Market Disruption Strategies: the Transformation of Xiaomi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, 8(3), 2020, 96-110 DOI: 10.15604/Ejss.2020.08.03.002

Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, 8(3), 2020, 96-110 DOI: 10.15604/ejss.2020.08.03.002 EURASIAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES www.eurasianpublications.com XIAOMI – TRANSFORMING THE COMPETITIVE SMARTPHONE MARKET TO BECOME A MAJOR PLAYER Leo Sun HELP University, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Chung Tin Fah Corresponding Author: HELP University, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Received: August 12, 2020 Accepted: September 2, 2020 Abstract Over the past six years, (between the period 2014 -2019), China's electronic information industry and mobile Internet industry has morphed rapidly in line with its economic performance. This is attributable to the strong cooperation between smart phones and the mobile Internet, capitalizing on the rapid development of mobile terminal functions. The mobile Internet is the underlying contributor to the competitive environment of the entire Chinese smartphone industry. Xiaomi began its operations with the launch of its Android-based firmware MIUI (pronounced “Me You I”) in August 2010; a modified and hardcoded user interface, incorporating features from Apple’s IOS and Samsung’s TouchWizUI. As of 2018, Xiaomi is the world’s fourth largest smartphone manufacturer, and it has expanded its products and services to include a wider range of consumer electronics and a smart home device ecosystem. It is a company focused on developing new- generation smartphone software, and Xiaomi operated a successful mobile Internet business. Xiaomi has three core products: Mi Chat, MIUI and Xiaomi smartphones. This paper will use business management models from PEST, Porter’s five forces and SWOT to analyze the internal and external environment of Xiaomi. Finally, the paper evaluates whether Xiaomi has a strategic model of sustainable development, strategic flaws and recommend some suggestions to overcome them. -

TCL 科技集团股份有限公司 TCL Technology Group Corporation

TCL Technology Group Corporation Annual Report 2019 TCL 科技集团股份有限公司 TCL Technology Group Corporation ANNUAL REPORT 2019 31 March 2020 1 TCL Technology Group Corporation Annual Report 2019 Table of Contents Part I Important Notes, Table of Contents and Definitions .................................................. 8 Part II Corporate Information and Key Financial Information ........................................... 11 Part III Business Summary .........................................................................................................17 Part IV Directors’ Report .............................................................................................................22 Part V Significant Events ............................................................................................................51 Part VI Share Changes and Shareholder Information .........................................................84 Part VII Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff .......................................93 Part VIII Corporate Governance ..............................................................................................113 Part IX Corporate Bonds .......................................................................................................... 129 Part X Financial Report............................................................................................................. 138 2 TCL Technology Group Corporation Annual Report 2019 Achieve Global Leadership by Innovation and Efficiency Chairman’s -

Dixon Technologies (India) Limited Corporate Presentation

Dixon Technologies (India) Limited Corporate Presentation October 2017 Company Overview Dixon Technologies (India) Limited Corporate Presentation 2 Dixon Overview – Largest Home Grown Design-Focused Products & Solutions Company Business overview Engaged in manufacturing of products in the consumer durables, lighting and mobile phones markets in India. Company also provide solutions in reverse logistics i.e. repair and refurbishment services of set top boxes, mobile phones and LED TV panels Fully integrated end-to-end product and solution suite to original equipment manufacturers (“OEMs”) ranging from global sourcing, manufacturing, quality testing and packaging to logistics Diversified product portfolio: LED TVs, washing machine, lighting products (LED bulbs &tubelights, downlighters and CFL bulbs) and mobile phones Leading Market position1: Leading manufacturer of FPD TVs (50.4%), washing machines (42.6%) and CFL and LED lights (38.9%) Founders: 20+ years of experience; Mr Sunil Vachani has been awarded “Man of Electronics” by CEAMA in 2015 Manufacturing Facilities: 6 state-of-the-art manufacturing units in Noida and Dehradun; accredited with quality and environmental management systems certificates Backward integration & global sourcing: In-house capabilities for panel assembly, PCB assembly, wound components, sheet metal and plastic moulding R&D capabilities: Leading original design manufacturer (“ODM”) of lighting products, LED TVs and semi-automatic washing machines Financial Snapshot: Revenue, EBITDA and PAT has grown at -

Page8national.Qxd (Page 1)

FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 2020 (PAGE 8) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU Why Indian soldiers were sent SC stays historic Puri's Rath Yatra Trump signs into law bill to punish China 'unarmed to martyrdom': Rahul NEW DELHI, June 18: due to COVID-19 pandemic over crackdown on Uyghur Muslims WASHINGTON, June 18: Muslims in Xinjiang, was International Cybersecurity Congress leader Rahul Gandhi on Thursday questioned why NEW DELHI, June 18: passed with an overwhelming Policy. Indian soldiers were sent "unarmed to martyrdom" in Ladakh The Supreme Court US President Donald Trump support from Republicans and “The internment of at least a and how dare China kill them, a day after asking the Defence Thursday stayed this year's his- has signed into law a legislation Democrats in Congress. million Uyghurs and other Minister why he did not name China in his tweet and why it toric Puri Rath Yatra starting that condemns the gross human Senator Marco Rubio Muslim minorities is reprehensi- took him two days to condole the deaths of 20 Army personnel. from June 23 as also the related rights violations of Uyghur applauded the Act and said that ble and inexcusable, and the Gandhi also shared on Twitter activities due to the COVID-19 minority groups in China’s it is an important step in coun- Chinese Communist Party and an interview of a retired Army offi- pandemic, saying that "Lord restive Muslim-majority tering the totalitarian Chinese government must be held to cer who has worked in the area Jagannath won't forgive us if we where the India-China violent Xinjiang region, paving the way government’s widespread and account. -

Type-C Compatible Device List 1.Xlsx

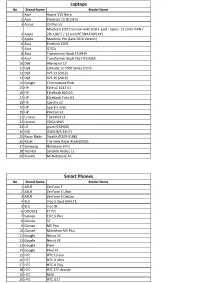

Laptops No Brand Name Model Name 1 Acer Aspire V15 Nitro 2 Acer Predator 15 (N15P3) 3 Aorus X3 Plus v5 MacBook (2015 version with USB-C port - Specs: 13.1mm THIN / 4 Apple 2lb. LIGHT / 12-inch RETINA DISPLAY) 5 Apple MacBook Pro (Late 2016 Version) 6 Asus EeeBook E202 7 Asus G752v 8 Asus Transformer Book T100HA 9 Asus Transformer Book Flip (TP200SA) 10 Dell Alienware 17 11 Dell Latitude 12 7000 Series (7275 12 Dell XPS 13 (2016) 13 Dell XPS 15 (2016) 14 Google Chromebook Pixel 15 HP Elite x2 1012 G1 16 HP EliteBook 840 G3 17 HP EliteBook Folio G1 18 HP Spectre x2 19 HP Spectre x360 20 HP Pavilion x2 21 Lenovo ThinkPad 13 22 Lenovo YOGA 900S 23 LG gram (15Z960) 24 MSI GS60 (MS-16H7) 25 Razer Blade Stealth (RZ09-0168) 26 Razer The New Razer Blade(2016) 27 Samsung Notebook 9 Pro 28 Toshiba Satellite Radius 12 29 Xiaomi Mi Notebook Air Smart Phones No Brand Name Model Name 1 ASUS ZenFone 3 2 ASUS ZenFone 3 Ultra 3 ASUS ZenFone 3 Deluxe 4 BLU Vivo 5 Dual SIM LTE 5 BLU Vivo XL 6 DOOGEE F7 Pro 7 Gionee Elife S Plus 8 Gionee S6 9 Gionee M5 Plus 10 Gionee Marathon M5 Plus 11 Google Nexus 5X 12 Google Nexus 6P 13 Google Pixel 14 Google Pixel XL 15 HTC HTC 10 evo 16 HTC HTC U Ultra 17 HTC HTC U Play 18 HTC HTC 10 Lifestyle 19 HTC M10 20 HTC HTC U11 21 Huawei Honor 22 Huawei Honor 8 23 Huawei Honor 9 24 Huawei Honor Magic 25 Huawei Hornor V9 26 Huawei Mate 9 27 Huawei Mate 9 Pro 28 Huawei Mate 9 Porsche Design 29 Huawei Nexus 6P 30 Huawei Nova2 31 Huawei P9 32 Huawei P10 33 Huawei P10 Plus 34 Huawei V8 35 Lenovo ZUK Z1(China) 36 Lenovo Zuk Z2 37 -

