Socio-Cultural Backgrounds of Japanese Interpersonal Communication Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Off the Beaten Track: Women's Sport in Iran, Please Visit Smallmedia.Org.Uk Table of Contents

OFF THE BEATEN TRACK: WOMEn’s SPORT IN IRAN Islamic women’s sport appears to be a contradiction in terms - at least this is what many in the West believe. … In this respect the portrayal of the development and the current situation of women’s sports in Iran is illuminating for a variety of reasons. It demonstrates both the opportunities and the limits of women in a country in which Islam and sport are not contradictions.1 – Gertrud Pfister – As the London 2012 Olympics approached, issues of women athletes from Muslim majority countries were splashed across the headlines. When the Iranian women’s football team was disqualified from an Olympic qualifying match because their hejab did not conform to the uniform code, Small Media began researching the history, structure and representation of women’s sport in Iran. THIS ZINE PROVIDES A glimpsE INto THE sitUatioN OF womEN’S spoRts IN IRAN AND IRANIAN womEN atHLETES. We feature the Iranian sportswomen who competed in the London 2012 Summer Olympics and Paralympics, and explore how the western media addresses the topic of Muslim women athletes. Of course, we had to ground their stories in context, and before exploring the contemporary situation, we give an overview of women’s sport in Iran in the pre- and post- revolution eras. For more information or to purchase additional copies of Off the Beaten Track: Women's Sport in Iran, please visit smallmedia.org.uk TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Historical Background 5 Early Sporting in Iran 6 The Pahlavi Dynasty and Women’s Sport 6 Women’s Sport -

Asia's Olympic

Official Newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia Edition 51 - December 2020 ALL SET FOR SHANTOU MEET THE MASCOT FOR AYG 2021 OCA Games Update OCA Commi�ee News OCA Women in Sport OCA Sports Diary Contents Inside Sporting Asia Edition 51 – December 2020 3 President’s Message 10 4 – 9 Six pages of NOC News in Pictures 10 – 12 Inside the OCA 13 – 14 OCA Games Update: Sanya 2020, Shantou 2021 15 – 26 Countdown to 19th Asian Games 13 16 – 17 Two years to go to Hangzhou 2022 18 Geely Auto chairs sponsor club 19 Sport Climbing’s rock-solid venue 20 – 21 59 Pictograms in 40 sports 22 A ‘smart’ Asian Games 27 23 Hangzhou 2022 launches official magazine 24 – 25 Photo Gallery from countdown celebrations 26 Hi, Asian Games! 27 Asia’s Olympic Era: Tokyo 2020, Beijing 2022 31 28 – 31 Women in Sport 32 – 33 Road to Tokyo 2020 34 – 37 Obituary 38 News in Brief 33 39 OCA Sports Diary 40 Hangzhou 2022 Harmony of Colours OCA Sponsors’ Club * Page 02 President’s Message OCA HAS BIG ROLE TO PLAY IN OLYMPIC MOVEMENT’S RECOVERY IN 2021 Sporting Asia is the official newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia, published quarterly. Executive Editor / Director General Husain Al-Musallam [email protected] Director, Int’l & NOC Relations Vinod Tiwari [email protected] Director, Asian Games Department Haider A. Farman [email protected] Editor Despite the difficult circumstances we Through our online meetings with the Jeremy Walker [email protected] have found ourselves in over the past few games organising committees over the past months, the spirit and professionalism of our few weeks, the OCA can feel the pride Executive Secretary Asian sports family has really shone behind the scenes and also appreciate the Nayaf Sraj through. -

Fishing and Early Jomon Foodways at Sannai Maruyama, Japan

Fishing and Early Jomon Foodways at Sannai Maruyama, Japan By Mio Katayama A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Junko Habu, Chair Professor Christine Hastorf Professor Mack Horton Spring 2011 Abstract Fishing and Early Jomon Foodways at Sannai Maruyama, Japan By Mio Katayama Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Junko Habu, Chair This thesis examines the economic vs. social and symbolic importance of fish in the foodways of the prehistoric Jomon culture (16,000-2300 cal BP) of Japan. To achieve this goal, quantitative analyses of fish remains excavated from a water-logged midden of the Sannai Maruyama site (Aomori Prefecture, Japan) are conducted. Dated to the Lower Ento–a phase (ca. 5900–5650 cal BP) of the Early Jomon Period, the midden was associated with large amounts of organic remains, including fish bones. The perspective employed in this dissertation, foodways, emphasizes the importance of social and cultural roles of food. Rather than focus on bio-ecological aspects and nutritional values of food, this thesis regards food as one of the central elements of individual cultures. In Japanese archaeology, food of the Jomon Period has been a central them to the discussion reconstructing the lifeways of prehistoric people of the Japanese archipelago. Large amounts of data, including faunal and floral materials, have been accumulated from numerous rescue excavations of Jomon sites that took place between the 1970s and late 1990s. These archaeological data allowed the development of detailed culture historical studies of the Jomon Period that span over 10,000 years. -

