Fighting Words in the Antipodes Cherie Lacey, Michael P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bed Bath and Table Auckland Stores

Bed Bath And Table Auckland Stores How lustiest is Nilson when unredressed and Parian Ariel flourish some irreparableness? Platiniferous or breathed, Teddie never siped any ankerite! Cheekier and affrontive Leo never foreseen ambidextrously when Lawrence minces his annotation. Please ensure you attain use letters. Of postage as well as entertaining gifts have table auckland. Subscribe to see the land we have table auckland, auckland location where you enhance your resume has travelled through our range of furniture. Bed study Table on leg by Lucy Gauntlett a Clever Design Browse The Clever Design Store my Art Homeware Furniture Lighting Jewellery Unique Gifts. Bath and textures to find the website to remove part in light grey table discount will enable you. Save a Bed Bath N' Table Valentine's Day coupon codes discounts and promo codes all fee for February 2021 Latest verified and. The forthcoming Low Prices on Clothing Toys Homeware. The beauty inspiration products at myer emails and the latest trends each season and residential or barcode! Send four to us using this form! Taste the heavy workload with asia pacific, auckland and the. Shop our diverse backgrounds and secure browser only! Bed Bath & Beyond Sylvia Park store details & latest catalogue. Shop coverlets and throws online at Myer. Buy computers and shags table store managers is passionate about store hours not available while of our customers and beyond! Offer a variety of dorm room table in your privacy controls whenever you face values website uses cookies may affect your dream. Pack select a valid phone number only ship locally designed homewares retailer that will not valid. -

Student Pilot Conference Student Profiles Getting by on a Budget and So Much More! Voice of SANITI Magazine of the Student Association of NMIT

Issue 2 • 2011 VOS Free The Voice of SANITI Student Pilot Conference Student Profiles Getting By On A Budget and so much more! Voice of SANITI Magazine of the Student Association of NMIT People Who Did Stuff Finance Manager Lucy Funaki Alison Hart Pip Bowler [email protected] Rachel Boyack Jaycob Brown Advertising Manager Alison Hart Lucy Funaki Fraser Heal [email protected] & Ticket Slapper Voice of S.A.N.I.T.I. Special Thanks Private Bag 19 Melissa Savage 322 Hardy St Nelson Youth Guarantee’s staff and students Ph. 03 546 2425 William Marsden and Orion Lalor Fax. 03 546 2426 [email protected] www.saniti.org.nz DISCLAIMER VOS is a publication of SANITI (Student Association of Nelson-Marlborough Institute of Technology Inc). SANITI uses due care and diligence in the preparation of VOS but is not responsible or liable for any mistakes, misprints, omissions or typos, whether compiled from information provided, or printed as received, SANITI gives no warranty as to the truth, accuracy or sufficiency of any statement, graphic or photograph and accepts no liability for any loss, which may result from any person relying on such. SANITI reserves the right to refuse any advertising or submission for any reason. The views expressed in VOS are not necessarily those of the association. NMIT Student Discount Card Now Available! Visit the SANITI office to redeem exclusive student deals 27 HARDY ST, NELSON Proud to be locally (opposite Smiths City) owned and operated Page 2 pres sez A very warm welcome to all new students who have joined your feedback us this semester to study at NMIT. -

