Transnational Organized Crime and the Palermo Convention: a Reality Check

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convention Theory: Is There a French School of Organizational Institutionalism?

CONVENTION THEORY : IS THERE A FRENCH SCHOOL OF ORGANIZATIONAL INSTITUTIONALISM? Thibault Daudigeos, Bertrand Valiorgue To cite this version: Thibault Daudigeos, Bertrand Valiorgue. CONVENTION THEORY : IS THERE A FRENCH SCHOOL OF ORGANIZATIONAL INSTITUTIONALISM?. 2010. hal-00512374 HAL Id: hal-00512374 http://hal.grenoble-em.com/hal-00512374 Preprint submitted on 30 Aug 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. "CONVENTION THEORY": IS THERE A FRENCH SCHOOL OF ORGANIZATIONAL INSTITUTIONALISM? Thibault Daudigeos Grenoble Ecole de Management Chercheur Associé, Institut Français de Gouvernement des Entreprises [email protected] Bertrand Valiorgue ESC Clermont Chercheur Associé, Institut Français de Gouvernement des Entreprises [email protected] We thank the participants of the NIW2010 and AIMS 2010 workshops for their insightful comments. 1 "CONVENTION THEORY": IS THERE A FRENCH SCHOOL OF ORGANIZATIONAL INSTITUTIONALISM? ABSTRACT This paper highlights overlap and differences between Convention Theory and New Organizational Institutionalism and thus states the strong case for profitable dialog. It shows how the former can facilitate new institutional approaches. First, convention theory rounds off the model of institutionalized action by turning the spotlight to the role of evaluation in the coordination effort. -

What Is an International Crime? (A Revisionist History)

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLI\58-2\HLI205.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-FEB-18 9:00 Volume 58, Number 2, Spring 2017 What Is an International Crime? (A Revisionist History) Kevin Jon Heller* The question “what is an international crime?” has two aspects. First, it asks us to identify which acts qualify as international crimes. Second, and more fundamentally, it asks us to identify what is distinctive about an international crime. Some disagreement exists concerning the first issue, particularly with regard to torture and terrorism. But nearly all states, international tribunals, and ICL scholars take the same position concerning the second issue, insisting that an act qualifies as an international crime if—and only if—that act is universally criminal under international law. This definition of an international crime leads to an obvious question: how exactly does an act become universally criminal under international law? One answer, the “direct criminalization thesis” (DCT), is that certain acts are universally criminal because they are directly criminalized by international law itself, regardless of whether states criminalize them. Another answer, the “national criminalization the- sis” (NCT), rejects the idea that international law directly criminalizes particular acts. According to the NCT, certain acts are universally criminal because international law obligates every state in the world to criminalize them. This Article argues that if we take positivism seriously, as every international criminal tribunal since Nuremberg has insisted we must, the NCT provides the only coherent explanation of how international law can deem certain acts to be universally criminal. I. INTRODUCTION The question posed by the title of this Article has two aspects. -

Globalization, Transnational Crime and State Power: the Need for a New Criminology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals Globalization, Transnational Crime and State Power: The Need for a New Criminology • Emilio C. Viano Riassunto Questo articolo si focalizza sulla globalizzazione legata al crimine transnazionale, mettendo in evidenza come i modelli e le dinamiche che rendono possibile ed efficace la globalizzazione portano anche a conseguenze collaterali negative, cioè criminali e facilitano l’introduzione e la rapida crescita del numero di crimini internazionali. D’altra parte, esistono anche crimini commessi contro la globalizzazione. Dal canto suo, la globalizzazione rende più facile la lotta contro il crimine grazie alla cooperazione ed al coordinamento degli sforzi in questa direzione. Di conseguenza, la globalizzazione instaura un rapporto molto complesso con il crimine: positivo, negativo e di prevenzione. Questo articolo si concentra anche su aspetti relativi a come la criminologia dovrebbe rivedere i suoi modelli di ricerca e di intervento tenendo conto del modo in cui la globalizzazione ha cambiato la maniera con la quale si può e si dovrebbe affrontare il crimine. Nell’ambito di tale articolo si ipotizza anche un mancato interesse della criminologia per i crimini della globalizzazione e si contesta la prospettiva della criminologia tradizionale che vede le definizioni legali del reato come sacrosante e immutabili. Noi abbiamo bisogno di una più ampia concettualizzazione del crimine che vada al di là delle prescrizioni del diritto penale e che utilizzi differenti tradizioni intellettuali (crimini di globalizzazione, di violenza strutturale e critica del neoliberalismo) che sottolineino l’influenza contingente del male sociale nelle scelte delle persone. -

