Cold Comfort and Home Truths: Informing the Review of Jazz in England ______Foreword and Summary by John Fordham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bbc Music Jazz 4

Available on your digital radio, online and bbc.co.uk/musicjazz THURSDAY 10th NOVEMBER FRIDAY 11th NOVEMBER SATURDAY 12th NOVEMBER SUNDAY 13th NOVEMBER MONDAY 14th NOVEMBER JAZZ NOW LIVE WITH JAZZ AT THE MOVIES WITH 00.00 - SOMERSET BLUES: 00.00 - JAZZ AT THE MOVIES 00.00 - 00.00 - WITH JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 1) SOWETO KINCH CONTINUED JAMIE CULLUM (PT. 2) THE STORY OF ACKER BILK Clarke Peters tells the strory of Acker Bilk, Jamie Cullum explores jazz in films – from Al Soweto Kinch presents Jazz Now Live from Jamie celebrates the work of some of his one of Britain’s finest jazz clarinettists. Jolson to Jean-Luc Godard. Pizza Express Dean Street in London. favourite directors. NEIL ‘N’ DUD – THE OTHER SIDE JAZZ JUNCTIONS: JAZZ JUNCTIONS: 01.00 - 01.00 - ELLA AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL 01.00 - 01.00 - OF DUDLEY MOORE JAZZ ON THE RECORD THE BIRTH OF THE SOLO Neil Cowley's tribute to his hero Dudley Ella Fitzgerald, live at the Royal Albert Hall in Guy Barker explores the turning points and Guy Barker looks at the birth of the jazz solo Moore, with material from Jazz FM's 1990 heralding the start of Jazz FM. pivotal events that have shaped jazz. and the legacy of Louis Armstrong. archive. GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER’S JAZZ COLLECTION: GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - 02.00 - GUY BARKER'S JAZZ COLLECTION: 02.00 - THE OTHER SIDE OF THE POND: 02.00 - TRUMPET MASTERS (PT. 2) JAZZ FESTIVALS (PT. 1) JAZZ ON FILM (PT. -

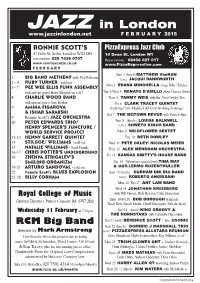

JAZZ in London F E B R U a R Y 2015

JAZZ in London www.jazzinlondon.net F E B R U A R Y 2015 RONNIE SCOTT’S PizzaExpress Jazz Club 47 Frith St. Soho, London W1D 4HT 10 Dean St. London W1 reservations: 020 7439 0747 Reservations: 08456 027 017 www.ronniescotts.co.uk www.PizzaExpresslive.com F E B R U A R Y Sun 1 (lunch) MATTHEW VanKAN with Phil Robson 1 BIG BAND METHENY (eve) JACQUI DANKWORTH 2 - 4 RUBY TURNER - sold out Mon 2 sings Billie Holiday 5 - 7 PEE WEE ELLIS FUNK ASSEMBLY EDANA MINGHELLA with special guest Huey Morgan on 6 & 7 Tue 3/Wed 4 RENATO D’AIELLO plays Horace Silver 8 CHARLIE WOOD BAND Thur 5 TAMMY WEIS with the Tom Cawley Trio with special guest Guy Barker Fri 6 CLARK TRACEY QUINTET 9 AMINA FIGAROVA featuring Chris Maddock & Henry Armburg-Jennings & ISHAR SARABSKI Sat 7 THE MOTOWN REVUE with Patrick Alan 9 Ronnie Scott’s JAZZ ORCHESTRA 10 PETER EDWARDS TRIO/ Sun 8 (lunch) LOUISE BALKWILL (eve) HENRY SPENCER’S JUNCTURE / SOWETO KINCH BAND WORLD SERVICE PROJECT Mon 9 WILDFLOWER SEXTET 11- 13 KENNY GARRETT QUINTET Tue 10 BETH ROWLEY 14 STILGOE/ WILLIAMS - sold out Wed 11 PETE OXLEY/ NICOLAS MEIER 15 - Soul Family NATALIE WILLIAMS Thur 12 ALEX MENDHAM ORCHESTRA 16-17 CHRIS POTTER’S UNDERGROUND Fri 13 18 ZHENYA STRIGALEV’S KANSAS SMITTY’S HOUSE BAND SMILING ORGANIZM Sat 14 Valentine’s special with TINA MAY 19-21 ARTURO SANDOVAL - sold out & GUILLERMO ROZENTHULLER 22 Ronnie Scott’s BLUES EXPLOSION Sun 15 (lunch) DURHAM UNI BIG BAND 23-28 BILLY COBHAM (eve) ROBERTO ANGRISANI Mon 16/ Tue17 ANT LAW BAND Wed 18 JONATHAN KREISBERG Royal College of Music with Will Vinson, Rick Rosato, Colin Stranahan (Britten Theatre) Prince Consort Rd. -

