Island Locations and Classifications Christian Depraetere Arthur L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atoll Research Bulletin

0-v Nos. 12, 13, 14 December 15, 1952 ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 12 Preliminary Report on Geology and Marine Environments of Onotoa Atoll, Gilbert Islands by Preston E. Cloud, Jr. 13. Preliminary Report on Marine Biology Study of Onotoa Atoll, Gilbert Islands by A. H. Banner and J. E. Randall ^ 14. Description of Kayangel Atoll, Palau Islands by J. L. Gressitt m^^m Issued by THE PACIFIC SCIENCE BOARD National Academy of Sciences—^National Research Council Washington, D. C, U.S.A. ATOLL RESGLbRCII BUILETIIJ 12. Preliminarj'" Report on Geo2.og^' and Mo.rine Environnients of Onotoa Atoll, Gilbert Islands hy Preston E. G3.oud, Jr. 13. Preljjninary Report on Marine Biology Study of Onotoa Atoll, Gilbert Islands by A. H. Banner and J. E. Randall 14. Description of Kayangel Atoll, Palau Islands by J. L. Gressitt Issued by THE PACIFIC SCIENCE BOARD National Academy of vSciences—National Research Council Washington, D.C. December 15, 1952 . ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN No. U Description of. Keyangel Atoll, Palau Islands by J. L. Gressitt Issued by THE PACIFIC SGIEi^CE BOARD National Academy of Sciences—National Research Council Washington , D . C December 15, 1952 DESCRIPTION OF KAYANGEL ATOLL, PALAU ISLANDS By J. L. Gressitt Pacific Science Board , Kayangel Atoll is the northernmost land area of the Palau Archipelago in the western Caroline Islands, except for Ngaruangl, a sand bank on an incipient atoll to its north. There are no other atolls v/ithin 150 miles. Kaj'-angel is separated from Babelthuap, the largest island of the Palatis and a volcanic is- land, by about tv/enty miles of water. -

This Keyword List Contains Indian Ocean Place Names of Coral Reefs, Islands, Bays and Other Geographic Features in a Hierarchical Structure

CoRIS Place Keyword Thesaurus by Ocean - 8/9/2016 Indian Ocean This keyword list contains Indian Ocean place names of coral reefs, islands, bays and other geographic features in a hierarchical structure. For example, the first name on the list - Bird Islet - is part of the Addu Atoll, which is in the Indian Ocean. The leading label - OCEAN BASIN - indicates this list is organized according to ocean, sea, and geographic names rather than country place names. The list is sorted alphabetically. The same names are available from “Place Keywords by Country/Territory - Indian Ocean” but sorted by country and territory name. Each place name is followed by a unique identifier enclosed in parentheses. The identifier is made up of the latitude and longitude in whole degrees of the place location, followed by a four digit number. The number is used to uniquely identify multiple places that are located at the same latitude and longitude. For example, the first place name “Bird Islet” has a unique identifier of “00S073E0013”. From that we see that Bird Islet is located at 00 degrees south (S) and 073 degrees east (E). It is place number 0013 at that latitude and longitude. (Note: some long lines wrapped, placing the unique identifier on the following line.) This is a reformatted version of a list that was obtained from ReefBase. OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bird Islet (00S073E0013) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Bushy Islet (00S073E0014) OCEAN BASIN > Indian Ocean > Addu Atoll > Fedu Island (00S073E0008) -

Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, 1973-82

Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea 1973-1982 Concluded at Montego Bay, Jamaica on 10 December 1982 Document:- A/CONF.62/C.2/L.62/Rev.1 Algeria, Dahomey, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tunisia, Upper Volta and Zambia: draft articles on the regime of islands Extract from the Official Records of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Volume III (Documents of the Conference, First and Second Sessions) \ Copyright © United Nations 2009 232 Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea DOCUMENT A/CONF.62/C.2/L.62/Rev. 1 Algeria, Dahomey, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tunisia, Upper Volta and Zambia: draft articles on the regime of islands [Original: French] [27 August 1974] Article I Article 2 1. An island is a vast naturally formed area of land, sur- \: The baselines applicable to adjacent islands, islets, rocks rounded by water, which is above water at high tide. and low-tide elevations, in accordance with article 1, are con- 2. An islet is a smaller naturally formed area of land, sur- sidered as the baselines applicable to the State to which they rounded by water, which is above water at high tide. belong and consequently are used in the measurement of the marine spaces of that State. 3. A rock is a naturally formed rocky elevation of ground, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide. 2. The marine spaces of islands considered non-adjacent, in accordance with paragraphs 1 and 6, shall be delimited on the 4. -

Kinmen Reopens Jiangong Islet to Public

Kinmen reopens Jiangong Islet to public Taipei, Feb. 26 (CNA) Large numbers of tourists have visited Jiangong Islet in Kinmen County since it was recently re-opened to the public, and its rich ecosystem amazes visitors as they walk the stone path in the islet's intertidal zone. Chen Mei-ling (陳美齡), head of the tourism department of the offshore county, said Chinese-English bilingual tourist information is now available to visitors, while new wooden platforms, viewing decks and seashore trails have been built on the islet to provide more comprehensive services to visitors after it was reopened to the public in late January following reconstruction from Dec. 20 last year. The islet, located at the mouth of the Wu River in Jincheng Township and originally named Chu Islet, is 500 meters away from the Kinmen Island and covers 500 square meters. In 1949, it was taken by the Republic of China armed forces, which built stronghold W038 on it in the face of Chinese attacks from the other side of the Taiwan Strait, at a time when the two sides were still at war after the ROC government retreated to Taiwan. It was given the name of Jiangong Islet in 1960 and remained under the control of the ROC military until 1997, when the troops were all withdrawn as part of a military streamlining program. Since then, the islet gradually became dilapidated through lack of care until 2002, when the county government took it over and started repairs in the area with the aim of turning it into a tourist attraction. -

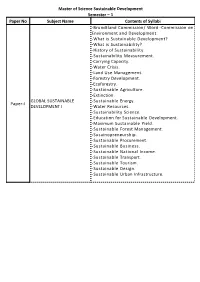

Master of Science Sustainable Development Semester – 1 Paper

Master of Science Sustainable Development Semester – 1 Paper No Subject Name Contents of Syllabi -Brundtland Commission/ Word -Commission on Environment and Development. -What is Sustainable Development? -What is Sustainability? -History of Sustainability. -Sustainability Measurement. -Carrying Capacity. -Water Crisis. -Land Use Management. -Forestry Development. -Ecoforestry. -Sustainable Agriculture. -Extinction. GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE -Sustainable Energy. Paper-I DEVELOPMENT I -Water Resources. -Sustainability Science. -Education for Sustainable Development. -Maximum Sustainable Yield. -Sustainable Forest Management. -Susainopreneurship. -Sustainable Procurement. -Sustainable Business. -Sustainable National Income. -Sustainable Transport. -Sustainable Tourism. -Sustainable Design. -Sustainable Urban Infrastructure. Master of Science Sustainable Development -What is Biodiversity? -Measurement of Biodiversity. -Species Richness. -Shannon Index. -2010 Biodiversity Indicators- Partnership. -Evolution. -Evolutionary Thought. -How does Evolution Occur? -Timeline of Evolution. BIODIVERSITY -Social Effect of Evolutionary Theory. Paper-II CONSERVATION & -Objections of Evolution. MANAGEMENT I -Population Genetics. -Genetics. -Heredity. -Mutation. -Molecular Evolution. -Genetic Recombination. -Sexual Reproduction. -Gene Flow. -Hybrid. -What is Energy? -History of Energy. -Timeline of Thermodynamics. -Units of Energy. -Potential Energy. -Elastic Energy. -Kinetic Energy. -Internal Energy. -Electromagnetism. -Electricity. GLOBAL ENERGY POLICIES Paper-III -

