Chicago IL 9.5.97 the Circle Closes We Started the Trophy Awards With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gold Wing What Lies Beyond?

Page short by .125 TRIM 11.875 Held at right. large image on the left moved .0625 to the right 2018 WHAT LIES BEYOND? GOLD WING What lies over the horizon? Beyond our town, our state? Beyond the predictable, the expected? And what’s the best way to experience it? We ride motorcycles because they’re such engaging, active, personal vehicles. Travel the same roads in a car and on a bike, eat at the same restaurants, see the same sights, and then tell us which trip is the most memorable. Honda’s 2018 Gold Wing® is an all-new motorcycle this year, designed to put you more in touch with the essential experience of riding. Changing a bike as good and as refined as a Gold Wing isn’t something you undertake lightly. So we set out to improve the newest model in every category: Engineering. Handling. Technology. Comfort. Performance. The new Gold Wing is lighter, more powerful, more nimble, and more engaging. It’s a better motorcycle in every way. What lies beyond? Ride there and find out. YEARS OF ADVENTURE. THE FIRST GOLD WING—THE 1975 GL1000—WAS REVOLUTIONARY, A MOTORCYCLE THAT OFFERED SUPERBIKE-LEVEL POWER, INCREDIBLE SMOOTHNESS, LIQUID COOLING, SHAFT DRIVE, AND A HOST OF TECHNICAL INNOVATION UNMATCHED AT THE TIME IN THE MOTORCYCLING WORLD. RIDERS ACROSS THE GLOBE RECOGNIZED THE GENIUS IN THIS MACHINE, BUT ESPECIALLY RIDERS WHO WANTED TO COVER LONG DISTANCES. AND SO THE GOLD WING BECAME A TOURING ICON. OVER THE YEARS WE ADDED BODYWORK, SADDLEBAGS, AND INCREASED THE ENGINE SIZE. NOW IT’S TIME TO GO BACK TO OUR ROOTS, TO THE KIND OF PERFORMANCE AND HANDLING THAT MADE THOSE FIRST GOLD WINGS SUCH AWESOME BIKES. -

Gold Wing Tour

Gold Wing Tour 22 Eight-year extended model 1 Electronics package includes: warranty available - Bluetoot h ® connectivity and USB integration Electric windscreen (tall) 2 - SiriusXM ® satellite radio with traffic update* - Next-generation navigation system 19 Integrated - Apple CarPla y™ integration with Siri voice control** Thin-Film-Transistor (TFT) rear speakers • LCD instrument screen 3 Four selectable Ride Modes: 20 Heated grips and seats Tour, Sport, Rain and Econ 4 • 21 Airbag model SMART Key ignition • available 18 LED lighting • and Bag Lock system 5 (taillight, • headlight, • • • license Front-Link Suspension plate and • 6 turn signals) • • 17 Combined • Anti-Lock Braking • System (C-ABS) • and Hill Start • Assist (HSA) • • Aluminum 200/55-16 rear tire 13 Aluminum • wheels with 16 • frame 7 TPMS 1833cc six-cylinder • • 12 Forward and Reverse 10 engine 15 Honda Selectable walking speed Torque Control (HSTC) (DCT models) Six-speed manual transmission with slipper clutch, or seven-speed automatic 14 Shaft-drive Aluminum swingarm 11 9 Dual Clutch Transmission (DCT) * Three months free SiriusX M® with purchase of optional XM antenna. ** Requires compatible iPhone and helmet equipped with Bluetooth ® headset Electronically selectable spring-preload rear suspension and microphone. (SENA 10S/20S headset recommended.) 8 PAGE | 1 Gold Wing/Gold Wing Tour The following charts are the first step in learning about the differences of the new Honda Gold Wing and Gold Wing Tour models. Knowing the differences allows you to confidently recommend the perfect bike for each customer’s use and budget. Use this chart as a tool to help get new salespeople up to speed quickly on the new models or as a quick reference guide for experienced sales associates. -

