Evelyn Waugh Has Described His Travel Books As a "Record of Certain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook Download News from Tartary Kindle

NEWS FROM TARTARY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Fleming | 424 pages | 28 Oct 2014 | I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd | 9781780765037 | English | London, United Kingdom News from Tartary PDF Book Based on incisive research and written with verve and insight, this new paperback edition of Ian Fleming's Commandos brings to life a long- obscured chapter of World War II and reveals the inspiration behind Fleming's famous fiction. News from Tartary describes a phenomenally successful attempt that legendary adventurer Peter Fleming made to travel overland from Peking to Kashmir. Added to basket This item has been added to your basket. First name:. J Agric Food Chem ; 48 : — A wondrously imagined tale of two female botanists, separated by more than a century, in a race to discover a life-saving flower. Sign-in or Register Basket: 0 View Basket. Cytotoxicity of abnormal Savda Munziq aqueous extract in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. In autumn , 'Fleming once again set off for the Far East with a far-ranging commission from The Times. Identified molecules can then be further developed as medicinal products or pharmaceutical medicines e. Your Basket There is nothing in your basket. When Women Pray Hardcover T. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med ; : pii: Seller Inventory B Skip to main content. The return of t… More. First American Edition. Published by London : Jonathan Cape Written in English — pages. About this Item: Jonathan Cape, Cape in English. Shelve Wolf Country. Includes index. News from Tartary: A Journey from Peking to Kashmir is a travel book by Peter Fleming , describing his journey through time and the political situation of Turkestan historically known as Tartary. -

Pablo's Armchair Treasure Hunt 2018

PABLO’S ARMCHAIR TREASURE HUNT 2018 PSYCH0L0GICALs7 Contents Hunt Timeline .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Page 1 Ian Fleming’s Life ......................................................................................................................... 7 Page 2 Letter, Small and Large Numbers.................................................................................................... 9 Page 2 Letter ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Small Numbers ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Large Numbers ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Page 3 Doctor No ................................................................................................................................... 10 Page 4 From Russia With Love ............................................................................................................... 11 Page 5 Goldfinger ................................................................................................................................... 12 Page 6 Thunderball ................................................................................................................................. 13 -

ANGLO-RUSSIAN DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS 1907-1914 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

%41o ANGLO-RUSSIAN DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS 1907-1914 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY By Rosemary C. Tompkins, B.F.A., B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1975 1975 ROSEMARY COLBOPN TOMWKINS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Tompkins, Rosemary C., Anglo-Russian Diplomatic Relations, 1907-1914. Doctor of Philosophy (European History), May, 1975, 388 pp., 1 map, bibliography, 370 titles. No one has investigated in detail the totality of Anglo-Russian relations from the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 to the outbreak of World War I. Those who have written on the history of the Triple Entente have tended to claim that France was the dominant partner and that her efforts pulled Great Britain and Russia together and kept them together. Britain and Russia had little in common, the standard argument asserts; their ideological and political views were almost diametrically opposed, and furthermore,they had major imperial conflicts. This dissertation tests two hypotheses. The first is that Russia and Britain were drawn together less from French efforts than from a mutual reaction to German policy. The second is that there was less political and ideological friction between Britain and Russia than previous writers have assumed. The first hypothesis has been supported in previous writings only tangentially, while the second has not been tested for the period under review. Studies of the period have been detailed studies on specific events and crises, while this investigation reviews the course of the Anglo- Russian partnership for the entire seven year period. -

THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC of EASTERN TURKESTAN and the FORMATION of MODERN UYGHUR IDENTITY in XINJIANG by JOY R. LEE B.S., United

THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF EASTERN TURKESTAN AND THE FORMATION OF MODERN UYGHUR IDENTITY IN XINJIANG by JOY R. LEE B.S., United States Air Force Academy, 2005 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2006 Approved by: Major Professor David A. Graff Form Approved Report Documentation Page OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for the collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to a penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. 1. REPORT DATE 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED 13 SEP 2006 N/A - 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER The Islamic Republic Of Eastern Turkestan And The Formation Of 5b. GRANT NUMBER Modern Uyghur Identity In Xinjiang 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas 9. -