Iucn Summary Gough Island (United Kingdom) 2

WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION - IUCN SUMMARY GOUGH ISLAND (UNITED KINGDOM) Summary prepared by IUCN/WCMC (March 1995) based on the original nomination supplied by the Government of the United Kingdom. This original and all documents in support of this nomination will be available for consultation at the meetings of the Bureau and the Committee. 1. LOCATION Located southeast of Tristan da Cunha Island in the south Atlantic Ocean, midway between Africa and South America. 2. JURIDICAL DATA The island and surrounding territorial waters were designated a wildlife area in 1976 under the Tristan da Cunha Conservation Ordinance. 3. IDENTIFICATION The island of Gough (6500ha) represents the eroded core of a Late Tertiary volcano. The east side of the island is dissected by a series of deep steep-sided valleys, which are separated by narrow serrated ridges. Along the west side of the island, rounded slopes extend from the central plateau to the western sea cliffs. Many offshore stacks and rocks are present, mostly within 100m of the main island. Vegetation comprises tussock grass around the coast and wet heath with moss and feldmark, and bog and swamp communities at higher elevations. Knowledge of the flora is incomplete but consists of some 35 native flowering plant and 28 native fern species. Over 30 of Gough's vascular plant taxa are endemic to the Tristan de Cunha islands. A total of 146 bryophytes have been recorded, eight of which are endemic, together with 20 fungi and 24 lichens. Invertebrate fauna also remains poorly known, but comprises 100 species, eight of which are endemic. -

Range Expansion of the Whitenose Shark, Nasolamia Velox, and Migratory Movements to the Oceanic Revillagigedo Archipelago

Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, page 1 of 5. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2017 doi:10.1017/S0025315417000108 Range expansion of the whitenose shark, Nasolamia velox, and migratory movements to the oceanic Revillagigedo Archipelago (west Mexico) frida lara-lizardi1,2, mauricio hoyos-padilla2,3, james t. ketchum2,4 and felipe galva’ n-magan~a1 1Instituto Polite´cnico Nacional, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas, Av. IPN s/n. C.P. 23096. La Paz, B.C.S, Mexico, 2Pelagios-Kakunja´ A. C. 1540 Sinaloa, C.P. 23070, La Paz, B.C.S., Mexico, 3Fins Attached, 19675 Still Glen Way, Colorado Springs, CO 80908, USA, 4Centro de Investigaciones Biolo´gicas del Noroeste, Playa Palo de Santa Rita Sur, 23096 La Paz, B.C.S, Mexico Current literature considers that Nasolamia velox has a limited distribution along the coastline of the Eastern Pacific with sporadic sightings in the Galapagos Archipelago. This study provides evidence of the occurrence of this species at the Revillagigedo Archipelago (18899′186′′N 112808′44′′W), Mexico, using acoustic telemetry and videos taken from 2014 to 2016. We report here movements from a coastal location (National Park Cabo Pulmo) to a group of oceanic islands (Revillagigedo Archipelago) by one single individual, supporting the idea of the potential connectivity of sharks between the Gulf of California and the Revillagigedo Archipelago. This report extends the known distribution of N. velox to 400 km off the mainland coast of the Americas, thereby increasing the knowledge of the distribution of a species commonly reported in fishery landings of the Eastern Pacific. -

