Digging up Britain Mike Pitts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Kaylor-Smeltzer Genealogy

Some Kaylor-Smeltzer Genealogy Two years ago, while attempting once more to extend some of the family King William I (the Conqueror) tree, I found some web-based sources that yielded quite unanticipated break- 1028 – 1087 King Henry I (Henry Beauclerc) throughs. The family involved was Estep – my grandmother Cline’s family. 1068 – 1135 Since they were Mennonites, I had fallaciously assumed that this was a Ger- Empress Matilda (Lady of the English) man family and that they had arrived in Pennsylvania in the 1730-1770 pe- 1102 – 1167 King Henry II (Curtmantle) riod – the first wave of German immigration. I was wrong on three fronts: 1133 – 1189 the family was English, had arrived much earlier, and came to Maryland. As King John (John Lackland) of this moment, I have found quite a few ancestors. But quite unexpectedly, 1166 – 1216 I found very similar results with the Smeltzer family: it had intermarried in King Henry III (Henry of Winchester) 1207 – 1272 Maryland with English and that led to many discoveries. I am still progress- King Edward I (Longshanks) ing on this but I have already entered nearly 22,000 names of our direct 1239 – 1307 ancestors – and maybe a hundred children of these direct ancestors. (Every- King Edward II 1284 – 1327 one discussed in this message is a direct ancestor.) In the process, I found King Edward III Vikings and Visigoths, Popes and peasants, people who were sainted and peo- 1312 – 1401 ple who were skinned alive. As an example, at right, I present the descent Duke Edmund of Langley from William “the Conqueror” to our grand-mother. -

Purgatoire Saint Patrice, Short Metrical Chronicle, Fouke Le Fitz Waryn, and King Horn

ROMANCES COPIED BY THE LUDLOW SCRIBE: PURGATOIRE SAINT PATRICE, SHORT METRICAL CHRONICLE, FOUKE LE FITZ WARYN, AND KING HORN A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Catherine A. Rock May 2008 Dissertation written by Catherine A. Rock B. A., University of Akron, 1981 B. A., University of Akron, 1982 B. M., University of Akron, 1982 M. I. B. S., University of South Carolina, 1988 M. A. Kent State University, 1991 M. A. Kent State University, 1998 Ph. D., Kent State University, 2008 Approved by ___________________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Susanna Fein ___________________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Don-John Dugas ___________________________________ Kristen Figg ___________________________________ David Raybin ___________________________________ Isolde Thyret Accepted by ___________________________________, Chair, Department of English Ronald J. Corthell ___________________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Jerry Feezel ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………viii Chapter I. Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 Significance of the Topic…………………………………………………..2 Survey of the State of the Field……………………………………………5 Manuscript Studies: 13th-14th C. England………………………...5 Scribal Studies: 13th-14th C. England……………………………13 The Ludlow Scribe of Harley 2253……………………………...19 British Library -

Emma of Normandy, Urraca of León-Castile and Teresa of Portugal

Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras The power of the Genitrix - Gender, legitimacy and lineage: Emma of Normandy, Urraca of León-Castile and Teresa of Portugal Ana de Fátima Durão Correia Tese orientada pela Profª Doutora Ana Maria S.A. Rodrigues, especialmente elaborada para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em História do Género 2015 Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………. 3-4 Resumo............................................................................................................... 5 Abstract............................................................................................................. 6 Abbreviations......................................................................................................7 Introduction………………………………………………………………..….. 8-20 Chapter 1: Three queens, three lives.................................................................21 -44 1.1-Emma of Normandy………………………………………………....... 21-33 1-2-Urraca of León-Castile......................................................................... 34-39 1.3-Teresa of Portugal................................................................................. 39- 44 Chapter 2: Queen – the multiplicity of a title…………………………....… 45 – 88 2.1 – Emma, “the Lady”........................................................................... 47 – 67 2.2 – Urraca, regina and imperatrix.......................................................... 68 – 81 2.3 – Teresa of Portugal and her path until regina..................................... 81 – 88 Chapter 3: Image -

Anglo-Saxon Kings

Who were the famous Anglo Saxon Kings? Who was Alfred the Great? • https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zxsbcdm/articles/z9tdq6f Edward The Elder Ruled899 – 924 • King Edward was well trained by his father, Alfred the Great. • He was a bold soldier who won large portions of land from the Danes in the east and the north. • Much of his success was thanks to the help of his sister, the mighty Aethelflaed. • Edward set up his court in the city of Winchester and built a fine cathedral there. He was married three times and had at least fourteen children. • Some say he was a great supporter of the Church. Others say he was scolded by the Pope for neglecting his faith. • Edward died as he would have wished - at the head of his army, leading his men into battle against a band of rebels. He was laid to rest in his new cathedral at Winchester. Athelstan Ruled 924 - 939 • Athelstan was a daring soldier who fought many battles. But his greatest triumph was the Battle of Brunanburh, when he was faced with an army of Scots and Welsh and Danes. • After this great victory, he seized control of York - the last of the Viking strongholds. Then he forced the kings of Scotland and Wales to pay him large sums of money. • Athelstan wasn't just a soldier. He worked hard to make his kingdom strong, writing laws and encouraging trade. • Athelstan was buried at Malmesbury. At the time of his death he was recognised as the very first King of All England. -

