Why Do the Rich Save So Much?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preview Chapter 7: a Few Good Women

7 A Few Good Women Zhou Qunfei grew up poor in Hunan Province, where she worked on her family’s farm to help support her family. Later, while working at a factory in Guangdong Province, she took business and computer courses at Shen- zhen University. She started a company with money she saved working for a watch producer. In 2015 she was the world’s richest self-made woman, with a fortune of $5.3 billion, according to Forbes. Her wealth comes from her company, Lens Technology, which makes touchscreens. It employs 60,000 people and has a market capitalization of nearly $12 billion. Lei Jufang was born in Gansu Province, one of the poorest areas of northwest China. After studying physics at Jiao Tong University, she cre- ated a new method for vacuum packaging food and drugs, which won her acclaim as an assistant professor. On a trip to Tibet she became fascinated by herbal medicines. In 1995 she founded a drug company, Cheezheng Tibetan Medicine, harnessing her skill in physics and engineering to exploit the untapped market for Tibetan medicine. Her company has a research institute and three factories that produce herbal healing products for con- sumers in China, Malaysia, Singapore, and North and South America. She has amassed a fortune of $1.5 billion. In most countries, women get rich by inheriting money. China is dif- ferent: The majority of its women billionaires are self-made. Zhou Qunfei and Lei Jufang are unusual because they established their own companies. Most of the eight Chinese female self-made company founders worth more than $1 billion made their money in real estate or in companies founded jointly with husbands or brothers. -

Political Capture and Economic Inequality

178 OXFAM BRIEFING PAPER 20 JANUARY 2014 Housing for the wealthier middle classes rises above the insecure housing of a slum community in Lucknow, India. Photo: Tom Pietrasik/Oxfam WORKING FOR THE FEW Political capture and economic inequality Economic inequality is rapidly increasing in the majority of countries. The wealth of the world is divided in two: almost half going to the richest one percent; the other half to the remaining 99 percent. The World Economic Forum has identified this as a major risk to human progress. Extreme economic inequality and political capture are too often interdependent. Left unchecked, political institutions become undermined and governments overwhelmingly serve the interests of economic elites to the detriment of ordinary people. Extreme inequality is not inevitable, and it can and must be reversed quickly. www.oxfam.org SUMMARY In November 2013, the World Economic Forum released its ‘Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014’, in which it ranked widening income disparities as the second greatest worldwide risk in the coming 12 to 18 months. Based on those surveyed, inequality is ‘impacting social stability within countries and threatening security on a global scale.’ Oxfam shares its analysis, and wants to see the 2014 World Economic Forum make the commitments needed to counter the growing tide of inequality. Some economic inequality is essential to drive growth and progress, rewarding those with talent, hard earned skills, and the ambition to innovate and take entrepreneurial risks. However, the extreme levels of wealth concentration occurring today threaten to exclude hundreds of millions of people from realizing the benefits of their talents and hard work. -

The Influence of the Los Angeles ``Oligarchy'' on the Governance Of

The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” onthe governance of the municipal water department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service? Fionn Mackillop To cite this version: Fionn Mackillop. The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” on the governance of the municipal wa- ter department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service?. Business History Conference Online, 2004, 2, http://www.thebhc.org/publications/BEHonline/2004/beh2004.html. hal-00195980 HAL Id: hal-00195980 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00195980 Submitted on 11 Dec 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Influence of the Los Angeles “Oligarchy” on the Governance of the Municipal Water Department, 1902- 1930: A Business Like Any Other or a Public Service? Fionn MacKillop The municipalization of the water service in Los Angeles (LA) in 1902 was the result of a (mostly implicit) compromise between the city’s political, social, and economic elites. The economic elite (the “oligarchy”) accepted municipalizing the water service, and helped Progressive politicians and citizens put an end to the private LA City Water Co., a corporation whose obsession with financial profitability led to under-investment and the construction of a network relatively modest in scope and efficiency. -