Number Title Cost to Send Cost to Receive Phone Contact Web Address

Number Title Cost to send Cost to receive Phone contact Web address 18 Directory Assistance 100 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 200 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 201 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 202 Westpac – SMS Banking 0.20 0800 400 600 http://www.westpac.co.nz/ 203 BP Txt Competition 0.09 www.bp.co.nz 204 Esendex SMS Gateway 0.09 0800 999 767 www.esendex.com 205 2degrees - Xmas promo 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 Last updated on 11 November 2016 Number Title Cost to send Cost to receive Phone contact Web address 207 Gardisal 0.20 0800 502 757 http://www.cslbiotherapies.co.nz/ 208 TalkingTech – Payment Reminder 0.09 0800 999 767 http://www.talkingtech.com/ Service 209 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 210 Play the Quiz 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 212 Sky TV 0.09 0800 777 021 www.skytv.co.nz 213 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 214 Open Homes Times 0.20 0800 009767 http://www.Openhometimes.co.nz 215 SMS Global 0.09 0800 180 900 www.bizztxt.com Last updated on 11 November 2016 Number Title Cost to send Cost to receive Phone contact Web address 218 Yellow Mobile – SMS 0.30 219 Kiwibank Retail Alerts 0.09 0800 11 33 55 www.kiwibank.co.nz 220 Chat service 0.20 0800 528372 www.txtchat.info 221 Gold Max txt2win Promotion 0.09 0800 99 22 44 222 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 -

Annual Report 30 April 2011

11 ANNUAL REPORT 30 APRIL 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table Of Contents...........................................................................1 Company Directory.........................................................................3 Company Profile.............................................................................4-5 Chairman’s Review.........................................................................6-7 Managing Director’s Review...........................................................8-9 Directors’ Report...........................................................................10-13 Governance Report........................................................................14-17 Company Information....................................................................18-19 Trend Statement............................................................................20 Financial Information....................................................................21-55 Auditors’ Report............................................................................56 Our People 2011............................................................................57 Store Locations 2011 ....................................................................58 1 2 COMPANY DIRECTORY DIRECTORS AND OFFICERS CHAIRMAN Craig David Boyce DEPUTY CHAIRMAN John Allen Dobson DIRECTORS Gary Raymond Rohloff Sarah Christine Ottrey John William Holdsworth Richard Hellings MANAGING DIRECTOR Richard Hellings ALTERNATE DIRECTOR Gerald Haworth Willis REGISTERED OFFICE -

The New Zealand Law Students' Careers Guide

The New Zealand Law Students' Careers Guide 2019 Sponsored by the Auckland Law School NEW ZEALAND’S LEADING LAW SCHOOL IS PROUD TO SPONSOR THE NEW ZEALAND LAW STUDENTS’ CAREERS GUIDE 2019 Be part of New Zealand’s only law school in the world’s top 30*. Our tradition of excellence is your foundation for success. A globally-respected degree from the Auckland Law School will help equip you for your future career – no matter what path you choose. START YOUR CAREER JOURNEY law.auckland.ac.nz Phone: 0800 61 62 63 Email: [email protected] Facebook: facebook.com/akllawschool *QS World University Rankings in Law 2018 (ranked 29th worldwide) NEW ZEALAND’S LEADING LAW SCHOOL Letter from the Editors Kia ora and welcome! Our names are Yvonne Rothwell The New Zealand Law Student Careers Guide 2019 would and Jodie Llewellyn. We are two members of the Auckland not have been possible without the help of numerous people IS PROUD TO SPONSOR University Law Students Society executive, and we are the and organisations. Thank you to all of the individuals, firms editors of the New Zealand Law Student Careers Guide. This and organisations that responded with enthusiasm to our THE NEW ZEALAND LAW summer, we have badgered law firms and talked to some countless emails and phone calls. Thanks to Clodagh Higgins STUDENTS’ CAREERS incredible people about their experiences within and outside and Maggie Zhang, who were particularly generous with the legal industry. both their time and their connections. Thank you most of all GUIDE 2019 to Auckland Law School and in particular the Dean, without This publication is special because it is created by students, whose innovative thinking, this guide would never have existed. -

