International Scholarly Collaboration: Lessons from the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions Poster Sessions Continuing

Sessions and Events Day Thursday, January 21 (Sessions 1001 - 1025, 1467) Friday, January 22 (Sessions 1026 - 1049) Monday, January 25 (Sessions 1050 - 1061, 1063 - 1141) Wednesday, January 27 (Sessions 1062, 1171, 1255 - 1339) Tuesday, January 26 (Sessions 1142 - 1170, 1172 - 1254) Thursday, January 28 (Sessions 1340 - 1419) Friday, January 29 (Sessions 1420 - 1466) Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions More than 50 sessions and workshops will focus on the spotlight theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting: Transportation for a Smart, Sustainable, and Equitable Future . In addition, more than 170 sessions and workshops will look at one or more of the following hot topics identified by the TRB Executive Committee: Transformational Technologies: New technologies that have the potential to transform transportation as we know it. Resilience and Sustainability: How transportation agencies operate and manage systems that are economically stable, equitable to all users, and operated safely and securely during daily and disruptive events. Transportation and Public Health: Effects that transportation can have on public health by reducing transportation related casualties, providing easy access to healthcare services, mitigating environmental impacts, and reducing the transmission of communicable diseases. To find sessions on these topics, look for the Spotlight icon and the Hot Topic icon i n the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section beginning on page 37. Poster Sessions Convention Center, Lower Level, Hall A (new location this year) Poster Sessions provide an opportunity to interact with authors in a more personal setting than the conventional lecture. The papers presented in these sessions meet the same review criteria as lectern session presentations. For a complete list of poster sessions, see the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section, beginning on page 37. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta The Refugee Woman: Partition of Bengal, Women, and the Everyday of the Nation by Paulomi Chakraborty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Paulomi Chakraborty Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

In East Pakistan (1947-71)

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (Hum.), Vol. 63(1), 2018, pp. 59-89 THE INVISIBLE REFUGEES: MUSLIM ‘RETURNEES’ IN EAST PAKISTAN (1947-71) Anindita Ghoshal* Abstract Partition of India displaced huge population in newly created two states who sought refuge in the state where their co - religionists were in a majority. Although much has been written about the Hindu refugees to India, very less is known about the Muslim refugees to Pakistan. This article is about the Muslim ‘returnees’ and their struggle to settle in East Pakistan, the hazards and discriminations they faced and policy of the new state of Pakistan in accommodating them. It shows how the dream of homecoming turned into disillusionment for them. By incorporating diverse source materials, this article investigates how, despite belonging to the same religion, the returnee refugees had confronted issues of differences on the basis of language, culture and region in a country, which was established on the basis of one Islamic identity. It discusses the process in which from a space that displaced huge Hindu population soon emerged as a ‘gradual refugee absorbent space’. It studies new policies for the rehabilitation of the refugees, regulations and laws that were passed, the emergence of the concept of enemy property and the grabbing spree of property left behind by Hindu migrants. Lastly, it discusses the politics over the so- called Muhajirs and their final fate, which has not been settled even after seventy years of Partition. This article intends to argue that the identity of the refugees was thus ‘multi-layered’ even in case of the Muslim returnees, and interrogates the general perception of refugees as a ‘monolithic community’ in South Asia. -

