Democracy & Philanthropy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preview Chapter 7: a Few Good Women

7 A Few Good Women Zhou Qunfei grew up poor in Hunan Province, where she worked on her family’s farm to help support her family. Later, while working at a factory in Guangdong Province, she took business and computer courses at Shen- zhen University. She started a company with money she saved working for a watch producer. In 2015 she was the world’s richest self-made woman, with a fortune of $5.3 billion, according to Forbes. Her wealth comes from her company, Lens Technology, which makes touchscreens. It employs 60,000 people and has a market capitalization of nearly $12 billion. Lei Jufang was born in Gansu Province, one of the poorest areas of northwest China. After studying physics at Jiao Tong University, she cre- ated a new method for vacuum packaging food and drugs, which won her acclaim as an assistant professor. On a trip to Tibet she became fascinated by herbal medicines. In 1995 she founded a drug company, Cheezheng Tibetan Medicine, harnessing her skill in physics and engineering to exploit the untapped market for Tibetan medicine. Her company has a research institute and three factories that produce herbal healing products for con- sumers in China, Malaysia, Singapore, and North and South America. She has amassed a fortune of $1.5 billion. In most countries, women get rich by inheriting money. China is dif- ferent: The majority of its women billionaires are self-made. Zhou Qunfei and Lei Jufang are unusual because they established their own companies. Most of the eight Chinese female self-made company founders worth more than $1 billion made their money in real estate or in companies founded jointly with husbands or brothers. -

Political Capture and Economic Inequality

178 OXFAM BRIEFING PAPER 20 JANUARY 2014 Housing for the wealthier middle classes rises above the insecure housing of a slum community in Lucknow, India. Photo: Tom Pietrasik/Oxfam WORKING FOR THE FEW Political capture and economic inequality Economic inequality is rapidly increasing in the majority of countries. The wealth of the world is divided in two: almost half going to the richest one percent; the other half to the remaining 99 percent. The World Economic Forum has identified this as a major risk to human progress. Extreme economic inequality and political capture are too often interdependent. Left unchecked, political institutions become undermined and governments overwhelmingly serve the interests of economic elites to the detriment of ordinary people. Extreme inequality is not inevitable, and it can and must be reversed quickly. www.oxfam.org SUMMARY In November 2013, the World Economic Forum released its ‘Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014’, in which it ranked widening income disparities as the second greatest worldwide risk in the coming 12 to 18 months. Based on those surveyed, inequality is ‘impacting social stability within countries and threatening security on a global scale.’ Oxfam shares its analysis, and wants to see the 2014 World Economic Forum make the commitments needed to counter the growing tide of inequality. Some economic inequality is essential to drive growth and progress, rewarding those with talent, hard earned skills, and the ambition to innovate and take entrepreneurial risks. However, the extreme levels of wealth concentration occurring today threaten to exclude hundreds of millions of people from realizing the benefits of their talents and hard work. -

Final Report of the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center Convening: October 21–23, 2015

FINAL REPORT OF THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION BELLAGIO CENTER CONVENING: OCTOBer 21–23, 2015 SUPPORTED BY FRONT COVER, FRONTISPIECE, PAGE 17, AND BACK COVER. Survivors in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone continue to face stigma, trauma, and long-term effects of the virus (AP Photo). II EFFECTIVE PUBLIC HEALTH COMMUNICATION IN AN INTERCONNECTED WORLD CONTENTS 2 Introduction – Setting the Scene: 30 Expert Insights: Key Areas Public Health Communication in an of Need and Opportunity Interconnected World 31 i. Barriers to Building Trust 4 Objectives of this Project in Public Health Communications 6 About KYNE and Ebola Deeply 36 ii. Collecting and Scaling Best Practices 7 Acknowledgments 38 iii. Managing Social Media 10 The High Stakes for Mass Public Engagement of Communication Failures 41 iv. Improving the Impact of Mainstream Media Coverage 12 How Communication Can Help or Hinder a Response 44 Developing Tools and Technology 13 i. Case Study – Ebola in West Africa: 45 i. Advanced Technology Platforms BBC Media Action 47 ii. Internet Forums and Websites 18 ii. Case Study – Managing SARS in Singapore 48 iii. Research and Knowledge Management Systems 25 iii. Case Study – Legionnaires’ Disease in New York City: The New York 50 Communications City Office of Emergency and Public Health Governance Preparedness and Response 51 i. Effective Leadership Communication 52 ii. The Role of National and Regional Governments 54 iii. Inclusive Communication at the Community Level 56 Shaping Effective Community Engagement 57 i. Conscious Community Engagement 58 ii. Communicating with Communities (CwC) 60 iii. Enhanced Partnerships with Local Media 64 Conclusion and Recommendations 67 Key Recommendations INTRODUCTION Search and rescue operations underway in Port-au-Prince on January 15, 2010 (Photo by IFRC/Eric Quintero via Flickr). -

