Risk and Resilience Assessment Niger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

32 Mohamadou Tchinta

1 LASDEL Laboratoire d’études et recherches sur les dynamiques sociales et le développement local _________ BP 12901, Niamey, Niger – tél. (227) 72 37 80 BP 1383, Parakou, Bénin – tél. (229) 61 16 58 Observatoire de la décentralisation au Niger (enquête de référence 2004) Les pouvoirs locaux dans la commune de Tchintabaraden Abdoulaye Mohamadou Enquêteurs : Afélane Alfarouk et Ahmoudou Rhissa février 05 Etudes et Travaux n° 32 Financement FICOD (KfW) 2 Sommaire Introduction 3 Les Kel Dinnig : de la confédération aux communes 3 Objectifs de l’étude et méthodologie 4 1. Le pouvoir local et ses acteurs 6 1.1. Histoire administrative de l’arrondissement et naissance d’un centre urbain 6 1.2. Les acteurs de l’arène politique locale 7 2. Le découpage de l’arrondissement de Tchintabaraden 19 2.1. Logiques territoriale et logiques sociales 19 2.2. Le choix des bureaux de vote 22 2.3. Les stratégies des partis politiques pour le choix des conseillers 23 2.4. La décentralisation vue par les acteurs 23 3. L’organisation actuelle des finances locales 25 3.1. Les projets de développement 25 3. 2. Le budget de l’arrondissement 26 Conclusion 33 3 Introduction Les Kel Dinnig : de la confédération aux communes L’arrondisssement de Tchintabaraden correspondait avant la création de celui d’Abalak en 1992 à l’espace géographique et social des Touareg Iwillimenden ou Kel Dinnig. Après la révolte de Kaocen en 1916-1917 et son anéantissement par les troupes coloniales françaises, l’aménokalat des Iwilimenden fut disloqué et réparti en plusieurs groupements. Cette technique de diviser pour mieux régner, largement utilisée par l’administration coloniale, constitue le point de départ du découpage administratif pour les populations de cette région. -

Dynamique Des Conflits Et Médias Au Niger Et À Tahoua Revue De La Littérature

Dynamique des Conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua Revue de la littérature Décembre 2013 Charline Burton Rebecca Justus Contacts: Charline Burton Moutari Aboubacar Spécialiste Conception, Suivi et Coordonnateur National des Evaluation – Afrique de l’Ouest Programmes - Niger Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire [email protected] + 227 9649 00 39 [email protected] +225 44 47 24 57 +227 90 60 54 96 Dynamique des conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua | PAGE 2 Table des matières 1. Résumé exécutif ...................................................................................................... 4 Contexte ................................................................................................. 4 Objectifs et méthodologie ........................................................................ 4 Résultats principaux ............................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Contexte de la revue de littérature ............................................................... 7 2.2 Méthodologie et questions de recherche ....................................................... 7 3. Contexte général du Niger .................................................................................. 10 3.1 Démographie ............................................................................................. 10 3.2 Situation géographique et géostratégique ............................................ -

In Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger Situation Overview : Niger – Tillabéri and Tahoua Regions | March 2020

Humanitarian situation monitoring (HSM) in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger Situation overview : Niger – Tillabéri and Tahoua regions | March 2020 Context Since the outbreak of violence in Mali in 2012, the border area between Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso has been characterized by a climate of insecurity due to the presence of armed groups, crime and rising tensions between communities1. The security situation in Niger has deteriorated sharply since 2018 and has caused the internal displacement of 159,028 people in the Tillabéri and Tahoua regions as of March 20202. In addition, the provision of humanitarian assistance is subject to multiple constraints resulting in limitations to access affected populations due to security, geographic and climatic factors, as well as to measures taken as part of the state of emergency covering parts of the Tillabéri and Tahoua regions1. Limited humanitarian access is one of the factors at the origin of important information gaps about the scope, nature and severity of needs. To fill these information gaps, REACH has been implementing a monitoring of the humanitarian situation, financed by the U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) since January 2020, following a pilot phase in November 20193. This situation overview presents the main results for data collected in March 2020 in the Tillabéri and Tahoua regions and analyzes the development of main indicators in the Tillabéri region between November 2019 and March 20204. Methodology This assessment adopts a so-called “Area of knowledge” methodology. The aim of this methodology is to collect, analyze and share up-to-date information regarding multi-sectoral humanitarian needs in the region, including in areas that are difficult to access. -

UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR Database

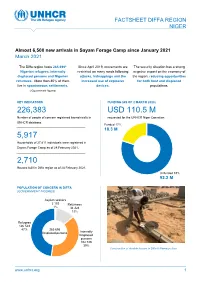

FACTSHEET DIFFA REGION NIGER Almost 6,500 new arrivals in Sayam Forage Camp since January 2021 March 2021 NNNovember The Diffa region hosts 265,696* Since April 2019, movements are The security situation has a strong Nigerian refugees, internally restricted on many roads following negative impact on the economy of displaced persons and Nigerien attacks, kidnappings and the the region, reducing opportunities returnees. More than 80% of them increased use of explosive for both host and displaced live in spontaneous settlements. devices. populations. (*Government figures) KEY INDICATORS FUNDING (AS OF 2 MARCH 2020) 226,383 USD 110.5 M Number of people of concern registered biometrically in requested for the UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR database. Funded 17% 18.3 M 5,917 Households of 27,811 individuals were registered in Sayam Forage Camp as of 28 February 2021. 2,710 Houses built in Diffa region as of 28 February 2021. Unfunded 83% 92.2 M the UNHCR Niger Operation POPULATION OF CONCERN IN DIFFA (GOVERNMENT FIGURES) Asylum seekers 2 103 Returnees 1% 34 324 13% Refugees 126 543 47% 265 696 Displaced persons Internally Displaced persons 102 726 39% Construction of durable houses in Diffa © Ramatou Issa www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Niger - Diffa / March 2021 Operation Strategy The key pillars of the UNHCR strategy for the Diffa region are: ■ Ensure institutional resilience through capacity development and support to the authorities (locally elected and administrative authorities) in the framework of the Niger decentralisation process. ■ Strengthen the out of camp policy around the urbanisation program through sustainable interventions and dynamic partnerships including with the World Bank. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the Use of Cerf Funds Niger Rapid Response Conflict-Related Displacement

RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS NIGER RAPID RESPONSE CONFLICT-RELATED DISPLACEMENT RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Mr. Fodé Ndiaye REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. Since the implementation of the response started, OCHA has regularly asked partners to update a matrix related to the state of implementation of activities, as well as geographical location of activities. On February 26, CERF-focal points from all agencies concerned met to kick off the reporting process and establish a framework. This was followed up by submission of individual projects and input in the following weeks, as well as consolidation and consultation in terms of the draft for the report. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES NO c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES NO The CERF Report has been shared with Cluster Coordinator and recipient agencies. 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT TABLE 1: EMERGENCY ALLOCATION OVERVIEW (US$) Total amount required for the humanitarian response: 53,047,888 Source Amount CERF 5,181,281 Breakdown -

5,500 New Arrivals in Sayam Forage Camp 225,118 5,538 1,972 USD 32

FACTSHEET DIFFA REGION 5,500 new arrivals in Sayam Forage Camp October 2020 The Diffa region hosts 265,696* Since April 2019, movements are The security situation has a strong Nigerian refugees, internally restricted on many roads following negative impact on the economy of displaced persons and Nigerien attacks, kidnappings and the the region, reducing opportunities returnees. More than 80% of them increased use of explosive for both host and displaced live in spontaneous settlements. devices. populations. (*Government figures) KEY INDICATORS FUNDING (AS OF 7 OCTOBER) 225,118 USD 32,14 million Number of people of concern registered biometrically in requested for the Nigeria situation in Niger UNHCR database. (Diffa and Maradi regions) Funded 5,538 38% 12,12 million Individuals were registered in Sayam Forage Camp these past three months following a secondary displacement 1,972 As of 31 September 2020, houses have been built in Unfunded Diffa region, 55% of the final target. 62% 20,01 million POPULATION OF CONCERN IN DIFFA (GOVERNMENT FIGURES) Asylum seekers 2 103 Returnees 1% 34 324 13% Refugees 126 543 47% Internally Displaced persons 102 726 39% www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Niger - Diffa / October 2020 Update on Achievements Operational Context Population movements and security situation The Diffa region has been hosting Nigerian refugees fleeing terrorist violence in the northern states of Nigeria since 2013. In the wake of the first attacks on Niger soil in 2015, the situation has dramatically deteriorated. In May 2015, the authorities decided to evacuate the population living in the Niger region of the Lake Chad Islands. -

