Triple Witching Hour" on Stock Market Volatility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scapegoat Study Guide

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Helms School of Government 2003 René Girard: The Scapegoat Study Guide Steven Alan Samson Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Samson, Steven Alan, "René Girard: The Scapegoat Study Guide" (2003). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 108. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs/108 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Helms School of Government at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RENÉ GIRARD: THE SCAPEGOAT STUDY GUIDE, 2003 Steven Alan Samson CHAPTER ONE: GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT AND THE JEWS Study Questions 1. What are some of the catastrophic events Machaut describes? What led to the massacre of the Jews? How is the process of scapegoating described in a fable by Jean La Fontaine? [The tendency to euphemize an evil is similarly depicted in the Harry Potter stories, as, for example, with "He who must not be named"]. (1-3) 2. [SKIP] How does Machaut's account of the arrival of the plague illustrate the phenomenon of scapegoating? What makes Machaut's use of epydimie [epidemic] a "linguistic scapegoat" and how is its essential structure the same as a human sacrifice? Does he ever connect these events into a single entity? ["The Thirty Years War" and "The Hundred Years War" were, of course, not perceived as such at the time]. -

Campaign Guide the CIRCLE UNDONE

Campaign Guide THE CIRCLE UNDONE Death Is Only the Beginning Haunted “The hidden cults to which these witches belonged often guarded Haunted is a new ability that appears on some locations. Each time and handed down surprising secrets from elder, forgotten aeons; an investigator fails a skill test while investigating a location, after and it was by no means impossible that Keziah had actually applying all results for that skill test, that investigator must resolve all mastered the art of passing through dimensional gates.” “Haunted –” abilities on that location. – H. P. Lovecraft, The Dreams in the Witch House A location is “haunted” for the purposes of other card effects if it has at least one “Haunted –” ability (printed or otherwise). The Circle Undone is a campaign for Arkham Horror: The Card Game for 1–4 players. The Circle Undone deluxe expansion contains a prologue scenario, “Disappearance at the Twilight Estate,” and two Alert full scenarios: “The Witching Hour” and “At Death’s Doorstep.” Each time an investigator fails a skill test while attempting to evade These scenarios can be played on their own or combined with an enemy with the “alert” keyword, after applying all results for the six Mythos Packs in The Circle Undone cycle to form a larger that skill test, that enemy performs an attack against the evading nine‑part campaign. investigator. An enemy does not exhaust after performing an alert attack. This attack occurs whether the enemy is engaged with the Additional Rules and Clarifications evading investigator or not. Tarot Slot Prologue Investigators 1 3 Jerome Davids 21 4 4 Valentino Rivas Josef’s Secretary Wealthy Philanthropist The four investigator cards 2 Penny1 White3 2 Assistant. -

The Witching Hour by Francie Mcgowan

The Witching Hour By Francie McGowan Next week’s Halloween night, under a waxing crescent moon, is when, according to legend, the veil between the living and the dead is at its thinnest, and houls, goblins, witches and ghosts are on the prowl. In western tradition, the “witching hour” is between 3 and 4 am. This is when the evil demons of the night are at their most powerful. One of the most infamous of these evil spirits is the witch. The witch, as portrayed in lore and in literature, has been maligned by superstition and by writers - the most famous, of course, is Shakespeare. In “Macbeth,” Shakespeare’s witches (he calls them the weird sisters) make a potion for their evil deeds: Fillet of a fenny snake, In the cauldron boil and bake; Eye of newt and toe of frog, Wool of bat and tongue of dog, Adder's fork and blind-worm's sting, Lizard's leg and owlet's wing, For a charm of powerful trouble, Like a hell-broth boil and bubble. They go on to add all sorts of ghastly ingredients, including, “root of hemlock, digg’d i’ the dark,” and “Gall of goat, and slips of yew silver’d in the moon’s eclipse.” Shakespeare’s witches have beards and cackle, and pretty much resemble what has come down to us as the quintessential Halloween witch. Women in medieval times who were herbalists and healers, often were thought to be witches and up to no good. Their knowledge of chemistry and botany was threatening to the superstitious populace of the 12th and 13th centuries. -

