An Introduction to Traditional Building Materials and Practices Elizabeth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thornhill House, Longmorn, Elgin, Moray

THORNHILL HOUSE LONGMORN, ELGIN, MORAY THORNHILL HOUSE, LONGMORN, ELGIN, MORAY. An outstanding family home in a scenic rural setting Elgin 3 miles ■ Inverness 32 miles ■ Aberdeen 63 miles 3.43 acres (1.39 hectares) ■ 2 reception rooms, 4 bedrooms. ■ Flexible accommodation ■ Traditional steading and walled garden ■ 2 useful paddocks ■ Stunning views over the Laich o’ Moray and surrounding countryside ■ Tranquil yet very accessible position Elgin 01343 546362 [email protected] SITUATION Thornhill is an impressive and most attractive family home located in a secluded and yet easily accessible rural setting about 3 miles from the centre of Elgin. Elgin (about 3 miles) provides a comprehensive range of shops and amenities including various large supermarkets, a cinema, leisure centre and hospital whilst the surrounding area offers some excellent hotels, restaurants and historic local attractions. Elgin has schooling to secondary level whilst Gordonstoun Independent School is about 10 miles away. Inverness (about 41 miles) has all the facilities of a modern city including an airport which can be reached in just under an hour’s drive offering regular flights to the south and summer flights to many European destinations. A greater variety of flight destinations is available from Aberdeen Airport (about 56 miles). Elgin railway station has regular services to Inverness and Aberdeen. The county of Moray is famous for its mild climate, has a beautiful and varied countryside with a coastline of rich agricultural land, prosperous fishing villages and wide, open beaches. The upland areas to the South are sparsely populated and provide dramatic scenery, some of which forms the Cairngorm National Park. -

March Road, Rathven, Buckie, AB56 4BS Written Scheme of Investigation (WSI)

March Road, Rathven, Buckie, AB56 4BS Written Scheme of Investigation (WSI) National Grid Reference: NJ43963 65460 Parish: Rathven Height OD: 30-45m OD Written and researched by: Cameron Archaeology Commissioning client: Moray Council Contractor: Cameron Archaeology 45 View Terrace Aberdeen AB25 2RS 01224 643020 07581 181057 [email protected] www.cameronarchaeology.com Company registration no 372223 (Scotland) VAT registration no 990 4373 00 Date: 28 June 2017 1 BACKGROUND 1.1 The site (Illus 1) is located on the east side of March Road, Rathven south of the junction with Main Road. It is centred on NGR NJ43963 65460, at 30-45m OD in the parish of Rathven. 1.2 The work was commissioned by Moray Council. An application 17/00193/APP to Moray Council for a proposed road development and associated landscaping requires a 5-7% archaeological evaluation. 1.3 All the archaeological work will be carried out in the context of Scottish Planning Policy (SPP) Planning Advice Note (PAN 2/2011) and Historic Environment Scotland's Policy Statement (HESPS) which state that archaeological remains should be regarded as part of the environment to be protected and managed. Illus 1 Location plan (Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2017) CA356 Rathven, Buckie WSI Cameron Archaeology CA356-2017 2 Illus 2 Site plan showing proposed development (copyright Moray Council) CA356 Rathven, Buckie WSI Cameron Archaeology CA356-2017 3 2 ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND 2.1 There is one Scheduled Monument within 1km of the proposed development. Tarrieclerack long cairn is 700m from the southern boundary of the site. The monument comprises a long cairn of prehistoric date, visible as a low mound. -

Of 5 Polling District Polling District Name Polling Place Polling Place Local Government Ward Scottish Parliamentary Cons

