Priorities for Coral Reef Management in the Hawaiian Archipelago 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Keyword List Contains Indian Ocean Place Names of Coral Reefs, Islands, Bays and Other Geographic Features in a Hierarchical Structure

CoRIS Place Keyword Thesaurus by Ocean - 8/9/2016 Indian Ocean This keyword list contains Indian Ocean place names of coral reefs, islands, bays and other geographic features in a hierarchical structure. For example, the first name on the list - Bird Islet - is part of the Addu Atoll, which is in the Indian Ocean. The leading label - OCEAN BASIN - indicates this list is organized according to ocean, sea, and geographic names rather than country place names. The list is sorted alphabetically. The same names are available from “Place Keywords by Country/Territory - Indian Ocean” but sorted by country and territory name. Each place name is followed by a unique identifier enclosed in parentheses. The identifier is made up of the latitude and longitude in whole degrees of the place location, followed by a four digit number. The number is used to uniquely identify multiple places that are located at the same latitude and longitude. For example, the first place name “Bird Islet” has a unique identifier of “00S073E0013”. From that we see that Bird Islet is located at 00 degrees south (S) and 073 degrees east (E). It is place number 0013 at that latitude and longitude. (Note: some long lines wrapped, placing the unique identifier on the following line.) This is a reformatted version of a list that was obtained from ReefBase. OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bird Islet (00S073E0013) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bushy Islet (00S073E0014) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Fedu Island (00S073E0008) -

Range Expansion of the Whitenose Shark, Nasolamia Velox, and Migratory Movements to the Oceanic Revillagigedo Archipelago

Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, page 1 of 5. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2017 doi:10.1017/S0025315417000108 Range expansion of the whitenose shark, Nasolamia velox, and migratory movements to the oceanic Revillagigedo Archipelago (west Mexico) frida lara-lizardi1,2, mauricio hoyos-padilla2,3, james t. ketchum2,4 and felipe galva’ n-magan~a1 1Instituto Polite´cnico Nacional, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Av. IPN s/n. C.P. 23096. La Paz, B.C.S, Mexico, 2Pelagios-Kakunja´ A. C. 1540 Sinaloa, C.P. 23070, La Paz, B.C.S., Mexico, 3Fins Attached, 19675 Still Glen Way, Colorado Springs, CO 80908, USA, 4Centro de Investigaciones Biolo´gicas del Noroeste, Playa Palo de Santa Rita Sur, 23096 La Paz, B.C.S, Mexico Current literature considers that Nasolamia velox has a limited distribution along the coastline of the Eastern Pacific with sporadic sightings in the Galapagos Archipelago. This study provides evidence of the occurrence of this species at the Revillagigedo Archipelago (18899′186′′N 112808′44′′W), Mexico, using acoustic telemetry and videos taken from 2014 to 2016. We report here movements from a coastal location (National Park Cabo Pulmo) to a group of oceanic islands (Revillagigedo Archipelago) by one single individual, supporting the idea of the potential connectivity of sharks between the Gulf of California and the Revillagigedo Archipelago. This report extends the known distribution of N. velox to 400 km off the mainland coast of the Americas, thereby increasing the knowledge of the distribution of a species commonly reported in fishery landings of the Eastern Pacific. -

South of Hanko Peninsula

2013 5 CT JE RO SEA P C I T BAL Oceana proposal for a Marine Protected Area South of Hanko Peninsula INTRODUCTION Hanko Peninsula, located at the entrance to the Gulf of Finland, is the southern-most part of the Finnish mainland and boasts an archipelago and long sandy beaches. Salinity is relatively low, ranging from 5.5 to 7.5 psu, and the waters in the shallower coastal areas are limnic1. Upwellings, a common occurrence in the area wherein nutrient-rich sediments are brought up to the surface, cause a rapid increase in the salinity in areas at 35 meters, and a small increase in salinity in the surface water2. The inner waters of the archipelago freeze every year, while the more open waters freeze regularly, but not every winter3. Parts of the coastal area are protected under EU Natura 2000 network, and the area is classified as a sea area requiring specific protection measures. Wetland areas are also included in the Ramsar network. Because of the special characteristics of the area (changing salinity, archipelagos, wetlands), there are a lot of different zones that are able to host a wide variety of different species and communities4. Oceana conducted in the spring of 2011 and 2012 information from the area with ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle), bottom samples and scuba dives. 1 5 South of Hanko Peninsula DesCRipTION OF The AREA Low salinity limits the amount of marine species in the area. Species composition changes completely from the open waters to the coast; with marine species being more common further from the coast and limnic species getting more common closer to the shore. -