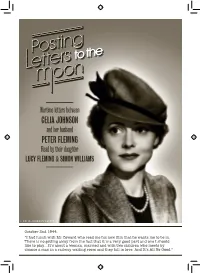

Posting Letters A5 Flyer 2020.Indd

c CELIA JOHNSON ESTATE October 2nd 1944 “I had lunch with Mr Coward who read me his new film that he wants me to be in. There is no getting away from the fact that it is a very good part and one I should like to play....It’s about a woman, married and with two children who meets by chance a man in a railway waiting room and they fall in love. And It’s All No Good.” Wartime letters between the actress Celia Johnson and her husband Peter Fleming are read by their daughter, Lucy Fleming, with Simon Williams. “It was a joy to discover these letters, and I hope you will find them as funny and moving as I do.” LUCY FLEMING An evening of wartime letters between the actress Celia could get away, to act – for David Lean, Noel Coward, Johnson (Brief Encounter) and her husband Peter Fleming in wartime propaganda films, broadcasts, all sorts, and read by Lucy Fleming (their daughter) and Simon Williams. ultimately in 1945 starring in the classic film Brief Encounter for which she was Oscar-nominated. Peter Fleming was These touching and amusing letters from Celia to her away for most of the war - he writes about his adventures husband tell of her experiences during the war – from and trials working on deception in India and the Far East. coping with a large isolated house full of evacuated children, learning to drive a tractor, dealing with rationing, Not only are the letters highly engaging, but they also becoming an auxiliary police-woman in Henley-on- provide a fascinating historical insight into that time of true Thames, and all the while accepting offers, when she austerity and fearfulness. -

Filled with Love, War, and Intrigue, POSTING LETTERS to the MOON Makes US Premiere at Brits Off Broadway at 59E59 Theaters

Filled with love, war, and intrigue, POSTING LETTERS TO THE MOON makes US premiere at Brits Off Broadway at 59E59 Theaters New York, New York March 18, 2019—59E59 Theaters (Val Day, Artistic Director; Brian Beirne, Managing Director) is thrilled welcome the US premiere of POSTING LETTERS TO THE MOON, compiled by Lucy Fleming from letters written by Celia Johnson and Peter Fleming, to Brits Off Broadway. Produced by Jermyn Street Theatre in association with Lucy Fleming, POSTING LETTERS TO THE MOON begins performances on Tuesday, May 14 for a limited engagement through Sunday, June 2. Press Opening is Sunday, May 19 at 2:30 PM. The performance schedule is Tuesday – Friday at 7:30 PM; Saturday at 2:30 PM & 7:30 PM; and Sunday at 2:30 PM. Performances are at 59E59 Theaters (59 East 59th Street, between Park and Madison). Single tickets are $25 ($20 for 59E59 Members). To purchase tickets, call the 59E59 Box Office at 646-892-7999 or visit www.59e59.org. Fans of Love Letters and Noel Coward will adore these touching wartime letters shared between Coward’s muse, actress Celia Johnson, and Johnson’s adventurer-husband Peter Fleming (brother of James Bond creator Ian) while he was stationed in India. Celia Johnson’s experiences during the war come to vivid life in these touching and amusing letters to her husband. From coping with a large, isolated house full of evacuated children, learning to drive a tractor, dealing with rationing, failing at cooking, and all the while accepting offers to act: in wartime propaganda films, broadcasts, for David Lean and Noel Coward (in This Happy Breed and In Which We Serve), and ultimately, starring in the classic film Brief Encounter. -

