Evaluation of Techniquest and Techniquest Glyndŵr School Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amgueddfa Cymru: Inspiring Wales Contents

Amgueddfa Cymru: Inspiring Wales contents your national museums 3 introduction: bringing our museums to life 5 bringing the past to life 7 understanding our landscape 9 beyond buildings 11 reaching out 13 celebrating learning 15 highlights 19 supporters and donors 23 Published in 2010 by Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales Cathays Park, Cardiff, CF10 3NP, Wales. © the National Museum of Wales Text: Heledd Fychan Editing and production: Mari Gordon Design: A1 Design, Cardiff Printed by: Zenith Media All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the National Museum of Wales, or the copyright owner(s), or as expressly permitted by law. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Department, National Museum Cardiff, CARDIFF CF10 3NP. Printed on Challenger White Pulpboard made from ECF pulp from sustainable forests. Inspiring Wales Inspiring Wales 1 National Museum Cardiff Discover art, archaeology, natural history and geology. Explore our past in Origins: In Search of Early Wales, enjoy works from one of the finest art collections in Europe, find out how life evolved in Wales and which your national museums dinosaurs roamed the land. Entry is free to Wales’s seven national museums The National Roman Legion Museum The Museum lies within the ruins of the Roman fortress and offers the only remains of a roman legionary barracks on view anywhere in Europe plus Britain’s most complete amphitheatre. -

Wales Gene Park Education & Engagement

2016 Wales Gene Park Education & Engagement Established in 2002, the Wales Gene Park continues to operate in a field of fast developing technologies and rapidly emerging opportunities for their application. Going forward into the second decade since the first release of the human genome sequence, we want to ensure that researchers in Wales are in a position to meet the challenges and opportunities presented by human genetics and genomics and that our health practitioners can use new genetic and genomic knowledge to prevent, better diagnose and better treat human illness. To do this the Wales Gene Park provides technology and expertise, trains and supports researchers and engages with and educates professionals and the public. This broad portfolio of activity is undertaken by an able and enthusiastic team without which the high standard of genetic research and education in Wales would be unsustainable. Education & Engagement Programme The Wales Gene Park delivers an innovative and continually developing annual programme of Education & Engagement events. Continuing professional development is provided for health care professionals through a range of conferences, seminars and workshops on all aspects of genetics. These events provide information about the latest advances in genetics to further the education and training of these professionals and keep them up to date with this rapidly changing field. For teachers, we provide continuing professional development on the social and ethical issues surrounding gene technology and research-based topics. We also have a Teachers’ Genetics Network with over 400 members who receive a termly newsletter containing genetics-related news and information. For students we hold a 6th Form Conference and a Genetics Roadshow on alternate years as well as organising one off events such the interactive dramas ‘Boy Genius’ and ‘Meet the Mighty Gene Machine’ and also consultation sessions and discussions throughout the year. -

Prospectus Cardiff.Ac.Uk

2022 Cardiff University Undergraduate Prospectus cardiff.ac.uk 1 Welcome from a leading university . We are proud to be Wales’ only Croeso Russell (Croy-so - Welcome) Group University “Cardiff has a good reputation. I remember An international being amazed by the university, with facilities here and students from excited by the amount of choice you are more than given when it came to 120 countries selecting modules.” Phoebe, Biomedical Sciences, 2020 Driven by creativity and curiosity, Top 5 we strive to fulfil UK University our social, cultural and economic for research obligations to quality Cardiff, Wales Source: Research Excellence Framework, and the world. see page 18 2 Welcome Hello! I’m pleased to introduce you to Cardiff University. Choosing the right university is a major decision and it’s important that you choose the one that is right for you. Our prospectus describes what it is like to be an undergraduate at Cardiff University in the words of the people who know it best - our students, past and present, and staff. However, a prospectus can only go so far, and the best way to gain an insight into life at Cardiff University is to visit us and experience it for yourself. Whatever your choice, we wish you every success with your studies. Professor Colin Riordan 97% President and Vice-Chancellor of our graduates were in employment and/or further Contents study, due to start a new job or course, or doing Reasons to love Cardiff 4 Students from around the world 36 other activities such as A capital city 8 travelling, 15 months after Location – campus maps 38 A leading university 12 the end of their course.* Degree programmes Building a successful Source: Higher Education Statistics Agency, by Academic School 40 latest Graduate Outcomes Survey 2017/18, university 16 published by HESA in June 2020. -

