Agriculture Art Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Jul 1

The Fifth Estate Broadcasting Jul 1 You'll find more women watching Good Company than all other programs combined: Company 'Monday - Friday 3 -4 PM 60% Women 18 -49 55% Total Women Nielsen, DMA, May, 1985 Subject to limitations of survey KSTP -TV Minneapoliso St. Paul [u nunc m' h5 TP t 5 c e! (612) 646 -5555, or your nearest Petry office Z119£ 1V ll3MXVW SO4ii 9016 ZZI W00b svs-lnv SS/ADN >IMP 49£71 ZI19£ It's hours past dinner and a young child hasn't been seen since he left the playground around noon. Because this nightmare is a very real problem .. When a child is missing, it is the most emotionally exhausting experience a family may ever face. To help parents take action if this tragedy should ever occur, WKJF -AM and WKJF -FM organized a program to provide the most precise child identification possible. These Fetzer radio stations contacted a local video movie dealer and the Cadillac area Jaycees to create video prints of each participating child as the youngster talked and moved. Afterwards, area law enforce- ment agencies were given the video tape for their permanent files. WKJF -AM/FM organized and publicized the program, the Jaycees donated man- power, and the video movie dealer donated the taping services-all absolutely free to the families. The child video print program enjoyed area -wide participation and is scheduled for an update. Providing records that give parents a fighting chance in the search for missing youngsters is all a part of the Fetzer tradition of total community involvement. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2007 No. 166 House of Representatives PRAYER lic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. The House met at 9 a.m. and was The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. called to order by the Speaker pro tem- Coughlin, offered the following prayer: f pore (Mr. SIRES). Lord God, we seek Your guidance and EFFECTS OF ALTERNATIVE f protection; yet, we are often reluctant MINIMUM TAX to bend to Your ways. Help us to under- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO (Mr. ISRAEL asked and was given stand the patterns of Your creative TEMPORE permission to address the House for 1 hand. In the miracle of life and the minute and to revise and extend his re- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- transformation to light, You show us marks.) fore the House the following commu- Your awesome wonder. Both the chang- Mr. ISRAEL. Madam Speaker, one of nication from the Speaker: ing seasons and the dawning of each the greatest financial assaults on WASHINGTON, DC, day reveal for us Your subtle but con- America’s middle class is the alter- October 30, 2007. sistent movement during every mo- native minimum tax. Originally, it was I hereby appoint the Honorable ALBIO ment of life. SIRES to act as Speaker pro tempore on this meant to ensure that several dozen of Without a screeching halt or sudden day. -

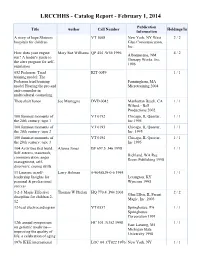

Catalog Report - February 1, 2014

LRCCHHS - Catalog Report - February 1, 2014 Publication Title Author Call Number Holdings/In Information A story of hope Shriners VT 1008 New York, NY West 2 / 2 hospitals for children Glen Communication, Inc. How does your engine Mary Sue Williams QP 454 .W56 1996 4 / 2 Albuquerque, NM run? A leader's guide to Therapy Works, Inc. the alert program for self- 1996 regulation 052 Pederson: Triad KIT 0059 1 / 1 training model: The Pedersen triad training Farmingham, MA model Hearing the pro and Microtraining 2004 anti-counselor in multicultural counseling Thou shalt honor Joe Mantegna DVD 0042 Manhattan Beach, CA 1 / 1 Wiland - Bell Productions 2002 100 funniest moments of VT 0192 Chicago, IL Questar, 1 / 1 the 20th century: tape 1 Inc 1995 100 funniest moments of VT 0193 Chicago, IL Questar, 1 / 1 the 20th century: tape 2 Inc. 1995 100 funniest moments of VT 0194 Chicago, IL Questar, 1 / 1 the 20th century: tape 3 Inc 1995 104 Activities that build: Alanna Jones BF 697.5 .J46 1998 1 / 1 Self-esteem, teamwork, Richland, WA Rec communication, anger Room Publishing 1998 management, self- discovery, coping skills 11 Lessons in self- Larry Holman 0-9648829-0-6 1995 1 / 1 leadership Insights for Lexington, KY personal & professional Wyncom 1995 success 1-2-3 Magic Effective Thomas W Phelan HQ 770.4 .P44 2003 2 / 2 Glen Ellyn, IL Parent discipline for children 2- Magic, Inc. 2003 12 12-lead electrocardiogram VT 0557 Springhouse, PA 1 / 1 Springhouse Corporation 1991 12th annual symposium HC 101 .N352 1998 1 / 1 East Lansing, MI on geriatric medicine— Michigan State improving the quality of University 1998 life: a celebration of aging 1976 IEEE international LOC 04 .CT022 1976 New York, NY 1 / 1 conference on acoustics, Cantebury Press 1976 speech, and signal processing 2004 Aids update Gerald J. -