Polling Polling District Local Government Scottish Parliamentary Polling Place Polling Place District Name Ward Constituency Houldsworth Institute, MM0101 Dallas Houldsworth Institute 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Dallas, Forres, IV36 2SA Grant Community Centre, MM0102 Rothes Grant Community Centre 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray 46 - 48 New Street, Rothes, AB38 7BJ Boharm Village Hall, MM0103 Boharm Boharm Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Mulben, Keith, AB56 6YH Margach Hall, MM0104 Knockando Margach Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Knockando, Aberlour, AB38 7RX Archiestown Hall, MM0105 Archiestown Archiestown Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray The Square, Archiestown, AB38 7QX Craigellachie Village Hall, MM0106 Craigellachie Craigellachie Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray John Street, Craigellachie, AB38 9SW Drummuir Village Hall, MM0107 Drummuir Drummuir Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Drummuir, Keith, AB55 5JE Fleming Hall, MM0108 Aberlour Fleming Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Queens Road, Aberlour, AB38 9PR Mortlach Memorial Hall, MM0109 Dufftown & Cabrach Mortlach Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Albert Place, Dufftown, AB55 4AY Glenlivet Public Hall, MM0110 Glenlivet Glenlivet Public Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Glenlivet, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EJ Richmond Memorial Hall, MM0111 Tomintoul Richmond Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Tomnabat Lane, Tomintoul, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EZ McBoyle Hall, BM0201 Portknockie McBoyle Hall 2 - Keith and Cullen Banffshire and Buchan Coast Seafield -

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Banffshire, Scotland Fiche and Film

Banffshire Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1861 Census Maps Probate Records 1861 Census Indexes Miscellaneous Taxes 1881 Census Transcript & Index Monumental Inscriptions Wills 1891 Census Index Non-Conformist Records Directories Parish Registers 1861 CENSUS Banffshire Parishes in the 1861 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Aberlour (145) Film BAN 145-152 Craigillachie Charleston Alvah (146) Parliamentary Burgh of Banff Royal Burgh of Banff/Banff Town Film BAN 145-152 Macduff (Parish of Gamrie) Macduff Elgin (or Moray) Banff (147) Film BAN 145-152 Banff Landward Botriphnie (148) Film BAN 145-152 Boyndie (149) Film BAN 145-152 Whitehills Cullen (150) Film BAN 145-152 Deskford (151) Kirkton Ardoch Film BAN 145-152 Milltown Bovey Killoch Enzie (152) Film BAN 145-152 Parish of Fordyce (153) Sandend Fordyce Film BAN 153-160 Portsey Parish of Forglen (154) Film BAN 153-160 Parish of Gamrie (155) Gamrie is on Film 145-152 Gardenstoun Crovie Film BAN 153-160 Protstonhill Middletonhill Town of McDuff Glass (199) (incorporated with Aberdeen Portion of parish on Film 198-213) Film BAN 198-213 Parish of Grange (156) Film BAN 153-160 Parish of Inveravon (157) Film BAN 153-160 Updated 18 August 2018 Page 1 of 6 Banffshire Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1861 CENSUS Continued Parish of Inverkeithny (158) Film BAN 153-160 Parish of Keith (159) Old Keith Keith Film BAN 153-160 New Mill Fifekeith Parish of Kirkmichael (160) Film BAN 153-160 Avonside Tomintoul Marnoch (161) Film BAN 161-167 Marnoch Aberchirder Mortlach (162) Film BAN 161-167 Mortlach Dufftown Ordiquhill (163) Film BAN 161-167 Cornhill Rathven (164) Rathven Netherbuckie Lower Shore of Buckie Buckie New Towny Film BAN 161-167 Buckie Upper Shore Burnmouth of Rathven Peterhaugh Porteasie Findochty Bray Head of Porteasie Rothiemay (165) Film BAN 161-167 Milltown Rothiemay St. -