COASTAL WONDERS of NORWAY, the FAROE ISLANDS and ICELAND Current Route: Oslo, Norway to Reykjavik, Iceland

COASTAL WONDERS OF NORWAY, THE FAROE ISLANDS AND ICELAND Current route: Oslo, Norway to Reykjavik, Iceland 17 Days National Geographic Resolution 126 Guests Expeditions in: Jun From $22,470 to $44,280 * Call us at 1.800.397.3348 or call your Travel Agent. In Australia, call 1300.361.012 • www.expeditions.com DAY 1: Oslo, Norway padding Arrive in Oslo and check into the Hotel Bristol (or 2022 Departure Dates: similar) in the heart of the city. On an afternoon tour, stroll amid the city’s famed Vigeland 6 Jun sculptures—hundreds of life-size human figures Advance Payment: set in terraced Frogner Park. Visit the Fram Museum, showcasing the polar ship Fram and $3,000 dedicated to the explorers and wooden vessels that navigated the Arctic Sea in the late 1800s and Sample Airfares: early 1900s. The evening is free to explore Oslo Economy: from $900 on your own. (L) Business: from $2,700 Charter(Oslo/Tromso): from $490 DAY 2: Oslo / Tromsø / Embark Airfares are subject to change padding Take a charter flight to Tromsø, known as the Cost Includes: “gateway to the Arctic” due to the large number of Arctic expeditions that originated here. Visit the One hotel night in Oslo; accommodations; Arctic Cathedral, where the unique architecture meals indicated; alcoholic beverages evokes icebergs; and peruse the Polar Museum, (except premium brands); excursions; which showcases the ships, equipment, and services of Lindblad Expeditions’ Leader, seafaring traditions of early Arctic settlers. Embark Naturalist staff and expert guides; use of our ship this afternoon. (B,L,D) kayaks; entrance fees; all port charges and service taxes; gratuities to ship’s crew. -

The Finnish Archipelago Coast from AD 500 to 1550 – a Zone of Interaction

The Finnish Archipelago Coast from AD 500 to 1550 – a Zone of Interaction Tapani Tuovinen [email protected], [email protected] Abstract New archaeological, historical, paleoecological and onomastic evidence indicates Iron Age settle- ment on the archipelago coast of Uusimaa, a region which traditionally has been perceived as deso- lated during the Iron Age. This view, which has pertained to large parts of the archipelago coast, can be traced back to the early period of field archaeology, when an initial conception of the archipelago as an unsettled and insignificant territory took form. Over time, the idea has been rendered possible by the unbalance between the archaeological evidence and the written sources, the predominant trend of archaeology towards the mainland (the terrestrical paradigm), and the history culture of wilderness. Wilderness was an important platform for the nationalistic constructions of early Finnishness. The thesis about the Iron Age archipelago as an untouched no-man’s land was a history politically convenient tacit agreement between the Finnish- and the Swedish-minded scholars. It can be seen as a part of the post-war demand for a common view of history. A geographical model of the present-day archaeological, historical and palaeoecological evi- dence of the archipelago coast is suggested. Keywords: Finland, Iron Age, Middle Ages, archipelago, settlement studies, nationalism, history, culture, wilderness, borderlands. 1. The coastal Uusimaa revisited er the country had inhabitants at all during the Bronze Age (Aspelin 1875: 58). This drastic The early Finnish settlement archaeologists of- interpretation developed into a long-term re- ten treated the question of whether the country search tradition that contains the idea of easily was settled at all during the prehistory: were perishable human communities and abandoned people in some sense active there, or was the regions. -