NIGER : REGION DE TILLABERI Rapport Mensuel Au 31 Juillet 2020

NIGER : REGION DE TILLABERI Rapport mensuel Au 31 juillet 2020 Ce rapport est produit par OCHA Niger en collaboration avec les partenaires humanitaires. Il couvre la période du 1er au 31 juillet 2020. Le prochain rapport sera diffusé dans 30 jours. FAITS SAILLANTS Contexte sécuritaire o La situation sécuritaire est calme dans MALI l’ensemble, mais reste préoccupante Tahoua dans les zones frontalières avec le Mali BANIBANGOU et le Burkina Faso, où des mouvements ABALA AYOROU des Groupes Armés Non Etatiques BANKILARE FILINGUE (GANE) sont fréquemment signalés. OUALLAM TILLABERI Ceux-ci continuent de s’en prendre aux TERA populations civiles à travers des GOTHEYE BALEYARA demandes de paiement de la « dîme NIAMEY forcée » et enlèvements des personnes KOLLO TORODI DOSSO et de leurs biens. SAY o Les opérations militaires ont fortement Dosso contribué à faire baisser les attaques BURKINA FASO Fleuve Niger des positions des forces de défense et de sécurité (FDS) par les éléments de NIGERIA BENIN GANE. Le changement de la tactique Les frontières et les noms indiqués et les désignations employées sur cette carte n'impliquent pas reconnaissance ou acceptation officielle par militaire aurait également contribué à l'Organisation des Nations Unies. cette accalmie. D’autres facteurs comme les conflits d’intérêts causant les affrontements directs entre les GANE, qui jadis s’unissaient pour lancer des attaques de grande envergure contre les positions militaires, sont à considérer. o Des opérations militaires conduites dans le département d’Abala-frontière Mali. o Les mouvements des populations se poursuivent, notamment le long des frontières du Mali et du Burkina Faso et à l’intérieur de la région en raison des violences et/ou menaces perpétrées par les GANE sur les populations et les opérations militaires. -

Threat Analysis

Threat analysis: West African giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis peralta) in Republic of Niger April 2020 Kateřina Gašparová1, Julian Fennessy2, Thomas Rabeil3 & Karolína Brandlová1 1Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Kamýcká 129, 165 00 Praha Suchdol, Czech Republic 2Giraffe Conservation Foundation, Windhoek, Namibia 3Wild Africa Conservation, Niamey, Niger Acknowledgements We would like to thank the Nigerien Wildlife Authorities for their valuable support and for the permission to undertake the work. Particularly, we would like to thank the wildlife authorities’ members and rangers. Importantly, we would like to thank IUCN-SOS and European Commission, Born Free Foundation, Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance, Sahara Conservation Fund, Rufford Small Grant, Czech University of Life Sciences and GCF for their valuable financial support to the programme. Overview The Sudanian savannah currently suffers increasing pressure connected with growing human population in sub-Saharan Africa. Human settlements and agricultural lands have negatively influenced the availability of resources for wild ungulates, especially with increased competition from growing numbers of livestock and local human exploitation. Subsequently, and in context of giraffe (Giraffa spp.), this has led to a significant decrease in population numbers and range across the region. Remaining giraffe populations are predominantly conserved in formal protected areas, many of which are still in the process of being restored and conservation management improving. The last population of West African giraffe (G. camelopardalis peralta), a subspecies of the Northern giraffe (G. camelopardalis) is only found in the Republic of Niger, predominantly in the central region of plateaus and Kouré and North Dallol Bosso, about 60 km south east of the capital – Niamey, extending into Doutchi, Loga, Gaya, Fandou and Ouallam areas (see Figure 1). -