1 1 1923 Jan 4 Dance

1 1923 Jan 4 Dance - The Rathven, Enzie and Bellie Ploughing association has a new venue for their annual dance. on January 12. In 1921, this had been held at Sauchenbush by kind permission of James Grant, farmer, last year it was held in the Arradoul Smiddy and this year it will take place in the new WRI hall at Arradoul. In addition to the dance a concert will take place. Admission to the concert is 1/3 and admittance to the - Gents 2/- with Ladies 1/- Millers - The Motor and Cycle firm who have a shop on Baron Street opened a new garage at 55 West Church Street. Advertisers - W. J. Smith, 19 Land Street, Ladies and Gents Tailor. Suits and costumes made up from one’s own cloth. Roderick Johnston, 4 Low Street, Painter and Decorator. D. McLachlan Cluny Square, Ford Touring car for £152. A self- starter at £15 not included in the price. Robert Gillan, Wine Merchant and Italian Warehouseman, 9 East Church Street. A. Flett, 26 East Church Street, Lyceum Buildings bought over the whole stock of Ben Calder, Shoemaker and was holding a ‘mammoth’ sale. Big sale at E. Duncan 60 East Church Street. G. Watt, 12 Land Street, Potato Merchant. Murray the shop for sweets - 26 East Church Street. Cooper's Fruit Store is now at 27 High Street. P. Geddes and Sons, Tailors, Bridge Place - Sale. Chemists in Buckie - J. Stewart, 46 West Church Street, Robertson, 3 Bank Street, Gibson, 12 West Church Street and Anderson, 5 High Street. “The Braes of Strathlene, “the name of a song written by Alex Johnston, editor of the B. -

Morayshire Deaths

Morayshire Parish Ref. MI’s, Burial & Death Records Publisher Shelf OPR Death Mark Records Aberlour Aberlour Old Churchyard, New Cemetery & MBGRG TB/BA Parish Church, St Margaret’s Scottish Episcopal Church & Burial Register, Aberlour & Area War Memorials (note: this is a single publication) Alves 125 Alves Chyd & Cemetery ANESFHS TB/BA 1663-1700 Alves Old Chyd MBGRG to FTM Vol 5 TB/BA Alves Churchyard & New cemetery MBGRG vol 5 TB/BA Bellie 126 Bellie, Fochabers Speyside, SGS, pre 1855 TB/BA 1791-1852 Bellie Old Chyd MBGRG, FTM vol 3. TB/BA The Story of the Old Church & Chyd of Bellie B Bishop TB/BA Bellie Chyd & New Cemetery MBGRG TB/BA St Ninians, Tynet MBGRG TB/BA St Ninians (Chapelford) TB/BA Birnie 127 Birnie Chyd ANESFHS, to C20 TB/BA 1722-1769 Birnie New Cemy ANESFHS, to C20 TB/BA Birnie Chyd MBGRG, FTM vol 6 TB/BA Birnie Chyd 18th & 19th century burials MBGRG TB/BA Birnie Chyd & New Cemetery . MBGRG TB/BA Boharm 128A Boharm MI’s MBGRG to C20 TB/BA 1701-1732 Cromdale & 128B Cromdale Speyside, SGS, pre 1855 TB/BA Inverallan Cromdale Churchyard, Badenoch & Strathspey HFHS TB/BA Advie Churchyard MI’s & War Memorial HFHS TB/BA Inverallan CD SMI – CD TB/BA Granton On Spey cemetery HFHS TB/BA TB/BA Dallas 129 Dallas churchyard & War Memorial MBGRG TB/BA 1775-1818 Drainie 130 Kinneddar Chyd ANESFHS, to C20 TB/BA 1703-1853 Kinneddar Chyd MBGRG, FTM vol 3 TB/BA Michael Kirk,Gordonstoun ANESFHS, TB/BA The Michael Kirk, Gordonstoun School MBGRG, FTM vol 1 TB/BA Morayshire Parish Ref. -

