Perennial Rubinstein, Late- Blooming Barlow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PCI Per Incontri Tra Le Sinistre Ri

Venerdi 28 giugno 1968 / L. 60 * Quotidiano / Anno XLV / N. 172 (-^SEt?' '!"!: . i! - • 1111 [. domenica I marines f uggono da Khe Sanh Le Sezioni sono invitate a prenotare, entro le ore 12, le copie per la diffusions di domani, sabato, festa infrasettimanale. Entro mezzo- giorno di domani dovranno poi essere com- pletate le prenotazioni per la diffusione straor- dinaria di domenica 30 giugno in occasione della pubblicazione dello speciale inserto sui problemi della liberta di stampa e di informa- zione. ORGANO DEL PARTITO COMUNISTA ITALIANO -§a WASHINGTON: brutale risposta all'appello del reverendo Abernathy VOIENZE CDNTBfl IPOVEB Approvata una nuova riduzione di 100 milioni di dollari per il programma «guerra alia poverta» Tensione nella Capitale americana - Abernathy in careere ha annunciato che digiunera per diciotto giorni - Un ragazzo negro ucciso dalla polizia a Richmond - Drammatici scontri razziali in California e North Carolina WASHINGTON, 27. II reverendo Ralph Abernathy digiunera per i di ciotto giorni che ancora deve trascorrere in carcere, alio scopo, ha detto, di risvegliare le coscienze negli Stati Uniti sulle necessita dei poveri. II dr. Abernathy, condannato a venti giorni di detenzione per una mani- SAIGON — Con grande rapidita gli americani stanno sgomberando da due giorni la base dei festazione, al termine della « marcia dei poveri» da c marines » a Khe Sanh, definita da loro imprendibile. E' it crollo di tutta I'impostaiione lui diretta, ha annunciato l'inizio del suo digiuno ad strategica americana, sulla quale era stato impegnato il prestigio di Westmoreland. I mari un gruppo di giornalisti che erano stati ammessi nella nes hanno avu'o a Khe Sanh 2500 uomini fuori comballimenlo. -

The Magazine of South Carolina

THE MAGAZINE OF SOUTH CAROLINA san One Dollar Twenty-Five JANUARY • 1971 THE GREATER GREENVILLE AREA APEX OF SOUTH CAROLINA INDUSTRY AND CULTURE ONE OF A SERIES DEPICTING UPPER SOUTH CAROLINA'S PROGRESS PROPOSED GREENVILLE DOWNTOWN COLISEUM AND CONVENTION CENTER "/"/Fr==i•E31 C:: - ,;C::,,,... "/I THE CENTER will have a seating capacity of approximately RADIO 133 13,000 for various stage shows, sporting events and GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA •MULTIMEDIA STATIONS conventions. Complementing the main area are separate exhibition and banquet facilities and a multistory ,~/Fr==iiE31 c::=: - ~ "/I parking building making this one of the most complete STEREO 937 and up to date complexes of its kind. ~7n today's world where talk comes cheap~ action speaks louder!' I When somebody wants to sell you something, you almost always know the words: We care. We understand. We're interested. We listen. We do more for you. We make it easy. It all sounds so meaningful. But by now you've realized that talk is cheap. And what's really important is the follow-through. At C&S Bank, we'll never waste words to tell you we care. Because saying it doesn't make it so. Action does. So come in. Try us. Find out about our services. Tell us what you think about the way we work for you. Write us if it's handier. We're dedicated to being the best bank in South Carolina. You say the words, we'll start the action. THE CITIZENS & SOUTHERN NATIONAL BANK OF SOUTH CAROLINA Member F.D.l.C. -