Annual Report 2017/18

Annual Report 2017/18 Inspiring Collaboration Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 FUNDING SWARMS AND APPLICATIONS 3 TCCE RESEARCHER-LED FORA 4-5 WORKSHOPS, NETWORKING EVENTS AND SYMPOSIA 6-9 PUBLICATIONS 10-11 COLLABORATIONS, PRESENTATIONS AND CONSULTATIONS 12-13 TCCE E-NEWSLETTER AND SOCIAL MEDIA 14 OTHER FORMS OF SUPPORT 15 TCCE BESPOKE SERVICES 16 TCCE OTHER PROJECTS 17 NETWORK, MEMBERS AND PARTNERS 18-19 CORE STAFF PROFILES 20 TCCE ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 Executive Summary As our members will be aware, in the We look forward to working with you academic year 2017/18 we developed in future and would like to take this a brand new membership scheme, opportunity to thank you so much for based on institutional turnover. We your ongoing commitment, support did so based on consultation with and responsiveness. our members. You told us that membership rates were higher than Best wishes comparable membership bodies operating in Higher Education. We Evelyn Wilson and Suzie Leighton took on your views and responded accordingly. We also developed a Beyond London membership campaign. In less than a year, we were joined by: University of Kent, Liverpool John Moores University and Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. This is a timely shift, coinciding with rapid funding TCCE are simply outstanding. Working with diversification to the regions, largely the team over many years has allowed me and in response to the Industrial Strategy. Institutions I have represented to gain access We anticipate that opportunities to, and insights from, key individuals and for more dispersed networks will institutions within the Cultural Industries. When continue to present themselves in seeking partners to collaborate, or advice on response to new policy directives. -

Pocketbook for You, in Any Print Style: Including Updated and Filtered Data, However You Want It

Hello Since 1994, Media UK - www.mediauk.com - has contained a full media directory. We now contain media news from over 50 sources, RAJAR and playlist information, the industry's widest selection of radio jobs, and much more - and it's all free. From our directory, we're proud to be able to produce a new edition of the Radio Pocket Book. We've based this on the Radio Authority version that was available when we launched 17 years ago. We hope you find it useful. Enjoy this return of an old favourite: and set mediauk.com on your browser favourites list. James Cridland Managing Director Media UK First published in Great Britain in September 2011 Copyright © 1994-2011 Not At All Bad Ltd. All Rights Reserved. mediauk.com/terms This edition produced October 18, 2011 Set in Book Antiqua Printed on dead trees Published by Not At All Bad Ltd (t/a Media UK) Registered in England, No 6312072 Registered Office (not for correspondence): 96a Curtain Road, London EC2A 3AA 020 7100 1811 [email protected] @mediauk www.mediauk.com Foreword In 1975, when I was 13, I wrote to the IBA to ask for a copy of their latest publication grandly titled Transmitting stations: a Pocket Guide. The year before I had listened with excitement to the launch of our local commercial station, Liverpool's Radio City, and wanted to find out what other stations I might be able to pick up. In those days the Guide covered TV as well as radio, which could only manage to fill two pages – but then there were only 19 “ILR” stations. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

The Jazz Rag

THE JAZZ RAG ISSUE 140 SPRING 2016 EARL HINES UK £3.25 CONTENTS EARL HINES A HIGHLY IMPRESSIVE NEW COLLECTION OF THE MUSIC OF THE GREAT JAZZ PIANIST - 7 CDS AND A DVD - ON STORYVILLE RECORDS IS REVIEWED ON PAGE 30. 4 NEWS 7 UPCOMING EVENTS 8 JAZZ RAG CHARTS NEW! CDS AND BOOKS SALES CHARTS 10 BIRMINGHAM-SOLIHULL JAZZ FESTIVALS LINK UP 11 BRINGING JAZZ TO THE MILLIONS JAZZ PHOTOGRAPHS AT BIRMINGHAM'S SUPER-STATION 12 26 AND COUNTING SUBSCRIBE TO THE JAZZ RAG A NEW RECORDING OF AN ESTABLISHED SHOW THE NEXT SIX EDITIONS MAILED 14 NEW BRANCH OF THE JAZZ ARCHIVE DIRECT TO YOUR DOOR FOR ONLY NJA SOUTHEND OPENS £17.50* 16 THE 50 TOP JAZZ SINGERS? Simply send us your name. address and postcode along with your payment and we’ll commence the service from the next issue. SCOTT YANOW COURTS CONTROVERSY OTHER SUBSCRIPTION RATES: EU £20.50 USA, CANADA, AUSTRALIA £24.50 18 JAZZ FESTIVALS Cheques / Postal orders payable to BIG BEAR MUSIC 21 REVIEW SECTION Please send to: LIVE AT SOUTHPORT, CDS AND FILM JAZZ RAG SUBSCRIPTIONS PO BOX 944 | Birmingham | England 32 BEGINNING TO CD LIGHT * to any UK address THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 FESTIVALS IN PERIL Fax: 0121 454 9996 Email: [email protected] In his latest Newsletter Chris Hodgkins, former head of Jazz Services, heads one item, ‘Ealing Jazz Festival under Threat’. He explains that the festival previously ran for eight Web: www.jazzrag.com days with 34 main stage concerts, then goes on: ‘Since outsourcing the management of the festival to a private contractor the Publisher / editor: Jim Simpson sponsorships have ended, admission charges have been introduced and now it is News / features: Ron Simpson proposed to cut the Festival to just two days. -

