C Arlo Sc Arp A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architectural Traces of an Admirable Cipher: Eleven in the Opus of Carlo Scarpa1

Nexus Esecutivo 19-01-2004 9:17 Seite 7 Marco Frascari Architectural Traces of an Admirable Cipher: Eleven in the Opus of Carlo Scarpa1 Consciously or unconsciously, part of the apparatus that architects use in their daily fabrications of the built environment grows out of their understanding of numbers and numerals. Marco Frascari examines the use of number and especially the number 11 in the architecture of Carlo Scarpa. In Scarpa’s opus, it is true that One and One Equals Two, but it is also wonderfully true that A Pair of Ones Makes an Eleven. Imagination is everything (Raymond Roussel 1975, p. 279). Introduction In their daily fabrications of the built environment, architects deal with the various chiastic relationships between visible and invisible. Part of the apparatus that they use, consciously or unconsciously, to imagine future constructions grows out of their understanding of numbers and numerals. To divine future buildings they rely on numeracy.2 Architectural numeracy consists in neither objective nor subjective constructs based on an arithmetical use of numbers, but rather in sedimentations of experience, formed by matter and memory. By the agency of tectonic aspects controlled by numbers, architects relate visible construction with invisible constructs. By linking recollection and anticipations, architectural numeracy deals with the meanings of constructional aspects and gives new visual angles. By using poli-dimensional tools of transversal epistemologies such as “angelic numbers” and “monstrous numerals”, the architect’s control of numbers transacts tangible matter with intangible dreams. Numbers summon up in detailed examinations what is passing and what is to come. Embodied in tectonic events and parts, numbers hinge the past and the future of buildings and their inhabitants into a search for a way of life with no impairment caused by psychic activity. -

Carlo Scarpa: Visions in Glass 1926-1962 a Private European Collection

P R E S S RELEASE | NEW YORK | 1 2 APRIL 2 0 1 7 | F O R IMMEDIATE RELEASE Carlo Scarpa: Visions in Glass 1926-1962 A Private European Collection CARLO SCARPA (1906-1978) Carlo Scarpa, circa 1970 Detail: CARLO SCARPA (1906-1978) A ‘TESSUTO-BATTUTO’ VASE, DESIGNED © Lino Bettanin - CISA A. Palladio- Regione AN IMPORTANT ‘MURRINE OPACHE’ DISH, 1938-40 Veneto CIRCA 1940 Estimate: $20,000-30,000 Estimate: $100,000-150,000 DEDICATED AUCTION | MAY 4, 2017 | CHRISTIE’S NEW YORK New York—Christie’s is pleased to announce the sale of Carlo Scarpa: Visions in Glass 1926-1962. A Private European Collection, taking place on May 4, 2017 at Christie’s New York. The sale features the only single-owner collection of works by the Venetian architect and designer Carlo Scarpa ever to be sold at auction to this day. Encompassing approximately 90 pieces of Italian art glass, the collection provides an overview of the pioneering styles Scarpa created for M.V.M. Cappellin and subsequently Venini between the years 1926 and 1962. In his collaboration with the two glassmakers and in particular with Venini, Scarpa developed a modern vocabulary for the century-old techniques of glass making and paved the way for the resurgence of the island of Murano as a center of glass with a modern outlook. Deeply influenced by his training as an architect, Scarpa developed a range of new surface treatments and techniques, while being inspired by ancient Roman glass as well as Chinese works of art. The pieces included in this collection encompass over forty years of his creations, offering a body of work which is unparalleled at auction. -