David Lewis on Convention

David Lewis on Convention Ernie Lepore and Matthew Stone Center for Cognitive Science Rutgers University David Lewis’s landmark Convention starts its exploration of the notion of a convention with a brilliant insight: we need a distinctive social competence to solve coordination problems. Convention, for Lewis, is the canonical form that this social competence takes when it is grounded in agents’ knowledge and experience of one another’s self-consciously flexible behavior. Lewis meant for his theory to describe a wide range of cultural devices we use to act together effectively; but he was particularly concerned in applying this notion to make sense of our knowledge of meaning. In this chapter, we give an overview of Lewis’s theory of convention, and explore its implications for linguistic theory, and especially for problems at the interface of the semantics and pragmatics of natural language. In §1, we discuss Lewis’s understanding of coordination problems, emphasizing how coordination allows for a uniform characterization of practical activity and of signaling in communication. In §2, we introduce Lewis’s account of convention and show how he uses it to make sense of the idea that a linguistic expression can come to be associated with its meaning by a convention. Lewis’s account has come in for a lot of criticism, and we close in §3 by addressing some of the key difficulties in thinking of meaning as conventional in Lewis’s sense. The critical literature on Lewis’s account of convention is much wider than we can fully survey in this chapter, and so we recommend for a discussion of convention as a more general phenomenon Rescorla (2011). -

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic Saša Pišot ( [email protected] ) Science and Research Centre Koper Boštjan Šimunič Science and Research Centre Koper Ambra Gentile Università degli Studi di Palermo Antonino Bianco Università degli Studi di Palermo Gianluca Lo Coco Università degli Studi di Palermo Rado Pišot Science and Research Centre Koper Patrik Dird Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Ivana Milovanović Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Research Article Keywords: Physical activity and inactivity behavior, dietary/eating habits, well-being, home connement, COVID-19 pandemic measures Posted Date: June 9th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-537321/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/18 Abstract Background: The COVID-19 pandemic situation with the lockdown of public life caused serious changes in people's everyday practices. The study evaluates the differences between Slovenia and Italy in health- related everyday practices induced by the restrictive measures during rst wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: The study examined changes through an online survey conducted in nine European countries from April 15-28, 2020. The survey included questions from a simple activity inventory questionnaire (SIMPAQ), the European Health Interview Survey, and some other questions. To compare changes between countries with low and high incidence of COVID-19 epidemic, we examine 956 valid responses from Italy (N=511; 50% males) and Slovenia (N=445; 26% males). -

Guide on Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights

Guide on Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights Freedom of thought, Conscience and religion Updated on 30 April 2021 This Guide has been prepared by the Registry and does not bind the Court. Guide on Article 9 of the Convention – Freedom of thought, conscience and religion Publishers or organisations wishing to translate and/or reproduce all or part of this report in the form of a printed or electronic publication are invited to contact [email protected] for information on the authorisation procedure. If you wish to know which translations of the Case-Law Guides are currently under way, please see Pending translations. This Guide was originally drafted in French. It is updated regularly and, most recently, on 30 April 2021. It may be subject to editorial revision. The Case-Law Guides are available for downloading at www.echr.coe.int (Case-law – Case-law analysis – Case-law guides). For publication updates please follow the Court’s Twitter account at https://twitter.com/ECHR_CEDH. © Council of Europe/European Court of Human Rights, 2021 European Court of Human Rights 2/99 Last update: 30.04.2021 Guide on Article 9 of the Convention – Freedom of thought, conscience and religion Table of contents Note to readers .............................................................................................. 5 Introduction ................................................................................................... 6 I. General principles and applicability ........................................................... 8 A. The importance of Article 9 of the Convention in a democratic society and the locus standi of religious bodies ............................................................................................................ 8 B. Convictions protected under Article 9 ........................................................................................ 8 C. The right to hold a belief and the right to manifest it .............................................................. 11 D. -

'Transnational Criminal Law'?