Disertační Práce

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ DIVADELNÍ FAKULTA DRAMATICKÁ UMĚNÍ Psychoplastický prostor ve scénografii Josefa Svobody Výtvarně-technická řešení inscenací Wagnerova Tristana a Isoldy DISERTAČNÍ PRÁCE Autor práce: Mgr. Martin Ondruš Vedoucí práce: doc. MgA. David Drozd, Ph.D. Brno 2019 BIBLIOGRAFICKÝ ZÁZNAM ONDRUŠ, Martin. Psychoplastický prostor ve scénografii Josefa Svobody. Výtvarně- technická řešení inscenací Wagnerova Tristana a Isoldy [Psychoplastic Space in Josef Svoboda’s Scenography. Creative and Technical Design in Productions of Wagner‘s Tristan and Isolde]. Brno, 2019, 401 s. Disertační práce. Janáčkova akademie múzic- kých umění v Brně, Divadelní fakulta, Ateliér scénografie. Vedoucí disertační práce doc. MgA. David Drozd, Ph.D. ANOTACE Disertační práce se zaobírá rekonstrukcemi výtvarně-technických řešení, které vytvo- řil významný český scénograf Josef Svoboda ke třem inscenacím hudebního dramatu Richarda Wagnera Tristan a Isolda. Tyto inscenace byly uvedeny v Hessisches Staa- tstheater Wiesbaden (1967), v Opernhaus v Kolíně nad Rýnem (1971), ve Festivalo- vém divadle v Bayreuthu (1974) a v Grand Théâtre v Ženevě (1978). Účelem práce je na základě pramenného výzkumu i studia sekundární literatury podat komplexní výklad scénografické složky těchto uvedení. V práci je prověřováno, jakým způsobem v těchto inscenacích Svoboda uplatňoval vlastní pojetí scénografie zastoupené kon- ceptem psychoplastického prostoru a jak systematicky rozvíjel inscenační postupy Laterny magiky a polyekranu založené na technologii multimédií. Podstatným hle- diskem této práce je skutečnost, že autor výše uvedených scénografií Josef Svoboda je považován za jednoho z nejvýznačnějších scénografů dvacátého století a usta- vitele oboru scénografie, jenž se výraznou měrou podílel i na jeho kritické reflexi. V teoretické části práce je proto Svobodovo pojetí scénografie nahlíženo v dějin- ném kontextu divadla od počátku dvacátého století. -

AUTOGRAPHEN-AUKTION 1. April 2017

37. AUTOGRAPHEN-AUKTION A U 1. April 2017 T O G R A P H E N - A U K T I O N 1.4. 2017 A X E L Los 386 | Johann Wolfgang von GOETHE S C Axel Schmolt | Autographen-Auktionen H Los 256 | NAPOLÉON I. u. a. M 47807 Krefeld | Steinrath 10 O Telefon (02151) 93 10 90 | Telefax (02151) 93 10 9 99 L T E-Mail: [email protected] AUTOGRAPHEN-AUKTION Hier die genaue Anschrift für Ihr Autographen-Auktionen Autographen Navigationssystem: Bücher Inhaltsverzeichnis Dokumente 47807 Krefeld | Steinrath 10 Fotos Los-Nr. Geschichte – Deutsche Länder (ohne Preußen) 1 - 19 – Preußen und Kaiserreich bis 1918 20 - 43 Krefeld A 57 – I. Weltkrieg und Deutsche Marine 44 - 53 Auktionshaus Schmolt Richtung Richtung am besten über die A 44 Abfahrt Essen – Deutsche Marine 1890-1945 54 - 57 Venlo Krefeld-Fischeln ✘ – Weimarer Republik 58 - 68 Meerbusch-Osterath – Nationalsozialismus und II. Weltkrieg 69 - 135 A 44 – Deutsche Geschichte seit 1945 136 - 199 A 44 – Britische Premierminister 18.-20. Jahrhundert 200 - 229 – Geschichte des Auslands bis 1945 230 - 263 A 61 – Geschichte des Auslands seit 1945 264 - 343 A 52 A 52 – Kirche-Religion 344 - 364 Düsseldorf Liter atur 365 - 455 Mönchengladbach Neuss Richtung A 57 Musik 456 - 633 Roermond – Oper-Operette (Sänger/-innen) 634 - 753 Bühne - Film - Tanz 754 - 978 Richtung Richtung Koblenz Köln Bildende Kunst 979 - 1177 Wissenschaft 1178 - 1223 A 57 – Forschungsreisende und Geographen 1224 - 1230 Autographen-Auktionen Axel Schmolt Luftfahrt 1231 - 1237 Steinrath 10 Weltraumfahrt 1238 - 1256 ✘ Kölner Straße A 44 Sport 1257 - 1303 Ausfahrt Osterath Widmungsexemplare - Signierte Bücher 1304 - 1316 A 44 Kreuz Meerbusch Sammlung en - Konvolute 1317 - 1345 Richtung Krefelder Straße Mönchengladbach A 57 Autographen-Auktion am Samstag, den 1. -