Putri Sulistyowati Sasongko 28/05/15 Modern Approach of Conserving

Modern Approach of Conserving Historic Buildings ‘Castelvecchio & Palazo Chiericati’ By Putri Sulistyowati Sasongko Kingston University London The Journey to Observe and Study the Buildings from the Trip to Italy, 23 – 27 March 2015. The study trip itinerary had provided the list of from the study trip, focusing on the observation historic buildings that are mostly designed by of conservation works on both Castelvecchio Andrea Palladio, an internationally well-known (Verona) and Palazzo Chiericati (Vicenza). Italian architect from the 16th Century. With the Even though Castelvecchio was not designed influence of Greek and Roman style by Palladio, the castle was chosen along with architecture, he also produced many of Palazzo Chiericati to be part of the case study, renaissance style buildings. Palladio is focusing on their similar approaches of the considered as one of the most influential conservation works for the building. architects in the history of European architecture. Many of his works were found in all over Italy. However, the three points of areas of study are in Vicenza, Verona, and Venice. With its historic buildings that were born earlier than United Kingdom, the Italian style architecture influenced the United Kingdom and showed the resemblance in many of the Figure 1. Castelvecchio, Restored by Carlo Scarpa in 1958 – buildings as well. Therefore, it shows that 1974 (by writer) nothing is really ‘pure’ in architecture styles, design and art- they are the group and compilations of everything that were affecting the object. This trip was considered as an architectural trail for where the students were trying to find and history and character of Italian architecture. -

Contemporary Architecture in Historic Environment: Bibliography

Bibliography Contemporary Architecture in the Historic Environment An Annotated Bibliography Edited by Sara Lardinois, Ana Paula Arato Gonçalves, Laura Matarese, and Susan Macdonald Contemporary Architecture in the Historic Environment An Annotated Bibliography Edited by Sara Lardinois, Ana Paula Arato Gonçalves, Laura Matarese, and Susan Macdonald THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES Contemporary Architecture in the Historic Environment: An Annotated Bibliography - Getty Conservation Institute - 2015 © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust The Getty Conservation Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 700 Los Angeles, CA 90049-1684 United States Telephone 310 440-7325 Fax 310 440-7702 E-mail [email protected] www.getty.edu/conservation Copy Editor: Dianne Woo ISBN: 978-1-937433-26-0 The Getty Conservation Institute works to advance conservation practice in the visual arts, broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. It serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, model field projects, and the broad dissemination of the results of both its own work and the work of others in the field. And in all its endeavors, it focuses on the creation and dissemination of knowledge that will benefit professionals and organizations responsible for the conservation of the world’s cultural heritage. Front Cover: City Hall Extension, Murcia, Spain, designed by Rafael Moneo (1991–98) Photo: © Michael Moran/OTTO Contemporary Architecture in the Historic Environment: An Annotated Bibliography -

Carlo Scarpa: Architecture and Design Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CARLO SCARPA: ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Guido Beltramini, Italo Zannier, Vaclav Sedy, Gianant Battistella | 320 pages | 13 Feb 2007 | Rizzoli International Publications | 9780847829118 | English | New York, United States Carlo Scarpa: Architecture and Design PDF Book Learn more about the change. The exhibition illustrates how Carlo Scarpa worked, with a lot of attention to the surface of the objects and the final decoration. Carlo Scarpa: Architect. The organizational Gestalt-Laws are consciously used by the master to form one wholeness of the different spogli. The art of making as well as the use and development of local traditions and crafts was of capital importance in the work of Scarpa, and it is true that the sort of crafts that he used are out of reach for the most architects and clients of today. The psychology of visual perception. A perfectionist, he would often stay throughout the night alongside the glass blowers in order to perfect new designs. Controspazio, 2. In the second line of the small Roman letters inscription, the four letters I. Carlo Scarpa a Castelvecchio: l'archivio digitale dei disegniLe fotografie sono consultabili on-line, gratuitamente e senza restrizioni, salvo l'approvazione delle condizioni di utilizzo, per gli utenti registrati. Consequently is that the reason why at these days in the architectural archives a lot of literature from others about him available is, but not literature directly from him. Tomba Brion by Carlo Scarpa. Where a flat figure has a contour as a boundary, a three-dimensional object has a surface. In conclusion the second step is essential, since the three different Gestalt-Laws are applied on this particular step. -