The Influence of the Los Angeles ``Oligarchy'' on the Governance Of

The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” onthe governance of the municipal water department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service? Fionn Mackillop To cite this version: Fionn Mackillop. The influence of the Los Angeles “oligarchy” on the governance of the municipal wa- ter department (1902-1930): a business like any other or a public service?. Business History Conference Online, 2004, 2, http://www.thebhc.org/publications/BEHonline/2004/beh2004.html. hal-00195980 HAL Id: hal-00195980 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00195980 Submitted on 11 Dec 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Influence of the Los Angeles “Oligarchy” on the Governance of the Municipal Water Department, 1902- 1930: A Business Like Any Other or a Public Service? Fionn MacKillop The municipalization of the water service in Los Angeles (LA) in 1902 was the result of a (mostly implicit) compromise between the city’s political, social, and economic elites. The economic elite (the “oligarchy”) accepted municipalizing the water service, and helped Progressive politicians and citizens put an end to the private LA City Water Co., a corporation whose obsession with financial profitability led to under-investment and the construction of a network relatively modest in scope and efficiency. -

John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) Topic Guide for Chronicling America (

John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) Topic Guide for Chronicling America (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov) Introduction John D. Rockefeller was an oil industry tycoon and philanthropist who lived in Cleveland, Ohio. Born in New York in 1839, he moved with his family to northeast Ohio in 1853. At age sixteen, he began his involvement with the business world as an assistant bookkeeper for a produce commission business. He soon began his own produce commission company before joining the oil refinery industry in 1863. He established Standard Oil of Ohio in 1870, and this is where he made most of his wealth. By 1878, the company controlled 90% of all U.S. oil refineries (it was declared a trust by the U.S government in 1911). In addition to his business interests, Rockefeller regularly donated a portion of his income to charities supporting education and public health. Rockefeller died in 1937 and is buried in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland. He is widely recognized as the wealthiest American of all time. Important Dates . July 8, 1839: John Davison Rockefeller is born in Richford, New York. 1853: The Rockefeller family moves to Strongsville, a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. 1863: Rockefeller and business partner Maurice B. Clark build an oil refinery in “The Flats” area of Cleveland. 1864: Rockefeller marries Laura Celestia “Cettie” Spelman. January 10, 1870: Standard Oil of Ohio is formed and grows rapidly over the next decade, eventually forming a monopoly. 1903: Rockefeller’s General Education Board is founded. 1911: U.S. Supreme Court declares that Standard Oil Company of New Jersey is a trust, and it is broken into subsidiaries. -

K-12 NATIONAL TESTING ACTION PROGRAM (NTAP) Connecting Schools with the Nation’S Leading Testing Companies to Safely Reopen TABLE of CONTENTS

K-12 NATIONAL TESTING ACTION PROGRAM (NTAP) Connecting schools with the nation’s leading testing companies to safely reopen TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and current K-12 landscape 7 Successful programs: testing works to keep schools safer 12 K-12 National Testing Action Program: overview 24 K-12 National Testing Action Program: logistics 39 Appendix and references 53 2 CONTEXT The K-12 National Testing Action Program (NTAP) is a plan to provide free Covid-19 testing for K-12 public schools to enable safe in-person learning Situation Complication Question Answer • Due to Covid-19, a • Teachers, students and • How do we safely and 1. Implementation of full majority of US K-12 communities may fear the spread sustainably re-open the safety and mitigation public schools are of Covid-19 in schools nation’s K-12 public activities operating remotely or in • Schools are not fully equipped to schools as quickly as hybrid learning 2. Prioritized vaccination provide necessary mitigation possible? for teachers and staff • Online learning is not an measures including testing • How do we make testing 3. Weekly testing for adequate replacement • While testing capacity exists, labs free, easy and widely for in-person school and students, teachers and do not have a clear signal on how available for schools? staff is creating large to make capacity readily education and available to schools socialization gaps • The value of testing is getting lost amid the focus on vaccination 3 K-12 NATIONAL TESTING ACTION PROGRAM (NTAP) SUMMARY (1 OF 2) The school changes -

