Picking up the Pieces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

URBICIDE II 2017 @ IFI IRAQ PALESTINE SYRIA YEMEN Auditorium Postwar Reconstruction AUB

April 6-8 URBICIDE II 2017 @ IFI IRAQ PALESTINE SYRIA YEMEN Auditorium Postwar Reconstruction AUB Thursday, April 6, 2017 9:30-10:00 Registration 10:00-10:30 Welcome and Opening Remarks Abdulrahim Abu-Husayn (Director of the Center for Arts and Humanities, AUB) Nadia El Cheikh (Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, AUB) Halit Eren (Director of IRCICA) 10:30-11:00 Keynote Presentation Heritage Destruction: What can be done in Prevention, Response and Restoration (Francesco Bandarin, UNESCO Assistant Director General for Culture) 11:00-11:15 Coffee Break 11:15-12:45 Urbicide Defined Session Chair: Timothy P. Harrison Background and Overview of Urbicide II (Salma Samar Damluji, AUB) Reconstructing Urbicide (Wendy Pullan, University of Cambridge) Venice Charter on Reconstruction (Wesam Asali, University of Cambridge) 12:45-14:00 Lunch Break 14:00-15:45 Memory, Resilience, and Healing Session Chair: Jad Tabet London – Resilient City (Peter Murray, New London Architecture and London Society) IRCICA’s Experience Rehabilitating Historical Cities: Mostar, al-Quds/Jerusalem, and Aleppo (Amir Pasic, IRCICA, Istanbul) Traumascapes, Memory and Healing: What Urban Designers can do to Heal the Wounds (Samir Mahmood, LAU, Byblos) 15:45-16:00 Coffee Break 16:00-18:00 Lebanon Session Chair: Hermann Genz Post-Conflict Archaeological Heritage Management in Beirut (1993-2017) (Hans Curvers, Independent Scholar) Heritage in Post-Conflict Reconstruction: Assessing the Beirut Experience (Jad Tabet, UNESCO World Heritage Committee) Climate Responsive Design -

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq As a Violation Of

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq as a Violation of Human Rights Submission for the United Nations Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights About us RASHID International e.V. is a worldwide network of archaeologists, cultural heritage experts and professionals dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the cultural heritage of Iraq. We are committed to de eloping the histor! and archaeology of ancient "esopotamian cultures, for we belie e that knowledge of the past is ke! to understanding the present and to building a prosperous future. "uch of Iraq#s heritage is in danger of being lost fore er. "ilitant groups are ra$ing mosques and churches, smashing artifacts, bulldozing archaeological sites and illegall! trafficking antiquities at a rate rarel! seen in histor!. Iraqi cultural heritage is suffering grie ous and in man! cases irre ersible harm. To pre ent this from happening, we collect and share information, research and expert knowledge, work to raise public awareness and both de elop and execute strategies to protect heritage sites and other cultural propert! through international cooperation, advocac! and technical assistance. R&SHID International e.). Postfach ++, Institute for &ncient Near -astern &rcheology Ludwig-Maximilians/Uni ersit! of "unich 0eschwister-Scholl/*lat$ + (/,1234 "unich 0erman! https566www.rashid-international.org [email protected] Copyright This document is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution .! International license. 8ou are free to copy and redistribute the material in an! medium or format, remix, transform, and build upon the material for an! purpose, e en commerciall!. R&SHI( International e.). cannot re oke these freedoms as long as !ou follow the license terms. -

Protecting Cultural Property in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Syria and Iraq

Protecting Cultural Property in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Syria and Iraq Louise Arimatsu and Mohbuba Choudhury 91 INT’L L. STUD. 641 (2015) Volume 91 2015 Published by the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law International Law Studies 2015 Protecting Cultural Property in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Syria and Iraq Louise Arimatsu and Mohbuba Choudhury CONTENTS I. Introduction ................................................................................................ 641 II. Why We Protect Cultural Property .......................................................... 646 III. The Outbreak of the Current Armed Conflicts and the Fate of Cultural Property ....................................................................................................... 655 A. Syria ....................................................................................................... 656 B. Iraq ......................................................................................................... 666 IV. The Legal Landscape in Context ............................................................. 670 A. Obligations on the Parties to the Conflict ....................................... 671 B. Consequences of a Failure to Comply with Obligations ............... 685 V. Concluding Comments .............................................................................. 695 I. INTRODUCTION O n June 24, 2014, a month after ISIS1 leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi de- clared the formation of an Islamic Caliphate stretching from northern -

