Overview of the Key Aspects and History of the Bachelor of Music in Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6Th Annual Kaiser Permanente San Jose Jazz Winter Fest Presented By

***For Immediate Release: Thursday, January 14, 2016*** 6th Annual Kaiser Permanente San Jose Jazz Winter Fest Presented by Metro Thursday, February 25 - Tuesday, March 8, 2016 Cafe Stritch, The Continental, Schultz Cultural Arts Hall at Oshman Family JCC (Palo Alto), Trianon Theatre, MACLA, Jade Leaf Eatery & Lounge and other venues in Downtown San Jose, CA Event Info: sanjosejazz.org/winterfest Tickets: $10 - $65 "Winter Fest has turned into an opportunity to reprise the summer's most exciting acts, while reaching out to new audiences with a jazz-and-beyond sensibility." –KQED Arts National Headliners: John Scofield Joe Lovano Quartet Regina Carter Nicholas Payton Trio Delfeayo & Ellis Marsalis Quartet Marquis Hill Blacktet Bria Skonberg Regional Artists: Jackie Ryan J.C. Smith Band Chester ‘CT’ Thompson Jazz Beyond Series Co-Curated with Universal Grammar KING Kneedelus Kadhja Bonet Next Gen Bay Area Student Ensembles Lincoln Jazz Band SFJAZZ High School All Stars Combo Homestead High School Jazz Combo Los Gatos High School Jazz Band San Jose State University Jazz Combo San Jose Jazz High School All Stars San Jose, CA -- Renowned for its annual Summer Fest, the iconic Bay Area institution San Jose Jazz kicks off 2016 with dynamic arts programming honoring the jazz tradition and ever-expanding definitions of the genre with singular concerts curated for audiences within the heart of Silicon Valley. Kaiser Permanente San Jose Jazz Winter Fest 2016 presented by Metro continues its steadfast commitment of presenting a diverse array of some of today’s most distinguished artists alongside leading edge emerging musicians with an ambitious lineup of more than 25 concerts from February 25 through March 8, 2016. -

Jazz Combofest

Monday–Friday, December 7–11, 2020 Livestream from MSM Jazz ComboFest Monday, December 7 PROGRAM 3:15 PM Theo Bleckmann Ensemble Miriam Crellin, voice Rostrevor, Australia Nick Creus, guitar Rye, New York Rocco Dapice, piano Ardsley, New York April Varner, voice Sylvania, Ohio Tammy Huynh, voice Ambler, Pennsylvania Shimone Gambourg, double bass Brooklyn, New York Joshua Green, drums Houston, Texas SET LIST/SELECTIONS Dream State Shimon Gambourg/April Varner The One I’ve Waited For Music by Guy Wood, Vocalese by April Varner She Will Lead the Way Music and Lyrics by Rocco Dapice and April Varner For Lonely Nights Tammy Huynh I Spend My Days Rocco Dapice/Nicholas Creus/Tammy Huynh Still I Ask Miriam Crellin (arr. Shimon Gambourg) Joy Miriam Crellin Early Pennsylvania Miriam Crellin 4:15 PM Scott Wendholt Ensemble Henry Sherris, trumpet Wellington, New Zealand Estes Noe Cantarero-George, trombone Alexandria, Virginia Zoe Harrison, double bass Davis, California Audrey Pretnar, guitar Mohegan Lake, New York Kabelo Mokhatla, drums Kempton Park, South Africa SET LIST/SELECTIONS A New Beginning Estes Noe Cantarero-George Simplicity Kabelo Boy Mokhatla Woodchuck Waltz Audrey Meying Pretnar Joy Spring Clifford Brown Mirage Zoe Harrison 5:15 PM Rogerio Boccato Ensemble Evan Amoroso, bass trombone Harrisonburg, Virginia Evan Arntzen, clarinet New York, New York Shimone Gambourg, double bass Brookyln, New York Joshua Green, drums Houston, Texas Ethan Fisher, vibraphone Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Kellin Hanas, trumpet Wheaton, Illinois Emmett Sher, guitar Staten Island, New York Rogerio Boccato, percussion (MSM faculty member) SET LIST/SELECTIONS A Rã João Donato Bebê Hermeto Pascoal Fato Consumado Djavan A Porta Dori Caymmi Coisa No. -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Golden Ear Award Winners Photo by Daniel Sheehan 2 • EARSHOT JAZZ • April 2014 EARSHOT JAZZ LETTER from the DIRECTOR a Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community