MFK-Mendip Job ID: 9924BK--0085-3 3 - 953 Rev: 27-11-2003 PAGE: 1 TIME: 11:20 SIZE: 61,11 Area: JNLS OP: PB ᭧ EJIL 2003 ............................................................................................. ‘Transnational Criminal Law’? Neil Boister* Abstract International criminal law is currently subdivided into international criminal law stricto sensu — the so-called core crimes — and crimes of international concern — the so-called treaty crimes. This article suggests that the latter category can be appropriately relabelled transnational criminal law to find a doctrinal match for the criminological term transnational crime. The article argues that such a relabelling is justified because of the need to focus attention on this relatively neglected system, because of concerns about the process of criminalization of transnational conduct, legitimacy in the development of the system, doctrinal weaknesses, human rights considerations, legitimacy in the control of the system, and enforcement issues. The article argues that the distinction between international criminal law and transnational criminal law is sustainable on four grounds: the direct as opposed to indirect nature of the two systems, the application of absolute universality as opposed to more limited forms of extraterritorial jurisdiction, the protection of international interests and values as opposed to more limited transnational values and interests, and the differently constituted international societies that project these penal norms. Finally, the article argues that the term transnational criminal law is apposite because it is functional and because it points to a legal order that attenuates the distinction between national and international. 1 Introduction The term ‘transnational crime’ is commonly used by criminologists, criminal justice officials and policymakers,1 but its complementary term, ‘transnational criminal law’ (TCL), is unknown to international lawyers. -

5 Year Slurry Outlook As of 2021.Xlsx

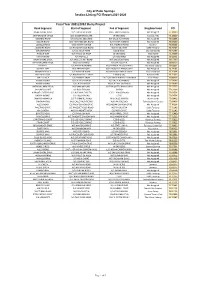

City of Palm Springs Section Listing PCI Report 2021-2026 Fiscal Year 2021/2022 Slurry Project Road Segment Start of Segment End of Segment Neighborhood PCI DINAH SHORE DRIVE W/S CROSSLEY ROAD WEST END OF BRIDGE Not Assigned 75.10000 SNAPDRAGON CIRCLE W/S GOLDENROD LANE W END (CDS) Andreas Hills 75.10000 ANDREAS ROAD E/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 75.52638 DILLON ROAD 321'' W/O MELISSA ROAD W/S KAREN AVENUE Not Assigned 75.63230 LOUELLA ROAD S/S LIVMOR AVENUE N/S ANDREAS ROAD Sunmor 75.66065 LEONARD ROAD S/S RACQUET CLUB ROAD N/S VIA OLIVERA Little Tuscany 75.70727 SONORA ROAD E/S EL CIELO ROAD E END (CDS) Los Compadres 75.71757 AMELIA WAY W/S PASEO DE ANZA W END (CDS) Vista Norte 75.78306 TIPTON ROAD N/S HWY 111 S/S RAILROAD Not Assigned 76.32931 DINAH SHORE DRIVE E/S SAN LUIS REY ROAD W/S CROSSLEY ROAD Not Assigned 76.57559 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S VISTA CHINO N/S VIA ESCUELA Not Assigned 76.60579 VIA EYTEL E/S AVENIDA PALMAS W/S AVENDA PALOS VERDES The Movie Colony 76.68892 SUNRISE WAY N/S ARENAS ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 76.74161 HERMOSA PLACE E/S MISSION ROAD W/S N PALM CANYON DRIVE Old Las Palmas 76.75654 HILLVIEW COVE E/S ANDREAS HILLS DRIVE E END (CSD) Andreas Hills 76.77835 VIA ESCUELA E/S FARRELL DRIVE 130'' E/O WHITEWATER CLUB DRIVE Gene Autry 76.80916 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 77.54599 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE ENCILIA W/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO Not Assigned 77.54599 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S RAMON ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 77.57757 DOLORES COURT LOS -

Pragmatic Reasoning and Semantic Convention: a Case Study on Gradable Adjectives*