Take Freedom for a Ride

> 2017 MOTORCYCLES / SCOOTERS TAKE FREEDOM FOR A RIDE. > 2017 MOTORCYCLES / SCOOTERS GREAT RIDES START WITH GREAT BIKES. Nobody’s done more to make motorcycles more fun to ride than Honda. So what’s your idea of fun? Touring cross country wrapped in comfort and luxury? Carving through a twisty canyon road? Cruising the boulevard? Saving time, money, and headaches on your daily commute? At Honda, our streetbike lineup has something for everyone. Our philosophy has always been to design our bikes around the rider. In the 1960s, we introduced innovations like electric starters and disc brakes. Now we offer features like Honda’s Automatic Dual-Clutch Transmissions (DCT), anti-lock brakes, and seamless torque control. No matter which Honda you choose, there’s never been a better time to ride. FOR MORE INFO & SPECS > powersports.honda.com 01 1832cc SIX-CYLINDER ENGINE The Gold Wing’s six-cylinder engine is legendary for its smoothness. > TOURING A big reason for that is the horizontally opposed design, unique to the Gold Wing line. POWER. STYLE. 02 NAVIGATION AND TRIP PLANNER You can plan trip routes on your computer and upload them into your Gold Wing’s available navi system. There are even available XM® Traffic COMFORT. FREEDOM. and Weather functions. 01 02 Generations of riders know Honda’s Gold Wing® is legendary as the ultimate luxury touring motorcycle. Nothing is as refined as a Gold Wing, and a big part of that is its six-cylinder, 1832cc horizontally opposed engine. Looking for something smaller? Then check out the CTX®700, an excellent choice for both weekend trips and daily riding. -

Gold Wing Brochure

GOLD WING WHAT LIES BEYOND? What lies over the horizon? Beyond our town, our state? Beyond the predictable, the expected? And what’s the best way to experience it? We ride motorcycles because they’re such engaging, active, personal vehicles. Travel the same roads in a car and on a bike, eat at the same restaurants, see the same sights, and then tell us which trip is more memorable. Honda’s Gold Wing® motorcycle is designed to put you in touch with the essential experience of riding. Changing a bike as good and as refined as a Gold Wing isn’t something you take lightly. So, we set out to improve the newest model in every aspect: engineering, handling, technology, comfort, performance. The Gold Wing is lighter, more powerful, more nimble, and more engaging. It’s a better motorcycle in every way. What lies beyond? Ride there and find out. YEARS OF ADVENTURE The first Gold Wing—the 1975 GL1000—was revolutionary. A motorcycle that offered superbike-level power, incredible smoothness, liquid cooling, shaft drive, and a host of technical innovations unmatched at the time in the motorcycling world. Riders across the globe recognised the genius in this machine, but especially riders who wanted to cover long distances even more so, that’s why the Gold Wing became a touring icon. Over the years we added bodywork, saddlebags, and increased the engine size. Now it’s time to go back to our roots, to the kind of performance and handling that made those first Gold Wings such awesome bikes. Hang on, and enjoy the ride! MORE THAN WHAT MEETS THE EYE TECHNOLOGY When the time came to design the Gold Wing engine, we had four goals. -

GL1800-Accessories-19-Web.Pdf

2 TOURING ACCESSORIES 2019 CATALOGUE ACCESSORIES GOLD WING / GOLD WING TOURER / TOURER DCT KEY FEATURES PGM FI HECS3 ABS HISS LED LIGHTS EURO 4 DCT kW Nm mm 93 @ 5,500 rpm 170 @ 4,500 rpm 745 Max Power Output Max Torque Seat Height When long-distance motorcycling Hbecame a reality Honda’s Gold Wing is one of the most iconic names in biking history. Revealed back in 1975, the Gold Wing became through the years, synonym of long-distance motorcycling. The world’s longest motorcycle ride, spanning 10 years, 279 countries and a total distance of 457,000 miles (735,000 km) was achieved by an Argentinian rider on a 1980 At the beginning, the Gold Wing was powered by Honda Gold Wing GL1100. Source: Scotto, Emilio (2007), The Longest Ride: My Ten-Year 500,000 Mile Motorcycle Journey, a liquid-cooled-flat-four engine with a 999cc displacement. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company, ISBN 9780760326329 3 GOLD WING LUGGAGE Trunk Lights Kit Chrome Trunk Rack Kit 08ESY-MKC-LED18 08L70-MKC-C00 Pack containing all accessories to install the Trunk inner lamp Chrome Rack to be installed on the Trunk of the Gold Wing. Adds style and functionality, and the LED stop light when Trunk is installed on the Gold Wing. featuring a chrome-plated steel rack with rubber inserts for improved appearance while - Trunk Sub Harness (08E86-MKC-A00) adding carrying capacity. Features a 2.3kg weight limit. - Chrome Trunk Rack (08L70-MKC-C00) - Trunk Inner Lamp Kit (08U74-MKC-A00) - LED H/M Stop Light Kit (08U76-MKC-A00) Trunk Inner Bag Rear Trunk Matt 08L00-MKC-A00 08P00-MKC-A00 Convenient abrasion-resistant ballistic nylon trunk liner makes packing Plush premium-quality carpeting with slip-resistant easier and protects your belongings when traveling. -