A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community April 2014 Vol. 30, No. 04 EARSHOT JAZZSeattle, Washington Golden Ear Award Winners Photo by Daniel Sheehan 2 • EARSHOT JAZZ • April 2014 EARSHOT JAZZ LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Executive Director John Gilbreath Managing Director Karen Caropepe Think Globally, JAM Locally Earshot Jazz Editor Schraepfer Harvey Contributing Writers Katy Bourne, Jessica April is becoming the month for Davis, Steve Griggs, Peter Monaghan global jazz awareness, with ma- jor organizations and institutions Calendar Editor Schraepfer Harvey bringing new muscle to hold up the Calendar Volunteer Tim Swetonic torch long carried by jazz-loving in- Photography Daniel Sheehan dividuals. Layout Caitlin Peterkin The Smithsonian Institution des- Distribution Karen Caropepe, Dan Wight and ignated April as Jazz Appreciation volunteers Month (JAM) in 2001, organizing Send Calendar Information to: annual campaigns to honor jazz as JOHN GILBREATH PHOTO BY BILL UZNAY 3429 Fremont Place N, #309 an “original American art form.” organization, we can’t help imagin- Seattle, WA 98103 This year, the Museum of American ing instead how many artists those fax / (206) 547-6286 History celebrates JAM with “Jazz budgets could bring to new stages email / [email protected] Alchemy: A Love Supreme,” pay- in schools and community centers Board of Directors Bill Broesamle, ing tribute to John Coltrane and the 50th anniversary of his master- around the region, ultimately let- (president), Femi Lakeru (vice-president), ting jazz speak for itself. Sally Nichols (secretary), George Heidorn, work, A Love Supreme. UNESCO brought jazz appre- This April, we ask that you think Ruby Smith Love, Hideo Makihara, Kenneth of Earshot Jazz in the same spirit as W. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

An Analysis of Nate Wood's Drumming on The

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2018 Neoteric Drum Set Orchestration: An analysis of Nate Wood’s drumming on the music of Tigran Hamasyan Ryan George Daunt Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Daunt, R. G. (2018). Neoteric Drum Set Orchestration: An analysis of Nate Wood’s drumming on the music of Tigran Hamasyan. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1519 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1519 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Press Release

Theo Bleckmann Performs Hello Earth! – The Music of Kate Bush Presented by Bang on a Can and the Jewish Museum Photo by Lynne Harty available in high resolution upon request Thursday, November 14, 2019 at 7:30pm Scheuer Auditorium at the Jewish Museum | 1109 5th Ave at 92nd Street | New York, NY Tickets: $20 General; $16 Students and Seniors; $12 Jewish Museum Members Available at www.thejewishmuseum.org. Includes museum admission. New York, NY – Bang on a Can and the Jewish Museum’s 2019-2020 concert season continues on Thursday, November 14, 2019 at 7:30pm at the Jewish Museum (1109 Fifth Avenue at 92nd Street). Grammy-nominated jazz singer, new music composer, and long time collaborator with Bang on a Can, Theo Bleckmann takes on the mysterious songbook of British pop icon Kate Bush in a project entitled Hello Earth! – The Music of Kate Bush that goes beyond re-creating her music to further realms of sound and interpretation. Joining him on this performance are long-time collaborators percussionist Ben Wittman, bassist Chris Tarry, and keyboardist Henry Hey, along with special guest, multi-instrumentalist Caleb Burhans on viola, guitar, and laptop. Of his 2011 recording for Winter & Winter, The New York Times writes, “Bleckmann treats Bush's music as he would that of Charles Ives, Thelonious Monk, George Gershwin, Guillaume de Machaut, Joni Mitchell or any other composer he takes on: with love, respect and an insatiable curiosity for new possibilities.” Bleckmann says of Kate Bush, "Her music has this thing that I love in art: you're instantly drawn into someone's universe without really knowing why but somehow understanding everything in your heart …I now realize that the way she layered sound, speech and music became a major influence for my live electronic looping aesthetic.” The 2019-2020 season marks the sixth year of the Jewish Museum and Bang on a Can’s partnership. -