Tackling the Dual Economic and Public Health Crises Caused by COVID-19 in Baltimore Early Lessons from the Baltimore Health Corps Pilot

Tackling the Dual Economic and Public Health Crises Caused by COVID-19 in Baltimore Early Lessons from the Baltimore Health Corps Pilot Embargoed until 12:01am EDT, Tuesday, April 21, 2020June 2021 TACKLING THE DUAL ECONOMIC AND PUBLIC HEALTH CRISES CAUSED BY COVID-19 IN BALTIMORE I This report is based on research funded Authors by a consortium of donors Dylan H. Roby, Ph.D. All views expressed are solely those of the authors Neil J. Sehgal, Ph.D., M.P.H. Elle Pope, M.P.H. Melvin Seale, M.A., D.HSc Suggested citation: Roby DH, Sehgal NJ, Evan Starr, Ph.D. Pope E, Seale M, Starr E. 2021. Tackling the Dual Economic and Public Health Crises Caused by COVID- Department of Health Policy and Management 19 in Baltimore: Early Lessons from the Baltimore Health Systems and Policy Research Lab Health Corps Pilot. Prepared for the Baltimore City University of Maryland School of Public Health Health Department by the University of Maryland healthpolicy.umd.edu Health Systems and Policy Research Lab. University of Maryland School of Public Health TACKLING THE DUAL ECONOMIC AND PUBLIC HEALTH CRISES CAUSED BY COVID-19 IN BALTIMORE 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgment 3 Preface 4 Acronyms and Abbreviations 6 Executive Objectives and Early Findings 9 Summary Conclusions and Recommendations 11 Background BHC's theory of change 15 Evidence Base Supporting the BHC Pilot Model 17 Local Context 19 Creation of the BHC 20 Objectives Identifying Partners for Key Functional Roles 23 and Activities Organizational Structure 26 Early Objective 1 – Workforce Development -

Jan Sobieski's Latifundium and the Soldiers (1652-1696)

Open Military Studies 2020; 1: 62–69 Research Article Magdalena Ujma* Jan Sobieski’s latifundium and the soldiers (1652-1696) https://10.1515/openms-2020-0105 Received Oct 26, 2020; accepted Nov 07, 2020 Abstract: An analysis of the relationship between Jan III Sobieski and the people he distinguished shows that there were many mutual benefits. Social promotion was more difficult if the candidate for the office did not come from a senatorial family34. It can be assumed that, especially in the case of Atanazy Walenty Miączyński, the economic activity in the Sobieski family was conducive to career development. However, the function of the plenipotentiary was not a necessary condition for this. Not all the people distinguished by Jan III Sobieski achieved the same. More important offices were entrusted primarily to Marek Matczyński. Stanisław Zygmunt Druszkiewicz’s career was definitely less brilliant. Druszkiewicz joined the group of senators thanks to Jan III, and Matczyński and Szczuka received ministerial offices only during the reign of Sobieski. Jan III certainly counted on the ability to manage a team of people acquired by his comrades-in-arms in the course of his military service. However, their other advantage was also important - good orientation in political matters and exerting an appropriate influence on the nobility. The economic basis of the magnate’s power is an issue that requires more extensive research. This issue was primarily of interest to historians dealing with latifundia in the 18th century. This was mainly due to the source material. Latifundial documentation was kept much more regularly in the 18th century than before and is well-organized. -

Accelerating National Genomic Surveillance

Accelerating National Genomic Surveillance Unfortunately, right now, the United States and most Foreword of the rest of the world are in no better position to stop a variant from going global today than they were before the pandemic started. Currently, only a handful One secret weapon has helped beat every disease of countries have analyzed more than 5 percent of outbreak over the last century; but it is not masks their Covid-19 cases. In the United States, most local- or social distancing, lockdowns, or even vaccines. ities are sequencing less than 1 percent of cumulative Instead it is data. Data tells us which masks work, cases. What little genomic data we are collecting, how far is far enough to socially distance, whether is not being analyzed or shared fast enough to help lockdowns are necessary or even working, and who public health authorities and scientists make informed is immune. In all, data is what moves us from a pan- decisions about relaxing precautions or adapting ic-driven response to a science-driven one, telling us vaccines and treatments. how to fight back and which tools are best. This report—based on a recent convening of scien- Too often, however, the world learns to value data tists, lab administrators, public health officials, and too late and at too high of a cost. When I oversaw the entrepreneurs—provides a blueprint for dramatically U.S. response to the West African Ebola crisis, we expanding genomic surveillance in the United States. began with incomplete data and did not gain ground By amplifying warning signals and sharing information until we could better understand the basics: who was and best practices, the system presented here could positive and where? As Covid-19 swept the world one save countless lives and billions of dollars by help- year ago, many countries, including the United States, ing to forestall new variant-driven surges. -