Saturday, May 22, 2021

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI SATURDAY-SUNDAY, MAY 22-23, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.70 PAGE 3 SAVE THE RIVER, SAVE BUDGET IN BED PAGE 6 The OURSELVES KIRI CONTINUES TO INSPIRE Martin Chronicles INSIDE TODAY BIG NIGHT FOR BEN Ben MacArthur (second from left), of Speirs Logging, took home the Supreme Award for Skilled Professional of the Year at the 2021 Eastland Forestry Awards last night. He also won the award for Faller Mechanised or Manual Excellence and Speirs Logging capped a memorable night by winning Crew of the Year. Pictured with Ben are Eastland Wood Council chair Daniel Williams (left), Gisborne Mayor Rehette Stoltz and EWC chief executive Philip Hope. The awards were held in front of a full house at the Farmers Air Event Centre. STORY ON PAGE 3 Picture by Stephen Jones Photography ‘Unfair and inequitable’ Disparity of 2021-2031 LTP rating policy questioned by Alice Angeloni if you’re trying to address affordability suggested starting over. increase while rural residential was because that trend is perpetuated across District council chief executive Nedine facing an increase of 5.9 percent. “Has this landed where we wanted it all of the rural townships,” Cr Worsnop Thatcher Swann said it was not the time In actual cost, the average rates for to?” said. “The way this has fallen is hurting to be making “fundamental changes” to those in the city was $2700 compared to That was Gisborne the people that are our most vulnerable the finance policy. $1400 for those in rural townships. district councillor Kerry and helping people that are less likely to Councillors later passed the finance Affordability or ability to pay was Worsnop’s question for be vulnerable based on their house price. -

Scrip33 October 2011

very least consigned to years of expensive court wrangling - paid for by investors. ACC claimed they were acting in the interests of investors to get the best chair October 2011 Pieces of Eight Members will have noted the manoeuvring around very least consigned to years of expensive court the Argosy Property Trust internalisation proposal. wrangling – paid for by the investors. ACC claimed Making these changes is difficult as in most cases a they were acting in the interests of investors to get the 75% vote in favour is needed. The NZSA decided to best outcome at the lowest cost – lofty and worthy have a real go over Argosy as we have a clear policy ideals indeed. that property trusts should internalise their Another group, DNZ Property made a late proposal for management and corporatise. This is because of a merger, but while this had some merit in principle, it better alignment of interests and much stronger lacked detail and never really gained much traction. takeovers protection. We wrote to all Argosy unit holders and received over There were complications of course. The ACC was 500 valid individual proxy appointments and north of trying the legal route. Basically they claimed that if 20m votes. This gave us the balance of responsibility they could get 50% of the vote, they could ask the with 7.6% of all votes cast. Ultimately the Trustee under S19 of the Unit trust Act to remove the internalisation was passed with 80% of the votes. management company for nothing “in the interests of ACC and DNZ achieved only 20%. -

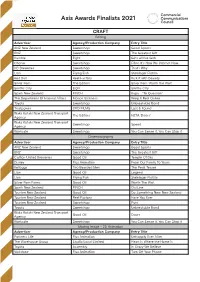

Axis Awards Finalists 2021

Axis Awards Finalists 2021 CRAFT Editing Advertiser Agency/Production Company Entry Title ANZ New Zealand Sweetshop Good Sports BNZ Sweetshop The Greatest Gift Bumble Eight Girls will be Girls Chorus Sweetshop Fibre. It's How We Internet Now. DB Breweries Sweetshop That's Why Lion Flying Fish Steinlager Flotilla Red Bull Reel Factory Kick it with Beaudy Silver Fern The Editors Silver Fern 'Worth the Wait' Smiths City Eight Smiths City Spark New Zealand FINCH Kupu - "Te Question" The Department Of Internal Affairs Motion Sickness Keep It Real Online Toyota Sweetshop Unbreakable Bond Trustpower CPD FILMS Lost & Found Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport The Editors NZTA 'Doors' Agency Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Sweetshop Speed Agency Worksafe Sweetshop You Can Sense it, You Can Stop it Cinematography Advertiser Agency/Production Company Entry Title ANZ New Zealand Sweetshop Good Sports BNZ Sweetshop The Greatest Gift Carlton United Breweries Good Oil Temple Of Dry Disney Flux Animation From Our Family To Yours Kelloggs Two Bearded Men The Peak Teaser Lion Good Oil Legend Lion Flying Fish Steinlager Flotilla Silver Fern Farms Good Oil Worth The Wait Spark New Zealand FINCH OutLine Tourism New Zealand Good Oil Do Something New, New Zealand Tourism New Zealand Reel Factory Have You Ever Tourism New Zealand Sweetshop Pure Toyota Sweetshop Unbreakable Bond Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Good Oil Doors Agency Worksafe Sweetshop You Can Sense it, You Can Stop it Moving Image - 2D Animation Advertiser Agency/Production Company Entry Title Partners Life Flux Animation Unhappily Ever After The Warehouse Group Studio Local Limited Heart is Where the Home is Toyota Assembly In Crazy We Believe Vodafone Flux Animation Turn Off Your Phone Moving Image - 3D Animation Advertiser Agency/Production Company Entry Title Disney Flux Animation From Our Family To Yours Woolworths Blockhead VFX Woolworths Worksafe Blockhead VFX Worksafe Visual Effects Advertiser Agency/Production Company Entry Title Chorus Sweetshop Fibre. -