Frank Lloyd Wright in Venice and the Masieri Memorial

MODERNISM CONTESTED: FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT IN VENICE AND THE MASIERI MEMORIAL DEBATE by TROY MICHAEL AINSWORTH, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN LAND-USE PLANNING, MANAGEMENT, AND DESIGN Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Michael Anthony Jones Co-Chairperson of the Committee Bryce Conrad Co-Chairperson of the Committee Hendrika Buelinckx Paul Carlson Accepted John Borrelli Dean of the Graduate School May, 2005 © 2005, Troy Michael Ainsworth ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The task of writing a dissertation is realized through the work of an individual supported by many others. My journey reflects this notion. My thanks and appreciation are extended to those who participated in the realization of this project. I am grateful to Dr. Michael Anthony Jones, now retired from the College of Architecture, who directed and guided my research, offered support and suggestions, and urged me forward from the beginning. Despite his retirement, Dr. Jones’ unfaltering guidance throughout the project serves as a testament to his dedication to the advancement of knowledge. The efforts and guidance of Dr. Hendrika Buelinckx, College of Architecture, Dr. Paul Carlson, Department of History, and Dr. Bryce Conrad, Department of English, ensured the successful completion of this project, and I thank them profusely for their untiring assistance, constructive criticism, and support. I am especially grateful to James Roth of the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts, for his assistance, and I thank the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation for awarding me a research grant. Likewise, I extend my thanks to the Ernest Hemingway Foundation and Society for awarding me its Paul Smith-Michael Reynolds Founders Fellowship to enable my research. -

Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature and Architecture

PATTERNS and LAYERING Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature and Architecture Foreword by Kengo KUMA Edited by Salvator-John A. LIOTTA and Matteo BELFIORE PATTERNS and LAYERING Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature and Architecture Foreword: Kengo KUMA Editors: Salvator-John A. LIOTTA Matteo BELFIORE Graphic edition by: Ilze PakloNE Rafael A. Balboa Foreword 4 Kengo Kuma Background 6 Salvator-John A. Liotta and Matteo Belfiore Patterns, Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature, and Generative Design 8 Salvator-John A. Liotta Spatial Layering in Japan 52 Matteo Belfiore Thinking Japanese Pattern Eccentricities 98 Rafael Balboa and Ilze Paklone Evolution of Geometrical Pattern 106 Ling Zhang Development of Japanese Traditional Pattern Under the Influence of Chinese Culture 112 Yao Chen Patterns in Japanese Vernacular Architecture: Envelope Layers and Ecosystem Integration 118 Catarina Vitorino Distant Distances 126 Bojan Milan Končarević European and Japanese Space: A Different Perception Through Artists’ Eyes 134 Federico Scaroni Pervious and Phenomenal Opacity: Boundary Techniques and Intermediating Patterns as Design Strategies 140 Robert Baum Integrated Interspaces: An Urban Interpretation of the Concept of Oku 146 Cristiano Lippa Craft Mediated Designs: Explorations in Modernity and Bamboo 152 Kaon Ko Doing Patterns as Initiators of Design, Layering as Codifier of Space 160 Ko Nakamura and Mikako Koike On Pattern and Digital Fabrication 168 Yusuke Obuchi Foreword Kengo Kuma When I learned that Salvator-John A. Liotta and Matteo Belfiore in my laboratory had launched a study on patterns and layering, I had a premonition of something new and unseen in preexisting research on Japan. Conventional research on Japan has been initiated out of deep affection for Japanese architecture and thus prone to wetness and sentimentality, distanced from the universal and lacking in potential breadth of architectural theories. -

And Symbolism in Virgin with Child, Young St. John

The Biota of the Florentine Tondo: a biological survey and symbolism in Virgin with Child, Young St. John the Baptist and an Angel by Piero di Cosimo (1462-1522) A Biota do Tondo Florentino: levantamento biológico e simbolismo em Virgem com o Menino, São João Batista Criança e um Anjo de Piero di Cosimo (1462-1522) DOI: 10.20396/rhac.v1i1.13693 INÁCIO SCHILLER BITTENCOURT REBETEZ Programa de Pós-graduação em História da Arte, Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP) 0000-0002-5084-010X ALCIMAR DO LAGO CARVALHO Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) 0000-0002-5588-788X Abstract This paper describes and identifies the biological elements depicted in Virgin with Child, Young St. John the Baptist and an Angel by Piero di Cosimo (1462-1522) from the permanent collection of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, which include a bird, an insect, a mushroom and 10 vegetables, seven of which in flowering. Starting with an analysis of the probable symbolic roles of each biological element based on individual natural and biological properties then proceeding to interpret the presence of each vis-à-vis its relation to the others, this article shows the undeniable convergence of each object’s meaning: birth, death and regeneration (or reproduction) likened to the birth, death and resurrection of Christ. Keywords: Piero di Cosimo. Biological survey. Symbolism. Resumo Neste artigo, os itens biológicos representados na Virgem com o Menino, São João Batista Criança e um Anjo de Piero di Cosimo (1462-1522), do acervo do Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, incluindo um pássaro, um inseto, um cogumelo e dez vegetais, sete deles com flores, foram descritos e identificados. -