The Men Who Built America

“THE AMERICAN ECONOMY WAS LINKED BY RAILROADS, FUELED BY OIL AND BUILT BY STEEL.” Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Episode 1: A New WAR BEGINS J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford – their names are synonymous with As the nation attempts to rebuild following the destruction of the innovation, big business and the American Dream. These leaders Civil War, Cornelius Vanderbilt is the first to see the need for unity sparked incredible advances in technology while struggling to to regain America’s stature in the world. Vanderbilt makes his mark consolidate their industries and rise to the top in shipping and then the railroad industry. Railroads stitch together of the business world. The Men Who Built America™ chronicles the the nation, stimulating the economy by making it easier to move connections between these iconic businessmen and explores the goods across the country. But Vanderbilt faces intense competition way they shaped the country, transforming the early on, showing that captains of industry will always be chal- U.S. into a global superpower in just 50 years. lenged by new innovators and mavericks. Tracing their roles in the oil, steel, railroad, auto and financial Key TERMS to DEFINE industries, this series uses stunning CGI and little-known stories to ARCHETYPE, ENTREPRENEUR, INFRASTRUCTURE, INGENUITY, examine the lives of these iconic tycoons. How did these leaders INNOVATION advance progress, and what were the costs and consequences of American industrial growth? What role did everyday Americans Discussion Questions play in this growth, and how were their voices heard? This series is an excellent companion for course units on business, American 1. -

Media Oligarchs Go Shopping Patrick Drahi Groupe Altice

MEDIA OLIGARCHS GO SHOPPING Patrick Drahi Groupe Altice Jeff Bezos Vincent Bolloré Amazon Groupe Bolloré Delian Peevski Bulgartabak FREEDOM OF THE PRESS WORLDWIDE IN 2016 AND MAJOR OLIGARCHS 2 Ferit Sahenk Dogus group Yildirim Demirören Jack Ma Milliyet Alibaba group Naguib Sawiris Konstantin Malofeïev Li Yanhong Orascom Marshall capital Baidu Anil et Mukesh Ambani Rupert Murdoch Reliance industries ltd Newscorp 3 Summary 7. Money’s invisible prisons 10. The hidden side of the oligarchs New media empires are emerging in Turkey, China, Russia and India, often with the blessing of the political authorities. Their owners exercise strict control over news and opinion, putting them in the service of their governments. 16. Oligarchs who came in from the cold During Russian capitalism’s crazy initial years, a select few were able to take advantage of privatization, including the privatization of news media. But only media empires that are completely loyal to the Kremlin have been able to survive since Vladimir Putin took over. 22. Can a politician be a regular media owner? In public life, how can you be both an actor and an objective observer at the same time? Obviously you cannot, not without conflicts of interest. Nonetheless, politicians who are also media owners are to be found eve- rywhere, even in leading western democracies such as Canada, Brazil and in Europe. And they seem to think that these conflicts of interests are not a problem. 28. The royal whim In the Arab world and India, royal families and industrial dynasties have created or acquired enormous media empires with the sole aim of magnifying their glory and prestige. -

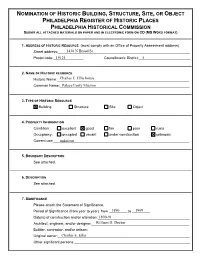

1430-N-Broad-St-Nomination.Pdf

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM ON CD (MS WORD FORMAT) 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________1430 N Broad St ________ Postal code:_______________19121 Councilmanic District:_______________5 ___________ 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________Charles E. Ellis house ________ Common Name:_________________________________________________________Palace/Unity Mission ________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Condition: excellent good fair poor ruins Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:________unknown____________________________________________________ ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See attached. 6. DESCRIPTION See attached. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1890 to _________1909 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________1890-91 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________William H. Decker _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________ _________ Original owner:_________________________________________________________Charles