Henderson Island Expedition June 2019 Henderson Island Expedition June 2019

Henderson Island Expedition June 2019 Henderson Island Expedition June 2019 Overview Overarching objectives of the expedition: A) Study the plastic pollution on Henderson Island and raise awareness of the waste in the context of the global problem of ocean plastics; B) Study and raise awareness of the Henderson marine environment – promoting the Pitcairn Island Marine Reserve and the benefits of large, fully protected marine protected areas. A 2015 analysis (published in 2017) found that one of the Pitcairn archipelago’s four islands, Henderson, has >18 tonnes of plastic on its beaches: “the highest density of plastic debris recorded anywhere in the world”. The 38km2 island has >38 million pieces of plastic upon its shores. Conservative estimates suggest that 3,500-13,500 new plastic items wash up on Henderson each day. One of its beaches, the 2 km long East Beach, is polluted by 30 million plastic items. The 2015 work served as a reminder that the long-term protection of large areas of ocean needs to be partnered by science and messaging capable of changing attitudes towards the way we live, consume, and discard on land. The Pitcairn Island Council has sanctioned an expedition to Henderson in June 2019 which provides an opportunity for key Pitcairn and ocean stakeholders to effectively communicate the source, scale, range and impacts of ocean debris on Henderson and the Pacific Ocean through on-site science, art and media. The initiative also provides the team an opportunity to study and showcase the beauty and ambition of the Pitcairn Island Marine Reserve Henderson Island Expedition June 2019 MEXICO Timings PACIFIC OCEAN 1 02/06 Arrive at Tahiti Team briefing Tahiti 2 04/06 PERU Depart Tahiti 07:30 a.m. -

An Early Sophisticated East Polynesian Voyaging Canoe Discovered on New Zealand’S Coast

An early sophisticated East Polynesian voyaging canoe discovered on New Zealand’s coast Dilys A. Johnsa,1, Geoffrey J. Irwina, and Yun K. Sungb aAnthropology Department, School of Social Sciences, and bSchool of Architecture and Planning, University of Auckland, Auckland 1142, New Zealand Edited by Patrick V. Kirch, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved August 19, 2014 (received for review May 9, 2014) The colonization of the islands of East Polynesia was a remarkable wide at its widest point and 76 cm at the butt end. Lashing holes episode in the history of human migration and seafaring. We around all edges have been chiseled transversely through the timber report on an ocean-sailing canoe dating from close to that time. and the canoe averages 5-cm thick at lashing holes. The internal A large section of a complex composite canoe was discovered surface is finished with regular adzing and the outside surface recently at Anaweka on the New Zealand coast. The canoe dates carefully smoothed to prevent drag through the water. The edges to approximately A.D. 1400 and was contemporary with continu- are flat and evenly finished by abrasion or possibly sawing (15, 16), ing interisland voyaging. It was built in New Zealand as an early where they were attached to adjoining parts of the canoe. adaptation to a new environment, and a sea turtle carved on its Striking features of the hull are four transverse ribs carved at hull makes symbolic connections with wider Polynesian culture intervals along the hull, and a straight longitudinal stringer or and art. -

Dubai 2020: Dreamscapes, Mega Malls and Spaces of Post-Modernity

Dubai 2020: Dreamscapes, Mega Malls and Spaces of Post-Modernity Dubai’s hosting of the 2020 Expo further authenticates its status as an example of an emerging Arab city that displays modernity through sequences of fragmented urban- scapes, and introvert spaces. The 2020 Expo is expected to reinforce the image of Dubai as a city of hybrid architectures and new forms of urbanism, marked by technologically advanced infrastructural systems. This paper revisits Dubai’s spaces of the spectacle such as the Burj Khalifa and themed mega malls, to highlight the power of these spaces of repre- sentation in shaping Dubai’s image and identity. INTRODUCTION MOHAMED EL AMROUSI Initially, a port city with an Indo-Persian mercantile community, Dubai’s devel- Abu Dhabi University opment along the Creek or Khor Dubai shaped a unique form of city that is con- stantly reinventing itself. Its historic adobe courtyard houses, with traditional PAOLO CARATELLI wind towers-barjeel sprawling along the Dubai Creek have been fully restored Abu Dhabi University to become heritage houses and museums, while their essential architectural vocabulary has been dismembered and re-membered as a simulacra in high-end SADEKA SHAKOUR resorts such as Madinat Jumeirah, the Miraj Hotel and Bab Al-Shams. Dubai’s Abu Dhabi University interest to make headlines of the international media fostered major investment in an endless vocabulary of forms and fragments to create architectural specta- cles. Contemporary Dubai is experienced through symbolic imprints of multiple policies framed within an urban context to project an image of a city offers luxu- rious dreamscapes, assembled in discontinued urban centers. -