Democracy & Philanthropy

DEMOCRACY & PHILANTHROPY The Rockefeller Foundation and the American Experiment the rockefeller foundation centennial series democracy & philanthropy the rockefeller foundation and the american experiment By Eric John Abrahamson Sam Hurst Barbara Shubinski Innovation for the Next 100 Years Rockefeller Foundation Centennial Series 2 Chapter _: Democracy & Philanthropy 3 4 Chapter _: Democracy & Philanthropy 5 6 Chapter _: Democracy & Philanthropy 7 8 Chapter _: Democracy & Philanthropy 9 Preface from Dr. Judith Rodin 14 Foreword – Justice Sandra Day O'Connor 18 1 The Charter Fight 24 11 Government by Experts 52 111 Philanthropy at War 90 © 2013 by Rockefeller Foundation have been deemed to be owned by 1v The Arts, the Humanities, The Rockefeller Foundation Centennial Series the Rockefeller Foundation unless we and National Identity 112 Foreword copyright Justice Sandra Books published in the Rockefeller were able to determine otherwise. Day O’Connor Foundation Centennial Series provide Specific permission has been granted All rights reserved. case studies for people around the by the copyright holder to use the v Foundations Under Fire 144 world who are working “to promote the following works: well-being of humankind.” Three books Top: Rockefeller Archive Center Equal Opportunity for All 174 Bottom: John Foxx. Getty Images. highlight lessons learned in the fields Ruthie Abel: 8-9, 110-111 v1 of agriculture, health, and philanthropy. Art Resource: 26 Three others explore the Foundation’s Book design by Pentagram. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of v11 Democracy and Design work in Africa, Thailand, and the United Public Health: 57 States. For more information about Democracy & Philanthropy: Department of Special Collections in America's Cities 210 the Rockefeller Foundation Centennial and University Archives, Marquette The Rockefeller Foundation and initiatives, visit http://centennial. -

Jan Sobieski's Latifundium and the Soldiers (1652-1696)

Open Military Studies 2020; 1: 62–69 Research Article Magdalena Ujma* Jan Sobieski’s latifundium and the soldiers (1652-1696) https://10.1515/openms-2020-0105 Received Oct 26, 2020; accepted Nov 07, 2020 Abstract: An analysis of the relationship between Jan III Sobieski and the people he distinguished shows that there were many mutual benefits. Social promotion was more difficult if the candidate for the office did not come from a senatorial family34. It can be assumed that, especially in the case of Atanazy Walenty Miączyński, the economic activity in the Sobieski family was conducive to career development. However, the function of the plenipotentiary was not a necessary condition for this. Not all the people distinguished by Jan III Sobieski achieved the same. More important offices were entrusted primarily to Marek Matczyński. Stanisław Zygmunt Druszkiewicz’s career was definitely less brilliant. Druszkiewicz joined the group of senators thanks to Jan III, and Matczyński and Szczuka received ministerial offices only during the reign of Sobieski. Jan III certainly counted on the ability to manage a team of people acquired by his comrades-in-arms in the course of his military service. However, their other advantage was also important - good orientation in political matters and exerting an appropriate influence on the nobility. The economic basis of the magnate’s power is an issue that requires more extensive research. This issue was primarily of interest to historians dealing with latifundia in the 18th century. This was mainly due to the source material. Latifundial documentation was kept much more regularly in the 18th century than before and is well-organized. -

The Men Who Built America

“THE AMERICAN ECONOMY WAS LINKED BY RAILROADS, FUELED BY OIL AND BUILT BY STEEL.” Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Episode 1: A New WAR BEGINS J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford – their names are synonymous with As the nation attempts to rebuild following the destruction of the innovation, big business and the American Dream. These leaders Civil War, Cornelius Vanderbilt is the first to see the need for unity sparked incredible advances in technology while struggling to to regain America’s stature in the world. Vanderbilt makes his mark consolidate their industries and rise to the top in shipping and then the railroad industry. Railroads stitch together of the business world. The Men Who Built America™ chronicles the the nation, stimulating the economy by making it easier to move connections between these iconic businessmen and explores the goods across the country. But Vanderbilt faces intense competition way they shaped the country, transforming the early on, showing that captains of industry will always be chal- U.S. into a global superpower in just 50 years. lenged by new innovators and mavericks. Tracing their roles in the oil, steel, railroad, auto and financial Key TERMS to DEFINE industries, this series uses stunning CGI and little-known stories to ARCHETYPE, ENTREPRENEUR, INFRASTRUCTURE, INGENUITY, examine the lives of these iconic tycoons. How did these leaders INNOVATION advance progress, and what were the costs and consequences of American industrial growth? What role did everyday Americans Discussion Questions play in this growth, and how were their voices heard? This series is an excellent companion for course units on business, American 1. -

