVESTMENT FUND PLC (An open-ended umbrella investment company with segregated liability between sub-funds) Annual Report and Audited Financial Statements For the financial year ended 31 March 2020 Company Registration No. 525177 MFG INVESTMENT FUND PLC Annual Report and Audited Financial Statements For the financial year ended 31 March 2020 CONTENTS Page General Information 2 Background to the Company 3 Investment Manager’s Report 5 Directors’ Report 8 Depositary’s Report 11 Independent Auditor’s Report 12 Statement of Comprehensive Income 15 Statement of Financial Position 17 Statement of Changes in Net Assets Attributable to Holders of Redeemable Participating Shares 19 Statement of Cash Flows 21 Notes to the Financial Statements 23 Schedule of Investments 38 Schedule of Significant Portfolio Changes (unaudited) 48 Risk Item (unaudited) 53 UCITS Remuneration Disclosure (unaudited) 54 Appendix I - Securities Financing Transactions Regulation (unaudited) 55 Appendix II - CRS Data Protection Information Notice (unaudited) 56 1 MFG INVESTMENT FUND PLC Annual Report and Audited Financial Statements For the financial year ended 31 March 2020 GENERAL INFORMATION Directors Registered Office of the Company Bronwyn Wright* (Irish) 32 Molesworth Street Jim Cleary* (Irish) Dublin 2 Craig Wright (Australian) Ireland Investment Manager and Distributor Company Secretary MFG Asset Management MFD Secretaries Limited MLC Centre, Level 36 32 Molesworth Street 19 Martin Place Dublin 2 Sydney Ireland NSW 2000 Australia Depositary Northern Trust Fiduciary Administrator & Registrar Service (Ireland) Limited Northern Trust International Fund Administration Georges Court Services (Ireland) Limited 54-62 Townsend Street Georges Court Dublin 2 54-62 Townsend Street Ireland Dublin 2 Ireland Legal Advisers Maples and Calder Independent Auditor 75 St. -

Canada's Core Public Infrastructure Survey: Roads, Bridges and Tunnels, 2016 Released at 8:30 A.M

Canada's Core Public Infrastructure Survey: Roads, bridges and tunnels, 2016 Released at 8:30 a.m. Eastern time in The Daily, Friday, August 24, 2018 Roads Canada's road network, as reported by this survey, was long enough in 2016 to circle the Earth's equator more than 19 times. Table 1 Length of publicly-owned road assets, by type of road asset, Canada, 2016 length (kilometres) Total roads 765,917 Highways 113,135 Arterial roads 88,270 Collector roads 110,408 Local roads 440,353 Lanes and alleys 13,751 Other Sidewalks 125,238 Source(s): Table 34-10-0176-01. Statistics Canada, in partnership with Infrastructure Canada, has launched its first-ever catalogue of the state of the nation's infrastructure to provide statistical information on the stock, condition, performance and asset management strategies of Canada's core public infrastructure assets. This includes a wide variety of assets owned and operated by provincial, territorial, regional and municipal governments. These are bridges and tunnels, roads, wastewater, storm water, potable water and solid waste assets, as well as social and affordable housing, culture, recreation and sports facilities and public transit. The Daily will carry a series of releases over the coming months, each addressing a sub-group of these assets. This first release presents findings on roads, bridges and tunnels. In 2016, the country had more than 765,000 kilometres of publicly-owned roads. Road assets were classified as highways, arterial, collector and local roads, and lanes and alleys. Local roads were the most prevalent type of road asset, accounting for nearly three-fifths (57.5%) of total road length and over three-quarters of all municipally-owned roads. -

What If the Smartest Decision Was to Invest in the Planet

WHAT IF THE SMARTEST DECISION WAS TO INVEST IN THE ¿ PLANET INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 WHAT IF THE SMARTEST DECISION WAS TO INVEST IN THE ¿ PLANET INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 I Index 4 6 22 Letter At a glance The first company of a new from the Chairman sector The future is challenging 24 Business as Unusual 32 Investing in the planet 34 Experts in designing a better planet 40 INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 118 154 156 The value of doing About this report Appendices things right _ Effective, strategic, Appendix I 156 customised governance 118 Appendix II 170 Exemplary conduct under a compliance framework 138 Integrated focus on risk control and management 140 Diverse talent with expertise in designing a better planet 144 Innovation to lead the change 148 174 Leading the way to a sustainable, decarbonised Independent Assurance economy 152 Report I Letter from the Chairman Letter from the Chairman José Manuel Entrecanales CHAIRMAN OF ACCIONA ACCIONA's 2019 Integrated Report is being published in volunteers around the world who provided support and the midst of one of the most acute crises that humanity assistance where we were required. There are no borders has faced in recent history. This situation has created in this crisis, no states, no north or south. great uncertainty and severely tested the mechanisms that our society and its institutions have to resist and Situations like the one we are experiencing encourage 4 overcome adversity, however unexpected and unknown. us to persevere in our main mission as a company, focused on strengthening the basic mechanisms that My thoughts are with everyone who has lost a loved one make societies work. -

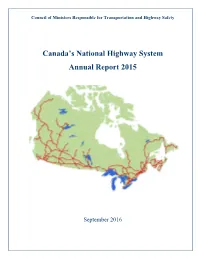

Canada's National Highway System Annual Report 2015

Council of Ministers Responsible for Transportation and Highway Safety Canada’s National Highway System Annual Report 2015 September 2016 Introduction Canada’s National Highway System is an evolution of the Trans-Canada Highway concept originally launched in 1949. Construction of the Trans-Canada Highway began in 1950 under the authority of the Trans-Canada Highway Act. In 1962 Prime Minister John Diefenbaker officially opened the Trans-Canada Highway, although construction continued until 1971. A key goal of the Trans-Canada Highway was to connect all the provinces together by highway, which was pursued through a cost-sharing partnership between federal and provincial governments to upgrade existing roadways to "Trans-Canada" standards. The Trans-Canada highway encompassed 7,821 km of highways spanning the width of the country from Victoria to St. John’s. The National Highway System (NHS) was established in 1988 by the Council of Ministers Responsible for Transportation and Highway Safety. The 24,500 kilometre network of key interprovincial and international highway linkages was identified through a federal-provincial- territorial cooperative study carried out over the period 1988 to 1992. In September 2004 the Council of Ministers approved the addition of 2,700 kilometres of new routes to the NHS, as a result of a study undertaken by Transport Canada. In September 2005, following a comprehensive review of the NHS by a federal, provincial and territorial Task Force, further expansion of the system to include an additional 11,000 kilometres of routes was endorsed by the Council of Ministers. In 2015 the National Highway System encompassed 38,076 kilometres of key highway linkages that are vital to both the economy and to the mobility of Canadians.