WISERD Annual Conference 2016

#WISERD2016 WISERD Annual Conference 2016 WISERD Annual Conference 2016 Abstract Booklet 13th and 14th July 2016 Swansea University #WISERD2016 @WISERDNews 1 WISERD Annual Conference 2016 #WISERD2016 DAY 1: Wednesday 13 July Welcome: 9.30am Ian Rees Jones, Director Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods (WISERD) Ian Rees Jones was appointed Professor of Sociological Research at Cardiff University in 2012 and is currently the Director of the Wales Institute for Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods (WISERD). He is interested in theoretical and empirical work on social change and processes of social change. He is currently engaged in a series of research projects that addresses processes of social change and their impact on individuals, institutions, communities and civil society. He is also undertaking research specifically addressing ageing, later life and the experience of dementia. This includes work looking at class and health inequalities in later life, generational relations, social engagement and participation and changes in consumption patterns as people age. He is a Fellow of the Learned Society of Wales and Fellow of the UK Academy of Social Sciences. 2 #WISERD2016 WISERD Annual Conference 2016 Welcome Address: The Right Honourable Rhodri Morgan Chancellor of Swansea University The Services/Manufacturing Balance and the Welsh Economic Recovery The Right Honourable Rhodri Morgan was the First Minister for Wales from 2000-2009. He was educated at St John’s College Oxford and Harvard University. After working as the Industrial Development Officer for South Glamorgan County Council from 1974 to 1980 he became Head of the European Commission Office in Wales form 1980 to 1987. -

Degree Apprenticeship Provision 2019/20

Degree Apprenticeship Provision 2019/20 Awarding body Delivery provider Pathway Qualification Contact Weblink Under Development Professor Tim Woods, Pro Vice-Chancellor www.aber.ac.uk [email protected] 01970 622009 (No page available for degree apprenticeships at this time) Aberystwyth University Judith Shepherd – Project lead Deputy Registrar for Academic Partnerships [email protected] 01970 622287 www.bangor.ac.uk/courses/undergraduate/H300-Applied-Software- Bangor and Grŵp Llandrillo Menai Software BSc Applied Software Engineering (Hons) Admissions Tutor Engineering-Degree-Apprenticeship Bangor and Grŵp Llandrillo Menai Cyber BSc Applied Cyber Security (Hons) 01248 382686 [email protected] Bangor University Bangor and Grŵp Llandrillo Menai Data BSc Applied Data Science (Hons) or Bangor and Grŵp Llandrillo Menai Engineering Product Design and Development BEng Hons Applied Engineering Systems (Mechanical) [email protected] Bangor and Grŵp Llandrillo Menai Engineering Product Design and Development BEng Hons Applied Engineering Systems (Electrical / Electronic) www.cardiffmet.ac.uk/business/cwbl/Pages/Higher- Direct Data BSc (Hons) Applied Data Science Centre for Work Based Learning Team: Apprenticeships.aspx Cardiff Metropolitan University 029 2041 6037 or 029 2020 5511 [email protected] Cardiff and Gower College Swansea Engineering Product Design and Development BEng (Hons) Integrated Engineering IT/Software Engineering: www.cardiff.ac.uk/ Direct Software BSc Applied Software Engineering Degree Apprenticeship Matthew -