A Legacy of LIFE & LOVE

1968 ~ 2018 A Half Century of HOPE A Legacy of LIFE & LOVE PREGNANCY CENTER SERVICE REPORT, THIRD EDITION TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2017 Impact at a Glance . 8 1 SECTION I: SERVICE SUMMARY: A LEGACY OF LOVING CARE METHODS . 10 CLIENTS AND VOLUNTEERS . 11 ENHANCING MATERNAL & CHILD HEALTH, WOMEN’S HEALTH, & FAMILY WELL-BEING . 13 MEDICAL SERVICES . 13 Ultrasound Services and Medical Exams . 16 Prenatal Care in Centers . 18 STI/STD Testing and Treatment . 19 COMMUNITY REFERRALS AND PUBLIC HEALTH LINKAGES . 20 CONSULTING AND EDUCATION . 24 Prenatal/Fetal Development Education . 25 Options Consultation . 26 Sexual Risk Avoidance/Sexual Integrity Education . 28 SUPPORT PROGRAMS AND COMMUNITY OUTREACH . 29 Parenting Classes and Education . 29 Material Assistance to Mothers . 31 Community-Based Sexual Risk Avoidance (SRA) Programs . 32 Abortion Recovery . 34 Outreach to Men . 35 2 SECTION II: SPECIAL INITIATIVES AND DEVELOPMENTS ADOPTION . 38 ABORTION PILL RESCUE . 42 MOBILE MEDICAL UNITS (MUs) . 44 OUTREACH TO SPECIAL POPULATIONS . 49 2 ASSISTANCE IN REAL TIME . 54 Heartbeat International’s Option Line . 54 Care Net’s Pregnancy Decision Line . 55 MATERNITY HOMES . 56 3 SECTION III: STANDARDS SECTION IV: PREGNANCY CENTERS AS MODEL 4 COMMUNITY-BASED AND FAITH-BASED ORGANIZATIONS 5 SECTION V: CONCLUSION 6 SECTION VI: NOTES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7 SECTION VII: ENDNOTES CLIENT STORIES AND SPOTLIGHTS Melody . 14 Raven and Martel . 22 Rebecca . 40 Save the Storks . 47 Image Clear Ultrasound (ICU) Mobile . 48 Tina . 58 3 INTRODUCTION c A half century ago, as legal abortion was gaining ground in the United States, a campaign was afoot to offer hope to women considering abortion. -