Places on Deer Isle Open for Public Use

“The mission of Island Heritage Trust is to conserve significant open space, scenic areas, wildlife habitats, natural resources, historic and cultural features that offer public benefit and are essential to the character of the Deer Isle area.” Places on Deer Isle open for Public Use IHT’s Conserved Lands on Deer Isle Bowcat Point – On Little Deer Isle side of Causeway. Causeway Beach – Along Causeway between Little Deer Isle -Deer Isle. Reach Beach at Gray’s Cove – At far East end of Reach Road, Deer Isle. Lily Pond – Parking area off Deer Run Apartments Road, Deer Isle. Settlement Quarry – About ½ mile down Oceanville Road, Stonington (not on Settlement Road). Shore Acres – Off Greenlaw District Road (between Sunshine Road & Reach Road). Tennis Preserve –At end of Tennis Road off Sunshine Road, BPL land co- managed by IHT. Scotts Landing - North of and across from Causeway Beach, Deer Isle. Pine Hill – Off Blastow Cove Road, Little Deer Isle. Land owned by The Nature Conservancy maintained by IHT Barred Island Preserve - Near end of Goose Cove Road, Deer Isle. Crocket Cove Preserve - Off Whitman Road at Burnt Cove or off Barbour Farm Road, Stonington. IHT’s Conserved off-shore Islands open for day use Bradbury Island – Large Island in Penobscot Bay, West of Deer Isle. Carney Island – SW of Causeway Beach, IHT owns North half of Island Eagle nesting site, Island closed March –July. Mark Island (landing not recommended) – SW of Crotch Island. Millet Island – In Archipelago, NE of Spruce Island. Polypod Island – In Deer Isle’s Southeast Harbor. Round Island – In Archipelago, between McGlathery & Wreck. -

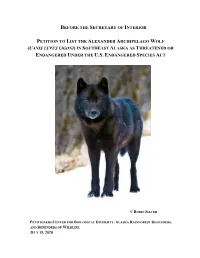

Petition to List the Alexander Archipelago Wolf in Southeast

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE ALEXANDER ARCHIPELAGO WOLF (CANIS LUPUS LIGONI) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT © ROBIN SILVER PETITIONERS CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, ALASKA RAINFOREST DEFENDERS, AND DEFENDERS OF WILDLIFE JULY 15, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Greg Siekaniec, Alaska Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road Anchorage, AK 99503 [email protected] PETITIONERS Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Larry Edwards Center for Biological Diversity Alaska Rainforest Defenders 1212 Broadway P.O. Box 6064 Oakland, California 94612 Sitka, Alaska 99835 (415) 385-5746 (907) 772-4403 [email protected] [email protected] Randi Spivak Patrick Lavin, J.D. Public Lands Program Director Defenders of Wildlife Center for Biological Diversity 441 W. 5th Avenue, Suite 302 (310) 779-4894 Anchorage, AK 99501 [email protected] (907) 276-9410 [email protected] _________________________ Date this 15 day of July 2020 2 Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Alaska Rainforest Defenders, and Defenders of Wildlife petition the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), to list the Alexander Archipelago wolf (Canis lupus ligoni) in Southeast Alaska as a threatened or endangered species. -

Postglacial Isostatic Movement in Northeastern Devon Island, Canadian Arctic Archipelago