St. Edward the Martyr Catholic.Net

St. Edward the Martyr Catholic.net Edward the Martyr (Old English: Eadweard; c. 962 – 18 March 978) was King of England from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar the Peaceful but was not his father's acknowledged heir. On Edgar's death, the leadership of England was contested, with some supporting Edward's claim to be king and others supporting his much younger half-brother Æthelred the Unready, recognized as a legitimate son of Edgar. Edward was chosen as king and was crowned by his main clerical supporters, the archbishops Dunstan and Oswald of Worcester. The great nobles of the kingdom, ealdormen Ælfhere and Æthelwine, quarrelled, and civil war almost broke out. In the so-called anti-monastic reaction, the nobles took advantage of Edward's weakness to dispossess the Benedictine reformed monasteries of lands and other properties that King Edgar had granted to them. Edward's short reign was brought to an end by his murder at Corfe Castle in 978 in circumstances that are not altogether clear. His body was reburied with great ceremony at Shaftesbury Abbey early in 979. In 1001 Edward's remains were moved to a more prominent place in the abbey, probably with the blessing of his half-brother King Æthelred. Edward was already reckoned a saint by this time. A number of lives of Edward were written in the centuries following his death in which he was portrayed as a martyr, generally seen as a victim of the Queen Dowager Ælfthryth, mother of Æthelred. -

Converted by Filemerlin

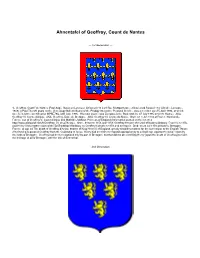

Ahnentafel of Geoffroy, Count de Nantes --- 1st Generation --- 1. Geoffroy, Count1 de Nantes (Paul Augé, Nouveau Larousse Universel (13 à 21 Rue Montparnasse et Boulevard Raspail 114: Librairie Larousse, 1948).) (Paul Theroff, posts on the Genealogy Bulletin Board of the Prodigy Interactive Personal Service, was a member as of 5 April 1994, at which time he held the identification MPSE79A, until July, 1996. His main source was Europaseische Stammtafeln, 07 July 1995 at 00:30 Hours.). AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte d'Anjou. AKA: Geoffroy, Duke de Bretagne. AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte du Maine. Born: on 3 Jun 1134 at Rouen, Normandie, France, son of Geoffroy V, Count d'Anjou and Mathilde=Mahaut, Princess of England (Information posted on the Internet, http://www.wikiwand.com/fr/Geoffroy_VI_d%27Anjou.). Note - between 1156 and 1158: Geoffroy became the Lord of Nantes (Brittany, France) in 1156, and Henry II his brother claimed the overlordship of Brittany on Geoffrey's death in 1158 and overran it. Died: on 26 Jul 1158 at Nantes, Bretagne, France, at age 24 The death of Geoffroy d'Anjou, brother of King Henry II of England, greatly simplifies matters for the succession to the English Throne. After having separated Geoffroy from the Countship of Anjou, Henry had sent him to respond appropriatetly to a challenge against the ducal crown by the lords of Bretagne. Geoffroy had been recognized only by part of Bretagne, but that did not prevent King Henry [upon the death of Geoffroy] to claim the heritage of all of Bretagne, with the title of Seneschal. --- 2nd Generation --- Coat of Arm associated with Geoffroy V, Comte d'Anjou. -

House of Wessex Statistics

House of Wessex Statistics A Grouped Bar Chart to Show Information About the House of Wessex Monarchs 40 30 20 Years 10 0 Alfred the Great Alfred the Elder Edward Æthelstan Edmund I Eadred Eadwig the Peaceful Edgar the Martyr Edward Unready the Æthelred Edmund Ironside the Confessor Edward Monarch Length of Reign Age When They Became Monarch Page 1 of 2 visit twinkl.com House of Wessex Statistics Questions 1. Who reigned for the most years? 2. Who became monarch at the oldest age? 3. Who reigned for 16 years? 4. Who became king at the age of 23? 5. Who reigned for 17 years longer than Edmund I? 6. How many more years did Edward the Elder reign for than Alfred the Great? 7. What is the difference between the youngest and oldest ages of becoming king? 8. Which monarch was twice as old as Eadwig when they became king? 9. How many years did the House of Wessex reign for in total? 10. How old was Edward the Confessor at the end of his reign? Page 2 of 2 visit twinkl.com House of Wessex Statistics Answers 1. Who reigned for the most years? Æthelred the Unready 2. Who became monarch at the oldest age? Alfred the Great 3. Who reigned for 16 years? Edgar the Peaceful 4. Who became king at the age of 23? Eadred 5. Who reigned for 17 years longer than Edmund I? Edward the Confessor 6. How many more years did Edward the Elder reign for than Alfred the Great? 12 years 7. -