Lending Library

Lending Library KQED is pleased to present the Lending Library. Created expressly for KQED’s major donors, members of the Legacy Society, Producer’s Circle and Signal Society, the library offers many popular television programs and specials for home viewing. You may choose from any of the titles listed. Legacy Society, Producer’s Circle and Signal Society members may borrow VHS tapes or DVDs simply by calling 415.553.2300 or emailing [email protected]. For around-the-clock convenience, you may submit a request to borrow VHS tapes or DVDs through KQED’s Web site (www.KQED.org/lendinglibrary) or by email ([email protected]) or phone (415.553.2300). Your selection will be mailed to you for your home viewing enjoyment. When finished, just mail it back, using the enclosed return label. If you are especially interested in a program that is not included in KQED’s collection, let us know. However, because video distribution is highly regulated, not all broadcast shows are available for home viewing. We will do our best to add frequently requested tapes to our lending library. Sorry, library tapes are not for duplication or resale. If you want to purchase videotapes for your permanent collection, please visit shop.pbs.org or call 877-PBS-SHOP. Current listings were last updated in February 2009. TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTS 2 DRAMA 13 NEWS/PUBLIC AFFAIRS 21 BAY WINDOW 30 FRONTLINE 32 FRONTLINE WORLD 36 P.O.V. 36 TRULY CA 38 SCIENCE/NATURE 42 HISTORY 47 AMERICAN HISTORY 54 WORLD HISTORY 60 THE “HOUSE” SERIES 64 TRAVEL 64 COOKING/HOW TO/SELF HELP 66 FAQ 69 CHILDREN 70 COMEDY 72 1 ARTS Art and Architecture AGAINST THE ODDS: THE ARTISTS OF THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE (VHS) The period of the 1920s and ‘30s known as the Harlem Renaissance encompassed an extraordinary outburst of creativity by African American visual artists. -

55P.; Major Funding from Sprint PCS, Northwestern Mutual Foundation, and Park Foundation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 073 SE 065 393 TITLE NOVA[R] Fall 2001 Teacher's Guide. INSTITUTION WGBH-TV, Boston, MA. PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 55p.; Major funding from Sprint PCS, Northwestern Mutual Foundation, and Park Foundation. Published semiannually. AVAILABLE FROM WGBH Educational Foundation, 125 Western Avenue, Boston, MA 02134. Web site: http://www.pbs.org/nova/teachers/guide-subscribe.html. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Standards; Elementary Secondary Education; Instructional Materials; *National Standards; *Science Activities; Science Instruction; Science Programs; Television IDENTIFIERS National Science Education Standards; *NOVA (Television Series) ABSTRACT This teacher guide includes activity information for the program NOVA, Fall 2001. Background for each activity is provided along with its correlation to the national science standards. Activities include: (1) "Search for a Safe Cigarette"; (2) "18 Ways To Make a Baby"; (3) "Secrets o'f Mind"; (4) "Neanderthals on Trial";(5) "Life's Greatest Miracle"; (6) "Methuselah Tree"; and (7)"Flying Casanovas." (YDS) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. 0 I II a a II I II EDUCATIONALOfficeU S of DEPARTMENT Educational RESOURCES Research OF EDUCATION and INFORMATION Improvement A0 This Minororiginatingreceived document changes from itCENTER hasthehave person been been (ERIC) reproduced or made organization to as officialdocumentPointsimprove OERIof reproduction view do positionnot or opinionsnecessar orquality policy stated ly represent in this PERMISSIONDISSEMINATEBEEN TO GRANTEDTHIS REPRODUCE MATERIAL BY HASAND 1TO INFORMATIONTHE EDUCATIONAL CENTER RESOURCES (ERIC) _a a 3 Communication and education go hand-in-hand. As a teacher, there is clearly nothing more important than connecting directly with your students. -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

Tracing Bloodlines: Kinship and Reproduction Under Investigation in CSI: Crime Scene Investigation