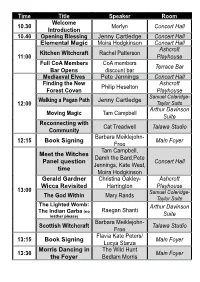

Time Title Speaker Room 10.30 Welcome Introduction Merlyn

Time Title Speaker Room Welcome 10.30 Merlyn Concert Hall Introduction 10.40 Opening Blessing Jenny Cartledge Concert Hall Elemental Magic Moira Hodgkinson Concert Hall Ashcroft Kitchen Witchcraft Rachel Patterson 11:00 Playhouse Full CoA Members CoA members Terrace Bar Bar Opens discount bar Mediaeval Elves Pete Jennings Concert Hall Finding the New Ashcroft Philip Heselton Forest Coven Playhouse Samuel Coleridge- Walking a Pagan Path Jenny Cartledge 12:00 Taylor Suite Arthur Davinson Moving Magic Tam Campbell Suite Reconnecting with Cat Treadwell Talawa Studio Community Barbara Meiklejohn- 12:15 Book Signing Main Foyer Free Tam Campbell, Meet the Witches Damh the Bard,Pete Panel question Concert Hall Jennings, Kate West, time Moira Hodgkinson Gerald Gardner Christina Oakley- Ashcroft Wicca Revisited Harrington Playhouse 13:00 Samuel Coleridge- Mary Rands The God Within Taylor Suite The Lighted Womb: Arthur Davinson The Indian Garba (no Raegan Shanti leather please) Suite Barbara Meiklejohn- Scottish Witchcraft Talawa Studio Free Flavia Kate Peters/ 13:15 Book Signing Main Foyer Lucya Starza Morris Dancing in The Wild Hunt 13:30 Main Foyer the Foyer Bedlam Morris Time Title Speaker Room A Question and Maxine Sanders Concert Hall Answer Session Ashcroft Pagan Grail Damh the Bard Playhouse The Crow Mythically Samuel Coleridge- 14:00 Diane Narraway and Spiritually Taylor Suite Moon Magic Teresa Dellbridge Talawa Studio The Wild Hunt Arthur Davinson Morris Dancing Bedlam Morris Suite Photo Booth Opens Free Photos Main Foyer Cat Treadwell/Pete 14:15 Book Signing Main Foyer Jennings Mystery of Witchcraft Kate West Concert Hall The Magic of the Ashcroft Rufus Harrington Mind Playhouse Kemeticism and Samuel Coleridge- 15:00 Kevin Groves Chaos Magic Taylor Suite The Power of the Arthur Davinson Zarah Voice Suite Witches’ Familiars Flavia Kate Peters Talawa Studio 15:15 Book Signing Moira Hodgkinson Main Foyer The Wicker Man Prof. -