Endless Freedom

EXPERIENCE ENDLESS FREEDOM This is where it all begins. A whole new world of endless freedom is out there, just waiting to be discovered — creating everlasting memories forever etched into your mind. It’s in our nature to explore what lies beyond, to seek the unexpected and to experience life in the most vivid ways imaginable — one great ride at a time. GOLD WING 2019 3 IT’S 1975: THE LEGEND TAKES FLIGHT They say timeless things never get old. Since making its debut back in 1975, the original Honda Gold Wing — known then as the Honda GL1000 — played a major role in establishing the motorcycle touring category. The Gold Wing went on to not only set the standard to which all future touring motorcycles continue to be compared to today, but also earn itself a highly TODAY, THE LEGEND coveted reputation among long-distance riders for impeccable luxury, advanced technology and proven performance. Over the GOES BEYOND 1975 – GL1000 GOLD WING years many things sure have changed, but the legendary Gold Touring is born. And no one saw it coming. Powered by a 999 cc liquid cooled horizontally Discover the true feeling of freedom with the Honda Gold Wing. Representing one of the greatest achievements in motorcycle touring Wing remains our ultimate performance touring machine, well opposed four-cylinder engine, the original GL1000 marked a significant shift in moto performance and technology, the Gold Wing is destined to add a new chapter to the ever-evolving Honda legacy. Get ready to experience a deserving of its authentic flagship status decades later. -

Tarifa Importación Bike.It 2015

TARIFA BIKE.IT 2015 REF. DESCRIPCION P.V.P. sin IVA. 7010309 SWING-ARM SLIDERS BLACK STP 8MM (1.25 PITCH) 20,77 € 7010609 SWING-ARM SLIDERS BLACK STP 6MM (1.00 PITCH) 20,77 € 7010709 SWING-ARM SLIDERS BLACK STP 10MM (1.50 PITCH) 20,77 € 7503109 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA CUT-TYPE CBR600 FM-FW 91-98 51,97 € 7503209 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA CUT-TYPE CBR600 FX-FY 99-00 CBR600 F1, 2, 4 FS1, FS2 01-06 51,97 € 7503210 BIKETEK CRASH PROTECTOR HONDA CBR500R 13> BLACK NO CUT 90,97 € 7503309 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA CUT-TYPE CBR600RR 03-06 51,97 € 7503319 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA NO-CUT CBR600RR 07-08 109,17 € 7503329 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA CUT-TYPE CBR600RR 07-08 51,97 € 7503340 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA CUT-TYPE CBR600RR 09- 51,97 € 7503360 BIKETEK CRASH PROTECTOR HONDA CBR600RR 13> NO CUT 77,97 € 7503409 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA CUT-TYPE CBR900RR R-X 93-99 51,97 € 7503509 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA NO-CUT CBR900RR Y/1 00-01 900RR 2/3 02-03 51,97 € 7503609 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA CUT-TYPE VTR1000 SP1 (RC51) 00-01 57,17 € 7503709 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA CUT-TYPE VTR1000 SP2 (RC51) 02-06 51,97 € 7503809 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA NO-CUT CBR1000RR 04-05 77,97 € 7503819 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA NO-CUT CBR1000RR 06-07 77,97 € 7503900 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA NO-CUT CB1000R 08- 51,97 € 7503919 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA NO-CUT CB600 HORNET 07- CBF600 08- 51,97 € 7503929 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA NO-CUT CB600 HORNET 06- CBF600 04-07 51,97 € 7503931 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA NO-CUT CBF1000F 2010 51,97 € 7503939 FRAME SLIDERS BLACK HONDA NO-CUT -