This is a pre-copy edited version of an article accepted for publication in Journal of Popular Television (Volume 2, Issue 2, October 2014) following peer-review. The definitive publisher authenticated version is available from: http://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/journals/view-Article,id=18491/ Tracing Bloodlines: Kinship and Reproduction Under Investigation in CSI: Crime Scene Investigation SOFIA BULL ABSTRACT This article examines discourses on kinship and reproduction in the forensic crime drama CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (2000–). I argue that the programme stages a visual materialization of genetic kinship in order to assert its importance as a crucial type of forensic evidence, which evokes the traditional Darwinian framework of genealogy for understanding biological kinship as a substantial and enduring trace between generations. However, I show that CSI also participates in contemporary bioethical debates about new genetic and biomedical technologies that increasingly allow us to interfere in the human reproduction process. I conclude that while the programme engages with an emergent post-genomic respatialization of genealogy and acknowledges that the concept of kinship is increasingly being redefined, CSI is still heavily invested in a normative understanding of sexual reproduction as a ‘natural fact of life’ and inadvertently constructs the nuclear family structure as an ideal framework for procreation. KEYWORDS TV; kinship; family; reproduction; genetics; forensic science It is well known that the ties between the television medium and the concept of the family are close and enduring. On the one hand, the family has long been understood as a crucial cultural context for television reception. As Lynn Spigel’s research has shown, the medium quickly became associated with family life and domestic ideals after the Second World War. -

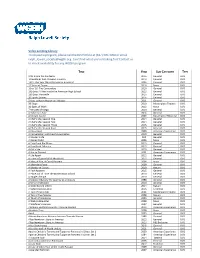

Video Lending Library to Request a Program, Please Call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 Or Email Ralph Lowell [email protected]

Video Lending Library To request a program, please call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 or email [email protected]. Can't find what you're looking for? Contact us to check availability for any WGBH program. TITLE YEAR SUB-CATEGORY TYPE 9/11 Inside the Pentagon 2016 General DVD 10 Buildings that Changed America 2013 General DVD 1421: The Year China Discovered America? 2004 General DVD 15 Years of Terror 2016 Nova DVD 16 or ’16: The Contenders 2016 General DVD 180 Days: A Year inside the American High School 2013 General DVD 180 Days: Hartsville 2015 General DVD 20 Sports Stories 2016 General DVD 3 Keys to Heart Health Lori Moscas 2011 General DVD 39 Steps 2010 Masterpiece Theatre DVD 3D Spies of WWII 2012 Nova DVD 7 Minutes of Magic 2010 General DVD A Ballerina’s Tale 2015 General DVD A Certain Justice 2003 Masterpiece Mystery! DVD A Chef’s Life, Season One 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Two 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Three 2015 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Four 2016 General DVD A Class Apart 2009 American Experience DVD A Conversation with Henry Louis Gates 2010 General DVD A Danger's Life N/A General DVD A Daring Flight 2005 Nova DVD A Few Good Pie Places 2015 General DVD A Few Great Bakeries 2015 General DVD A Girl's Life 2010 General DVD A House Divided 2001 American Experience DVD A Life Apart 2012 General DVD A Lover's Quarrel With the World 2012 General DVD A Man, A Plan, A Canal, Panama 2004 Nova DVD A Moveable Feast 2009 General DVD A Murder of Crows 2010 Nature DVD A Path Appears 2015 General -

Philip G. Zimbardo Papers SC0750

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7f59s371 Online items available Guide to the Philip G. Zimbardo Papers SC0750 Jenny Johnson & Daniel Hartwig Department of Special Collections and University Archives March, 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Philip G. Zimbardo SC0750 1 Papers SC0750 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Philip G. Zimbardo papers creator: Zimbardo, Philip G. Identifier/Call Number: SC0750 Physical Description: 256 Linear Feet182 boxes Date (inclusive): 1953-2017 Abstract: The materials consist of research and teaching files, professional files and correspondence, audiovisual materials, professional papers and articles, and materials documenting the Stanford Prison Experiment. Abstract: The materials consist of research and teaching files, professional files and correspondence, audiovisual materials used in the classroom, professional papers and articles, and materials documenting the Stanford Prison Experiment. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36-48 hours in advance. For more information on paging collections, see the department's website: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/spc.html. Acquisition Information This collection was donated by Philip G. Zimbardo to Stanford University, Special Collections in multiple accessions from 2011-2017. Information about Access Boxes 9 and 9A in Series 6 (Stanford Prison Experiment) are restricted to protect participant privacy. Files in Series 9 (Restricted Materials) are restricted for 75 years from date of creation. Otherwise the collection is open for research; audiovisual materials are not available in original format, and must be reformatted to a digital use copy. -