Compatibility Sheet

COMPATIBILITY SHEET SanDisk Ultra Dual USB Drive Transfer Files Easily from Your Smartphone or Tablet Using the SanDisk Ultra Dual USB Drive, you can easily move files from your Android™ smartphone or tablet1 to your computer, freeing up space for music, photos, or HD videos2 Please check for your phone/tablet or mobile device compatiblity below. If your device is not listed, please check with your device manufacturer for OTG compatibility. Acer Acer A3-A10 Acer EE6 Acer W510 tab Alcatel Alcatel_7049D Flash 2 Pop4S(5095K) Archos Diamond S ASUS ASUS FonePad Note 6 ASUS FonePad 7 LTE ASUS Infinity 2 ASUS MeMo Pad (ME172V) * ASUS MeMo Pad 8 ASUS MeMo Pad 10 ASUS ZenFone 2 ASUS ZenFone 3 Laser ASUS ZenFone 5 (LTE/A500KL) ASUS ZenFone 6 BlackBerry Passport Prevro Z30 Blu Vivo 5R Celkon Celkon Q455 Celkon Q500 Celkon Millenia Epic Q550 CoolPad (酷派) CoolPad 8730 * CoolPad 9190L * CoolPad Note 5 CoolPad X7 大神 * Datawind Ubislate 7Ci Dell Venue 8 Venue 10 Pro Gionee (金立) Gionee E7 * Gionee Elife S5.5 Gionee Elife S7 Gionee Elife E8 Gionee Marathon M3 Gionee S5.5 * Gionee P7 Max HTC HTC Butterfly HTC Butterfly 3 HTC Butterfly S HTC Droid DNA (6435LVW) HTC Droid (htc 6435luw) HTC Desire 10 Pro HTC Desire 500 Dual HTC Desire 601 HTC Desire 620h HTC Desire 700 Dual HTC Desire 816 HTC Desire 816W HTC Desire 828 Dual HTC Desire X * HTC J Butterfly (HTL23) HTC J Butterfly (HTV31) HTC Nexus 9 Tab HTC One (6500LVW) HTC One A9 HTC One E8 HTC One M8 HTC One M9 HTC One M9 Plus HTC One M9 (0PJA1) -

Five Forces Analysis Based on Xiaomi, a Chinese Smartphone Company Wang, Jiaying1

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 182 Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Economic Development and Business Culture (ICEDBC 2021) Five Forces Analysis Based on Xiaomi, a Chinese Smartphone Company Wang, Jiaying1 1Xi'an Teiyi High School, Xi’an, 710054, China [email protected] ABSTRACT As the development of technology and the spread of information, people’s desire and needs of smartphone increases dramatically. Admittedly, smartphone plays a crucial role in human being’s daily life as people use it as communication tools, game device, and portable office device. This paper analyzes one of the most famous smartphone brand in China -- Xiaomi to fully understand how it stands out in the industry. This analysis is mainly based upon Five Forces methodology to fully explain how Xiaomi operates and behaves in the smartphone industry. Keywords: smartphone, five forces analysis, business strategy, IoT, AIoT. 1. INTRODUCTION 2. FIVE FORCES ANALYSIS This report mainly focuses on Xiaomi, a Chinese smartphone brand and the world’s third-largest 2.1. Competitive Rivalry smartphone marker. The below report will be analyzed using the Five Forces methodology, which is a famous With the popularity of the Internet, the size of the business strategy tool to analyze a company’s smartphone industry market has been enlarged with competence in its industry. Five Forces analysis includes more brands joining the fierce competition. Customers competitive rivalry, the threat of entry, the threat of have more options when it comes to picking the right substitutes, supplier power, and buyer power. phones for themselves. Even in China, Xiaomi has to face many other competitive rivals like Huawei, OPPO, Xiaomi’s mission is to produce high-quality products and Vivo, etc, let alone the brands outside the country at affordable prices [1]. -

