Landscape and the Montgomery Canal Corridor (1.1MB PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Coach House, Llanymynech, SY22 6JZ £244,950

www.townandcountryoswestry.com 4 Willow Street, Oswestry, Shropshire, SY11 1AA TEL: 01691 679631 [email protected] Old Coach House, Llanymynech, SY22 6JZ £244,950 NO CHAIN!! WE ARE PLEASED TO OFFER THIS SUPERB THREE BEDROOM DETACHED COTTAGE WITH OUTSTANDING VIEWS AND 1/3 OF AN ACRE OF SLOPING GARDEN TO THE REAR. Close to the villages of Llanymynech and Pant. There are primary schools and other facilities which include shops, public houses and churches with road access into Oswestry, Shrewsbury and Welshpool. The property which has spacious lawned terraced gardens is approached by a driveway which provides off road parking for a number of vehicles. Accommodation briefly comprises - Lounge, Dining Room, Kitchen/Breakfast Room, Conservatory, Down Stairs Shower Room, Three Bedrooms and a Bathroom. Outside there is a garage with inspection pit. VIEWING IS HIGHLY RECOMMENDED TO APPRECIATE THIS LOVELY PROPERTY AND ITS LOCATION. Old Coach House, Llanymynech, SY22 6JZ Directions From Oswestry take the Welshpool Road and proceed through the village of Pant. Before entering Llanymynech take a right hand turn signposted Penyfoel. Follow the road along where the property will be seen on the left after approximately 500 metres. Accommodation Comprises Hall With a glazed door to the front, window to the front, radiator and stairs leading to the first floor. Dining Room 2.84 x 3.53 (9'4" x 11'7") With built in cupboard, wall lights, radiator and patio doors leading to the conservatory. Kitchen/Breakfast Room 3.55 x 3.6 (11'8" x 11'10") With a window to the front, glazed door to the side, base and wall units, plumbing for a washing machine, Mistral oil fired boiler, part tiled walls, vinyl floor, radiator, stainless steel single drainer sink unit with mixer tap and porch off to the side. -

Cyngor Cymuned Carreghofa Community Council

Cyngor Cymuned Carreghofa Community Council Minutes of the Meeting held on Tuesday 27th October 2015 at Llanymynech Village Hall Present: Cllr D Thornycroft (Chair) Cllr C Backshall, Cllr D Borthwick Cllr M Connell Cllr R McCluskey Cllr B Richardson County Councillor Arwel Jones In attendance: Mr M Donkin – Clerk to the Council 1 Apologies for Absence Cllr F James – students Cllr C Jones – family matters 2. To record Declarations of Interest in items on the agenda: None 3. To confirm the minutes of the meeting held on Tuesday 29th September 2015: The minutes were approved as a correct record and signed by the Chairman. 4. Matters arising from the minutes that are not on the agenda: 4.1. Defibrillator – Community Awareness Evening Cllr Backshall confirmed that publicity has been circulated in the Parish Magazine and ‘The Bridge’. He will be publishing an article in these papers on the provision of the Llanymynech defibrillator and will offer this to the local press. This will cover the Lottery Grant, the agreement .of the landlord of the Dolphin hotel to accommodate the defibrillator and a request for local people to be responsible for monitoring the defibrillator once each week. The article will coincide with the awareness training on 1st December. Cllr Backshall asked that as many councillors as possible should attend the awareness training. 4.2 Register of Members’ Interests. All councillors have now submitted their Register of Interest forms. 4.3. Smoke Free Playgrounds In answer to a question from the Clerk, Cllr Backshall said that he had not received any posters from Public Health, Wales. -

Marches and Mid Wales Freight Strategy – Technical Annex

The Marches & Mid Wales Freight Strategy Technical Annex CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Scope ...................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Approach ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 2 DATA ANALYSIS ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Methodology .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Freight generators & attractors .............................................................................................................................. 3 2.3 Transport geography ............................................................................................................................................ 13 2.4 Road freight .......................................................................................................................................................... 15 2.5 Rail freight ........................................................................................................................................................... -