Selected Ancestors of the Chicago Rodger's

\ t11- r;$1,--ff" :fi-',v--q-: o**-o* *-^ "n*o"q "I-- 'Ita^!cad$l r.rt.H ls $urq1 uodi uoFour) puE au^l ete)S d-- u.uicnv ls 000'988'Z: I reJo+ uodn oi*cflaN llrprPa srE " 'sauepuno8 laqlo n =-^-Jtos,or lluunspue0NvrulsflnHlu0N -'- 'NVeU0nvt! 0twr0t ---" """ 'salrepuno8 rluno3 i ,- e s(llv1st leNNVtrc sr3tm3 a^nPnsu upr aqt 3'NVEI -__-,,sau?puno6leuorlPL.arLt ] tsF s!-d: ' 6@I Si' Wales and England of Map 508 409 8597 409 508 pue puel0L rrsl'19N9 salen om [email protected] -uv*t' please contact David Anderson at: Anderson David contact please 1,N For additional information, additional For + N 'r'oo"' lojr!rB "tA^ .*eq\M ""t \uir - s ,s *'E?#'lj:::",,X. ."i",i"eg"'. Wo, r rii': Fl?",:ll.jl,r ,s *,,^ . l"lfl"'" 1SVo! s.p, ;eG-li? ol.$q .:'N" avl r'/ !',u l.ltll:,wa1 H'. P " o r l\);t; !ff " -oNv P-9 . \ . ouorrufq 6 s 'dM .ip!que3 /,.Eer,oild.,.r-ore' uot-"'j SIMOd ) .,,i^.0'"i'"'.=-1- 4.1 ...;:,':J f UIHS i";,.i*,.relq*r -l'au8.rs.rd1'* tlodtiod * 1- /I!!orq8,u! l&l'p4.8 .tr' \ Q '-' \ +lr1: -/;la-i*iotls +p^ .) fl:Byl''uo$!eH l''",,ili"l,"f \ ,uoppor .q3norcq.trrv i ao3!ptDj A rarre;'a\ RUPqpuou^M. L,.rled. diulMoo / ) n r".c14!k " *'!,*j ! 8il5 ^ris!€i<6l-;"qrlds qteqsu uiraoos' \u,.".',"u","on". ' \. J$Pru2rl 3rEleril. I ubFu isiS. i'i. ,,./ rurHSNtoiNll AM-l' r- 'utqlnx i optow tstuuqlt'" %,.-^,r1, ;i^ d;l;:"f vgs "".'P"r;""; --i'j *;;3,1;5lt:r*t*:*:::* HTVON *",3 r. -

The Stones of Cumbria

The Stones of Cumbria by Amy R. Miller A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Amy R. Miller 2012 The Stones of Cumbria Amy R. Miller Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Gosforth, in the English province of Cumbria, is home to a group of tenth-century sculptures that are among the most intricate and best-preserved examples of Anglo-Scandinavian monumental stone carving. These sculptures are essential for appreciating the complex and rich culture that developed in the late first millennium in northern England. This thesis offers a detailed analysis of the Gosforth sculptural group through multiple facets of its construction, design, and location to gain a broader understanding of the role of public sculpture in the unsettled but dynamic regions of Viking England. The complexity of Anglo-Scandinavian sculpture is examined first through an archaeological and material reassessment that reveals the method of the monuments’ construction and further supports the attribution for most of the sculptures to a single artist, whose craftsmanship, composition, and style match works across northern England, several of which were previously unattributed to him. This corpus expands our understanding of at least one professional early medieval artist and enables us to refine the general timeline of sculptural production in England. This artist sculpted in support of a new Anglo-Scandinavian elite, who adopted the local practice of ornamenting carved crosses but consciously adapted the ii iconography to reflect and reaffirm their otherness. By referencing one another, the sculptures forged and reflected the complex process of mutual acculturation and competition among communities and served as fixed spatial and mental foci in the Viking Age settlement of northern England. -