Statistics of Chinese SEP Cases in 2011-2019

Statistics of Chinese SEP Cases in 2011-2019 ZHAO Qishan, LU Zhe LexField Law Offices From 2011 to December 2019, Chinese courts accepted 160 cases related to SEPs. Most of the cases involve foreign entities and relate to the telecommunication industry. Most of the cases were filed with the courts in Beijing, Guangdong, Shanghai and Jiangsu. Most of the cases are patent infringement disputes, while cases asking the court to determine FRAND terms during license negotiations are also on the rise. This report includes a quantitative analysis from annual distribution, parties involved, geographic distribution of the courts, causes of action, adjudication progress and final outcomes, and also provides a particular summary of the SEP cases accepted in 2018 and 2019.1 From 2011 to 2019, Chinese courts have accepted over one hundred cases involving standard essential patents (“SEPs”) and Chinese judges have accumulated considerable judicial experience in hearing the cases. Aiming to provide a complete overview, this report analyzes information related to these SEP cases from various aspects based on the following methodology: (1) Scope of cases reviewed: The cases covered in the report are those accepted by civil courts in mainland China where the plaintiffs claimed or the defendants argued that the asserted patents were SEPs. Such cases are collectively referred to as "SEP cases" in this report. Cases that were withdrawn or dismissed due to the invalidation of asserted patents are also covered. (2) Time span: The cases included in the report are accepted by Chinese court from 2011 to December 2019. Since 2011, the number of Chinses SEP cases has gradually increased, and types of the cases have also become diversified. -

1 | Page PROJECT REPORT ON: a STUDY on MARKETING

PROJECT REPORT ON: A STUDY ON MARKETING STRATERGY OF ONE PLUS AND ITS EFFECTS ON CONSUMERS OF MUMBAI REGION SUBMITTED BY: DIVYA PUJARI T.Y. ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE (SEMESTER 6) SUBMITTED TO: PROJECT GUIDE: DR. NISHIKANT JHA ACADEMIC YEAR 2019-2020 1 | Page DECLARATION I DIVYA PUJARI FROM THAKUR COLLEGE OF SCIENCE AND COMMERCE STUDENT OF T.Y.BAF (ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE) SEM 6 HEREBY SUBMIT MY PROJECT ON “A STUDY ON MARKETING STRATEGIES OF ONE PLUS AND ITS EFFECTS ON CONSUMERS IN MUMBAI REGION” I ALSO DECLARE THAT THIS PROJECT WHICH IS PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE T.Y. BCOM (ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE) OFFERED BY UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI IS THE RESULT OF MY OWN EFFORTS WITH THE HELP OF EXPERTS DIVYA PUJARI DATE: PLACE: 2 | Page CERTIFICATE THIS IS TO CERTIFY THE PROJECT ENTITLED IS SUCCESSFULLY DONE BY DIVYA PUJARI DURING THE THIRD YEAR SIXTH SEMESTER FROM THAKUR COLLEGE OF SCIENCE AND COMMERCE KANDIVALI (EAST) MUMBAI:400101 COORDINATOR PROJECT GUIDE PRINCIPAL INTERNAL EXAMINER EXTERNAL EXAMINER 3 | Page PROJECT REPORT ON: A STUDY ON MARKETING STRATEGIES OF ONE PLUS SIMILARITY INDEX FOUND: 11.4% Date:12 February 2020 Statistics: 2591 words plagiarized/ 22734 words in total Remarks: Low plagiarism report 4 | Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To list who all have helped me is difficult because they are so numerous and the depth is so enormous. I would like to acknowledge the following as being idealistic channels and fresh dimensions in the completion of this project. I take this opportunity to thank the University of Mumbai for giving me chance to do this project. -

Innovationspolitik Im Globalen Süden

Innovationspolitik im Globalen Süden Eine vergleichende Fallstudie aufstrebender ICT-Industrien in Indien und China Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Chengzhan Zhuang aus Schanghai, VR China Bonn, 2018 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich- Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Tilman Mayer (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Xuewu GU (Guachter und Betreuer) Prof. Dr. Maximilian Mayer (Zweitgutachter) Prof. Dr. Christoph Antweiler (Weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 08.11.2017 1 Danksagung Zunächst geht mein größter Dank an Herrn Professor Xuewu Gu, der mich dazu inspiriert hat, vor Jahren nach Deutschland zu ziehen, um dort meine Promotionsforschung zu beginnen. Im Prozess der Promotion konnte ich in vielerlei Hinsicht von seiner Beratung im fachlichen wie sprachlichen profitieren. Ein besonderer Dank gilt auch Herrn Professor Maximilian Mayer. Ich kann mich noch an die Tage und Nächte erinnern, in denen wir nicht nur über den Inhalt dieser Dissertation, sondern auch über europäische Politik, China und die Beziehungen zwischen Technologie, Gesellschaft und Mensch diskutierten. Weiter danke ich Herrn Professor Tilman Mayer für die einwandfreie Organisation und Leitung des Prüfungsausschusses, der mir maßgebliche Ratschläge für die Dissertation geben konnte. Dabei bin ich auch Herrn Professor Christoph Antweiler für seine Teilnahme am Prüfungsaus- schuss dankbar. Er konnte wertvolle Fragen aufwerfen, die einen besonderen Mehrwert für meine Forschung dargestellt haben. Ein besonderer Dank geht auch an Herrn Tim Wenniges und die Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, die mich vor allem auch in den schwierigen Phasen meiner Dissertation unterstützten. Ohne sie hätte wohl die Gefahr bestanden, den Promotionsprozess aufzugeben. -