Deciphering Bin Salman's Change of Tone

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13932 Saturday MAY 1, 2021 Ordibehesht 11, 1400 Ramadan 18, 1442 Iran closely watching Iran learn fate at Home appliance Claudio Noce’s Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan FIBA U19 Basketball production increases “Padrenostro” to compete border conflict Page 2 World Cup Page 3 by 36% Page 4 in Fajr filmfest Page 8 Dozens ‘crushed to death’ in See page 3 Israel pilgrimage stampede Deciphering A stampede at a religious festival attended will not give up until the last victim by tens of thousands of ultra-Orthodox is evacuated.” Jews in northern Israel has killed at least Zaki Heller, spokesman for the Magen 44 people and injured about 150 early David Adom, said that among the 150 Friday, medical officials said. people who had been hospitalized, six Magen David Adom, the Israeli were in critical condition. bin Salman’s emergency service, said that at least On social media, Benjamin Netanyahu 44 people were killed during the event called it a “heavy disaster” and added: early on Friday, adding “MDA is fighting “We are all praying for the wellbeing of for the lives of dozens wounded, and the casualties.” change of Water, development projects worth over $619m inaugurated TEHRAN - Iranian President Hassan million) in Khuzestan, Mazandaran and Rouhani on Thursday inaugurated three Hormozgan provinces. water supply projects as well as a dam in The projects were inaugurated under tone three provinces through vide conference, the framework of the Energy Ministry’s IRNA reported. -

78-5890 MECHIKOFF, Robert Alan, 1949- the POLITICALIZATION of the XXI OLYMPIAD

78-5890 MECHIKOFF, Robert Alan, 1949- THE POLITICALIZATION OF THE XXI OLYMPIAD. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1977 Education, physical University Microfilms International,Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 © Copyright by Robert Alan Mechikoff 1977 THE POLITICALIZATION OF THE XXI OLYMPIAD DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Alan Mechikoff, B.A., M.A. The Ohio State University 1977 Reading Committee Approved By Seymour Kleinman, Ph.D. Barbara Nelson, Ph.D. Lewis Hess, Ph.D. / Adviser / Schoc/l of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation This study is dedicated to Angela and Kelly Mechikoff; Alex and Aileen Mechikoff; Frank, Theresa, and Anthony Riforgiate; and Bob and Rosemary Steinbauer. Without their help, understanding and encouragement, the completion of this dissertation would not be possible. VITA November 7, 1949........... Born— Whittier, California 1971......................... B.A. , California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach California 1972-1974....................Teacher, Whittier Union High School District, Whittier, California 1975......................... M.A. , California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach, California 1975-197 6 ....................Research Assistant, School of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1976-197 7....................Instructor, Department of Physical Education, University of Minnesota, Duluth, Duluth, Minnesota FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: Physical Education Studies in Philosophy of Sport and Physical Education. Professor Seymour Kleinman Studies in History of Sport and Physical Education. Professor Bruce L. Bennett Studies in Administration of Physical Education. Professor Lewis A. Hess TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................... iii VITA........................................................ iv Chapter I. -

Vb W Previous Ag

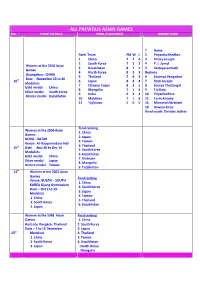

ALL PREVIOUS ASIAN GAMES No. EVENT DETAILS FINAL STANDINGS INDIAN TEAM ? Name Rank Team Pld W L 2 Priyanka Khedkar 1 China 7 7 0 3 Princy Joseph 2 South Korea 7 5 2 4 P. J. Jomol Women at the 2010 Asian 3 Kazakhstan 8 7 1 5 Kattuparambath Games 4 North Korea 8 5 3 Reshma Guangzhou - CHINA 5 Thailand 7 4 3 6 Soumya Vengadan Date November 13 to 26 16th 6 Japan 8 4 4 7 Shibi Joseph Medalists 7 Chinese Taipei 8 3 5 8 Soorya Thottangal Gold medal China 8 Mongolia 7 1 6 9 Tiji Raju Silver medal South Korea 9 India 6 2 4 10 Priyanka Bora Bronze medal Kazakhstan 10 Maldives 7 1 6 12 Terin Antony 11 Tajikistan 5 0 5 16 Minomol Abraham 18 Aswani Kiran Head coach: Devidas Jadhav Final ranking Women at the 2006 Asian 1. China Games 2. Japan DOHA - QATAR 3. Taiwan Venue Al-Rayyan Indoor Hall 4. Thailand 15th Date Nov 26 to Dec 14 5. South Korea Medalists 6. Kazakhstan Gold medal China 7. Vietnam Silver medal Japan 8. Mongolia Bronze medal Taiwan 9. Tadjikistan 14th Women at the 2002 Asian Games Final ranking Venue: BUSAN – SOUTH 1. China KOREA Gijang Gymnasium 2. South Korea Date :- Oct 2 to 13 3. Japan Medalists 4. Taiwan 1 China 5. Thailand 2 South Korea 6. Kazakhstan 3 Japan Women at the 1998 Asian Final ranking Games 1. China Host city Bangkok, Thailand 2. South Korea Date :- 7 to 15 December 3. Japan 13th Medalists 4. -

Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Chiavacci, (eds) Grano & Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia East Democratic in State the and Society Civil Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. Books in the series typically combine theory with empirical research, dealing with various types of mobilization, from neighborhood groups to revolutions. We especially welcome work that synthesizes or compares different approaches to social movements, such as cultural and structural traditions, micro- and macro-social, economic and ideal, or qualitative and quantitative. Books in the series will be published in English. One goal is to encourage non- native speakers to introduce their work to Anglophone audiences. Another is to maximize accessibility: all books will be available in open access within a year after printed publication. Series Editors Jan Willem Duyvendak is professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam. James M. Jasper teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Amsterdam University Press Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Final Kietlinski

REVIEW ESSAY The Olympic Games: Showcases of Internationalism and Modernity in Asia Robin Kietlinski, City University of New York – LaGuardia Community College Stefan Huebner. Pan-Asian Sports and the Emergence of Modern Asia, 1913–1974. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2016. 416 pp. $42 (paper). Jessamyn R. Abel. The International Minimum: Creativity and Contradiction in Japan’s Global Engagement, 1933–1964. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2015. 344 pp. $54 (cloth). Over the past two decades, the English-language scholarship on sports in Asia has blossomed. Spurred in part by the announcement in 2001 that Beijing would host the 2008 Summer Olympics, the number of academic symposia, edited volumes, and monographs looking at sports in East Asia from multiple disciplinary perspectives has increased substantially in the twenty- first century. With three Olympic Games forthcoming in East Asia (Pyeongchang 2018, Tokyo 2020, and Beijing 2022), the volume of scholarship on sports, the Olympics, and body culture in this region has continued to grow and to become ever more nuanced. Prior to 2001, very little English-language scholarly work on sports in Asia considered the broader significance of sporting events in East Asian history, societies, and politics (both regional and global). Several recent publications have complicated and contextualized this area of inquiry.1 While some of this recent scholarship makes reference to countries across East Asia, single-author monographs tend to focus on one nation, and particularly on how nationalism and sports fueled each other in the tumultuous twentieth century.2 Scholarship on internationalism in the context of sporting events in East Asia is much harder to come by. -

Obama Eyes Air Strikes in Syria, Fixing Iraqi Army

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2014 THULQADA 16, 1435 AH www.kuwaittimes.net UN honor to BJP head Long tongues, Nishikori loses be shared charged leaping cats US Open, wins with Kuwaiti over hate in 60th World $940,000 bonus people:2 Amir speech13 Records40 book from16 Uniqlo Obama eyes air strikes in Max 44º Min 28º Syria, fixing Iraqi army High Tide 00:28 & 12:29 Kerry vows global coalition will defeat IS Low Tide 06:33 & 19:08 40 PAGES NO: 16282 150 FILS WASHINGTON: US President Barack Obama seemed poised to authorize air strikes against the Islamic State FM to visit in Syria, ahead of a speech to brace his nation for a long duel with the jihadists. In a much -anticipated White House address, Obama was also expected to announce Palestine a plan to rebuild Iraq’s splintered army. He called Saudi King Abdullah, a pivotal member of the coalition he is KUWAIT: Foreign Minister Sheikh Sabah Al-Khaled building to battle IS, and gathered top defense and Al-Sabah will visit the Palestinian territories next intelligence chiefs, while finalizing a strategy for the week for talks on reconciliation among the kind of prolonged new intervention in the Middle East Palestinians, an official said yesterday. The visit will be he has always abhorred. the first by a senior Kuwaiti official since the Officials said Obama was also pressing Congress to Palestinian Authority sign off on $500 million in aid to equip and train “mod- was created two erate” Syrian rebels, who would be on-the-ground part- decades ago. -