Workshop Booklet Available(Pdf)

4TH STATSEQ WORK S HOP 18TH and 19TH April, 2012 Polo Zanotto University of Verona (Italy) 3 INDEX 4TH STATSEQ WORK S HOP 18TH and 19TH April, 2012 Polo Zanotto - University of Verona (Italy) COMMITTEES & SECRETARIATS page 5 PROGRAM page 6-7 ORAL PRESENTATIONS page 9 From one for all to all for one: the NGS revolution in plant science research page 11 Assembly and temporal characterization of the V. vinifera cv. Corvina berry transcriptome page 12 TransPLANT, developing a trans-National infrastructure for Plant Genomic Science page 13 NGS data processing with Conveyor workflows page 14 MotifLab: A tools and data integration workbench for motif discovery and regulatory sequence analysis page 15 Genome-wide methods for the study of DNA-methylation inheritance page 16 A statistical approach to estimate copy number from NGS capture sequencing data page 17 Variability in RNA-seq: design and modeling page 18 A Comprehensive Evaluation of Normalization Methods for High-Throughput RNA Sequencing Data Analysis page 19 Model-based clustering for high-throughput sequencing data to determine similar expression profiles across genes page 20 Haplotype estimation and imputation using low-coverage sequence data page 21 SNP discovery from Next Generation Sequencing to study for genome variation in Arabis alpina natural populations page 22 Genotyping by sequencing tetraploid potato and attempts towards reconstruction of haplotypes page 23 Genotyping by Sequencing in Maize page 24 The effect of LD between SNPs on some statistical methods for GWAS page 25 -

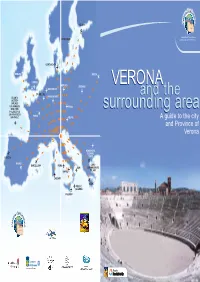

VERONA Surrounding Area VERONA Surrounding Area

Consorzio di Promozione e Commercializzazione Turistica VERONAVERONAand the surroundingsurroundingand the areaarea A guide to the city and Province of Verona TRAVEL DISTANCE BY Legend: MOTORWAY FROM VERONA TO: Trento km. 103 Fair Bolzano km. 157 Airport Vicenza km. 51 Venice km. 114 Lake Garda Brescia km. 68 Lessinia Milan km. 161 Bologna km. 142 Veronese Plain Florence km. 230 Soave Rome km. 460 Valpolicella Verona AFFI VERONA and the surrounding area A guide to the city and Province of Verona Verona Tuttintorno is proud to present the new edition of "Verona and the Surrounding Area - A Guide to the City and Province of Verona". The publication provides a general overview of the area's riches, and describes 30 fascinating itineraries to explore. The guide represents a collaborative effort between the Consortium and its members: travel agencies, hoteliers, restaurant owners, wineries, the Wine Road association, local government, transportation agencies, and tourist-sector service providers of every kind. The included itineraries offer a myriad of possibilities for enjoying the area's cultural riches, its nearby mountains, lake, and plain, getting and its world-famous enogastronomic traditions. Verona Tuttintorno, a consortium of businesses dedicated to promoting local tourism and the cultural, environmental, and enogastronomic to Verona patrimony of the City and Province of Verona, also offers up-to-date information and itinerary planning assistance for those wishing to make Verona and the surrounding area their next vacation destination. BY CAR BY TRAIN BY PLANE Enjoy Verona and the surrounding area!!! The A4 Motorway crosses the province Verona is served by the main train line The Valerio Catullo Airport, situated in of Verona from east to west. -