Motorcycle Antilock Braking Systems and Fatal Crash Rates: Updated Results

Motorcycle antilock braking systems and fatal crash rates: updated results August 2021 Eric R. Teoh Contents ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 4 METHODS ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 RESULTS ...................................................................................................................................................... 11 DISCUSSION ................................................................................................................................................. 15 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................... 17 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................................... 17 2 Abstract Introduction: Antilock braking systems (ABS) prevent wheels from locking during hard braking and have been shown to reduce motorcyclists’ crash risk. ABS has proliferated in the United States fleet, and the objective of the current study was to update the effectiveness estimate for ABS with additional years of data and a broader variety -

Touring Accessories Catalogue 2019 2 Touring Accessories 2019 Catalogue

TOURING ACCESSORIES CATALOGUE 2019 2 TOURING ACCESSORIES 2019 CATALOGUE MAKE YOUR HONDA TRULY YOURS What is better than Honda Genuine Accessories to make your Honda truly yours? For extra luggage capacity, improved comfort, rugged protections, extended performance or just an even better looking bike, we have everything covered. Built with the same attention to details than your Honda, supported by a 2-year warranty (*), our accessories will suit perfectly your bike and add to its value. Ask your local Honda Dealer. He knows how to make your Honda Touring bike truly yours. Prices shown are inclusive of fitting and labour. CONTENTS 03 GOLD WING / GOLD WING TOURER / TOURER DCT 12 VFR800F (*) 2-year warranty applicable only on genuine accessories. Special conditions apply on accessories developed with Honda partners. Ask your local dealer for more details. 1 2 TOURING ACCESSORIES 2019 CATALOGUE ACCESSORIES GOLD WING / GOLD WING TOURER / TOURER DCT KEY FEATURES PGM FI HECS3 ABS HISS LED LIGHTS EURO 4 DCT kW Nm mm 93 @ 5,500 rpm 170 @ 4,500 rpm 745 Max Power Output Max Torque Seat Height When long-distance motorcycling becameH a reality Honda’s Gold Wing is one of the most iconic names in biking history. Revealed back in 1975, the Gold Wing became through the years, synonym of long-distance motorcycling. The world’s longest motorcycle ride, spanning 10 years, 279 countries and a total distance of 457,000 miles (735,000 km) was achieved by an Argentinian rider on a 1980 At the beginning, the Gold Wing was powered by Honda Gold Wing GL1100. -

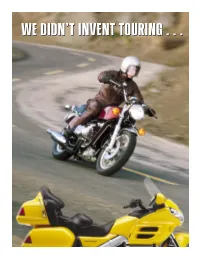

We Didn't Invent Touring

WEWE DIDN’TDIDN’T INVENTINVENT TOURINGTOURING .. .. .. WE JUST REINVENTED IT. AGAIN. Ever since the motorcycle was invented, riders have taken to the open road to single-side swingarm, the new Gold Wing 1800 explodes existing touring seek new vistas, new challenges. For subsequent decades, riders immersed them- limitations. The first true high-performance luxury motorcycle, the new Gold selves in the exhilaration of their new sport, but often endured discomfort and Wing balances luxury appointments with a level of sporting prowess never hardship in exchange for the thrills of long-distance travel. before seen in motorcycling. Then in 1975, Honda introduced the first Gold Wing®. And the motorcycling By striking an artful blend between transcontinental comfort and a decidedly world has never been the same. From the beginning, the Gold Wing offered rid- athletic persona, the 2001 Gold Wing powers down a road that is at once new yet ers an innovative combination of high performance, and remarkable comfort familiar, a path that leads the Gold Wing back to its high-performance origins. and reliability–a combination of attributes that were rare at the time. These For more than 25 years, the Gold Wing has redefined the art of long-distance rid- unique capabilities opened up new riding possibilities for a broader range of ing. Now the new Gold Wing 1800 has reinvented touring. Again. enthusiasts than ever before. 1972 A design team is established, led by Soichiro Irimajiri, who headed up design of As 2001 dawns we see the new Gold Wing, an icon reborn. Endowed with an the five- and six-cylinder road racing engines of the 1960s. -