Media Oligarchs Go Shopping Patrick Drahi Groupe Altice

MEDIA OLIGARCHS GO SHOPPING Patrick Drahi Groupe Altice Jeff Bezos Vincent Bolloré Amazon Groupe Bolloré Delian Peevski Bulgartabak FREEDOM OF THE PRESS WORLDWIDE IN 2016 AND MAJOR OLIGARCHS 2 Ferit Sahenk Dogus group Yildirim Demirören Jack Ma Milliyet Alibaba group Naguib Sawiris Konstantin Malofeïev Li Yanhong Orascom Marshall capital Baidu Anil et Mukesh Ambani Rupert Murdoch Reliance industries ltd Newscorp 3 Summary 7. Money’s invisible prisons 10. The hidden side of the oligarchs New media empires are emerging in Turkey, China, Russia and India, often with the blessing of the political authorities. Their owners exercise strict control over news and opinion, putting them in the service of their governments. 16. Oligarchs who came in from the cold During Russian capitalism’s crazy initial years, a select few were able to take advantage of privatization, including the privatization of news media. But only media empires that are completely loyal to the Kremlin have been able to survive since Vladimir Putin took over. 22. Can a politician be a regular media owner? In public life, how can you be both an actor and an objective observer at the same time? Obviously you cannot, not without conflicts of interest. Nonetheless, politicians who are also media owners are to be found eve- rywhere, even in leading western democracies such as Canada, Brazil and in Europe. And they seem to think that these conflicts of interests are not a problem. 28. The royal whim In the Arab world and India, royal families and industrial dynasties have created or acquired enormous media empires with the sole aim of magnifying their glory and prestige. -

1430-N-Broad-St-Nomination.Pdf

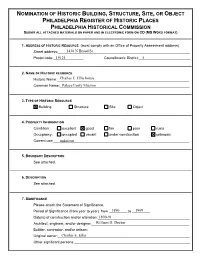

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM ON CD (MS WORD FORMAT) 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________1430 N Broad St ________ Postal code:_______________19121 Councilmanic District:_______________5 ___________ 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________Charles E. Ellis house ________ Common Name:_________________________________________________________Palace/Unity Mission ________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Condition: excellent good fair poor ruins Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:________unknown____________________________________________________ ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See attached. 6. DESCRIPTION See attached. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1890 to _________1909 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________1890-91 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________William H. Decker _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________ _________ Original owner:_________________________________________________________Charles -

Populism Or Embedded Plutocracy? the Emerging World Order

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hunter College 2019 Populism or Embedded Plutocracy? The Emerging World Order Michael Lee CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_pubs/603 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Draft: Populism or Embedded Plutocracy? Envisioning the Emerging World Order Introduction The liberal world order is in dire straits. The world of moderately open migration, free trade, and free flows of capital that has existed since the 1970s is under attack. Liberal democracies around the world have seen the rise of far-right political parties trading in xenophobia, while attacking traditional liberal institutions. Many political scientists, increasingly committed to country-specific studies, or mid-level theories of small phenomenon are picking up many of these developments, while missing common threads between them. We are bearing witness to systemic changes. After the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, the United States and its allies in the G-7 constructed a new neo-liberal world order characterized by relatively open migration, free trade, and free flows of capital.1 Today, that order is collapsing in the face of its internal contradictions. Free flows of capital, combined with the privileged position of the American dollar, saddled the global economy with recurrent financial crises. Internally, the implementation of many neoliberal policies (and creation of transnational workarounds) undermined many of the civil society groups vital for broad-based democracy. -

The Fate of Freedom in Eastern Europe: Autocracy – Oligarchy – Anarchy?