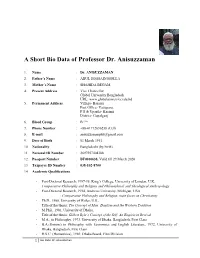

1. Prof. Dr. ANISUZZAMAN

A Short Bio Data of Professor Dr. Anisuzzaman 1. Name : Dr. ANISUZZAMAN 2. Father’s Name : ABUL HOSSAIN MOLLA 3. Mother’s Name : SHAHIDA BEGAM 4. Present Address : Vice Chancellor Global University Bangladesh URL: www.globaluniversity.edu.bd 5. Permanent Address : Village- Barasur Post Office- Vatiapara, P S & Upazila- Kasiani District- Gopalganj 6. Blood Group : B+(ve) 7. Phone Number : +88-01712036238 (Cell) 8. E-mail : [email protected] 9. Date of Birth : 01 March 1951 10. Nationality : Bangladeshi (by birth) 11. National ID Number : 2697557404388 12. Passport Number : BF0010638, Valid till 29 March 2020 13. Taxpayer ID Number : 038-102-8700 14. Academic Qualifications : - Post-Doctoral Research, 1997-98, King’s College, University of London, U.K. Comparative Philosophy and Religion and Philosophical and Theological Anthropology - Post-Doctoral Research, 1994, Andrews University, Michigan, USA : Comparative Philosophy and Religion, main focus on Christianity - Ph.D., 1988, University of Wales, U.K., Title of the thesis: The Concept of Man: Dualism and the Western Tradition - M.Phil., 1981, University of Dhaka, Title of the thesis: Gilbert Ryle’s Concept of the Self: An Empiricist Revival - M.A., in Philosophy, 1973, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh, First Class - B.A.(Honors) in Philosophy with Economics and English Literature, 1972, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh, First Class - H.S.C. (Humanities), 1969, Dhaka Board, First Division 1 Bio Data: Dr. Anisuzzaman - S.S.C., (Humanities), 1967, Dhaka Board, First Division 15. Fields -

Dear Aspirant with Regard

DEAR ASPIRANT HERE WE ARE PRESENTING YOU A GENRAL AWERNESS MEGA CAPSULE FOR IBPS PO, SBI ASSOT PO , IBPS ASST AND OTHER FORTHCOMING EXAMS WE HAVE UNDERTAKEN ALL THE POSSIBLE CARE TO MAKE IT ERROR FREE SPECIAL THANKS TO THOSE WHO HAS PUT THEIR TIME TO MAKE THIS HAPPEN A IN ON LIMITED RESOURCE 1. NILOFAR 2. SWETA KHARE 3. ANKITA 4. PALLAVI BONIA 5. AMAR DAS 6. SARATH ANNAMETI 7. MAYANK BANSAL WITH REGARD PANKAJ KUMAR ( Glory At Anycost ) WE WISH YOU A BEST OF LUCK CONTENTS 1 CURRENT RATES 1 2 IMPORTANT DAYS 3 CUPS & TROPHIES 4 4 LIST OF WORLD COUNTRIES & THEIR CAPITAL 5 5 IMPORTANT CURRENCIES 9 6 ABBREVIATIONS IN NEWS 7 LISTS OF NEW UNION COUNCIL OF MINISTERS & PORTFOLIOS 13 8 NEW APPOINTMENTS 13 9 BANK PUNCHLINES 15 10 IMPORTANT POINTS OF UNION BUDGET 2012-14 16 11 BANKING TERMS 19 12 AWARDS 35 13 IMPORTANT BANKING ABBREVIATIONS 42 14 IMPORTANT BANKING TERMINOLOGY 50 15 HIGHLIGHTS OF UNION BUDGET 2014 55 16 FDI LLIMITS 56 17 INDIAS GDP FORCASTS 57 18 INDIAN RANKING IN DIFFERENT INDEXS 57 19 ABOUT : NABARD 58 20 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 58 21 OSCAR AWARD 2014 59 22 STATES, CAPITAL, GOVERNERS & CHIEF MINISTERS 62 23 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 62 23 LIST OF IMPORTANT ORGANIZATIONS INDIA & THERE HEAD 65 24 LIST OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND HEADS 66 25 FACTS ABOUT CENSUS 2011 66 26 DEFENCE & TECHNOLOGY 67 27 BOOKS & AUTHOURS 69 28 LEADER”S VISITED INIDIA 70 29 OBITUARY 71 30 ORGANISATION AND THERE HEADQUARTERS 72 31 REVOLUTIONS IN AGRICULTURE IN INDIA 72 32 IMPORTANT DAMS IN INDIA 73 33 CLASSICAL DANCES IN INDIA 73 34 NUCLEAR POWER -

Kashmiriyat, Featured Culture of Bhakti-Sufi-Rishi Singhs, and an Junoon and the Music Concert India/Pakistan Artists