SCAAT CRAIG Site of Special Scientific Interest SITE

SCAAT CRAIG Site of Special Scientific Interest SITE MANAGEMENT STATEMENT Site code: 1409 Address: 32 Reidhaven Street, Elgin, Moray IV30 1QH Tel: 01343 541551 email: [email protected] Purpose This is a public statement prepared by SNH for owners and occupiers of the SSSI. It outlines the reasons it is designated as an SSSI and provides guidance on how its special natural features should be conserved or enhanced. This statement does not affect or form part of the statutory notification and does not remove the need to apply for consent for operations requiring consent. We welcome your views on this statement. Description of the site Scaat Craig SSSI encompasses a 700m stretch of the Longmorn Burn. Exposures of loosely consolidated sediments of sandstone and conglomerate along the stream banks have yielded a rich and unusual fossil fauna of well preserved bone fragments, teeth and fish scales. The sediments were formed under the semi-arid conditions about 380 million years ago during the Devonian geological period when this site was probably part of lake and river systems inhabited by fauna typical of that time. Discovered in about 1826, Scaat Craig was one of the first fossil-fish sites to be found in the Moray Firth area. Since several fish species were discovered first at Scaat Craig, it is known as the ‘type locality’ for those species, three of which are known only from this site. Recent work on some of the bones indicates that these are more akin to an amphibian than a fish and therefore the site is very valuable to understanding amphibian and therefore land animal evolution. -

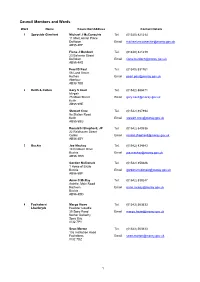

Council Members and Wards

Council Members and Wards Ward Name Councillor/Address Contact Details 1 Speyside Glenlivet Michael J McConachie Tel. (01340) 821214 11 MacLennan Place Dufftown Email [email protected] AB55 4EF Fiona J Murdoch Tel. (01340) 821219 23 Balvenie Street Dufftown Email [email protected] AB55 4AS Pearl B Paul Tel. (01340) 831761 56 Land Street Rothes Email [email protected] Aberlour AB38 7BB 2 Keith & Cullen Gary S Coull Tel. (01542) 888471 Mizpah 75 Moss Street Email [email protected] Keith AB55 5HE Stewart Cree Tel. (01542) 887894 9a Station Road Keith Email [email protected] AB55 5BU Ronald H Shepherd, JP Tel. (01542) 840536 22 Reidhaven Street Cullen Email [email protected] AB56 4SY 3 Buckie Joe Mackay Tel. (01542) 834643 18 Redburn Drive Buckie Email [email protected] AB56 1EW Gordon McDonald Tel. (01542) 850486 1 Howe of Enzie Buckie Email [email protected] AB56 5BF Anne C McK ay Tel. (01542) 839247 Ardelle, Main Road Rathven Email [email protected] Buckie AB56 4DD 4 Fochabers/ Margo Howe Tel. (01343) 563633 Lhanbryde Heelster Gowdie 30 Spey Road Email [email protected] Nether Dallachy Spey Bay IV32 7PY Sean Morton Tel. (01343) 563633 13a Institution Road Fochabers Email [email protected] IV32 7DZ 1 Ward Name Councillor/Address Contact Details Douglas G Ross Tel. (01343) 556677 2 Upper Spynie Steading Pitgaveny Email [email protected] Elgin IV30 5PG 5 Heldon & Laich Eric M McGillivray, JP Parkvale Tel. -