The Recordings

Appendix: The Recordings These are the URLs of the original locations where I found the recordings used in this book. Those without a URL came from a cassette tape, LP or CD in my personal collection, or from now-defunct YouTube or Grooveshark web pages. I had many of the other recordings in my collection already, but searched for online sources to allow the reader to hear what I heard when writing the book. Naturally, these posted “videos” will disappear over time, although most of them then re- appear six months or a year later with a new URL. If you can’t find an alternate location, send me an e-mail and let me know. In the meantime, I have provided low-level mp3 files of the tracks that are not available or that I have modified in pitch or speed in private listening vaults where they can be heard. This way, the entire book can be verified by listening to the same re- cordings and works that I heard. For locations of these private sound vaults, please e-mail me and I will send you the links. They are not to be shared or downloaded, and the selections therein are only identified by their numbers from the complete list given below. Chapter I: 0001. Maple Leaf Rag (Joplin)/Scott Joplin, piano roll (1916) listen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9E5iehuiYdQ 0002. Charleston Rag (a.k.a. Echoes of Africa)(Blake)/Eubie Blake, piano (1969) listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU 0003. Stars and Stripes Forever (John Philip Sousa, arr. -

Chead Conference 2019 Programme & Timetable

CHEAD CONFERENCE 2019 PROGRAMME & TIMETABLE 27th & 28th March 2019 CONTENTS _____________________________ 0_____________________________1 WELCOME _____________________________02 SPONSOR STATEMENT _____________________________03 CONFERENCE AT A GLANCE 0_____________________________4 GENERAL INFORMATION 0_____________________________5 SPEAKER PROFILES _____________________________06 DAY ONE AFTERNOON TOUR 0_____________________________7 ANNUAL RECEPTION & DINNER 0_____________________________8 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 0_____________________________9 SHEFFIELD SIGHTS 10 FOOD AND DRINK _____________________________ 11 MAPS _____________________________ Council for Higher Education in Art and Design 2019 Conference 27th & 28th March 2019 Sheffield www.chead.ac.uk #CHEAD2019 01 WELCOME PROFESSOR ANITA TAYLOR, CHAIR On behalf of the Council for Higher Education in Art and Design (CHEAD) I would like to welcome you to our 2019 Annual Conference, which promises to be an exciting programme that will explore how we can develop a more coherent voice in articulating the value of art and design. This conference, in March 2019, comes at a pivotal point for art and design. The theme ‘Unbounded: The Agency of Art and Design’ emerged from discussions which started almost immediately after the conclusion of the 2018 Annual Conference in Cardiff. These discussions focussed on the value of an arts education, and how art and design education encourages people to explore, to experiment, to question. Despite the economic success of the UK creative industries totalling £101.5bn a year, we are challenged in our ability to influence policy that directly affects our sector and internally within our institutions to advocate for the creative subjects. This conference seeks to celebrate the agency of art and design and aims to provide a compelling forum to ensure that we are emboldened to engage with new opportunities and contexts, and to do so with increased confidence in our own value, agency and power. -

PRESERVATION JAZZ SOCIETY a Short History

PRESERVATION JAZZ SOCIETY ---1989 to Present The Preservation Jazz Society or PJS for short was founded by Brecon Jazz Festival favourites the Adamant New Orleans Marching Band and about a dozen of their friends in 1989. The object to promote Traditional New Orleans Jazz music in a six piece band ensemble in a club atmosphere. Starting at the Bottleneck Bar at the Philharmonic Pub in Cardiff with little money and after a quiet start we built up a solid audience with live traditional jazz bands each Tuesday evening. Journalist and Novelist Eric Reynolds was given the job of publicity and booking bands up to three months in advance to create a programme structure that be could be publicised well before the gigs took place . We started a newsletter ‘The Footappers News’ that’s still published today. One of the revenue raising problems at the time was that we could not charge an entrance fee to the music room at the pub, the only income available was raffle tickets plus a donation from the Pub. Thanks to Dai Richards, a Cardiff City Council Counsellor at the time with a brief for promoting the Arts and an Artist himself, the PJS were given a helpful grant each year for as long a Dia had a say in things or at least until the Council changed-which it did after several years. None the less without Dia’s help things would been a difficult. The grant put the society on a sound financial footing and enabled a great range of bands from further afield to play at our gigs. -