The Problem Faced and the Solution of Xiaomi Company in India

ISSN: 2278-3369 International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics Available online at: www.managementjournal.info RESEARCH ARTICLE The Problem Faced and the Solution of Xiaomi Company in India Li Kai-Sheng International Business School, Jinan University, Qianshan, Zhuhai, Guangdong, China. Abstract This paper mainly talked about the problem faced and the recommend solution of Xiaomi Company in India. The first two parts are introduction and why Xiaomi targeting at the India respectively. The third part is the three problems faced when Xiaomi operate on India, first is low brand awareness can’t attract consumes; second, lack of patent reserves and Standard Essential Patent which result in patent dispute; at last, the quality problems after-sales service problems which will influence the purchase intention and word of mouth. The fourth part analysis the cause of the problem by the SWOT analysis of Xiaomi. The fifth part is the decision criteria and alternative solutions for the problems proposed above. The last part has described the recommend solution, in short, firstly, make good use of original advantage and increase the advertising investment in spokesman and TV show; then, in long run, improve the its ability of research and development; next, increase the number of after-sales service staff and service centers, at the same, the quality of service; finally, train the local employee accept company’s culture, enhance the cross-culture management capability of managers, incentive different staff with different programs. Keywords: Cross-cultural Management, India, Mobile phone, Xiaomi. Introduction Xiaomi was founded in 2010 by serial faces different problem inevitably. -

Tamil Nadu Consumer Products Distributors Association No. 2/3, 4Th St

COMPETITION COMMISSION OF INDIA Case No. 15 of 2018 In Re: Tamil Nadu Consumer Products Distributors Association Informant No. 2/3, 4th Street, Judge Colony, Tambaram Sanatorium, Chennai- 600 047 Tamil Nadu. And 1. Fangs Technology Private Limited Opposite Party No. 1 Old Door No. 68, New Door No. 156 & 157, Valluvarkottam High Road, Nungambakkam, Chennai – 600 034 Tamil Nadu. 2. Vivo Communication Technology Company Opposite Party No. 2 Plot No. 54, Third Floor, Delta Tower, Sector 44, Gurugram – 122 003 Haryana. CORAM Mr. Sudhir Mital Chairperson Mr. Augustine Peter Member Mr. U. C. Nahta Member Case No. 15 of 2018 1 Appearance: For Informant – Mr. G. Balaji, Advocate; Mr. P. M. Ganeshram, President, TNCPDA and Mr. Babu, Vice-President, TNCPDA. For OP-1 – Mr. Vaibhav Gaggar, Advocate; Ms. Neha Mishra, Advocate; Ms. Aayushi Sharma, Advocate and Mr. Gopalakrishnan, Sales Head. For OP-2 – None. Order under Section 26(2) of the Competition Act, 2002 1. The present information has been filed by Tamil Nadu Consumer Products Distributors Association (‘Informant’) under Section 19(1) (a) of the Competition Act, 2002 (the ‘Act’) alleging contravention of the provisions of Sections 3 and 4 of the Act by Fangs Technology Private Limited (‘OP- 1’) and Vivo Communication Technology Company (‘OP-2’) (collectively referred to as the ‘OPs’). 2. The Informant is an association registered under the Tamil Nadu Society Registration Act, 1975. Its stated objective is to protect the interest of the distributors from unfair trade practices and stringent conditions imposed by the manufacturers of consumer products. 3. OP-1 is engaged in the business of trading and distribution of mobile handsets under the brand name ‘VIVO’ and also provide marketing support to promote its products.