Jazz & Blues Magazin Mai/Juni Nr

Das Schweizer Jazz & Blues Magazin Mai/Juni Nr. 3 /2020 TS Schweiz CHF 11.00 / Deutschland / Österreich € 6,90 ' roo N ES' BLU JAZZ‘N 'MORE BEN WENDEL MARIA SCHNEIDER NILS WOGRAM ANNA & STOFFNER REVEREND SHAWN AMOS JANA HERZEN FEIGENWINTER/ OESTER/PFAMMATTER ELIAN ZEITEL DomINIK SCHÜRMANN REBECCA SAUNDERS ANDY GUHL ADRIAN MEARS LINDSAY BEAVER LEROY WILLIAMS LARISSA BAUMANN JAZZFESTIVAL SCHAFFHAUSEN CHRISTIAN MCBRIDE THE MOVEMENT REVISITED MIT MEHR ALS 100 CD-BESPRECHUNGEN JNM_03_20_01_Cover_Christian Mc Bride_def.indd 1 26.04.20 18:55 Situationsbedingt IM LIVE-ONLINE FORMAT Aktuelle Infos und Zugang: www.jazzfestival.ch JNM_03_20_02-03_EDI_Inhalt.indd 2 331. 1 . S c h aSchaffhauser f f h a u s e r J a z z f e s t i v a l Jazzfestival 113. 3 . b i s 1bis 6 . M a i 16.2 0 2 0 Mai 2020 wwww.jazzfestival.ch w w . j a z z f e s t i v a l . c h HIERRY BURGHERR T FOTO: Gestaltung: Rosmarie Tissi 26.04.20 19:57 EDITORIAL INHALT 3 Editorial/Inhalt/Impressum 4 Flashes 8 reviews Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, 10 PREVIEWS 12 Schaffhauser Jazzfestival Online-Edition in der letzten Ausgabe habe ich angekündigt, kürzertreten zu 14 Christian MCBriDE – wollen und das Editorial abzugeben. Dass ich nun aus aktuel- Die Diskriminierung existiert weiter lem Anlass doch wieder in die Tasten haue, ist in Anbetracht 17 Anna&Stoffner der Situation und für mich als Herausgeber von JAZZ’N’MORE 18 BEN Wendel eine Verpflichtung. 21 ADRIAN MearS 22 NilS WOGRAM Das Virus hat uns alle im Griff, wir mussten uns in no time 24 Maria Schneider auf ganz neue Lebensgewohnheiten einstellen und jeden 27 Feigenwinter/Oester/Pfammatter trifft es auf seine Weise. -

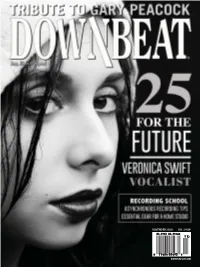

Downbeat.Com November 2020 U.K. £4.99

NOVEMBER 2020 U.K. £4.99 DOWNBEAT.COM november 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Musical Meet-Up Nist Dan Tepfer

CLASS NOTES 1997 Shane Endsley (see ’99). CHANCE ENCOUNTERS 1999 Ben Wendel has released a recording, Small Constructions (Sunnyside Records), with pia- Musical Meet-Up nist Dan Tepfer. In addition, the Boston-area alumni find each other while working (and playing) quintet Kneebody, which includes Wendel, Adam Benjamin, Shane together in the Cambridge Symphony Orchestra. Endsley ’97, and Kaveh Rastegar ’01, has released its fourth CD, The If you’ve moved away from Line (Concord Records). Rochester and live in a sizeable metro area, maybe you’ve met and 2001 Kaveh Rastegar (see ’99). even befriended a fellow Rochester alumnus or two. Someone you never 2003 Composer and trumpet- knew as a student. Someone who er Andre Canniere (MM) has may have attended many years released his second solo CD, Co- before or after you did. alescence (Whirlwind Record- ings). He’s based in London. That’s the kind of chance en- counter that happened to Lydia 2008 Shauli Einav (MM) re- Beall ’02, Abe Dewing ’93, and Kim leased two recordings in 2013: Etingoff ’10. Living in the Boston Generations (Posi-Tone Records) area, they met as members of the and The Truth About Me (Cristal all-volunteer Cambridge Symphony Records). After seven years in Orchestra. New York City, Shauli has moved YELLOWJACKET STRINGS ATTACHED: Living and working in Abe, who oversees digital adver- to Paris. Ailbhe McDonagh the Boston area, alumni Dewing, Beall, and Etingoff (left tising for the Boston Herald, joined (MM) has released a CD, It’s to right) met while playing in the all-volunteer Cambridge the orchestra in 1994. -