The Coven Zealots of the Veil Denizens of Chaos

THE COVEN ZEALOTS OF THE DENIZENS OF Cultist VEIL CHAOS Notoriety x1 Exorcist C’thonian Burnt Offering x5 Contrition x5 Notoriety x1 Sacrificial Blade x1 Expel x1 Incubation Chamber x5 Dying Curse x1 Dispel x1 Tendrils from Beyond x2 Sense Evil x1 Witch Red Queen Dispel x1 Witcher Dispel x1 Spirit Cooking x5 Dispelx1 Catharsis x5 Spirit speak x1 Magic Find x4 Organism x2 Counterspell x1 Spell ward x3 AGRO TRAPS AGRO Internalize x2 Arcane Lock (Trap) x1 Adjudicate x2 Nether Blast x3 Tether (Trap) x1 Baal Fire x2 Tentacle x2 Wither (Trap) x1 Burn at the Stake x2 Volans Pasta Monstrum x3 Purify x1 Blood Harvest x1 AGRO Crusader x2 Singularity x1 Cretin x3 Dark Ward x2 Disease x2 Witching Hour x1 The Black Cauldron x1 CONTROL Hellfire Curse x2 The Void x2 Vile Rite x2 CONTROL Monolith x2 Behemoth x1 Defend x2 Asphyxiate x2 Teleport x2 Imprison x1 CONTROL Disciple x2 Initiator x2 Channel x2 Turn Undead x2 Hiver x2 Consume x3 Binding Ward x1 Engineer x1 Circle of Death x1 Exorcism x2 Summon x1 For Whom the Bell Tolls x1 SUPPORT Leviathan x3 Spores x2 Demonic Curse x1 Virus x2 SUPPORT Blighter x3 Holy Ground x3 Madness x2 SUPPORT Knowledge of Good and Evil x3 Under Dweller x2 Human Sacrifice x2 Cure x2 Infestation x1 Poison Nova x2 Nexus x1 Book of Groal x1 Protection Wardx1 Abomination x3 Sanctity Wardx1 Poison Missile x2 Deliver us from Evil x1 Poison Maelstrom x1 DEMONS OF SHEOL ANGELS OF HEROES APOCALYPSE EXPANSION Imp Herald Hellfire Portal x4 Dispel x1 Summoner (The Coven) Fire Shield x4 Dispel x1 Degradation x3 Cantrip x4 Demoness Fulfillment -

Download Enchantment Is All About Us for FREE

In Enchantment is All About Us Beatrice Walditchreveals that much of the what we often think of a real in the modern world is an enchantment woven by profit-driven businesses and nefarious politicians. Drawing upon a wide range of traditional worldviews, she sets out ways of mentally ‘banishing’ such pervasive enchantments and empowering the reader to create their own enchantments. Many of the suggestions develop and weave together ideas discussed in her previous books. Enchantment is All About Us is the fifth book in the Living in a Magical World series. These books will challenge you to recognisethe traditional magic still alive in modern society, and empower you with a variety of skills and insights. Previous books by BeatriceWalditch from Heart of Albion You Don't Just Drink It! What you need to know – and do – before drinking mead Listening to the Stones (Volume One of the Living in a Magical World series) Knowing Your Guardians (Volume Two of the Living in a Magical World series) Learning From the Ancestors (Volume Three of the Living in a Magical World series) Everything is Change (Volume Four of the Living in a Magical World series) Living in a Magical World: Volume Five Enchantment is All About Us BeatriceWalditch Heart of Albion Enchantment is All About Us Beatrice Walditch ISBN978-1-905646-29-6 © Text copyright Beatrice Walditch2016 © illustrations copyright contributors 2016 minor revisions 2020 Front cover: Midwinter sunrise, Avebury, 2015. The moral rights of the author and illustrators have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior written permission from Heart of Albion, except for brief passages quoted in reviews. -

Gyn/Ecology the Metaethics of Radical Feminism

GYN/ECOLOGY THE METAETHICS OF RADICAL FEMINISM MARY DALY Beacon Press : Boston : 1978 N.B. Transcript omits footnotes and citations. PREFACE This book voyages beyond Beyond God the Father. It is not that I basically disagree with the ideas expressed there. I am still its author, and thus the situation is not comparable to that of The Church and the Second Sex, whose (1968) author I regard as a reformist foresister, and whose work I respectfully refute in the New Feminist Postchristian Introduction to the 1975 edition. Going beyond Beyond God the Father involves two things. First, there is the fact that be-ing continues. Be-ing at home on the road means continuing to Journey. This book continues to Spin on, in other directions/dimensions. It focuses beyond christianity in Other ways. Second, there is some old semantic baggage to be discarded so that Journeyers will be unencumbered by malfunctioning (male-functioning) equipment. There are some words which appeared to be adequate in the early seventies, which feminists later discovered to be false words. Three such words in BGTF which I cannot use again are God, androgyny, and homosexuality. There is no way to remove male/masculine imagery from God. Thus, when writing/speaking “anthropomorphically” of ultimate reality, of the divine spark of be-ing, I now choose to write/speak gynomorphically. I do so because God represents the necrophilia of patriarchy, whereas Goddess affirms the life-loving be-ing of women and nature. The second semantic abomination, androgyny, is a confusing term which I sometimes used in attempting to describe integrity of be-ing. -