NEWSLETTER Edition 5 November 2010

www.morayandnairnfhs.co.uk Moray & Nairn Family History Society NEWSLETTER Edition 5 November 2010 elcome to the fifth edition of the Moray Jenny Rose-Miller of the Cawdor Heritage & Nairn FHS Newsletter. We are now Society which gave us a „Tour of Historic W approaching the end of our second Nairnshire‟. year, and membership is down slightly on last year. The AGM will be in January (see notice A wide selection of photographs was shown, below). which took the audience to many places in the county, both the well-known ones and also many Please submit articles of local or national interest, of the lesser-known ones, and gave a fascinating as we want to make the newsletter as interesting as picture of the changing ways of life over the years. we can, and the faithful few are running out of The country people no longer carry the „bogle‟ ideas! round the cottage before they go to bed, to ward off evil spirits. Or maybe they do, and just don‟t Ardclach MIs are now published and selling well. admit to it! Auldearn MIs are being tackled next, so watch this space. From Ardclach to Cawdor, from Auldearn to _______________________________________ Nairn, from cottages to castles, and from farming to fishing, the talk had something to interest everyone. Some of the photographs of the town of Nairn in particular brought back fond memories to Annual General Meeting 2011 some of the older members of the audience. The Annual General Meeting will take place on The meeting closed with tea and biscuits, and a Saturday 29 January 2011, 2 pm, at Rivendell, general discussion, especially regarding the Miltonduff, Elgin, IV30 8TJ. -

Elgin, IV30 8RJ Price £98,000 Null Null Null

, Elgin, IV30 8RJ Price £98,000 null null null Elgin, IV30 8RJ Price £98,000 • Excellent Building Plot • Services now being installed • 1,610 sq m (2,000 = 0.5 acres • Beautiful rural outlook and views • Only a few miles from Elgin Stunning new development in the making, comprising 3 fabulous building plots and the existing Easter Whitewreath Farmhouse, all of which will become available for sale in stages. Plot 1 Excellent Building plot extending to 1,610 sq m enjoying a beautiful rural location and elevated situation with outstanding panoramic views facing North ward towards Lossiemouth. Services The building plots are being sold with services which are currently being installed by the owner of Easter Whitewreath Farmhouse. These include electricity, water and a fire hydrant so no large storage tanks needed, a communal septic treatment plant and soakaways The Developer's Obligations of £9,700 have also been paid to the Moray Council for the sites. All interested parties shall require to make their own enquiries and satisfy themselves as to availability and connection of services. Date of Notice The date of notice granted by the council on the Planning Permission is 11th November, 2018. Planning Permission in Principle (Moray Council Planning Reference 18/00851/PPP) has been granted for the Demolition of old steading and erection of No 3 new dwellings. Detailed plans will require to be submitted for approval. Directions Driving from Elgin towards Rothes on the A941 drive through Longmorn and into Fogwatt. Turn left signposted Lhanbryde and Millbuies. Continue past all houses and trees until open fields both sides and Easter Whitewreath is the next set of buildings on the left. -

The Counties of Nairnshire, Moray and Banffshire in the Bronze Age, Part

The counties of Nairnshire, Moray and Banffshire Bronze inth e Age, Par* tII by lain C Walker INTRODUCTION dealinn I g wit bronzee hth s from these three countie traditionae sth l term Earlyf so , Middle, Latd an e Bronz have eAg e been used, though adapte prehistore th aree o dt th outlines aa f yo d thin i s paper span. A Brieflyperioe EB sth e dth , betwee introductioe nth d en e bronzf no th d ean of trade connections betwee aree Ireland nth aan Scandinaviad dan LBe th ; Amarkes i e th y db reappearance of contacts via the Great Glen with Ireland; and the MBA is the intervening period. Metallurgical analyses for Scottish Bronze Age material are in progress and their results, when integrated wit Europeae hth n evidence, necessitaty 1ma emajoa r reappraisa origine th f o ls r metallurgyoou f . However, pendin availabilite gth f thiyo s evidence, this study doe t consno - sider the ore groups found by recent analyses.2 BACKGROUND Hawkes,3 elaborating on the work of Coghlan and Case,4 has suggested that 'Classic' bell beaker folk from the Middle Rhine, arriving in S Ireland and mixing there with the settlers who had introduced the megalithic wedge-shaped tombs from France, were those who initially introduce a copper-usind g economy. Bronze came wit e arrivahth Irelann i l f battle-axo d e people fro Elbe mth e regio woulo nwh d have know rice th h f depositcoppen o ti e d th an rn si Upper Elbe and Saale valleys.