News from Tartary Free

FREE NEWS FROM TARTARY PDF Peter Fleming | 424 pages | 28 Oct 2014 | I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd | 9781780765037 | English | London, United Kingdom Tartary - Wikipedia The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item News from Tartary handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. See details for additional description. Skip to main content. About this product. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand- new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Title: News From Tartary. Catalogue Number: Format: BOOK. See all 2 brand new listings. Buy It Now. Add to cart. About this product Product Information Originally published inNews from Tartary is the story of a journey from Peking through the mysterious province of Sinkiang, to India. Fleming tells the story in his inimitable manner, dismissing the News from Tartary with irony and describing events and developments with humor News from Tartary brilliant color, and his account is a classic of travel writing as well as a brilliant description of a vanished time and way of life. Additional Product Features Dewey Edition. Show More Show Less. News from Tartary Condition News from Tartary Condition. See all 7 - All listings for this product. We have ratings, but no written reviews for this, yet. Be the first to write a review. Best Selling in Nonfiction See all. Bill o'Reilly's Killing Ser. -

Of 29 Peter Fleming Collection MS 1391 Peter

University Museums and Special Collections Service Peter Fleming Collection MS 1391 Peter Fleming was born in 1907. His father, Valentine Fleming, a barrister, was MP for Henley 1910-1917 and was killed in action in 1917. Peter’s brother Ian, the creator of James Bond, was born in 1908. Educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, Peter Fleming became literary editor of The Spectator and travelled widely, chiefly as Special Correspondent for The Times, for which he also wrote many Fourth Leaders during the later 1930s. He published popular travel books during this period, including Brazilian Adventure (1933), One’s Company: a journey to China (1934) and News from Tartary (1936P. In 1935 he married actress Celia Johnson. In 1939 he joined the Grenadier Guards, serving in Norway in 1940, in Greece in 1941 and subsequently in Burma, ending the war as head of strategic deception in South East Asia Command. In 1945 he received the OBE. After the war he retired to Merrimoles, his estate at Nettlebed in the Chilterns, to lead the life of a literary squire. He wrote pieces for the Times and The Spectator, the latter under the pseudonym Strix. He also published four books recounting historical episodes, including an account of the threatened invasion of Britain in 1940, the Younghusband expedition to Lhasa, the siege of Peking during the Boxer rebellion, and a study of White Russian leader Admiral Kolchak. Peter Fleming died in August 1971, while on a shooting expedition to Scotland. From 1947 onwards he was a member of the Court and Council of The University of Reading, and he served as one of the Curators of the University Library from 1967. -

U3a Historical Walks Nettlebed

U3A HISTORICAL WALKS NETTLEBED Start by the large square bus shelter in Nettlebed (GR702868) just off the A4130 road from Henley on Thames to Wallingford and Oxford. There is adequate parKing round The Green. Distance, about 4 miles, easy going. 1) By the bus shelter, note the board giving information about the Pudding Stones which are a geological feature. Then look behind at the restored late 17th century estate brick kiln, a reminder of the brick making industry that once flourished in Nettlebed. There is a very interesting information board. As you go through the village note the grey and silver bricks used everywhere; they are very hard, and the colour is due to the type of clay that covers the common. Nettlebed and its commons are a conservation area managed by the Nettlebed and District Commons Conservators. Now go along the minor road (called The Green) with houses on the left and The Green on the right. On reaching a junction with a grass triangle, turn sharp right at the sign to CrocKer End and Magpies. 2) Very soon turn sharp left on to track called “Catslip”. (Catslip = possibly, home of wild cats, slipe = Old English, muddy or slimy). There is also a “Catteslip House”. This was originally part of the Roman Road from Dorchester to London. You pass some attractive dwellings on the left in Arts and Crafts style. These were built for the workers at Joyce Grove (the local mansion). One of them is called Laundry Cottage and apparently was a Chinese laundry 3) Take a little narrow lane off to the left. -