Cardiff Meetings & Conferences Guide

CARDIFF MEETINGS & CONFERENCES GUIDE www.meetincardiff.com WELCOME TO CARDIFF CONTENTS AN ATTRACTIVE CITY, A GREAT VENUE 02 Welcome to Cardiff That’s Cardiff – a city on the move We’ll help you find the right venue and 04 Essential Cardiff and rapidly becoming one of the UK’s we’ll take the hassle out of booking 08 Cardiff - a Top Convention City top destinations for conventions, hotels – all free of charge. All you need Meet in Cardiff conferences, business meetings. The to do is call or email us and one of our 11 city’s success has been recognised by conference organisers will get things 14 Make Your Event Different the British Meetings and Events Industry moving for you. Meanwhile, this guide 16 The Cardiff Collection survey, which shows that Cardiff is will give you a flavour of what’s on offer now the seventh most popular UK in Cardiff, the capital of Wales. 18 Cardiff’s Capital Appeal conference destination. 20 Small, Regular or Large 22 Why Choose Cardiff? 31 Incentives Galore 32 #MCCR 38 Programme Ideas 40 Tourist Information Centre 41 Ideas & Suggestions 43 Cardiff’s A to Z & Cardiff’s Top 10 CF10 T H E S L E A CARDIFF S I S T E N 2018 N E T S 2019 I A S DD E L CAERDY S CARDIFF CAERDYDD | meetincardiff.com | #MeetinCardiff E 4 H ROAD T 4UW RAIL ESSENTIAL INFORMATION AIR CARDIFF – THE CAPITAL OF WALES Aberdeen Location: Currency: E N T S S I E A South East Wales British Pound Sterling L WELCOME! A90 E S CROESO! Population: Phone Code: H 18 348,500 Country code 44, T CR M90 Area code: 029 20 EDINBURGH DF D GLASGOW M8 C D Language: Time Zone: A Y A68 R D M74 A7 English and Welsh Greenwich Mean Time D R I E Newcastle F F • C A (GMT + 1 in summertime) CONTACT US A69 BELFAST Contact: Twinned with: Meet in Cardiff team M6 Nantes – France, Stuttgart – Germany, Xiamen – A1 China, Hordaland – Norway, Lugansk – Ukraine Address: Isle of Man M62 Meet in Cardiff M62 Distance from London: DUBLIN The Courtyard – CY6 LIVERPOOL Approximately 2 hours by road or train. -

Fees Charged for GCSE and AS/A Level Qualifications in Wales (To 2017/18) Report for Qualifications Wales

Fees charged for GCSE and AS/A level qualifications in Wales (to 2017/18) Report for Qualifications Wales November 2018 About LE Wales LE Wales is consultancy providing economic and policy advice to clients based in Wales, and is a trade name of London Economics Limited. London Economics is a leading economics consultancy specialising in public policy economics. Our consultants offer a comprehensive range of skills, covering all aspects of economic and financial analysis and policy development. w: www.le-wales.co.uk e: [email protected] t: +44 (0)2920 660 250 Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the useful guidance and feedback provided by Stefanie Taylor, Tom Anderson and Emyr George from Qualifications Wales throughout this research. Qualifications Wales also provided us with much of the data that was employed in our analysis. We would also like to thank the main awarding bodies in England and Wales for their assistance with the collation of fees data. Responsibility for the contents of this report remains with LE Wales. Authors Siôn Jones, Wouter Landzaat and Viktoriya Peycheva Wherever possible LE Wales uses paper sourced from sustainably managed forests using production processes that meet the EU Ecolabel requirements. Table of Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Services and fees related to general qualifications 4 3 Entry fees 7 4 Post-results service fees 34 5 Continuing professional development (CPD) fees 41 6 Other fees 43 Index of Figures 45 LE Wales Fees charged for GCSE and AS/A level qualifications in Wales (to 2017/18) i 1 | Introduction 1 Introduction 1.1 Context Following the Welsh Government’s review of qualifications for 14-19-year-olds in 2012, GCSEs and A levels in Wales have been reformed. -