5 April, 2001 List Is Arranged Alphabetically by Title. Please Consult HOLLIS Catalog for Additional Information. Videos Are

VIDEOS IN THE COLLECTION OF THE TOZZER LIBRARY OF THE HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY 5 April, 2001 List is arranged alphabetically by title. Please consult HOLLIS catalog for additional information. Videos are for in-house use only. Holders of Officer ID cards may charge videos out for a two-day loan period. Recently received videos (Dec. 2000 – March 2001) A.V. J.C. G 221 BPS8487 Gate to the Buddha / a video by Wen-jie Qin ; produced at The Film Study Center, Harvard University. A portrayal of how Chinese Buddhists celebrate death as a passage to a world of wonder and mystery. Set on the sacred mountain Emei Shan in south- west China, the film centers on the deaths of three elderly monks; and explores with the monks, nuns, and lay devotees what it means to die and how the Pure Land, Zen, and Tantric tradition prepare them for making that journey. A.V. C.A.3 L 899 BPP9299 Lost king of the Maya / written, produced and directed by Gary Glassman ; WGBH Educational Foundation. Travels back 1600 years to show the ancient Mayans' intellect, astronomical abilities and complex culture. A team of archaeologists and historians piece together an image of the rise and fall of Copan, a site in Honduras, and of Yax K'uk Mo, a Mayan king. A.V. C.A.3 L 899 2001 BPV1595 Lost king of the Maya / written, produced and directed by Gary Glassman ; WGBH Educational Foundation. Travels back 1600 years to show the ancient Mayans' intellect, astronomical abilities and complex culture. A team of archaeologists and historians piece together an image of the rise and fall of Copan, a site in Honduras, and of Yax K'uk Mo, a Mayan king. -

Bibliography"

3/7/2016 Job summary for "Bibliography" Bibliography Sorted by Call Number / Author. VID 133 WIT The Witches of Salem : the horror and the hope. Los Angeles, CA : Learning Company of America, 1986. A portrayal of the witchcraft trials of Salem, Massachusetts in 1692. Attempts to give an understanding of the political, psychological, and religious background of the trials and of the consequences of this episode on American history. VID 292 MYT Mythology : gods and goddesses. Mt. Kisco, NY : Guidance Associates, 1981. VID 292 MYT Mythology. New York : Company, c1983. VID 305.8 SEP Separate but equal. Special release. Los Angeles, CA : Republic Pictures Home Video, c1991. Sidney Poitier, Burt Lancaster, Richard Kiley. Dramatization of the events leading to the landmark Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation, with a special introduction by Sidney Poitier. VID 306.8 CHI Fathers too soon?. 1987. VID 306.8 CHI Children having children. Washington, D.C : Children's Defense Fund. Several pregnant and parenting teenagers describe their feelings and experiences with pregnancy and its consequences. VID 323 EYE Eyes on the prize : America's civil rights years 1954 to 1965. v.1. Awakenings (19541956) v.2. Fighting Back (19571962) v.3. Ain't Scared of Your Jails (19601961) v.4. No Easy Walk (19611963) v.5. Mississippi: Is This America? (19621964). VID 323 EYE Eyes on the prize II : America at the racial crossroads, 19651985. Alexandria, VA : Distributed by PBS Video, c1993. [1] The time has come (19641965). Two societies (19651968) [2] Power! (19661968). The promised land (19671968) [3] Ain't gonna shuffle no more (19641972).