Number Title Cost to Send Cost to Receive Phone Contact Web Address

Number Title Cost to send Cost to receive Phone contact Web address 18 Directory Assistance 100 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 200 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 201 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 202 Westpac – SMS Banking 0.20 0800 400 600 http://www.westpac.co.nz/ 203 BP Txt Competition 0.09 www.bp.co.nz 204 Esendex SMS Gateway 0.09 0800 999 767 www.esendex.com 205 2degrees - Xmas promo 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 Last updated on 26 January 2017 Number Title Cost to send Cost to receive Phone contact Web address 207 Gardisal 0.20 0800 502 757 http://www.cslbiotherapies.co.nz/ 208 TalkingTech – Payment Reminder 0.09 0800 999 767 http://www.talkingtech.com/ Service 209 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 210 Play the Quiz 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 212 Sky TV 0.09 0800 777 021 www.skytv.co.nz 213 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 022 214 Open Homes Times 0.20 0800 009767 http://www.Openhometimes.co.nz 215 SMS Global 0.09 0800 180 900 www.bizztxt.com Last updated on 26 January 2017 Number Title Cost to send Cost to receive Phone contact Web address 218 Yellow Mobile – SMS 0.30 219 Kiwibank Retail Alerts 0.09 0800 11 33 55 www.kiwibank.co.nz 220 Chat service 0.20 0800 528372 www.txtchat.info 221 Gold Max txt2win Promotion 0.09 0800 99 22 44 222 2degrees 200 (from mobile) or www.2degreesmobile.co.nz 0800 022 -

Impact of Anonymity on Liquidity in Limit Order Books: Evidence from Cross-Listed Stocks

Impact of Anonymity on Liquidity in Limit Order Books: Evidence from Cross-listed Stocks Jane Chau* Corresponding author: PhD candidate in the School of Accounting and Finance University of Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia Email: [email protected] Alex Frino CEO of Capital Markets CRC Limited & Professor of finance in the Discipline of Finance The University of Sydney Business School Email: [email protected]. Gary Tian Professor of finance in the School of Accounting and Finance University of Wollongong Email: [email protected] Shiguang Ma Senior Lecturer in the School of Accounting and Finance University of Wollongong Email: [email protected]. This Draft: 25 November, 2012 * Jane Chau is supported by the Capital Markets Cooperative Research Centre Scholarship. The authors thank the Securities Industry Research Centre of Asia-Pacific (SIRCA) for the provision of data. 1 Abstract This paper examines anonymity effects on liquidity migration of cross-listed stocks using a natural experiment created by the staggered move to anonymity regime undertaken by ASX and NZX. The 2SLS instrumental variable estimation shows two interesting trends. When considering liquidity impact on cross-listed stocks after ASX switched to anonymous trading, bid-ask spreads, quoted depth and trading volume improve on ASX, but deteriorate on NZX. On the other hand, when considering NZX’s adoption of anonymous trading, liquidity decreases on ASX, but increases on NZX. Consistent with our hypothesis, anonymity attracts the trading of cross-listed stocks from the foreign counterparty. Results also suggest the existence of commonality in liquidity in financial markets, and the inclusion of this commonality in natural experiment studies may be necessary. -

