Translation & Music in Brazil1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric LuMing Mao Morris Young Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Mao, LuMing and Young, Morris, "Representations: Doing Asian American Rhetoric" (2008). All USU Press Publications. 164. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/164 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS REPRESENTATIONS Doing Asian American Rhetoric edited by LUMING MAO AND MORRIS YOUNG UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2008 Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Cover design by Barbara Yale-Read Cover art, “All American Girl I” by Susan Sponsler. Used by permission. ISBN: 978-0-87421-724-7 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-87421-725-4 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Representations : doing Asian American rhetoric / edited by LuMing Mao and Morris Young. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-87421-724-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-87421-725-4 (e-book) 1. English language--Rhetoric--Study and teaching--Foreign speakers. 2. Asian Americans--Education--Language arts. 3. Asian Americans--Cultural assimilation. -

Billboard-1987-11-21.Pdf

ICD 08120 HO V=.r. (:)r;D LOE06 <0 4<-12, t' 1d V AiNE3'c:0 AlNClh 71. MW S47L9 TOO, £L6LII.000 7HS68 >< .. , . , 906 lIOIa-C : , ©ORMAN= $ SPfCl/I f011I0M Follows page 40 R VOLUME 99 NO. 47 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT November 21, 1987/$3.95 (U.S.), $5 (CAN.) CBS /Fox Seeks Copy Depth Many At Coin Meet See 45s As Strong Survivor with `Predator' two -Pack CD Jukeboxes Are Getting Big Play "Predator" two-pack is Jan. 21; indi- and one leading manufacturer Operators Assn. Expo '87, held here BY AL STEWART vidual copies will be available at re- BY MOIRA McCORMICK makes nothing else. Also on the rise Nov. 5-7 at the Hyatt Regency Chi- NEW YORK CBS /Fox Home Vid- tail beginning Feb. 1. CHICAGO While the majority of are video jukeboxes, some using la- cago. More than 7,000 people at- eo will test a novel packaging and According to a major -distributor jukebox manufacturers are confi- ser technology, that manufacturers tended the confab, which featured pricing plan in January, aimed at re- source, the two -pack is likely to be dent that the vinyl 45 will remain a say are steadily gaining in populari- 185 exhibits of amusement, music, lieving what it calls a "critical offered to dealers for a wholesale viable configuration for their indus- ty. and vending equipment. depth -of-copy problem" in the rent- price of $98.99. Single copies, which try, most are beginning to experi- Those were the conclusions Approximately 110,000 of the al market. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

The Teacher and Teacher-Librarian INSTITUTION British

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 411 789 IR 056 483 TITLE Literature Connections: The Teacher and Teacher-Librarian Partnership. INSTITUTION British Columbia Dept. of Education, Victoria. Learning Resources Branch. ISBN ISBN-0-7726-1300-1 PUB DATE 1991-00-00 NOTE 180p. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Development; *English Curriculum; Foreign Countries; *Information Literacy; Language Arts; Learning Resources Centers; *Librarian Teacher Cooperation; Library Planning; Library Services; Program Development; *School Libraries; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Resource Based Learning ABSTRACT This book is designed to help teachers, teacher-librarians, administrators, and district staff create a literature program that integrates literature within the context of resource-based learning. The book is organized into three sections. Part 1: "Critical Components of Learning through Literature" discusses in detail how each of the components vital to learning through literature may be implemented in a library resource center program by teachers and teacher-librarians as they plan and teach together. These critical components identified in Part 1 are intrinsically tied to three essential focuses of a literature program: building a climate for literacy; applying current knowledge about the nature of student learning processes; and the refinement and maintenance of sound instructional practice. Part 2: "Critical Components Po.plied" provides teachers and teacher-librarians with nine cooperatively-planned -

Il-Y-A-Paroless

Vanessa Paradis Il y a là la peinture Vanessa Paradis Des oiseaux, l'envergure Qui luttent contre le vent Vanessa Paradis, née le 22 décembre 1972 à Saint-Maur- Il y a là les bordures des-Fossés (Val-de-Marne), est Les distances, ton allure une chanteuse, actrice et mannequin Quand tu marches juste devant française. Il y a là les fissures Elle devient célèbre dès l'âge de Fermées les serrures quatorze ans avec son premier Comme envolés les cerfs-volants disque Joe le taxi et mène, depuis, une carrière dans la musique, le Il y a là la littérature cinéma et la mode. Le manque d'élan Elle travaillera ensuite à partir de 1990 avec Alain Souchon L'inertie, le mouvement et Renaud, puis avec Serge Gainsbourg (Tandem, dis-lui toi ’ Refrain que je t aime) ou encore avec Lenny Kravitz en 1992 où elle chante en anglais avec des tubes comme Be my baby. Parfois on regarde les choses Le succès reviendra en 2007 avec son album Divine Idylle Telles qu'elles sont écrit par Mathieu Chédid, dit M. Celui-ci la fera également En se demandant pourquoi interpréter la chanson La Seine, la BO du film « Un monstre Parfois, on les regarde » Telles qu'elles pourraient être à Paris en 2011. En se disant pourquoi pas La chanson Il y a lalala Cette chanson est le 28e single de Vanessa Paradis. Il est Si l'on prenait le temps écrit et composé par Gaëtan Roussel, le leader du Si l'on prenait le temps groupe Louise Attaque. -