POSTGLACIAL ISOSTATIC MOVEMENTIN NORTHEASTERNDEVON ISLAND, CANADIAN ARCTIC ARCHIPELAGO F. Muller* and W. Barr* ABSTRACT. Raised marinefeatures of the lowlands in the vicinity of Cape Sparbo were investigated. The carbon14 dates of marine shells indicate that the area was clear of ice as early as 15,500 before present and that the most rapid isostatic uplift (approx. 6.5 m. .per century) took place between 9,000 and 8,000 years ago; the total isostatic rebound having been about 110 m. The two oldest dates (15,000 and 13,000 B.P.), if correct, give a rare indication of the slow onset of the isostatic uplift. Rl?SUMl?. Isostasie postglaciaire dans le nord-est de rile Devon, Archipel Arctique canadien. Les auteurs ont CtudiC la morphologie isostatique des basses terres au voisinage du cap Sparbo. Les datations par lecarbonel4 de coquillages marins indiquentque larCgion Ctait libre de glace dbs 15,500 av. p. etque le relbvement leplus rapide (approx. 6.5 m. par sibcle) s’est produit entre le neuvibme et le huitibme millhaire av. p. Le rebondissement isostatique, total a CtC denviron 110 m. Les deux datations les plus anciennes (15,000 et 13,000 av. p.), SI elles sont justes, sont une rare preuve de la lenteur du relbvement son debut. ASCTPAKT.nOCJlEJlEAHMKOBOE HSOCTATH’IECKOE ABHMEHME CEBEPOB - BOCTOqHOU’IACTH OCT,POBA AEBOH, KaHaAcKHeApKTHWCHHe oclposa. Hccne&yIOTca MopcKae nepm xapamepa HHaMeHHOCTH,IIO&HJTBIUe%Ca ~3 MOPJI B paiioHe Mma CnapGo. OnpeReneme ~ospac~apaKymeK yrnepoAmM (14) MeTOAOM yIcaamaeT, ¶TO pa%oH DTOT BMJI cBoGoReH OTO nqa yxe 15000 aeT TOMY ~aaa~,E ~ITO ~aaBonee 6HCTpOe H~OCT~TEP~CIIO~ IIOAHsITHe(JIpH6JIH3HTeJIbHO 6,5 MeTpOB B CTOJIeTHB)HMelO MeCTO MeXCAY 9000 H 8000 TOMY asa ax. -

Island Locations and Classifications Christian Depraetere Arthur L

Chapter 2 Island Locations and Classifications Christian Depraetere Arthur L. Dahl Definitions Defining an island, or the state of'islandness', is never straightforward, though this is fundamentally a question of isolation, whether of land isolated by water, or of one enriry being separated from others. This chapter adopts a positivist approach to explore the geographic realities behind our concept ofislands. There is in fact a continuum ofgeographic entities that can fit the definition of "a piece of land surrounded by water": from the continent of Eurasia to the rock on a beach lapped by the waves that becomes a child's imaginary island. Drawing the line between something that is too large to be an island, or too small ro be an island, ultimately remains an arbitrary decision. If one concurs with Holm (2000) that "an island is whatever we call an island", we can select from the traditional uses, the convenient distinctions and arbitrary choices of the past, a terminology for islands that corresponds to scientific observations gleaned from geological, biological and human perspectives. Fortunately, the new tools of remote sensing satellite imagery (such as WORLDWIND for global LAt'\JDSAT imagery by NASA: http: //worldwind.arc.nasa.gov/) provide data sets that make possible for the first time some globally consistent and homogenous measurements of that 'world archipelago' made up ofall those pieces ofland surrounded by water. At the same time, our understanding of geotecwnic movements, sea level changes and island-building processes allows us to see the oceanic 57 A World ofIslands: An Island Studies Reader Island Locations and Classifications islands of today not as erernal entities but as one static image captured The World Archipelago from ongoing processes of islands growing and shrinking, joining and The wor/d during antiquiry as illustrated in the work of Herodotus, being separated, appearing and disappearing through time. -

To Make an Archipelago!

Hohonu Moana: Exploring Deep Waters Off Hawaii Expedition 2015 To Make an Archipelago! Grade Level 6-8 (Earth Science) Focus Formation of the Hawaiian Archipelago Focus Question What geological processes produced the different physical forms seen among islands in the Hawaiian Archipelago? Learning Objectives n Students will describe eight stages in the formation of islands in the Hawaiian Archipelago, and will describe how a combination of hotspot activity and tectonic plate movement could produce the arrangement of seamounts observed in the Hawaiian Archipelago. n Students will construct a scientific explanation based on evidence for how a combination of hotspot activity and tectonic plate movement could produce the distributions of cobalt-rich ferromanganese resources found in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Materials q Diagram of “The Hawaiian Archipelago” (Download from http://www. soest.hawaii.edu/GG/HCV/haw_formation.html) q Map of the Hawaiian Archipelago (e.g., http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/ science/condition/pmnm/images/fig1_lg.jpg) q Materials for constructing island models OR drawing materials OR student Internet access, depending upon option chosen for Learning Procedure Step #4 q Brief description of selected islands (see Learning Procedure step #4; http://www.bishopmuseum.org/research/nwhi/geograph.html is a useful source for this information) Audio-Visual Materials Image captions/credits on Page 2. q (Optional) Interactive white board Teaching Time Two to three 45-minute class periods 1 www.oceanexplorer.noaa.gov To Make an Archipelago! Grades 6-8 (Earth Science) Seating Arrangement Groups of two to four students Maximum Number of Students 30 Key Words archipelago atoll Marine National Monument cobalt ferromanganese crust seamount lithosphere hotspot tectonic plate Background Information Marine protected areas (MPAs) are areas of the marine environment where there is legal protection for natural and cultural resources. -