Touring Accessories

000478 TOURING ACCESSORIES EXHAUST TIRES & ACCESSORIES WINGLEADER® MIRROR HOUSINGS FOR HONDA GL1800 GOLD WING 01-08 LUGGAGE •Chrome plastic mirror housings add a distinctive custom touch •Designed to replace the OEM mirror housing SPORTBIKE •Use stock mirror components ACCESSORIES •Sold in pairs CRUISER SUG. RETAIL..............$74.95 PART # 0641-0058 ACCESSORIES TOURING ACCESSORIES WINGLEADER® WINGLEADER® SECURITY MIRROR ACCENTS SADDLEBAG & AUDIO FOR GL1800 MOLDING GENERAL GOLD WING 01-08 ACCESSORIES FOR HONDA GL1800 •Chromed plastic accents for GOLD WING 01-08 turn signal side of mirror FAIRINGS & BODY •Install in minutes with adhesive •Chrome-plated, tape (included) injection- molded ABS SEATS SUG. RETAIL..............$29.95 PART # 1901-0025 plastic accents •Adds style to GL1800 ® saddlebags HANDLEBARS WINGLEADER & CONTROLS SADDLEBAG SUG. RETAIL..............$62.95 PART # DS715086 SCUFF COVERS ® LIGHTING FOR HONDA GL1800 WINGLEADER GOLD WING 01-08 TRUNK KEY ACCENT ELECTRICAL •Chrome cover keeps passenger’s FOR HONDA GL1800 heels from scratching saddlebags GOLD WING 01-08 •Contour design means easy •Accent gives a custom look and SPROCKETS installation and a factory fit protects from scratches •Sold in pairs •Chrome finish CHAINS SUG. RETAIL..............$79.95 PART # DS715088 •Simple installation with included adhesive tape SUG. RETAIL..............$11.95 PART # 0521-0615 WINGLEADER® BRAKES TRUNK HANDLE WINGLEADER® WITH LED MIRROR TRIM SUSPENSION FOR HONDA GL1800 FOR HONDA GL1800 GOLD WING 01-08 GOLD WING 01-08 ENGINE •Plastic chrome trunk •Add a custom touch handle provides extra lift support •Plastic with chrome finish •Red LEDs can be used as auxiliary running or brake lights •Install quickly using included FUEL SYSTEMS •Minor drilling required for installation adhesive tape •Includes instructions and installation hardware •Sold in pairs LUBES SUG. -

2019 Motorcycle Tire Data Book Version 3.0 TABLE of CONTENTS SPORT/SPORT TOURING P

2019 Motorcycle Tire Data Book Version 3.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPORT/SPORT TOURING P. 10 CRUISERS P. 18 SCRAMBLERS P. 26 ADVENTURE/DUAL SPORT P. 28 OFF-ROAD/ENDURO P. 34 TUBES P. 40 SCOOTER P. 42 OE FITMENTS P. 44 FITMENT GUIDE P. 48 NEW TIRES FOR 2019 ADVENTURE/DUAL SPORT OFF-ROAD/ENDURO Designed with the Adventure The BATTLECROSS E50 is the enthusiast in mind. This aggressive most versatile off-road tire in the Adventure tire is the perfect BATTLECROSS line-up. The E50 is compliment to your modern built specifically with the hardcore Adventure motorcycle, and delivers Enduro rider in mind, where the rider uncompromising performance both must traverse multiple surfaces in on and off-road. one ride. *DOT Approved FRONT REAR FRONT REAR SCRAMBLER SPORT The all new AX41S was developed The BATTLAX HYPERSPORT S22 is specifically for the rider who wants Bridgestone’s premier tire for the classic Scrambler looks, but still modern street sport bike. Starting desires Bridgestone performance where the S21 left off, the S22 has and capability. The AX41S is truly improved both the compounds and where form meets function. pattern design to promote better handling in all conditions without compromising wear. FRONT REAR FRONT REAR 4 5 PRODUCT POSITIONING POSITIONING 1000cc I 600cc I 400cc I 250cc I 125cc I 50cc RACE [ SPORT [ SPORT/ SPORT TOURING CRUISER SCRAMBLER ADVENTURE/ DUAL SPORT OFF-ROAD/ [ ENDURO SCOOTER [ 7 TECHNOLOGY MS•BELT 3D CTDM OUTSIDE BEAD FILLER 5LC (TRIPLE COMPOUND) MSB construction means that a continuous single 3D CTDM is Bridgestone’s newest automated tire The latest generation outside bead filler Offers ideal grip performance demanded in all riding strand is wrapped around the circumference of design technology.