Press Release

Press release Date: Friday, 9 November 2007 Title: New Welsh Beacon to bring universities and public closer People in Wales will be able to play a much more interactive role in the work of higher education institutions thanks to a collaborative partnership of leading Welsh organisations. Cardiff University, University of Glamorgan, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, Techniquest and BBC Wales have come together and successfully bid to become Wales’ only Beacon for Public Engagement, and will now lead Welsh universities in working more closely with the public. The Beacon for Wales will encourage universities to make wider contributions to society by engaging communities more fully in their work and is part of the biggest initiative of its kind ever launched in the UK. A total of six beacons are to be set up, including others in Manchester, Newcastle, Norwich, London, and Edinburgh. There will also be a UK-wide co-ordinating centre based in Bristol, which will work across the initiative to promote best practice and provide a single point of contact for the whole higher education sector. The Beacon for Wales was chosen from 87 bidders from around the UK, and will share in a £9.2M funding pot over four years. Acting as a catalyst for other higher education institutions across Wales, the Beacon for Wales will open up opportunities for people outside academic communities to better understand, support and challenge research undertaken in universities. Professor Ken Woodhouse, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Engagement at Cardiff University, the lead partner in the Beacon for Wales, said: “This initiative will ensure that the public has a greater understanding of the work of higher education institutions, as well as making sure our universities understand how the public feels about issues ranging from science, business and the arts, to language, the environment, history and health. -

Gce Teachers' Guide

GCE TEACHERS’ GUIDE New Specifications: for teaching from September 2010 Government & Politics GCE AS and A GOVERNMENT & POLITICS Teachers' Guide 1 Contents GCE AS and A Level Government and Politics Teachers' Guide Page 1. Introduction 3 1.1 - Rationale 4 1.2 - Overview of the Specification 4 2. Delivering the specification 5 2.1 - Unit Descriptions 6 2.2 - Pathways through the Specification 19 2.3 - AS - An example of one possible pathway 20 through the AS Level Specification 2.4 A2 - An example of one possible pathway 31 through the A2 Level Specification 3. Support for Teachers 43 3.1 - Generic Resources for the Specification as a whole 43 3.2 - Specific Resources 44 3.3 - National Grid for Learning – Cymru 58 4. Assessment Guidance 59 5. Advice for Candidates 63 Appendices 65 A Vocabulary List / Geirfa Llywodraeth a Gwleidyddiaeth 65 GCE AS and A GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS Teachers' Guide 3 1. INTRODUCTION The WJEC AS and A2 Government and Politics Specification is designed to support the course for delivery from September 2009. The first AS awards were made in summer 2009 and the first A level awards in summer 2010. The specification can be delivered and assessed in centres in Wales only. This Guide is one of a number of ways in which the WJEC provides assistance to teachers delivering the new specification. Also essential to its introduction are the Specimen Assessment Materials (question papers and marking schemes) and professional development (CPD) conferences. Other provision which you will find useful is: • Examiners' reports on each examinations series • Free access to past question papers via the WJEC secure website • Easy access to specification and other key documents on main website • Itemised feedback on outcomes for candidates at question level • Regular CPD delivered by Chief Examiners • Easy access to both the Subject Officer and to administrative sections for individual support, help and advice. -

Staff at Further Education Institutions in Wales, 2017/18

Staff at Further Education Institutions in 24 May 2019 Wales 2017/18 SFR 35/2019 Key points About this release During 2017/18, staff numbers directly employed by further education This statistical first (FE) institutions in Wales amounted to 8,520 full time equivalents (FTEs). release provides Chart 1: Full-Time Equivalent Staff Numbers by pay expenditure information on the category, 2012/13 to 2017/18 number of full time equivalent (FTE) staff 10,000 (including work-based 8,000 learning and adult community learning) 6,000 directly employed by further education 4,000 institutions at any time during the academic year 2,000 Staff numbers Staff 2017/18. The data used in this release were 0 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 collected from the Teaching and Learning Departments Teaching and Learning Support Services institutions by the Welsh Other Support Services Administration and Central Services Government via the Other Finance Record. Additional detail is The overall number of FTE staff directly employed by FE institutions in available on the Welsh Wales rose by 6 per cent between 2016/17 and 2017/18. Government's interactive There were increases in FTE staff numbers in 8 of the 13 FE institutions data dissemination to varying degrees but most notably at Cardiff and Vale College, where service StatsWales. there was an increase of 340 FTE staff (a 40 per cent increase). This was In this release due to the acquisition of two work-based learning training providers during By institution 2 2016/17 and 2017/18. -