International Conference at Natolin organized by the Chair of European Civilization 22-23 September 2016 THE FATE OF FREEDOM IN EASTERN EUROPE: AUTOCRACY – OLIGARCHY – ANARCHY? The Coat of Arms of the January Rising (1863-1864) inspired by the Commonwealth of Three Nations agreed by the Union of Hadiach The aim of the conference is to ask whether the region between the Baltic and Black Seas, provisionally described as ‘Eastern Europe’, is historically fated to experience the failure of systems of government founded on liberty; whether the only stable state structures involve autocratic or oligarchic rule; whether dreams of freedom lead either to anarchy or dictatorship. This fate seems to be expressed by narratives about post-Soviet republics, especially in the context of the last Ukrainian revolutions. Many accept such narratives, but others contest them, defending these countries’ right to self-determination. This conference will consider the sources and appeal of such narratives. Are these nations are incapable or capable of maintaining forms of statehood based on liberty? Because such narratives are popular in Russia, it would appear that one of the main reasons for this is the strength of the tradition and ideology of autocratic rule in Russia (that is, the heir of the Grand Duchy of Muscovy claiming supremacy over ‘all Rus’). So one aim of the conference is to look at periods in the history of Rus and Russia, which it seemed that liberty had a chance of bedding down. These include the medieval city republic of Novgorod the Great and 1917. The titular problem is also linked to the view, rooted in Polish, Lithuanian, Ukrainian and Belarusian historiographies, that the libertarian constitution of the Commonwealth of the Two Nations, formed in the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Polish Crown, could not be grafted into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania or Ukraine (on the banks of the Dnipro). -

Torts and Estates: Remedying Wrongful Interference with Inheritance

GOLDBERG 65 STAN. L. REV. 335.DOC (DO NOT DELETE) 1/26/2013 6:49 PM TORTS AND ESTATES: REMEDYING WRONGFUL INTERFERENCE WITH INHERITANCE John C.P. Goldberg* Robert H. Sitkoff** This Article examines the nature, origin, and policy soundness of the tort of interference with inheritance. We argue that the tort should be repudiated because it is conceptually and practically unsound. Endorsed by the Second Restatement of Torts and recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court in a recent decision, the tort has been adopted by courts in nearly half the states. But it is deeply problematic from the perspectives of both inheritance law and tort law. It undermines the core principle of freedom of disposition that undergirds American inheritance law. It invites circumvention of principled policies encoded in the specialized rules of procedure applicable in inheritance disputes. In many cases, it has displaced venerable and better-fitting causes of action for equitable relief. * Eli Goldston Professor of Law, Harvard University. ** John L. Gray Professor of Law, Harvard University. For helpful comments and suggestions, the authors thank Gregory Alexander, Mark Ascher, John Coates, Glenn Cohen, Richard Epstein, Charles Fried, Thomas Gallanis, Mark Geistfeld, Adam Hirsch, Louis Kaplow, Gregory Keating, Daniel Kelly, Michael Klarman, Diane Klein, Andrew Kull, John Langbein, Melanie Leslie, Gerald Neuman, Marilyn Ordover, Richard Posner, Mark Ramseyer, Jeffrey Schoenblum, Steve Shavell, Henry Smith, Stewart Sterk, Joshua Tate, Lawrence Waggoner, Sarah Waldeck, Benjamin Zipursky, and workshop participants at Harvard Law School, the University of Southern California Confer- ence on Property, Tort, and Private Law Theory, and the William and Mary Private Law Workshop. -

The Political Role of Business Magnates in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes

Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 2019; 60(2): 299–334 Heiko Pleines The Political Role of Business Magnates in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes. A Comparative Analysis https://doi.org/10.1515/jbwg-2019-3001 Abstract: This contribution examines the role of business magnates (“oli- garchs”) in political transitions away from competitive authoritarianism and towards either full authoritarianism or democracy. Based on 65 cases of compet- itive authoritarian regimes named in the academic literature, 24 historical cases with politically active business magnates are identified for further investigation. The analysis shows that in about half of those cases business magnates do not have a distinct impact on political regime change, as they are tightly integrated into the ruling elites. If they do have an impact, they hamper democratization at an early stage, making a transition to full democracy a rare exception. At the same time, a backlash led by the ruling elites against manipulation through business magnates makes a transition to full autocracy more likely than in competitive authoritarian regimes without influential business magnates. JEL-Codes: D 72, D 74, N 40, P 48 Keywords: Business magnates, economic elites, political regime trajectories, competitive authoritarianism, Großunternehmer, Wirtschaftseliten, Entwick- lungspfade politischer Regime 1 Introduction Wealthy businesspeople who are able to influence political decisions acting on their own are in many present and historical cases treated as “grey eminences” who hold considerable political power. While it is obvious that they influence specific policies, their impact on political regime change is less clear. This ques- tion is especially relevant for so-called “soft”, i.e. electoral or competitive au- || Heiko Pleines, (Prof.