Bibliografia Veronese 2009 2011 Viviani Volpato UV 2014.Indd

G. F. VIVIANI ACCADEMIA DI AGRICOLTURA SCIENZE E LETTERE DI VERONA G. VOLPATO UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI VERONA BIBLIOGRAFIA VERONESE BIBLIOGRAFIA VERONESE (2009-2011) (2009-2011) di GIUSEPPE FRANCO VIVIANI e GIANCARLO VOLPATO Supplemento al vol. 185° degli Atti e Memorie dell’Accademia di Agricoltura Scienze e Lettere di Verona MMXIV VERONA · MMXIV ISBN 978-88-98513-63-5 Volumi pubblicati della “Bibliografia Veronese” Volume I: 1966-1970 (esaurito) Volume II: 1971-1973 (esaurito) Volume III: 1974-1987 (esaurito) Volume IV: 1988-1992 (esaurito) Volume V: 1993-1996 (esaurito) Volume VI: 1997-1999 (esaurito) cd: 1966-1999 (esaurito) Volume VII: 2000-2002 (esaurito) Volume VIII: 2003-2005 Volume IX: 2006-2008 Volume X: 2009-2011 ACCADEMIA DI AGRICOLTURA SCIENZE E LETTERE DI VERONA UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI VERONA BIBLIOGRAFIA VERONESE (2009-2011) di GIUSEPPE FRANCO VIVIANI e GIANCARLO VOLPATO Supplemento al vol. 185° degli Atti e Memorie dell’Accademia di Agricoltura Scienze e Lettere di Verona VERONA · MMXIV Pubblicato con il contributo del Fondo di ricerca (ex 60%) © 2014 - Dipartimento Tempo Spazio Immagine Società (TeSIS) Università degli Studi di Verona Impaginazione e stampa: Tipolitografia «La Grafica», Vago di Lavagno (Verona) ISBN 978-88-98513-63-5 INDICE Presentazione 7 Al Lettore 9 Selezione dalla critica: non per gloria né per interesse 11 Abbreviazioni 25 Avvertenza 29 Piano di classificazione 31 schede bibliografiche Generalità 41 Filosofia e discipline connesse 53 Religione 56 Scienze sociali 71 Linguistica 115 Scienze pure 120 Tecnologia (Scienze applicate) 129 Arti 135 Letteratura 206 Storia e Geografia 239 Indice degli autori 401 Indice dei soggetti 429 PRESENTAZIONE Sono trascorsi molti anni da quando i due autori della Bibliografia veronese hanno cominciato a lavorare assieme: siamo stati abituati, ormai, ad aspetta- re, a ritmi cadenzati ma sempre precisi, i loro volumi. -

Eleven in the Architecture of Carlo Scarpa

Oz Volume 13 Article 10 1-1-1991 A Deciphering of a Wonderful Cipher: Eleven in the architecture of Carlo Scarpa Marco Frascari Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/oz This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Frascari, Marco (1991) "A Deciphering of a Wonderful Cipher: Eleven in the architecture of Carlo Scarpa," Oz: Vol. 13. https://doi.org/10.4148/2378-5853.1222 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oz by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Deciphering of a Wonderful Cipher: Eleven in the architecture of Carlo Scarpa Marco Frascari The Beginning Trace: Fourth Trace: Roman people that it was necessary to but also built cosmological resonances. I am a 13. Anton Francesco Doni was an In proposing a search for an architecture protect the shield by making 11 other Traces of this tradition are still present in 18, Antonio Abbondi, called the which produces thauma-vulgarly called equal to it so whoever tried to steal the current practice. Many apothegms in the Scarpagnino, was a 14, called the 11. 1 wonder-my aim is to suggest an ap sacred object could not distinguish it architectural project. One recently re proach to the study of the theories of from the other eleven. A bronze-smith vived by formalistic trends is based on the Second Trace: architecture from a humanistic and named Mamurius Veturius was the only number three: "a perfect facade or Weak thinking is a procedure which is playful point if view.