Franco Corelli

FRANCO CORELLI THE PERFORMANCE ANNALS 1951-1981 EDITED BY Frank Hamilton © 2003 http://FrankHamilton.org [email protected] sources Gilberto Starone’s performance annals form the core of this work; they were published in the book by Marina Boagno, Fr anco Corelli : Un Uomo, Una Voce, Azzali Editori s.n.c., Parma, 1990, and in English translation Fr anco Corelli : A Man, A Voice, Baskerville Publishers, Inc., Dallas, 1996. They hav ebeen merged with information from the following sources: Richard Swift of New York and Michigan has provided dates and corrections from his direct correspodence with the theatres and other sources: Bologna (Letter from Teatro Comunale: 5/16/86); Bussetto (see Palermo); Catania (L: Teatro Massimo Bellini: 5/26/86); Enghien-les- Bains (see Napoli); Genoa (L: L’Opera de Genoa: 5/13/86); Hamburg (L: Hamburgische Staatsoper: 5/15/86); Lausanne (L: Theatre Municipal, Lausanne: 5/12/86); Lisbon (L: Teatro Nacional São Carlos: 1986); Livorno (L: Comune di Livorno: 5/31/87); Madrid (L: Teatro Nacional de La Zarzuela: 1/26/87); Modena (L: Comune di Modena: 10/16/87); Napoli (Il Mondo Lirico); Nice (L: Opera de Nice: 5/2/86, 8/5/88); Palermo (L: Teatro Massimo: 6/10/86, 10/13/88); Piacenza (L: Comune di Piacenza u. o. Teatro Municipale: 6/10/86); Rome (Opera Magazine); Rovigo (L: Accademia dei Concordi, Rovigo: 11/11/86, 2/12/87); San Remo (L: Comune di San Remo: 11/8/86); Seattle (Opera News 11/1967); Trieste (L: Teatro Comunale: 4/30/86). The following reference books are listed alphabetically by venue. -

Regional Oral History Office the Bancroft Library University Of

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California S6ndor Salgo TEACHING MUSIC AT STANFORD, 1949-1974, DIRECTING THE CARMEL BACH FESTIVAL AND THE MARIN SYMPHONY, 1956-1991 With an Introduction by Robert P. Commanday Interviews Conducted by Caroline C. Crawford in 1994-1996 Copyright 0 1999 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by legal agreements between The Regents of the University of California and SQndor Salgo and Patricia Salgo dated October 26, 1995, and February 15, 1996, respectively. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. -

Kafkas Schimpans Nder 1997 Kom Jag För Första Gången I Kontakt Med John Metcalfs Och Mark Morris Kammaropera ”Kafka’S Chimp” Som Den Heter På Originalspråk

Kafkas schimpans nder 1997 kom jag för första gången i kontakt med John Metcalfs och Mark Morris kammaropera ”Kafka’s Chimp” som den heter på originalspråk. UJag fascinerades av musiken, handlingen, budskapet och av det sätt som verket bryter mot konventionell operatradition, inte för brytandets skull utan för att söka finna nya vägar för nutida musikteater. Här är en opera som inte bygger på personliga konflikter utan snarare konflikter inom varje person. Här finns ingen hierarki; stycket görs utan dirigent, och musiker, sångare och dansare agerar på scenen samtidigt. Man kliver över osynliga gränser, in på varandras områden och resultatet blir ett märkligt kammarspel där alla lever och är beroende av var- andra. Verket kan sägas vara en romantisk komedi, något som inte alltför ofta förekommer inom nutida kammaropera eller nutida opera över huvud taget. Jag bjuder er mycket nöje med Kafkas Schimpans – och när ni kommer hem i kväll och tittar er i spegeln... Kjell Englund Konstnärlig ledare KAFKAS SCHIMPANS 1 Historiker säger oss att 1900-talet har varit unikt som den långa period då vår scenrepertoar dominerats av tidigare tiders och tidigare kulturers musik. För tio år sedan var vårt något ironiska motto: ”Spela lite 1900-talsmusik innan seklet är slut” och under de senaste tio åren har den nya opera/musikteaterfor- men rest sig som en fågel Fenix – även om man måste medge att den fortfarande är skygg och trevande. Internationellt är skapandet och produce- randet av nya operor och särskilt nya kammaroperor på remarkabel uppgång. Som väntat efter en så lång period av för- summelse är såväl skapare och uttolkare som publik otränade. -