Pragmatic Reasoning and Semantic Convention: A Case Study on Gradable Adjectives* Ming Xiang, Christopher Kennedy, Weijie Xu and Timothy Leffel University of Chicago Abstract Gradable adjectives denote properties that are relativized to contextual thresholds of application: how long an object must be in order to count as long in a context of utterance depends on what the threshold is in that context. But thresholds are variable across contexts and adjectives, and are in general uncertain. This leads to two questions about the meanings of gradable adjectives in particular contexts of utterance: what truth conditions are they understood to introduce, and what information are they taken to communicate? In this paper, we consider two kinds of answers to these questions, one from semantic theory, and one from Bayesian pragmatics, and assess them relative to human judgments about truth and communicated information. Our findings indicate that although the Bayesian accounts accurately model human judgments about what is communicated, they do not capture human judgments about truth conditions unless also supplemented with the threshold conventions postulated by semantic theory. Keywords: Gradable adjectives, Bayesian pragmatics, context dependence, semantic uncer- tainty 1 Introduction 1.1 Gradable adjectives and threshold uncertainty Gradable adjectives are predicative expressions whose semantic content is based on a scalar concept that supports orderings of the objects in their domains. For example, the gradable adjectives long and short order relative to height; heavy and light order relative to weight, and so on. Non-gradable adjectives like digital and next, on the other hand, are not associated with a scalar concept, at least not grammatically. -

Transnational Organized Crime

IPI Blue Papers Transnational Organized Crime Task Forces on Strengthening Multilateral Security Capacity No. 2 2009 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Transnational Organized Crime Transnational Organized Crime Task Forces on Strengthening Multilateral Security Capacity IPI Blue Paper No. 2 Acknowledgements The International Peace Institute (IPI) owes a great debt of gratitude to its many donors to the program Coping with Crisis, Conflict, and Change. In particular, IPI is grateful to the governments of Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The Task Forces would also not have been possible without the leadership and intellectual contribution of their co-chairs, government representatives from Permanent Missions to the United Nations in New York, and expert moderators and contributors. IPI wishes to acknowledge the support of the Greentree Foundation, which generously allowed IPI the use of the Greentree Estate for plenary meetings of the Task Forces during 2008. note Meetings were held under the Chatham House Rule. Participants were invited in their personal capacity. This report is an IPI product. Its content does not necessarily represent the positions or opinions of individual Task Force participants. © by International Peace Institute, 2009 All Rights Reserved www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Foreword, Terje Rød-Larsen. vii Acronyms. x Executive Summary. 1 The Challenge of Transnational Organized Crime (TOC). .4 Ideas for Action. .14 I. convene a hIgh-level ConFerenCe on toC aS a ThreaT To SeCurity ii. maP The impacts oF ToC on SeCurity, developmenT, and stability iii. strengThen Crime ThreaT analysis For un PeaCe efforts Iv. develoP straTegic, Investigative, and oPerational ParTnerShips v. -

Annual Report 2019

Annual Report 2019 CONNECTING POLICE FOR A SAFER WORLD Content Foreword ................................................................ 3 Database highlights.................................................................................................. 4 Countering terrorism.............................................................................................. 6 Protecting vulnerable communities................................................... 8 Securing cyberspace............................................................................................ 10 Promoting border integrity....................................................................... 12 Curbing illicit markets ....................................................................................... 14 Supporting environmental security ............................................... 16 Promoting global integrity ....................................................................... 18 Governance ..................................................................................................................... 19 Human resources .................................................................................................... 20 Finances ................................................................................................................................. 21 Looking ahead .............................................................................................................. 22 This Annual Report presents some of the highlights of our -

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Convention on the Rights of the Child Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with article 49 Preamble The States Parties to the present Convention, Considering that, in accordance with the principles proclaimed in the Charter of the United Nations, recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Bearing in mind that the peoples of the United Nations have, in the Charter, reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights and in the dignity and worth of the human person, and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Recognizing that the United Nations has, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the International Covenants on Human Rights, proclaimed and agreed that everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth therein, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, Recalling that, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations has proclaimed that childhood is entitled to special care and assistance, Convinced that the family, as the fundamental group of society and the natural environment for the growth and well-being of all its members and particularly children, should be afforded