KASHMIRIYAT couv Janv 09:Layout 1 8/04/09 11:58 Page 1 Madanjeet Singh The two unique and memorable events that South Asia Foundation (SAF) organized in Srinagar to commemorate the Bhakti-Sufi-Rishi culture of Kashmiriyat, featured a jointly held India/Pakistan music concert Junoon and the Singhs, and an unprecedented exhibition of paintings by South Asian women artists. Madanjeet Singh narrates an account of these events, providing insights into age-old links between the music and art of South Asia and the pluralist culture and legacy of Kashmiriyat. KASHMIRIYAT Madanjeet Singh was born on 16 April 1924 in Lahore, present-day Pakistan. A well-known painter and a distinguished photographer, he is an internationally known author of several books on art and other subjects, closely interwoven with UNESCO’s programmes, principles and ideals. During Mahatma Gandhi’s ‘Quit India’ movement in 1942 against colonial rule, Madanjeet Singh was imprisoned. He later migrated to newly partitioned India in 1947 and worked in a refugee camp. He joined the Indian Foreign Service in 1953 and served as Ambassador of India in Asia, South America, Africa and Europe before joining UNESCO in1982, based in Paris. South Asia Foundation At the inaugural ceremony of the Institute of Kashmir Studies on 26 May 2008, Madanjeet Singh presented President Pratibha In 1995, in recognition of his lifelong devotion to the cause of Patil with a copy of his book, This My People, to which Prime communal harmony and peace, the UNESCO Executive Board Minister Jawaharlal Nehru handwrote a preface, shortly after created the biennial ‘UNESCO-Madanjeet Singh Prize for the India’s Partition in 1947. -

Negotiating Modernity and Identity in Bangladesh

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 9-2020 Thoughts of Becoming: Negotiating Modernity and Identity in Bangladesh Humayun Kabir The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4041 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THOUGHTS OF BECOMING: NEGOTIATING MODERNITY AND IDENTITY IN BANGLADESH by HUMAYUN KABIR A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 HUMAYUN KABIR All Rights Reserved ii Thoughts Of Becoming: Negotiating Modernity And Identity In Bangladesh By Humayun Kabir This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________ ______________________________ Date Uday Mehta Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ ______________________________ Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Uday Mehta Susan Buck-Morss Manu Bhagavan THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Thoughts Of Becoming: Negotiating Modernity And Identity In Bangladesh By Humayun Kabir Advisor: Uday Mehta This dissertation constructs a history and conducts an analysis of Bangladeshi political thought with the aim to better understand the thought-world and political subjectivities in Bangladesh. The dissertation argues that political thought in Bangladesh has been profoundly structured by colonial and other encounters with modernity and by concerns about constructing a national identity. -

Book List of PIB Library

Book List of PIB Library Sl . No. Autho r/Editor Title Year of Publication 1. Aaker, David A. Advertising management 1977 2. Aaker, David A. Advertising management: practical perspectives 1975 3. Aaron, Daniel (ed.) Paul Eimer More’s shelburne essays on American literature 1963 4. Abbo t, Waldo. Handbook of broadcasting: the fundamentals of radio and 1963 television 5. Abbouhi, W.F. Political systems of the middle east in the 20 th century 1970 6. Abcarian, Cilbert Contemporary political systems: an introduction to government 1970 7. Abdel -Agig, Mahmod Nuclear proliferation and hotional security 1978 8. Abdullah, Abu State market and development: essays in honour of Rehman 1996 Sobhan 9. Abdullah, Farooq. My dismissal 1985 10. Abdullah, Muhammad Muslim sampadita bangla samayikpatra dharma o sam aj chinta 1995 (In Bangla) 11. Abecassis, David Identity, Islam and human development in rural Bangladesh 1990 12. Abel, Ellie. (ed.) What’s news: the media in American society 1981 13. Abir, Syed. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib: alaukik mohima (In Bangla) 2006 14. Abra ham, Henry J. The judicial process: an introductory analysis of the courts of the 1978 United States, England and France 15. Abrams, M. H. Natural supernaturalism: tradition and revolution in romantic 1973 literature 16. Abramson, Norman Information theory and coding 1963 17. Abundo, Romoo B. Print and broadcast media in the South pacific 1985 18. Acharjee, Jayonto Anusandhani pratibedan dristir antarate (In Bangla) 2003 19. Acharya, P. Shabdasandhan Shabdahidhan (In Bangla) - 20. Acharya, Rabi Narayan Television in India: a sociological study of policies and 1987 perspectives 21. Acharya, Ram Civil aviation and tourism administration in India 1978 22. -