3. Development Management Policies

Shropshire Council Site Allocations and Management of Development (SAMDev) Plan Pre-Adoption Version (Incorporating Inspector’s Modifications) Full Council 17th December 2015 3. Development Management Policies MD1 : Scale and Distribution of Development Further to the policies of the Core Strategy: 1. Overall, sufficient land will be made available during the remainder of the plan period up to 2026 to enable the delivery of the development planned in the Core Strategy, including the amount of housing and employment land in Policies CS1 and CS2. 2. Specifically, sustainable development will be supported in Shrewsbury, the Market Towns and Key Centres, and the Community Hubs and Community Cluster settlements identified in Schedule MD1.1, having regard to Policies CS2, CS3 and CS4 respectively and to the principles and development guidelines set out in Settlement Policies S1-S18 and Policies MD3 and MD4. 3. Additional Community Hubs and Community Cluster settlements, with associated settlement policies, may be proposed by Parish Councils following formal preparation or review of a Community-led Plan or a Neighbourhood Plan and agreed by resolution by Shropshire Council. These will be formally considered for designation as part of a Local Plan review. Schedule MD1.1: Settlement Policy Framework: County Town and Sub-regional Centre Shrewsbury Market Towns and Key Centres Oswestry Bishop’s Castle Ellesmere Cleobury Mortimer Whitchurch Bridgnorth Market Drayton Shifnal Wem Much Wenlock Minsterley/Pontesbury Broseley Ludlow Highley Craven Arms -

Cyngor Cymuned Carreghofa Community Council

Cyngor Cymuned Carreghofa Community Council Minutes of the Meeting held on Tuesday 27th March 2018 at Llanymynech Village Hall Present: Cllr M Connell (Chairman) Cllr D Cavill Cllr R Dover Cllr F James Cllr R McCluskey Cllr S Morris In attendance: Mr M Donkin – Clerk to the Council 1. Apologies for absence Cllr C Jones County Cllr Arwel Jones 2. To record Declarations of Interest in items on the agenda None 3. To confirm the minutes of the meeting held on Tuesday 27th February 2018 The minutes were approved as a correct record and signed by the Chair 4. Matters arising from the minutes 4.1. Vyrnwy Valley Marketing association The Clerk confirmed that Mr Blacker has been invited to address the Council and he will attend at the next meeting. 4.2. Kidney Wales Walk for Life The Clerk reported that Cllr Jones had brought the above event to the attention of the walking club but that there was no enthusiasm for taking up the project. 5. Finance Report 5.1. Council noted the financial position as set out in the papers for the meeting. 5.2. Payments to members of community and town councils Council considered the determinations set out by the Independent Review Panel for Wales and made the following decisions:- Determination 44 - decline Determination 45 - accept in respect of the Data Protection regulations Determination 46 - accept Determination 47 - decline Determination 48 - accept Determination 49 - accept 1 Determination 50 - accept Determination 51 - accept 5.3. The Clerk read out a letter from Llanymynech Good Companions asking the Council for financial support. -