Biodiversity and Management of the Madrean Archipelago: the Sky

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. The Madrean Sky Island Archipelago: A Planetary Overview Peter Warshall 1 Abstract.-Previous work on biogeographic isolation has concerned itself with oceanic island chains, islands associated with continents, fringing archipelagos, and bodies of water such as the African lake system which serve as "aquatic islands". This paper reviews the "continental islands" and compares them to the Madrean sky island archipelago. The geological, hydrological, and climatic context for the Afroalpine, Guyana, Paramo, low and high desert of the Great Basin, etc. archipelagos are compared for source areas, number of islands, isolating mechanisms, interactive ecosystems, and evolutionary history. The history of scientific exploration and fieldwork for the Madrean Archipelago and its unique status among the planet's archipelagos are summarized. In 1957, Joe Marshall published "Birds of the American Prairies Province of Takhtajan, 1986) Pine-Oak Woodland in Southern Arizona and Ad and western biogeographic provinces, a wealth of jacent Mexico." Never surpassed, this elegant genetically unique cultivars in the Sierra Madre monograph described the stacking of biotic com Occidental, and a myriad of mysteries concerning munities on each island mountain from the the distribution of disjuncts, species "holes," and Mogollon Rim to the Sierra Madre. He defined the species II outliers" on individual mountains (e.g., Madrean archipelago as those island mountains Ramamoorthy, 1993). The northernmost sky is with a pine-oak woodland. In 1967, Weldon Heald lands are the only place in North America where (1993), from his home in the Chiricahuas, coined you can climb from the desert to northern Canada the addictive phrase-"sky islands" for these in in a matter of hours (Warshall, 1986). -

THE INDIAN OCEAN the GEOLOGY of ITS BORDERING LANDS and the CONFIGURATION of ITS FLOOR by James F

0 CX) !'f) I a. <( ~ DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE INDIAN OCEAN THE GEOLOGY OF ITS BORDERING LANDS AND THE CONFIGURATION OF ITS FLOOR By James F. Pepper and Gail M. Everhart MISCELLANEOUS GEOLOGIC INVESTIGATIONS MAP I-380 0 CX) !'f) PUBLISHED BY THE U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY I - ], WASHINGTON, D. C. a. 1963 <( :E DEPARTMEI'fr OF THE ltfrERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP J-S80 UNITED STATES OEOLOOICAL SURVEY THE lliDIAN OCEAN THE GEOLOGY OF ITS BORDERING LANDS AND THE CONFIGURATION OF ITS FLOOR By James F. Pepper and Gail M. Everhart INTRODUCTION The ocean realm, which covers more than 70percent of ancient crustal forces. The patterns of trend of the earth's surface, contains vast areas that have lines or "grain" in the shield areas are closely re scarcely been touched by exploration. The best'known lated to the ancient "ground blocks" of the continent parts of the sea floor lie close to the borders of the and ocean bottoms as outlined by Cloos (1948), who continents, where numerous soundings have been states: "It seems from early geological time the charted as an aid to navigation. Yet, within this part crust has been divided into polygonal fields or blocks of the sea floQr, which constitutes a border zone be of considerable thickness and solidarity and that this tween the toast and the ocean deeps, much more de primary division formed and orientated later move tailed information is needed about the character of ments." the topography and geology. At many places, strati graphic and structural features on the coast extend Block structures of this kind were noted by Krenke! offshore, but their relationships to the rocks of the (1925-38, fig.