Quick Reference Guide for SBI PO Online Exam 2014 Powered By

Quick Reference Guide for SBI PO Online Exam 2014 Powered by www.Gr8AmbitionZ.com your A to Z competitive exam guide CURRENT AFFAIRS QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE FOR SBI PO ONLINE EXAM 2014 www.Gr8AmbitionZ.com Important Points you should know about State Bank of India State Bank of India o SBI is the largest banking and financial services company in India by assets. The bank traces its ancestry to British India, through the Imperial Bank of India, to the founding in 1806 of the Bank of Calcutta, making it the oldest commercial bank in the Indian Subcontinent. Bank of Madras merged into the other two presidency banks Bank of Calcutta and Bank of Bombay to form the Imperial Bank of India, which in turn became the State Bank of India. Government of India nationalized the Imperial Bank of India in 1956, with Reserve Bank of India taking a 60% stake, and renamed it the State Bank of India. In 2008, the government took over the stake held by the Reserve Bank of India. o CMD : Smt. Arundathi Bhattacharya (first woman to be appointed Chairperson of the bank) o Headquarters : Mumbai o Associate Banks : SBI has five associate banks; all use the State Bank of India logo, which is a blue circle, and all use the "State Bank of" name, followed by the regional headquarters' name: . State Bank of Bikaner & Jaipur . State Bank of Hyderabad . State Bank of Mysore . State Bank of Patiala . State Bank of Travancore . Note : Earlier SBI had seven associate banks. State Bank of Saurashtra and State Bank of Indore merged with SBI on 13 August 2008 and 19 June 2009 respectively. -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt. -

Padma Awards - One of the Highest Civilian Awards of the Country, Are Conferred in Three Categories, Namely, Padma Vibhushan, Padma Bhushan and Padma Shri

Padma Awards - one of the highest civilian Awards of the country, are conferred in three categories, namely, Padma Vibhushan, Padma Bhushan and Padma Shri. The Awards are given in various disciplines/ fields of activities, viz.- art, social work, public affairs, science and engineering, trade and industry, medicine, literature and education, sports, civil service, etc. ‘Padma Vibhushan’ is awarded for exceptional and distinguished service; ‘Padma Bhushan’ for distinguished service of high order and ‘Padma Shri’ for distinguished service in any field. The awards are announced on the occasion of Republic Day every year. 2. These awards are conferred by the President of India at ceremonial functions which are held at Rashtrapati Bhawan usually around March/ April every year. This year the President of India has approved conferment of 127 Padma Awards including one duo case (counted as one) as per the list below. The list comprises of 2 Padma Vibhushan, 24 Padma Bhushan and 101 Padma Shri Awardees. 27 of the Awardees are women and the list also includes 10 persons from the category of foreigners, NRIs, PIOs and Posthumous Awardees. Padma Vibhushan Sl No. Name Discipline State/ Domicile 1. Dr. Raghunath A. Mashelkar Science and Engineering Maharashtra 2. Shri B.K.S. Iyengar Others-Yoga Maharashtra Padma Bhushan Sl No. Name Discipline State/ Domicile 1. Prof. Gulam Mohammed Sheikh Art - Painting Gujarat 2. Begum Parveen Sultana Art - Classical Singing Maharashtra 3. Shri T.H. Vinayakram Art - Ghatam Artist Tamil Nadu 4. Shri Kamala Haasan Art-Cinema Tamil Nadu 5. Justice Dalveer Bhandari Public Affairs Delhi 6. Prof. Padmanabhan Balaram Science and Engineering Karnataka 7. -

Paulomi Chakraborty

University of Alberta The Refugee Woman: Partition of Bengal, Women, and the Everyday of the Nation by Paulomi Chakraborty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Paulomi Chakraborty Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Stephen Slemon, English and Film Studies Heather Zwicker, English and Film Studies Onookome Okome, English and Film Studies Sourayan Mookerjea, Sociology Rajeswari Sunder Rajan, English, New York University I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of Rani Chattopadhyay and Birendra Chattopadhyay, my grandparents Abstract In this dissertation I analyze the figure of the East-Bengali refugee woman in Indian literature on the Partition of Bengal of 1947. I read the figure as one who makes visible, and thus opens up for critique, the conditions that constitute the category ‘women’ in the discursive terrain of post-Partition/post-Independence India.