108-20 February 2020.Pub

CREIGIAU 23 50TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION EXCITING TIME FOR MEMORIAL PARK! Creigiau 23 held it’s 50th Anniversary Dinner at the Hilton Hotel Cardiff on Saturday 16th December. It was attended by one hundred and sixty people including members, ex members, guests, wives and partners. It was joy to see three of the original members as guests in the audience, including Mr. Arwel Ellis- Owen, the first ever speaker. The philanthropic society was formed back in 1969 after an independent group of twenty three local gentlemen met at the Creigiau Inn. It has recently become a registered charity in it’s own right. Work is now complete on the first phase of improvements - we hope you like it so far. The weather has been terrible; it will take some time for the grass to fully recover around the new units, so please take care and try to avoid the muddy areas. Thanks to everyone who has made this happen, and to PCC for their support with this project. We still have more work to do, so watch this space for further news, and keep an eye on our social media. Speeches were given by two local [email protected] residents, after dinner speaker CREIGIAU HAS A Facebook: PentyrchMemorialPark Kevan Eveleigh and the much WORLD CUP CRICKETER Twitter @PentyrchPark respected Gabe Treharne, a Pro THANK YOU FOR HELPING Chancellor of Cardiff University. Pentyrch Community Council would Mr.Eveleigh brought tears to the eyes like to thank all the residents and co with an eloquent and humorous -ordinators who have made speech that mentioned members and donations and worked tirelessly speakers past and present. -

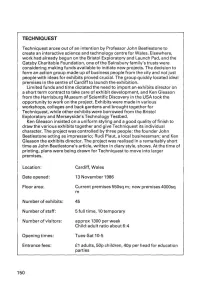

Techniquest: Professor John Beetlestone

TECHIMIQUEST Techniquest arose out of an intention by Professor John Beetlestone to create an interactive science and technology centre for Wales. Elsewhere, work had already begun on the Bristol Exploratory and Launch Pad, and the Gatsby Charitable Foundation, one ofthe Sainsbury family's trusts were considering making funds available to initiate new projects. The decision to form an action group made up of business people from the city and not just people with ideas for exhibits proved crucial. The group quickly located ideal premises in the centre of Cardiff to launch the exhibition. Limited funds and time dictated the need to import an exhibits director on a short term contract to take care of exhibit development, and Ken Gleason from the Harrisburg Museum of Scientific Discovery in the USA took the opportunity to work on the project. Exhibits were made in various workshops, colleges and back gardens and brought together for Techniquest, while other exhibits were borrowed from the Bristol Exploratory and Merseyside's Technology Testbed. Ken Gleason insisted on a uniform styling and a goodqualityof finish to draw the various exhibits together and give Techniquest its individual character. The project was controlled by three people: the founder John Beetlestone acting as impressario; Rudi Plaut, a local businessman; and Ken Gleason the exhibits director. The project was realised in a remarkably short time as John Beetlestone's article, written in diary style, shows. At the time of printing, plans were being drawn for Techniquest to move into larger premises. Location: Cardiff, Wales Date opened: 13 November 1986 Floor area: Current premises 550sq m; new premises 4000sq m Number of exhibits: 45 Number of staff: 5 full time, 10 temporary Number of visitors: approx 1300 per week Child:adult ratio about 6:4 Opening times: Tues-Sat10-5 Entrance fees: £1 adults, 50p children, 40p per head for education parties 150 TECHNIQUEST John Beetlestone Professor Beetlestone is a 'lapsed' chemist.