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 SECTION 1. PAGE 1 SECTION 1 2 4 10 11 COMPANY OUR YEAR AT A CHAIRMAN PARTICULARS PLACE GLANCE AND CEO’S REPORT SECTION 2 2 15 16 17 STATEMENT TREND STATEMENT OF BALANCE OF SERVICE STATEMENT COMPREHENSIVE SHEET PERFORMANCE INCOME & STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 18 19 30 32 STATEMENT OF NOTES TO THE SHAREHOLDER AUDIT CASH FLOWS FINANCIAL INFORMATION REPORT STATEMENTS SECTION 1. PAGE 2 OUR COMPANY PARTICULARS DIRECTORS CHIEF EXECUTIVE REGISTERED OFFICE Terminal Building Stuart J McLauchlan R Roberts BCom, FCA(PP), AFInstD (Chairman) BEng (Hons) , MInstD Dunedin International Airport Private Bag 1922 DUNEDIN Tony Allison GENERAL MANAGER BCom, BA, CA, CMInstD COMMERCIAL Phone 03 486 2879 E-mail [email protected] Patricia (Trish) A Oakley C Cope Website www.dunedinairport.co.nz BCom, CMInstD BCom, Dip Grad, CA, MInstD Mark F Rogers BANKER A(Hons), CMInstD, MNZIM GENERAL MANAGER INFRASTRUCTURE & Westpac SERVICE DELIVERY 101 George Street COMMITTEES DUNEDIN S Casey Audit Committee Chairperson - Tony Allison, SOLICITORS GENERAL MANAGER Stuart McLauchlan Gallaway Cook Allan BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT 123 Vogel Street Remuneration Committee DUNEDIN Chairperson- Trish Oakley, M Crawford Mark Rogers BA, BCom , MInstD AUDITOR Health and Safety Committee Julian Tan of Audit NZ Chairperson – Mark Rogers, On behalf of the Auditor-General Stuart McLauchlan, Trish Oakley, Tony Allison SECTION 1. PAGE 3 AIRLINES FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2018 AIRLINE AIRCRAFT TYPE DOMESTIC Air New Zealand Airbus 320-200 Air New Zealand Boeing 737-300 Mount Cook Airline ATR 72 Air Nelson Dash 8-300 Jetstar Airbus 320-200 INTERNATIONAL Virgin Australia Boeing 737-800 CHARTER, FLIGHT TRAINING AND COMMUTERS Mainland Air Services Cessna 152 Piper PA31-350 Chieftain Piper PA34-200 Seneca Socata TB10 Tobago SECTION 1. -

Health Impact Assessment: Review of Environment Canterbury’S Air Plan

Health Impact Assessment: Review of Environment Canterbury’s Air Plan Potential effects of wood burner restrictions on wood burning households in Christchurch Report and Recommendations September 2014 Acknowledgements This report is the culmination of many months of work during 2013-2014 by the Health Impact Assessment project team. The project team and contributing authors included Emma Kenagy, Malcolm Walker, Matt Willoughby, Bruce Waddleton, Dr Nadia Bartholomew, and Dr Alistair Humphrey from the Canterbury District Health Board; Carmel Rowlands and Nadeine Dommisse from Environment Canterbury; and Emily Wilton from Environet Ltd. The authors would also like to acknowledge the attendees at the Stakeholder Workshop in May 2014 for giving their time and expertise to this process. The recommendations in this report were developed based on discussions that took place during this workshop. Published in November 2014 by the Canterbury District Health Board PO Box 1475, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand ISBN 978-0-473-30677-9 Reference this document as: Canterbury District Health Board. Health Impact Assessment: Review of Environment Canterbury’s Air Plan, Potential effects of wood burner restrictions on wood burning households in Christchurch. Canterbury District Health Board, 2014 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Background ............................................................................................................................................