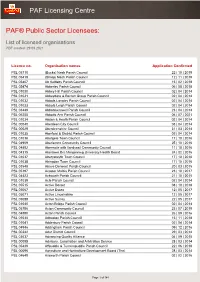

List of Licensed Organisations PDF Created: 29 09 2021

PAF Licensing Centre PAF® Public Sector Licensees: List of licensed organisations PDF created: 29 09 2021 Licence no. Organisation names Application Confirmed PSL 05710 (Bucks) Nash Parish Council 22 | 10 | 2019 PSL 05419 (Shrop) Nash Parish Council 12 | 11 | 2019 PSL 05407 Ab Kettleby Parish Council 15 | 02 | 2018 PSL 05474 Abberley Parish Council 06 | 08 | 2018 PSL 01030 Abbey Hill Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01031 Abbeydore & Bacton Group Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01032 Abbots Langley Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01033 Abbots Leigh Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 03449 Abbotskerswell Parish Council 23 | 04 | 2014 PSL 06255 Abbotts Ann Parish Council 06 | 07 | 2021 PSL 01034 Abdon & Heath Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00040 Aberdeen City Council 03 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00029 Aberdeenshire Council 31 | 03 | 2014 PSL 01035 Aberford & District Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01036 Abergele Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04909 Aberlemno Community Council 25 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04892 Abermule with llandyssil Community Council 11 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04315 Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board 24 | 02 | 2016 PSL 01037 Aberystwyth Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 01038 Abingdon Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 03548 Above Derwent Parish Council 20 | 03 | 2015 PSL 05197 Acaster Malbis Parish Council 23 | 10 | 2017 PSL 04423 Ackworth Parish Council 21 | 10 | 2015 PSL 01039 Acle Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 05515 Active Dorset 08 | 10 | 2018 PSL 05067 Active Essex 12 | 05 | 2017 PSL 05071 Active Lincolnshire 12 | 05 -

247-Balfours.Pdf

Settlement Area Total Allocation Provision Allocated Albrighton 250 200 Bishops Castle 150 40 Bucknell h 100 70 Chirbury h 30 30 Clun h 70 60 Lydbury North h 20 20 Brompton, Marton, Middleton, Pentreheyling, Priest Weston, Stockton adn Rorrington c 20 0 Abcot, eckjay, Clungunford, Hopton Heth, Shelderton and Twitchen c 15 0 Hope, Bentlawnt, Hopesgte, Hemford, Shelve, Gravels, Pentervin, Bromlow, Middleton, Meadowtown and Lordstone c 15 0 Snailbeach, Stiperstones, Pennerley, Tankerville, Black Hole, Crows Nes and The Bog c 15 0 Wentnor and Norbury c 25 0 Worthen, Brockton, Little Worthen, Little Brockton, Binweston, Leigh, rowley, Aston Rogers and Aston Pigott c 30 0 Bridgnorth 1,400 500 Ditton Priors h 26 12 Neenton c 7 7 Acton Round, Aston Eyre, Monkhopton, Morville and Upton Cressett c 15 0 Broseley 200 0 Church Stretton 370 100 Cleobury Mortimeer 350 19 Kinlet, Button Bridge, Button Oak c 30 20 Hopton Wafers and Doddington c 12 0 Oreton, Farlow and Hill Houses c 12 0 Silvington, Bromdon, Louhton and Wheathill c 12 0 Stottersdon, Chorley and Bagginswood c 12 0 Craven Arms 500 350 Aston on Clun, Hopesay, Broome, Horderley, Beambridge Long Meadow End, Rowton, Round Oak c 15 0 Bache Mill, Boulton, Broncroft, Corfton, Middlehope, Peaton, Seifton, Sutton, Westhope c 45 0 Stoke St Milborough, Hopton Cangeford, Cleestanton, Cleedownton c 10 Ellesmere 800 250 Cockshutt h 50 20 Duddleston Heath/Elson h 40 20 Duddleston and Street Dinas c 10 0 Tetchill, Lee and Whitemere c 20 10 Welsh Frankton, Perthy, New Marton and Lower Frankton c 30 15 Welshamton -

Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society

ISSN 0143-5175 Shropshire History and Archaeology Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society (incorporating the Shropshire Parish Register Society) VOLUME LXXXVII edited by D. T. W. Price SHREWSBURY 2012 (ISSUED IN 2014) © Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society. Produced and printed by 4word Ltd., Bristol COUNCIL AND OFFICERS 1 APRIL 2014 President SIR NEIL COSSONS, O.B.E., M.A., F.S.A. Vice-Presidents ERNIE JENKS MADGE MORAN, F.S.A. M. UNA REES, B.A., PH.D. B. S. TRINDER, M.A., PH.D., F.S.A. Elected Members NIGEL BAKER, B.A., PH.D., F.S.A., M.I.F.A. MARY F. MCKENZIE, M.A., M.AR.AD. NEIL CLARKE, B.A. MARTIN SPEIGHT, B.A., PH.D. ROBERT CROMARTY, B.A. ROGER WHITE, B.A., PH.D., M.I.F.A. HUGH HANNAFORD, M.I.F.A. ANDYWIGLEY, B.SC., M.A., PH.D., F.S.A., P.C.H.E. W. F. HODGES Chairman JAMES LawsON, M.A., Westcott Farm, Habberley, Shrewsbury SY5 0SQ Hon. Secretary and Hon. Publications Secretary G. C. BAUGH, M.A., F.S.A., Glebe House, Vicarage Road, Shrewsbury SY3 9EZ Hon. Treasurer FRANCESCA BUMPUS, M.A., PH.D., 9 Alexandra Avenue, Meole Brace, Shrewsbury SY3 9HT Hon. Membership Secretary PENNY WARD, M.A., M.I.F.A., 1 Crewe Street, Shrewsbury SY3 9QF Hon. -

Regulation 19: Pre-Submission Draft of the Shropshire Local Plan 2016 to 2038

Shropshire Council Regulation 19: Pre-Submission Draft of the Shropshire Local Plan 2016 to 2038 December 2020 Regulation 19: Pre-Submission Draft of the Shropshire Local Plan Page 0 1. Contents 2. Introduction ...................................................................................... 6 Shropshire’s Character ................................................................................... 6 National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) ................................................ 8 The Shropshire Local Plan 2016 to 2038 ....................................................... 8 Cross Boundary Issues and the Duty to Cooperate ................................... 10 Infrastructure ................................................................................................. 10 Neighbourhood Plans and Community Led Plans ...................................... 10 3. Strategic Policies ........................................................................... 12 SP1. The Shropshire Test ......................................................................... 12 SP2. Strategic Approach ........................................................................... 13 SP3. Climate Change ................................................................................. 22 SP4. Sustainable Development................................................................. 25 SP5. High-Quality Design .......................................................................... 26 SP6. Health and Wellbeing ....................................................................... -

NOTICE of ELECTION Shropshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parish Listed Below

NOTICE OF ELECTION Shropshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parish listed below Number of Parish Parish Councillors to be elected Llanymynech and Pant Parish Council Eleven 1. Forms of nomination for the above election may be obtained from the Clerk to the Parish Council, or the Returning Officer at the Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Nomination papers must be hand-delivered to the Returning Officer, Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6ND on any day after the date of this notice but no later than 4 pm on Thursday, 8th April 2021. Alternatively, candidates may submit their nomination papers at the following locations on specified dates, between the times shown below: Shrewsbury Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, SY2 6ND 9.00am – 5.00pm Weekdays from Tuesday 16th March to Thursday 1st April. 9.00am – 7.00pm Tuesday 6th April and Wednesday 7th April. 9.00am – 4.00pm Thursday 8th April. Oswestry Council Chamber, Castle View, Oswestry, SY11 1JR 8.45am – 6.00pm Tuesday 16th March; Thursday 25th March and Wednesday 31st March. Wem Edinburgh House, New Street, Wem, SY4 5DB 9.15am – 4.30pm Wednesday 17th March; Monday 22nd March and Thursday 1st April. Ludlow Helena Lane Day Care Centre, 20 Hamlet Road, Ludlow, SY8 2NP 8.45am – 4.00pm Thursday 18th March; Wednesday 24th March and Tuesday 30th March. Bridgnorth Bridgnorth Library, 67 Listley Street, Bridgnorth, WV16 4AW 9.45am – 4.30pm Friday 19th March; Tuesday 23rd March and Monday 29th March. -