From the Mascarene Islands

58 New species of Cryptophagidae and Erotylidae (Coleoptera) from the Mascarene Islands New species of Cryptophagidae and Erotylidae (Coleoptera) from the Mascarene Islands GEORGY YU. LYUBARSKY Zoological Museum of Moscow State University, Bolshaya Nikitskaya ulica 6, 125009, Moscow, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] LYUBARSKI G.Yu. 2013. NEW SPECIES OF CRYPTOPHAGIDAE AND EROTYLIDAE (COLEOPTERA) FROM THE MASCARENE ISLANDS. – Latvijas Entomologs 52: 58-67. Abstract: А new species Micrambe reunionensis sp. nov. (Cryptophagidae) is described from the island of La Réunion. Cryptophilus integer (HEER, 1841) and Leucohimatium arundinaceum (FORSKAL, 1775) (Erotylidae) proved new for the Mascarene faunal district. Key words: Cryptophagidae, Erotylidae, Cryptophilus, Leucohimatium, Micrambe, La Réunion, Mascarene Archipelago. Mascarene Islands: natural conditions many recent extinctions. Volcanic islands with higher elevations The Mascarenes is an island group are relatively young. The most /ancient lavas in the south-western Indian Ocean, 700 from La Réunion are dated at 2.1 million km east of Madagascar. Commonly, it is years ago. La Réunion has been suitable subdivided into continental and oceanic for life since about 2–3 million years ago islands, and oceanic islands are further (Thébaud et al. 2009). La Réunion possesses divided into volcanic islands and coral one active and three extinct volcanoes. The islands. The archipelago includes three high island is dissected by huge caldera-like volcanic islands (La Réunion, Mauritius and valleys (cirques) created by heavy rainfall Rodrigues). Mauritius was the former home of erosion, with very deep gorges culminating dodo, the universal symbol of human-caused in narrow outlets to the sea. species extinction on the islands. -

British Virgin Islands

British Virgin Islands Clive Petrovic, Esther Georges and Nancy Woodfield Andy McGowan Great Tobago General introduction The British Virgin Islands comprise more than 60 islands, and the Virgin Islands. These include the globally cays and rocks, with a total land area of approximately 58 threatened Cordia rupicola (CR), Maytenus cymosa (EN) and square miles (150 square km). This archipelago is located Acacia anegadensis (CR). on the Puerto Rican Bank in the north-east Caribbean at A quarter of the 24 reptiles and amphibians identified are approximately 18˚N and 64˚W. The islands once formed a endemic, including the Anegada Rock Iguana Cyclura continuous land mass with the US Virgin Islands and pinguis (CR), which is now restricted to Anegada. Other Puerto Rico, and were isolated only in relatively recent endemics include Anolis ernestwilliamsii, Eleutherodactylus geologic time. With the exception of the limestone island of schwartzi, the Anegada Ground Snake Alsophis portoricensis Anegada, the islands are volcanic in origin and are mostly anegadae, the Virgin Gorda Gecko Sphaerodactylus steep-sided with rugged topographic features and little flat parthenopian, the Virgin Gorda Worm Snake Typlops richardi land, surrounded by coral reefs. naugus, and the Anegada Worm Snake Typlops richardi Situated at the eastern end of the Greater Antilles chain, the catapontus. Other globally threatened reptiles within the islands experience a dry sub-tropical climate dominated by BVI include the Anolis roosevelti (CR) and Epicrates monensis the prevailing north-east trade winds. Maximum summer granti (EN). temperatures reach 31˚C; minimum winter temperatures Habitat alteration during the plantation era and the are 19˚C, and there is an average rainfall of 700 mm per introduction of invasive alien species has had major year with seasonal hurricane events.