ROUTES, a Guide to Black Entertainment November 1977 As

And no wonder. To their amaze scope to please everybody. Even a form in this issue and ROUTES ment, it does tell you what to do section to help you decide just will be on its way sooner than you and where to go. It is an easy where to take your kids. So don't think. Also, ROUTES will make an reference and it's good reading too. tarry! Find out what's going on by excellent Christmas gift. It's a con Sports, music, dining, theatre, and subscribing to ROUTES today. venient and easy way to shop. museums of special interests are And you'll have something to talk Routes listings that provide insight and about too. Fill out the subscription Box 767 Flushing,New York,l1352 Pub isher SStatement s I sat in transit from Lan ity to recognize talent and availing caster, Pennsylvania, re themselves of the offerings. Others, Aturning with copies of our through envy and dismay knock first issue, I reflected on several oc each other and as a result some ideas casions-some apparent and some never bloom. unwarranted. As a new publisher, Hence, we are about being better trying to achieve credibility can be people and helping each other hard. To friends, associates and achieve and survive. There is a need others who can share their expertise for ROUTES and we intend to fill in assisting you, your idea seems the void. Our hope is that in doing senseless and should be abandoned. our best, we help others get ahead as As I look over my shoulder at the well. -

Teachingmusic00salgrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Sandor Salgo TEACHING MUSIC AT STANFORD, 1949-1974, DIRECTING THE CARMEL BACH FESTIVAL AND THE MARIN SYMPHONY, 1956-1991 With an Introduction by Robert P. Commanday Interviews Conducted by Caroline C. Crawford in 1994-1996 Copyright 1999 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by legal agreements between The Regents of the University of California and Sandor Salgo and Priscilla Salgo dated October 26, 1995, and February 15, 1996, respectively. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. -

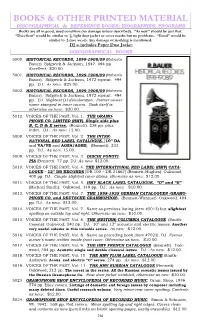

Books & Other Printed Material

BOOKS & OTHER PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS; BIOGRAPHIES; PROGRAMS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). “As new” should be just that. “Excellent” would be similar to 2, light dust jacket or cover marks but no problems. “Good” would be similar to 3 (use wear). Any damage or marking is mentioned. DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket DISCOGRAPHICAL BOOKS 5000. HISTORICAL RECORDS, 1899-1908/09 (Roberto Bauer). Sidgwick & Jackson, 1947. 494 pp. Excellent. $20.00. 5001. HISTORICAL RECORDS, 1899-1908/09 (Roberto Bauer). Sidgwick & Jackson, 1972 reprint. 494 pp. DJ. As new. $25.00. 5002. HISTORICAL RECORDS, 1899-1908/09 (Roberto Bauer). Sidgwick & Jackson, 1972 reprint. 494 pp. DJ. Slightest DJ discoloration. Former owner name stamped in inner covers. Book itself is otherwise as new. $20.00. 5012. VOICES OF THE PAST, Vol. 1. THE GRAMO- PHONE CO. LIMITED (HMV). Single side plus B, C, D & E series. (Bennett). 238 pp. plus index. DJ. As new. 12.00. 5008. VOICES OF THE PAST, Vol. 2. THE INTER- NATIONAL RED LABEL CATALOGUE. [10” DA and VA/VB and AGSA/AGSB]. (Bennett). 233 pp. DJ. As new. 15.00. 5009. VOICES OF THE PAST, Vol. 3. DISCHI FONOTI- PIA (Bennett). 77 pp. DJ. As new. $12.00. 5010. VOICES OF THE PAST, Vol. 4. THE INTERNATIONAL RED LABEL (HMV) CATA- LOGUE – 12” DB RECORDS [DB 100 – DB 21667] (Bennett-Hughes). Oakwood. 400 pp. DJ. Couple slightest cover stains, otherwise as new. $12.00. 5011. VOICES OF THE PAST, Vol. 5. HMV BLACK LABEL CATALOGUE. “D” and “E” (Michael Smith). -