Nothing Is Scarier Than a COBRA Audit by Juli Hanshaw

Nothing Is Scarier Than A COBRA Audit By Juli Hanshaw Halloween brings to mind images of scary • A copy of any invoices mailed for things like ghosts and goblins. However, COBRA coverage nothing can compare to the fear that COBRA • A copy of group health plan documents administrators feel when they hear the words, and summary plan descriptions “COBRA audit.” • Any information on past or pending Some may wish a COBRA audit could be Juli Hanshaw has lawsuits for COBRA obligations a rare, paranormal experience, but as a result more than 15 years • Documentation of notices that were of experience with of revised audit guidelines from the IRS, COBRA and works chances of the COBRA Reaper showing up mailed, including proof of mailing directly for the president for noncompliant employers have increased • Documentation of all COBRA dates, of Infinisource, Inc., which provides payroll, significantly, along with the possibility of such as employment termination and penalties. COBRA, flexible benefit COBRA termination of coverage and other administrative services to more than Earlier this year, the IRS published a • Documentation of COBRA procedural guide, “Audit Techniques and Tax Law to Ex- 17,000 employers updates nationwide. amine COBRA Cases (Continuation of Em- ployee Health Care Coverage),” designed to • Health plan enrollment package, ensure that employers comply with COBRA including notices and disclosures by providing standards that IRS investigators provided to employees at the time of can use for a COBRA audit. (See the Guide, enrollment (for example, the COBRA ¶1373.) general notice) Potentially, a COBRA audit can be like • Information on any wellness programs a haunted house where a company’s profits offered by the plan that might be sub- disappear after an unreported COBRA failure ject to COBRA is detected. -

Decipher the Canticles of the Yuletide Season

Decipher the Canticles of the Yuletide Season These are all popular Christmas songs… put in other words that has the SAME MEANING as the original title. See if you can figure them out! Good Luck! 1. Oh, Member of the Round Table with Missing Areas 2. Boulder of the Tinkling Metal Spheres 3. Vehicular Homicide was Committed on Dad’s mom by a Precipitous Darling 4. Wanted in December: Top Forward Incisors 5. The Apartment of Two Psychiatrists 6. The Lad is a Diminutive Percussionist 7. Sir Lancelot with Laryngitis 8. Decorate the Hallways 9. Cup Shaped Instruments Fashioned of a Whitish Metallic Element 10. Oh Small Israeli Urban Center 11. Farr Off in a Hay bin 12. We are Kong, Lear and Nat Cole 13. May the Deity Bestow an Absence of Fatigue to Mild Male Humans 14. Duodecimal Enumeration of the Passage of the Yuletide Season 15. Leave the Broadcast from an Elevation 16. Our Fervent Hope is that You thoroughly Enjoy Your Yuletide Season 17. Listen, the Winged Heavenly Messengers Are Proclaiming Tunefully 18. As the Guardians of the Wooly Animals Protected Their Charges in the Dark Hours 19. I Beheld a Trio of Nautical Vessels Moving in This Direction 20. Jubilation to the Entire Terrestrial Globe 21. Do you Perceive the Same Vibrations Which Stimulate My Auditory Sense Organs? 22. A Joyful Song of Reverence to Hollow Metallic Vessels Which Vibrate and Bring Forth a Ringing Sound When Struck 23. Parent Was Observed Osculating a Red-Coated Unshaven Teamster 24. An Event Which Arrived on a Cloudless Witching Hour 25. -

Nina Sadur's Portrait by Mikhail Kopyov, Reproduced by the Artist's Permission

NiNa The Witching Hour and Sadur Other Plays Edited by Nadya L. PEtErsoN BostoN 2 0 1 4 Copyright © 2014 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-398-6 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-61811-399-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-61811-400-6 (electronic) Book design by Ivan Grave On the cover: Nina Sadur's portrait by Mikhail Kopyov, reproduced by the artist's permission. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2014 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com C o n t e n t s Acknowledgments ~ 4 ~ Introduction. Nina Sadur’s Fantastic Theater, by Mark Lipovetsky translated by Nadya L. Peterson ~ 6 ~ Go! translated by Nadya L. -