BIO KNEEBODY Kneebody's Sound Is Explosive Rock Energy Paralleled

BIO KNEEBODY Kneebody’s sound is explosive rock energy paralleled with high-level nuanced chamber ensemble playing, with highly wrought compositions that are balanced with adventurous no-holds-barred improvising. All “sounds-like” references can be set aside; this band has created a genre and style all its own. Kneebody is keyboardist Adam Benjamin, trumpeter Shane Endsley, saxophonist Ben Wendel and drummer Nate Wood. The band has no leader or rather, each member is the leader; they’ve developed their own musical language, inventing a unique cueing system that allows them each to change the tempo, key, style, and more in an instant. The quintet met in their late teens while at The Eastman School of Music and Cal Arts, became fast friends, and converged together as Kneebody amid the vibrant and eclectic music scene of Los Angeles in 2001. Since then, each band member has amassed an impressive list of credits and accomplishments over the years all while the band has continued to thrive and grow in reputation, solidifying a fan base around the world. “We are a democratic, equally owned-and-operated band with shared leadership,” says Shane Endsley. “Everyone brings in music and everyone votes on everything”. Kneebody draws upon influences spanning D’Angelo’s Voodoo to music by Elliot Smith, Bill Frisell, and Miles Davis. Their live shows are known for intense sonic landscapes of the Radiohead ilk, for the rhythmic bombast of a Squarepusher or Queens of the Stone Age show, and the harmonic depth and improvisational freedom experienced at a Brad Mehldau concert. In 2005, Kneebody released their debut self-titled album Kneebody on Dave Douglas’ Greenleaf Music Label. -

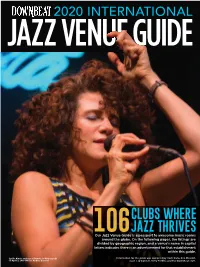

2020 International

2020 INTERNATIONAL Our Jazz Venue Guide is a passport to awesome music rooms around the globe. On the following pages, the listings are divided by geographic region, and a venue’s name in capital letters indicates there is an advertisement for that establishment within this guide. Cyrille Aimée onstage at Dakota in Minneapolis Information for the guide was compiled by Yoshi Kato, Ken Micallef, on April 3, 2019 (Photo: Andrea Canter) Sean J. O’Connell, Terry PerkinsFEBRUARY and 2020 the DOWNBEAT DownBeat 41 staff. UNITED STATES Smoke, a jazz club in New York City NEW YORK SMOKE 55 Bar New York, NY This beloved bar has hosted some of the city’s most innovative players, from Wayne Krantz and Zach Danziger to Mike Stern and Nate Wood. Jazz is heard here two or three nights a week, with blues and funk rounding out the schedule. This popular Greenwich Village haven fills up fast, so come early. 55bar.com Birdland New York, NY The original Birdland dominated 52nd Street in the ’40s, moved to the Upper West Side in the ’90s, and today is firmly planted in Manhattan’s theater district, not far from Times Square. Then as now, some of the finest jazz players in the world can be heard in this spacious club. Performers in January include Kurt Elling, Stacey Kent and John Pizzarelli with Jessica Molaskey. birdlandjazz.com Blue Note Bergonzi Quartet frequently perform at this New York, NY EAST Inman Square venue. The Blue Note packs them in every night of lilypadinman.com the week, and avid jazz fans often have the CONNECTICUT opportunity to speak to the musicians after Regattabar the set.