Niger: Frequently Asked Questions About the October 2017 Attack on U.S

Niger: Frequently Asked Questions About the October 2017 Attack on U.S. Soldiers Alexis Arieff, Coordinator Specialist in African Affairs Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs Andrew Feickert Specialist in Military Ground Forces Kathleen J. McInnis Analyst in International Security John W. Rollins Specialist in Terrorism and National Security Matthew C. Weed Specialist in Foreign Policy Legislation October 27, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44995 Niger: Frequently Asked Questions About the October 2017 Attack on U.S. Soldiers Summary A deadly attack on U.S. soldiers in Niger and their local counterparts on October 4, 2017, has prompted many questions from Members of Congress about the incident. It has also highlighted a range of broader issues for Congress pertaining to oversight and authorization of U.S. military deployments, evolving U.S. global counterterrorism activities and strategy, interagency security assistance and cooperation efforts, and U.S. engagement with countries historically considered peripheral to core U.S. national security interests. This report provides background information in response to the following frequently asked questions: What is the security situation in Niger? How big is the U.S. military presence in Niger? For what purposes are U.S. military personnel in Niger, and what role has Congress played in the U.S. military presence there? Is the U.S. military presence in Niger related to the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF)? What is the state of U.S.-Niger relations and aid? Where else in Africa are U.S. military personnel deployed? Medical evacuation: What is the “golden hour” and does it apply to troop deployments in Africa? What are the broader implications of building partner capacity in Niger for DOD? Who were the four U.S. -

Overview of Key Livelihood Activities in Northern Niger

Research Paper November 2018 Overview of Key Livelihood Activities in Northern Niger Rida LYAMMOURI RP-18/08 1 2 Overview of Key Livelihood Activities in Northern Niger RIDA LYAMMOURI 3 About OCP Policy Center The OCP Policy Center is a Moroccan policy-oriented think tank based in Rabat, Morocco, striving to promote knowledge sharing and to contribute to an enriched reflection on key economic and international relations issues. By offering a southern perspective on major regional and global strategic challenges facing developing and emerging countries, the OCP Policy Center aims to provide a meaningful policy-making contribution through its four research programs: Agriculture, Environment and Food Security, Economic and Social Development, Commodity Economics and Finance, Geopolitics and International Relations. On this basis, we are actively engaged in public policy analysis and consultation while promoting international cooperation for the development of countries in the southern hemisphere. In this regard, the OCP Policy Center aims to be an incubator of ideas and a source of forward thinking for proposed actions on public policies within emerging economies, and more broadly for all stakeholders engaged in the national and regional growth and development process. For this purpose, the Think Tank relies on independent research and a solid network of internal and external leading research fellows. One of the objectives of the OCP Policy Center is to support and sustain the emergence of wider Atlantic Dialogues and cooperation on strategic regional and global issues. Aware that achieving these goals also require the development and improvement of Human capital, we are committed through our Policy School to effectively participate in strengthening national and continental capacities, and to enhance the understanding of topics from related research areas. -

(Between Warrior and Helplessness in the Valley of Azawaɤ ) Appendix 1: Northern Mali and Niger Tuareg Participation in Violenc

Appendix 1: Northern Mali and Niger Tuareg Participation in violence as perpetrators, victims, bystanders from November 2013 to August 2014 (Between Warrior and Helplessness in the Valley of Azawaɤ ) Northern Mali/Niger Tuareg participation in violence (perpetrators, victims, bystanders) November 2013 – August 2014. Summarized list of sample incidents from Northern Niger and Northern Mali from reporting tracking by US Military Advisory Team, Niger/Mali – Special Operations Command – Africa, USAFRICOM. Entries in Red indicate no Tuareg involvement; Entries in Blue indicate Tuareg involvement as victims and/or perpetrators. 28 November – Niger FAN arrests Beidari Moulid in Niamey for planning terror attacks in Niger. 28 November – MNLA organizes protest against Mali PMs Visit to Kidal; Mali army fires on protestors killing 1, injuring 5. 30 November – AQIM or related forces attack French forces in Menaka with Suicide bomber. 9 December – AQIM and French forces clash in Asler, with 19 casualties. 14 December – AQIM or related forces employ VBIED against UN and Mali forces in Kidal with 3 casualties. 14 December – MUJWA/AQIM assault a Tuareg encampment with 2 casualties in Tarandallet. 13 January – AQIM or related forces kidnap MNLA political leader in Tessalit. 16 January – AQIM kidnap/executes MNLA officer in Abeibera. 17 January – AQIM or related forces plant explosive device near Christian school and church in Gao; UN forces found/deactivated device. 20 January – AQIM or related forces attacks UN forces with IED in Kidal, 5 WIA. 22 January – AQIM clashes with French Army forces in Timbuktu with 11 Jihadist casualties. 24 January – AQIM or related forces fires two rockets at city of Kidal with no casualties.