L'œuvre À L'affiche

L'œuvre à l'affiche Recherches: Jean-Louis Dutronc, Elisabetta Soldini avec la contribution de César Arturo Dillon et Georges Farret Calendrier des premières représentations de Boris Godounov d’après A. Loewenberg, Annals of Opera 1597-1940, Londres 1978. Le signe [▼] renvoie aux tableaux des pages suivantes. Sauf indication contraire, signalée par une abréviation entre parenthèses, l’œuvre a été donnée en russe : [A] allemand, [An] anglais, [B] bulgare, [C] croate, [D] danois, [Es] estonien, [F] finnois, [Fl] flamand, [Fr] français, [H] hongrois, [I] italien, [L] letton, [Li] lituanien, [P] polonais, [R] roumain, [Sl] slovène, [Su] suédois, [Tc] tchèque. Voir aussi dans ce volume les dates des avant-premières de Boris (pages 10-11) et l’article de J.-M. Jacono. 1874 : 27 janvier, création au Théâtre Marie de Saint-Pétersbourg (version origi- nale, 1872). Avec, notamment, Ivan A. Melnikov (Boris), Fyodor Kommissarjewski (Dimitri), Julia Platonova (Marina), Vladimir Vasilyev (Pimène), Vasily Vasilyev Ossip Petrov (Varlaam) et Sobolew (Missaïl). Direction : Eduard Napravnik. 1888 : 28 décembre, Moscou, Théâtre Bolchoï. 1896 : 10 décembre, Saint-Pétersbourg, Conservatoire, (version Rimski- Korsakov). 1908 : 19 mai, Paris, Opéra.[▼] 1909 : 14 janvier, Milan, Teatro alla Scala, version de Michel Delines et Ernesto Palermi. [I] [▼] - 13 septembre : Buenos Aires, Teatro Colon, version de Michel Delines et Ernesto Palermi. Avec notamment Eugenio Giraldoni dans le rôle titre. Direction : Luigi Mancinelli.. [I] 1910 : 18 juin, Rio de Janeiro, version de Michel Delines et Ernesto Palermi [I] - 25 novembre, Prague, version de Rudolf Zamrzla. [Tc] 1911 : 5 novembre, Stockholm, version de Sven Nyblom. [Su] 1912 : 23 janvier, Monte-Carlo. - Lemberg. [P] 1913 : 28 janvier, Lyon, version de Michel Delines et Louis Laloy. -

Catalogue 2018

CATALOGUE 2018 Cast The Arthaus Musik classical music catalogue features more than 400 productions from the beginning of the 1990s until today. Outstanding conductors, such as Claudio Abbado, Lorin Maazel, Giuseppe Sinopoli and Sir Georg Solti, as well as world-famous singers like Placido Domingo, Brigitte Fassbaender, Marylin Horne, Eva Marton, Luciano Pavarotti, Cheryl Studer and Dame Joan Sutherland put their stamp on this voluminous catalogue. The productions were recorded at the world’s most renowned opera houses, among them Wiener Staatsoper, San Francisco Opera House, Teatro alla Scala, the Salzburg Festival and the Glyndebourne Festival. Unitel and Arthaus Musik are proud to announce a new partnership according to which the prestigious Arthaus Musik catalogue will now be distributed by Unitel, hence also by Unitel’s distribution partner C Major Entertainment. World Sales: All rights reserved · credits not contractual · Different territories · Photos: © Arthaus · Flyer: luebbeke.com Tel. +49.30.30306464 [email protected] Unitel GmbH & Co. KG, Germany · Tel. +49.89.673469-630 · [email protected] www.unitel.de OPERA ................................................................................................................................. 3 OPERETTA ......................................................................................................................... 35 BALLET ............................................................................................................................... 36 CONCERT...........................................................................................................................