Witch Hunting CWDS Library Reading Lists Series; 13

Witch Hunting CWDS Library Reading Lists Series; 13 Witch Hunting May 2009 Centre for Women’s Development Studies 25 Bhai Vir Singh Marg (Gole Market) New Delhi – 110 001. India. Phones: 91-11-23345530; 23365541; 23366931 - Fax: 91-11-23346044 Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] Website: www.cwds.ac.in/Library/library.html 1 Part I Books, Mimeo Papers/ Reports and Conferences/ Seminars/ Workshops Papers/ Reports 2 001 Barman, Mita Persecution of women: widows and witches p.171-172 IN Women in difficult circumstances: summaries of research.- New Delhi: The Institute,2008. xvi, 202p. 364.153 NAT.W 12310 002 Bosu Mullick, Samar Gender relations and witches among the indigenous communities of Jharkhand, India p. 119-146 IN Gender relations in forest societies in Asia: patriarchy at odds/ed. by Govind Kelkar, Dev Nathan and Pierre Walter. - New Delhi: Sage,2003. 325p. 333.7(5)GEN 10902 003 Bitiya Murmoo Jharkhand mein mahila-hatya ki ek sajish: dayan-pratha p. 66-69 IN Jharkhand ki mahilaein/ed. by Renu Dewan. - Patna: The Academy,2004. iv, 126p. 305.42(5412)BIH.J 12173 004 Carrin, Marine Women, adivasis, subalterns: perspectives on the empowerment of Santals women p. 281-301 IN Recent studies on Indian women: empirical work of social scientists/ed. by Kamal K. Misra and Janet Huber Lowry. - Jaipur: Rawat,2007. vi, 461p. 305.422 REC 11854 005 Chatterji, Jyotsna Challenging witchcraft and cultural and custody practices p. 227-234 IN Living death: trauma of widowhood in India/ed. by V. Mohini Giri. - New Delhi: Gyan,2002. -

Happy-Halloween.Pdf

The New Inquiry Magazine thenewinquiry.com Volume 21 • October, 2013 the new inquiry magazine is licensed under a creative commons license [cc-by-nc-nd 3.0] De Natura animalium, Cambrai ca. 1270 Lampadaire funéraire, Cabaret du Néant Sergius Hruby, Die Muskete, 1933 Ellsworth Kelly, Avocado, 1967 Witchcraft ’70, 1970 Blood on Satan’s Claw, 1971 Night of Dark Shadows, 1971 Virgin Witch, 1972 Editor-in-Chief Rachel Rosenfelt Creative Director Imp Kerr Executive Editor Rob Horning Senior Editors Emily Cooke, Malcolm Harris Managing Editor Joseph Barkeley Editors Atossa A. Abrahamian, Adrian Chen, Max Fox, Samantha Hinds, Sarah Leonard, Willie Osterweil Associate Editors Tim Barker, Erwin Montgomery Editors at Large Aaron Bady, Maryam Monalisa Gharavi, Laurie Penny Contributing Editors Elizabeth Greenwood, Nathan Jurgenson, Sarah Nicole Prickett, Ayesha A. Siddiqi Arts Editor at Large Jesse Darling A/V Editor Michelle Groskopf Special Projects Natasha Lennard, John McElwee Business and Development Will Canine Reader and Advisor Michael Seidenberg Founding Editors Rachel Rosenfelt, Jennifer Bernstein, Mary Borkowski Celluloid Coven edited by Fiona Duncan, 8 Why Witches Can’t Have It All by Durga Chew-Bose, 16 Devils in Red Dress by Moira Weigel, 21 Haunted House by Nic Cavell, 30 Portrait of an Iranian Witch by Alireza Doostdar, 36 The Dark Art of Glamour by Autumn Whitefield-Madrano, 44 Hex Before Marriage by Christine Baumgarthurber, 49 Storefront Supernatural by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio, 54 The Last Witch Hunterby Colin Dickey, 59 News