A Success Story

ANNUAL REPORT 2009 M6 Group 2009 Annual Report / 1 CONTENTS 2 7 A SUCCESS STORY 16 47 THE GROUP’S ACTIVITIES 48 53 WE SPECIALISE IN DISCOVERING 74 83 STANDING BY OUR VALUES NEW TALENT IS THE BEST WAY TO CREATE 8 9 Message from Nicolas de Tavernost 18 21 Our Expertise: TV Relevant to People’s Lives NEW ONES 54 73 DUTY BOUND BY 10 11 Message from Thomas Valentin 22 25 Bold and Clear: News the M6 Way OUR BUSINESS ACTIVITIES 76 79 Corporate Governance 12 15 A Balanced and Effective 26 29 Sport: Where Enthusiasm Sets Off the Emotions 64 65 Programmes Making Sense of the News 80 81 Shareholders’ Notebook - Development Model and Accessible to All Viewers The 2009 Financial Year 30 31 Drama & Series: Put Your Feet Up and Leave the Rest to Us 66 67 Acting for the Planet 82 83 Key Indicators and Our Future Environment 32 35 Cinema: Producing, Buying, Distributing and Broadcasting Films for a Wide Audience 68 69 Working Towards a More Cohesive Company 36 37 Events and Entertainment: Art, Music and Shows - 70 71 Creating and Sustaining the Conditions for We Make Them More Lively Financial, Profi table and Responsible Growth 38 39 Laughter and Relaxation 72 73 Creating a Stimulating and Respectful Work Environment 40 41 Our Know-How is to Dream Up New Brands and Other Concepts 42 45 Internet: Look, Look Again, Research... Another Television 46 47 Ventadis: Shopping in Front of a Screen A Success Story M6 Group 200920 Annual Report 2 / 3 03 / 1987 06 / 1987 09 / 1987 A 1997 SUCCESS 1987-1991 1987 LAUNCH OF M6 2009 STORY THE YOUNG CHANNEL ON THE RISE M6 was established in March 1987. -

Japanese Women, Hong Kong Films, and Transcultural Fandom

SOME OF US ARE LOOKING AT THE STARS: JAPANESE WOMEN, HONG KONG FILMS, AND TRANSCULTURAL FANDOM Lori Hitchcock Morimoto Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication and Culture Indiana University April 2011 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _______________________________________ Prof. Barbara Klinger, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Gregory Waller, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Michael Curtin, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Michiko Suzuki, Ph.D. Date of Oral Examination: April 6, 2011 ii © 2011 Lori Hitchcock Morimoto ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii For Michael, who has had a long “year, two at the most.” iv Acknowledgements Writing is a solitary pursuit, but I have found that it takes a village to make a dissertation. I am indebted to my advisor, Barbara Klinger, for her insightful critique, infinite patience, and unflagging enthusiasm for this project. Gratitude goes to Michael Curtin, who saw promise in my early work and has continued to mentor me through several iterations of his own academic career. Gregory Waller’s interest in my research has been gratifying and encouraging, and I am most appreciative of Michiko Suzuki’s interest, guidance, and insights. Richard Bauman and Sumie Jones were enthusiastic readers of early work leading to this dissertation, and I am grateful for their comments and critique along the way. I would also like to thank Joan Hawkins for her enduring support during her tenure as Director of Graduate Studies in CMCL and beyond, as well as for the insights of her dissertation support group. -

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

Distinction in China— the Rise of Taste in Cultural Consumption

The London School of Economics and Political Science Distinction in China— the rise of taste in cultural consumption Gordon C. Li A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, May 2020 Distinction in China—the rise of taste in cultural consumption 2 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgment is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 90,363 words. Distinction in China—the rise of taste in cultural consumption 3 Abstract This research studies how cultural consumption draws cultural distinctions in the most developed megacities in China. This research examines the pattern of music consumption to examine distinction—which types of music are used, how they are used, who are using them, and what are the sources of those tastes. Although some theories, such as the cultural omnivore account, contend that the rise of contemporary pop culture implies a more open-minded pursuit of taste, this research argues that popular culture draws distinction in new ways. -

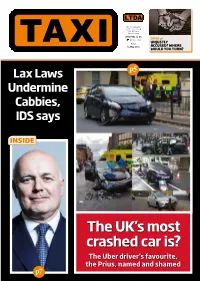

The UK's Most Crashed Car

LTDA The newspaper of the Licensed Taxi Drivers’ Association www.ltda.co.uk SAVED: p2 @TheLTDA #443 UNJUSTLY 14 May 2019 ACCUSED? WHERE WOULD YOU TURN? p Lax Laws 5 Undermine Cabbies, IDS says The UK’s most crashed car is? The Uber driver’s favourite, the Prius, named and shamed p7 2 TAXI |||| 14 May 2019 www.ltda.co.uk |||| @TheLTDA Lax Laws Undermine Cabbies, IDS says POLITICS Uber’s “business model allows it to operate on a completely different playing London’s black cab drivers face unfair field. It arrives in our towns offering competition and the Government must be unrealistically low prices that local taxi more ambitious in its reforms, the former and private hire drivers simply can’t pensions secretary has said. match.” Iain Duncan Smith, the MP for He adds that Uber drivers are effectively Chingford and Woodford Green, has being allowed to ply for hire through the expressed his disappointment that app, while the current licensing system “sensible” recommendations made by the puts passengers in danger. All-Party Parliamentary Group on Taxis Mr Duncan Smith supports calls for were watered down. local Government to be given the power IDS praised the London taxi trade as to cap private hire numbers. possibly the most admired in the world He adds: “New legislation also needs but says it has been badly let down by the to finally set out in law who is allowed failure to update legislation to maintain a to ‘ply for hire’, and who is not. It must level playing field. define where drivers are allowed to work In a swipe at new technology “Taxi and private hire laws need a complete rewrite” to improve accountability and safety.” companies, such as Uber, the MP said that “I believe in strong competitive markets, some “new players” have “refused to play “Some of the laws governing taxis date Plans for national minimum licensing but competition must be fair.