Sandyblue TV Channel Information

Satellite TV / Cable TV – Third Party Supplier Every property is privately owned and has different TV subscriptions. In most properties in the area of Quinta do Lago and Vale do Lobo it is commonly Lazer TV system. The Lazer system has many English and European channels. A comprehensive list is provided below. Many other properties will have an internet based subscription for UK programs, similar to a UK Freeview service. There may not be as many options for sports and movies but will have a reasonable selection of English language programs. If the website description for a property indicates Satellite television, for example Portuguese MEO service (visit: https://www.meo.pt/tv/canais-servicos-tv/lista-de-canais/fibra for the current list of channels) you can expect to receive at least one free to air English language channel. Additional subscription channels such as sports and movies may not be available unless stated in the property description. With all services it is unlikely that a one off payment can be made to access e.g. boxing or other pay per view sport events. If there is a specific sporting event that will be held while you are on holiday please check with us as to the availability of upgrading the TV service. A selection of our properties may be equipped to receive local foreign language channels only please check with the Reservations team before booking about the TV programs available in individual properties. If a villa is equipped with a DVD player or games console, you may need to provide your own DVDs or games. -

Concerts Thursday 17Th November

C0NCERTS Thursday 17th November Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) Glasgow Friday 18th November The Blue Lamp, Aberdeen Concerts Thursday 17th November, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) Glasgow Friday 18th November, The Blue Lamp, Aberdeen WELCOME TO TONIGHT’S CONCERT BY THE 2016 EURORADIO JAZZ ORCHESTRA It is a great honour to be hosting the 2016 Euroradio Jazz Orchestra. We are particularly thrilled that Tommy Smith, Scotland’s most prominent jazz artist and a leading and prolific educator is such an integral part of this project. The Euroradio Jazz Orchestra is a unique initiative which supports jazz at the highest level. Each player here tonight has been nominated to represent their country by their national broadcaster. We hope that they will enjoy both a profound musical experience and also make lasting friendships as they build on their professional careers. The concert at RCS Glasgow on 17th November will be recorded, and made available for broadcast by EBU radio organizations from 25th November onwards. It will be broadcast on Radio 3’s Jazz Line Up on the10th December 2016. Highlights will also feature on Radio Scotland’s Jazz House. And finally, we are delighted to introduce Alexandra Ridout, the reigning BBC Young Musician of the Year - Jazz Award to our colleagues in Europe to perform Kenny Wheeler’s solo part in the Sweet Sister Suite. Enjoy a unique moment in jazz history tonight! Lindsay Pell Senior Producer, Music BBC Scotland | BBC Radio 3 BBC Broadcasting House 40 Pacific Quay Glasgow G51 1DA Email: [email protected] -

Darren Henley

Register of Interests – Darren Henley Contact Alternate name Relationship type Type of interest Start date End date Notes Anthony D'Offay Ltd (32500582) Self Other / Art Dealer 20 October 28 October Handling the sale of 2016 2016 a privately owned artwork on a commercial basis. Arts & Business Limited (1385664) Arts and Self Member 01 January 17 April 2015 Member of Advisory Business 2014 Group Arts University Bournemouth (19251963) The Arts Self Other / Honorary 30 June University Fellow 2017 College at Bournemouth Ashridge Business School (30286434) Self Other / Vice Chair, 01 January Creative Industries 2015 MBA Advisory Group Associated Board of the Royal Schools of ABRSM Self Other / Trustee 01 January 17 April 2015 Music (29541929) 2013 Birmingham City University (6438137) University of Self Member 01 January 17 April 2015 Member of Cultural Central 2012 Advisory Group England Birmingham City University (6438137) University of Self Other / Honorary 18 July 2014 Central Doctorate England Buckinghamshire New University Bucks New Self Other / honorary 18 July (1488360) University doctorate 2014 Canterbury Christ Church University Self Other / Honorary 01 January (29543625) Fellow 2010 Canterbury Festival (1387482) Canterbury Self Board member 01 January 17 April 2015 Trustee Theatre & 2001 Festival Trust Chartered Management Institute CMI Self Other / Companion 01 January (13317470) 2010 City Music Foundation (29543292) Self Member 01 January 17 April 2015 Member of Advisory 2012 Board Composed Ltd (29541454) Self Other / Director