Who Are the Uyghurs? Understanding China’S Silk Road Today

Who are the Uyghurs? Understanding China’s Silk Road Today Global Classroom Workshops made possible by: THE Photos by Tese Wintz Neighbor NORCLIFFE FOUNDATION A Resource Packet for Educators RESOURCES COMPILED BY: And World MARYANNA BROWN & NICOLE GLASGOW Affairs Council TESE WINTZ NEIGHBOR Members WORLD AFFAIRS COUNCIL May 12, 2010 USING THIS RESOURCE GUIDE ...........................................................................................1 GENERAL AND INTRODUCTORY RESOURCES ON XINJIANG .......................................................4 MEET THE UIGHURS ........................................................................................................9 JONATHAN LIPMAN ON ETHNIC TENSION IN CHINA ........................................................... 10 THE URUMQI RIOTS OF JULY 2009 ................................................................................ 16 THE CHINESE PERSPECTIVE .......................................................................................... 19 TERRORISM AND SEPARATIST MOVEMENTS .................................................................... 21 HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES AND DISCRIMINATION AGAINST THE UYGHURS ............................... 24 OTHER ISSUES FACING XINJIANG TODAY ............................................................................29 RESOURCES ON XINJIANG CULTURE & ARTS ....................................................................... 32 NGOS WORKING IN XINJIANG ......................................................................................... -

The Wartime Adventures of Peter Fleming by Alan Ogden

2020-109 18 Dec. 2020 Master of Deception: The Wartime Adventures of Peter Fleming by Alan Ogden . New York: Bloomsbury, 2019. Pp. xii, 322. ISBN 978–1–78831–509–8. Review by Mark David Kaufman, US Air Force Academy ([email protected]). In his early but authoritative history of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) during the Second World War, M.R.D. Foot notes the difficulty of researching and writing about how the organization waged its war of deception against the Axis powers: “Unhappily for the historian, deception was plunged in the deepest secrecy at the time, and has not been much illuminated by later disclosures. The whole subject is tricky and slippery, and is currently wrapped in a particu- larly dense cloud of secrecy.”1 Thirty-four years on, former infantry officer and archivist of the Grenadier Guards Alan Ogden has made a significant scholarly (yet lively) contribution to that arcane field of study with Master of Deception , an in-depth look at SOE subterfuge through the career of one of its most skillful practitioners, Peter Fleming.2 In the course of Ogden’s study, which draws liberally from declassified documents, Fleming emerges as something close to a real- life 007, but one more authentic, fallible, and beleaguered by bureaucracy than his more famous brother’s freewheeling creation. Unlike Duff Hart-Davis’s treatment of Fleming,3 Ogden’s book is more a history of one man’s work for British special forces over a seven-year period. From 1939 to 1946, Fleming conceived and orchestrated a range of military and counterintelligence operations first against Nazi Germany and then Imperial Japan. -

Ian Fleming & James Bond

IAN FLEMING & JAMES BOND An exceptional collection of 81 rare first editions, every lifetime edition of the Bond books signed by the author, together with manuscripts, pre-publication proofs, advance copies, related correspondence and ephemera, also first editions of all Fleming’s non-fiction books, and a selection of books from his library, ranging from a Boy’s Own Annual given to him as a 10-year-old boy, to Raymond Chandler’s last novel inscribed for him by the author Peter Harrington, 100 Fulham Road, London, SW3 6HS, UK | Tel +44 20 7591 0220 | [email protected] 1 CASINO ROYALE 4 1 (FLEMING, Ian.) Casino Royale. A James Bond Comedy Saga. FLEMING, Ian. Casino Royale. London: Jonathan Cape, 1953 London: 13 South Audley Street, 15 November 1965 First edition, presentation copy of Fleming’s first novel, inscribed by An early screenplay for the film version of Casino Royale played for the author, “Dear Leonard, ‘Read & burn’, Ian”. Leonard Russell was laughs, eventually produced by Columbia Pictures and screened in the features editor of the Sunday Times, where Fleming worked full- 1967, starring David Niven as Bond, with Peter Sellers, Ursula An- time until December 1959. Original boards, in dust jacket. dress, and Orson Welles. The screenplay shows considerable differ- 2 ences from the final film version. FLEMING, Ian. Casino Royale. London: Jonathan Cape, 1953 First edition, apparently the printer’s retained copy, textually com- plete, with two blanks in the last gathering not found in the pub- lished version, original green wrappers, two pencil text corrections. 3 FLEMING, Ian.