A Guide to the Family and Local History Resources Available at Oswestry

A Guide to the Family and Local History Resources available at Oswestry Library 29/09/2015 1 Version 3 Contents Parish Registers & Monumental inscriptions……….……………….…………….. 3 Trade Directories ........................................................................... …………..………….. 22 Electoral Registers ................................................................................................................... 25 Newspapers & Periodicals held in Oswestry Library................................................... 27 BCA Hard Copy Newspapers held in Guild Hall ………………………………. .... 32 Newspapers Alphabetical Index to Marriages & Deaths & Subject Cards…. ...... 33 Parish and Village Magazines & Newsletters ........................................................ 35 Quarter Sessions ................................................................................................... 36 Oswestry Town Council Archive ........................................................................................... 36 Maps and Plans ..................................................................................................... 37 Field Name Maps………………………………………………………….. 37 Ordnance Survey Maps…………………………………………………… 38 Other Maps…………………………………………………………………. 38 Tithe Apportionments…………………………………………………………….. 38 Printed Material ...................................................................................................... 38 Photographs, Postcards and Prints ..................................................................................... -

FOI REQUEST 7078/1 Racist Incidents and Racially Motivated Hate Crimes All Racist Incidents Offence Category Crimed Incident

FOI REQUEST 7078/1 racist incidents and racially motivated hate crimes All racist incidents Offence Category Crimed Incident BCU Beats/Parish 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Grand Total Herefordshire ASTON INGHAM 1 1 BROMYARD & WINSLOW 1 1 2 CLIFFORD 1 1 CRADLEY 1 1 CREDENHILL 1 1 2 HEREFORD AYLESTONE 1 1 2 HEREFORD BELMONT 1 3 1 1 6 HEREFORD CENTRAL 1 1 1 1 4 HEREFORD CENTRAL (CITY) 6 3 3 7 4 3 26 HEREFORD HINTON 1 2 1 4 HEREFORD HOLMER 2 1 4 7 HEREFORD ST. MARTINS 2 3 1 3 3 2 14 HEREFORD ST. NICHOLAS 1 1 2 HEREFORD THREE ELMS 2 2 4 HOLME LACY 1 1 KILPECK 1 1 KINGSTONE 1 1 1 3 LEDBURY TOWN 1 2 1 4 LEINTWARDINE 1 1 LEOMINSTER TOWN 1 2 1 1 1 6 LINTON 1 1 LLANWARNE 1 1 LOWER BULLINGHAM 1 1 MARSTOW 1 1 2 4 PETERCHURCH 1 1 ROSS-ON-WYE TOWN 1 1 1 1 4 SOUTH BELMONT 1 1 2 WEOBLEY 1 1 WITHINGTON (E) 2 2 Herefordshire Total 21 14 16 33 16 9 109 North Worcestershire ALVECHURCH 1 1 2 ALVECHURCH BORDESELEY 1 1 ALVECHURCH HOPWOOD 1 1 BARNT GREEN 1 1 BEACON RUBERY TOWN 2 2 BEOLEY 1 1 1 1 4 BEWDLEY 1 1 2 CATSHILL 2 1 3 1 7 CHARFORD 2 2 2 6 CHURCH HILL NORTH 1 3 1 2 7 CHURCH HILL SOUTH 4 1 2 2 9 COFTON HACKETT 1 1 2 DRAKES CROSS 2 2 DRAKES CROSS HOLYWOOD 1 1 FRANKLEY 1 1 HAGLEY 2 1 3 KIDDERMINSTER FOLEY PARK 1 1 2 KIDDERMINSTER AGGBOROUGH HOOBROOK 1 1 KIDDERMINSTER AGGBOROUGH TOWN CENTRE 3 6 3 5 4 21 KIDDERMINSTER BROADWATERS 1 4 1 6 KIDDERMINSTER FRANCHE 2 1 3 KIDDERMINSTER GREENHILL 5 4 2 11 KIDDERMINSTER HABBERLEY/BLAKEBROOK 1 1 1 3 KIDDERMINSTER OFFMORE 2 3 1 1 1 8 KIDDERMINSTER OLDINGTON 1 1 KIDDERMINSTER SPENNELLS 1 1 2 2 6 KIDDERMINSTER SUTTON PARK