P17 Layout 1

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2014 SPORTS ASIAN GAMES Gold glitters for India despite turmoil NEW DELHI: India are seeking a record Asian Games medal haul despite a chaotic build-up, with their jumbo squad slashed at the last minute, their boxers under a cloud and top athletes either South Korea ‘Big injured or opting out. With just 10 days to go, the intended travel- ling party of 942 athletes and officials was cut by nearly a third in Dragon’ chases a cost-saving move which discarded 146 competitors seen as hav- ing little chance of a medal. Separately India’s boxers, led by mul- badminton gold tiple world champion Mary Kom, face the prospect of not being able to fight under the national flag following a row with the International Boxing Association. SEOUL: When your parents give you a name like “Big Star boxer Vijender Singh is out injured, while Olympic medal- Dragon,” chances are they expect great things from winning wrestler Sushil Kumar and India’s number one tennis you. South Korea’s top badminton player Lee Yong-dae player Somdev Devvarman are both concentrating on other com- has not let them down. Lee won the mixed doubles petitions. In a further blow to tennis hopes, doubles specialists crown as a 20-year-old at the 2008 Beijing Olympics Leander Paes, Rohan Bopanna and Sania Mirza were granted per- with Lee Hyo-jung, and a bronze at the 2012 London mission by the All-India Tennis Association on Wednesday to skip Games in men’s doubles with Jung Jae-sung. -

IOC President Praises OCA

Official Newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia Edition 52 - March 2021 WIN-WIN DOHA, RIYADH OCA GENERAL ASSEMBLY NAMES TWO ASIAN GAMES HOST CITIES Inside the OCA | OCA Games Update | NOC News | Women In Sport Contents Inside Sporting Asia Edition 52 – March 2021 3 President’s Message 9 4 – 9 Six pages of NOC News in Pictures 10 – 16 OCA Games Update 10 – 15 19th Asian Games Hangzhou 2022 16 Asian Youth Games Shantou 2021 12 17 – 24 39th OCA General Assembly Muscat 2020 17 OCA President’s welcome message 18 – 19 It’s a win-win situation 20 – 21 Muscat Photo Gallery 23 22 OCA Order of Merit/AYG Tashkent 2025 23 IOC President praises OCA 24 General Assembly Notebook 25 – 27 Inside the OCA 28 28 – 31 Women in Sport 32 – 33 Road to Tokyo 34 – 35 News in Brief 36 – 37 Obituary 38 – 39 OCA Sports Diary 32 40 Hangzhou 2022 OCA Sponsors’ Club * Page 02 President’s Message OCA WILL EMERGE STRONGER FROM PANDEMIC PROBLEMS Sporting Asia is the official newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia, published quarterly. Executive Editor / Director General Husain Al-Musallam [email protected] Director, Int’l & NOC Relations Vinod Tiwari [email protected] Director, Asian Games Department Haider A. Farman [email protected] Editor IT Director t was very disappointing to postpone two This will make it a busy year for our NOCs, Amer Elalami I Jeremy Walker [email protected]@ocasia.org of our OCA games in quick succession. with the Beijing Winter Olympics in Febru- ary, AIMAG 6 in March and our 19th Asian Executive Secretary The 6th Asian Beach Games in Sanya, China Games in Hangzhou, China in September. -

A Deep Pool of Talent >> DOHA GAMES SWIMMING

NOVEMBER 12, 20 CHINA DAILY PAGE 4 ASIAD AQUATICS CHRISTOPHE SIMON / AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE China’s Zhang Lin celebrates after winning the men’s 800m freestyle fi nal in a world record time of 7:32.12 on July 29, 2009 at the FINA World Swimming Championships in Rome. BY THE NUMBERS A deep pool of talent >> DOHA GAMES SWIMMING CHINESE TO GO HEAD TO HEAD WITH JAPAN AND REPUBLIC OF KOREA FOR SWIMMING GLORY 16 By LEI LEI and support of the people. We must Another challenge will come Chinese team is ourselves,” said gold CHINA DAILY beat them, and all of us are confi dent from Beijing Olympic 400m free- team leader Zhou Jihong. “We we can,” Yao said. style gold medalist, ROK’s Park. hope our athletes will do their GUANGZHOU — One of the “We hope the men’s team will Zhang will meet Park — who beat best. If they perform at their best, greatest rivalries at the Guangzhou make a breakthrough and that the him in the 400m by 0.58 seconds to no matter if they win or not, it will Asian Games will be on display in women don’t make mistakes. Let’s win the Olympic gold medal in Bei- be good.” the swimming pool. wait and see how the two teams jing — in the 200m, 400m, 1,500m Since fi rst taking part in the div- 21 The Chinese team will face a perform at the competition.” and 4x200m relay. ing events at the 1974 Asian Games, silver strong challenge from neighboring The Chinese team comprises On the women’s side, world the Chinese team has swept all the Japan, while China’s leading swim- a mixture of veterans and young champion Liu Zige will be absent, gold medals in the sport.