Download Free At

People, texts and artefacts Cultural transmission in the medieval Norman worlds People, texts and artefacts Cultural transmission in the medieval Norman worlds Edited by David Bates, Edoardo D’Angelo and Elisabeth van Houts LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WCE HU First published in print in (ISBN ----) is book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives . International (CC BY- NCND .) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN ---- (PDF edition) DOI: ./. Contents Editors’ preface vii List of contributors ix List of plates and gures xiii Abbreviations xv Introduction 1 David Bates and Elisabeth van Houts . Harness pendants and the rise of armory 17 John Baker . e transmission of medical culture in the Norman worlds c.1050–c.1250 47 Elma Brenner . Towards a critical edition of Petrus de Ebulo’s De Balneis Puteolanis: new hypotheses 65 Teolo De Angelis . A Latin school in the Norman principality of Antioch 77 Edoardo D’Angelo 5. Culti e agiograe d’età normanna in Italia meridionale 89 Amalia Galdi . e landscape of Anglo-Norman England: chronology and cultural transmission 105 Robert Liddiard . e medieval archives of the abbey of S. Trinità, Cava 127 G. A. Loud . Écrire la conquête: une comparaison des récits de Guillaume de Poitiers et de Georoi Malaterra 153 Marie-Agnès Lucas-Avenel . Bede’s legacy in William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon 171 Alheydis Plassmann v People, texts and artefacts: cultural transmission in the medieval Norman worlds . -

Alfred the Great George IV Charles I Edward IV Cnut the Great Edward

British Monarchs Alfred the Great Edward the Elder Athelstan Edmund I Eadred Eadwig Edgar the Peaceful Edward the Martyr Ethelred the Unready Edmund Ironside Reign: c.886 – Reign: 26th October 899 Reign: c.924 – Reign: 27th October 939 Reign: 26th May 946 – Reign: 23rd November Reign: 1st October 959 Reign: 8th July 975 – Reign: 18th March 978 Reign: 23rd April 1016 26th October 899 – 17th July 924 27th October 939 – 26th May 946 23rd November 955 955 – 1st October 959 – 8th July 975 18th March 978 – 23rd April 1016 – 30th November 1016 William the Conqueror William II Henry I Stephen Cnut the Great Harold I Harthacnut Edward the Confessor Harold Godwinson (William I) (William Rufus) (Henry Beauclerc) (Stephen of Blois) Henry II Reign: 18th October 1016 Reign: 12th November Reign: 17th March Reign: 8th June 1042 Reign: 6th January 1066 Reign: 25th December 1066 Reign: 26th September Reign: 5th August 1100 – Reign: 22nd December Reign: 19th December – 12th November 1035 1035 – 17th March 1040 1040 – 8th June 1042 – 5th January 1066 – 14th October 1066 – 9th September 1087 1087 – 2nd August 1100 1st December 1135 1135 – 25th October 1154 1154 – 6th July 1189 Richard I Henry VI Reign: (1st) 1st September (Richard the Lionheart) John Henry III Edward I Edward II Edward III Richard II Henry IV Henry V 1422 – 4th March 1461 Reign: 3rd September 1189 Reign: 27th May 1199 – Reign: 28th October 1216 Reign: 20th November Reign: 8th July 1307 – Reign: 25th January Reign: 22nd June 1377 Reign: 30th September Reign: 21st March 1413 (2nd) 3rd October -

The Viking Invasion of Britain for Thousands of Years, Britain Has Been Invaded by Stronger Nations

The Viking invasion of Britain For thousands of years, Britain has been invaded by stronger nations. One of the most famous being the Roman invasion of Britain until AD 401. When the Romans left, the Anglo Saxons settled in Britain and ruled until the Vikings from Scandanavia made their way across the sea to invade and settle in Britain. They were a stronger nation than England were at that time and were able to establish themselves within England and other parts of Britain. The First Britons The Anglo Saxons in Britain From around AD400 onwards, Anglo-Saxons settled in villages next to their farmland. They set up a number of different kingdoms, led by lords and chieftains. The most powerful lords acted like local kings and fought one another to gain more land. The strongest Anglo-Saxon tribal chiefs were known as Bretwalda or ‘Ruler of Britain’. By AD800, most Anglo-Saxons had converted to Christianity, and merchants traded goods all over the country and into Europe, making some Anglo-Saxon kingdoms very wealthy. The Vikings in Britain In the mid-700s, the people of Scandinavia (Norway, Denmark and Sweden) began to explore, raid and eventually invade the countries around them. They sailed to Britain, Ireland, France, Spain and Italy. Others travelled by land, going as far as Israel, Greenland and probably America. They were known as Vikings, or Northmen, and began their raids on Britain around the AD790S. The Vikings attacked Britain because they had traded goods with the Anglo- Saxons for many years, and knew of their wealth.