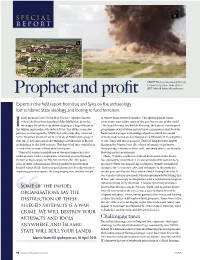

Prophet and Profit Left Nimrud, Before the Explosions

special report ABOVE The Assyrian palace at Nimrud is blown up by Islamic State militants. Prophet and profit LEFT Nimrud, before the explosions. Experts in the field report from Iraq and Syria on the archaeology lost to Islamic State ideology, and looting to fund terrorism. n her memoir Come Tell Me How You Live, Agatha Christie, of tribute from defeated enemies. Though finds from earlier wife of the British archaeologist Max Mallowan, describes excavations now adorn some of the great museums of the world the happy life of the expedition digging at Chagar Bazaar in – the Iraq Museum, the British Museum, the Louvre – an inspired Ithe Jezirah region of north-eastern Syria. The idyllic scene she programme of excavation and restoration in more recent decades paints was interrupted by WWII, but afterwards they returned had created a unique archaeological park in which one could to the Near East and went on to excavate at Nimrud in a project actually walk round an Assyrian palace with many of its sculptures that was to become one of the defining contributions of British in situ. Tragically this is no more. The building has been largely archaeology in the 20th century. How horrified they would be to destroyed by Islamic State (IS), whose infamous video shows see what has become of that wonderful place. them prising sculptures off the wall, smashing others, and finally Nimrud is unquestionably one of the most important sites blowing up this monument. of the ancient world, a capital city of ancient Assyria through Hatra, 70 miles southwest of Mosul and a jewel in the desert, its time of high empire in 9th-7th centuries BC. -

Report on the Situation of Cultural Heritage in Iraq up to 30 May 20031

Report on the situation of cultural heritage in Iraq up to 30 May 20031 BACKGROUND In line with its constitutional mandate in the field of cultural heritage and following diplomatic actions in order to alert the coalition authorities to the damages to the cultural heritage of Iraq as a result from the conflict, the Director-General convened at UNESCO Headquarters the first meeting of high-level international experts on the cultural heritage of Iraq (17 April 2003) to respond to the alarming situation affecting the cultural heritage of Iraq as a result from the conflict. The meeting had the following 3 objectives: (i) to coordinate the international scientific network of experts on Iraqi cultural heritage; (ii) to formulate guidelines for a consolidated strategy in the field of post-conflict intervention and rehabilitation of the cultural heritage of Iraq; (iii) to devise an emergency safeguarding plan. Following the recommendations of the above-mentioned meeting, a second meeting organized upon the initiative of the British Museum in London (29 April 2003), focusing on the situation of the Iraqi National Museum in particular and the need to restore inventories. Upon the approval of Office for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (ORHA) and in close collaboration with the US Observer Mission to UNESCO, the Director-General called for the organization of an urgent expert mission to assess the extent of damage and loss to cultural property in Iraq and elaborate a first report on the state of Iraqi cultural heritage. The UNESCO experts’ mission visited Baghdad, from 17 to 20 May 2003. PARTICIPANTS The first UNESCO mission to Iraq was led by Mr Mounir Bouchenaki, Assistant Director- General for Culture of UNESCO. -

The Cultural Heritage of Iraq After the 2Nd Gulf War (1)

The Cultural Heritage of Iraq after the 2nd Gulf War (1) John Curtis (*) Abstract: * British Museum Keeper Curator This paper conducts a review of the situation in which currently Iraq’s archaeological heritage finds itself, following Department Middle East the military intervention carried out by United States and its allies in Iraq, which has had a tremendous impact not [email protected] only on archaeological sites but also on cultural centers and museums Institutions in Baghdad and Mosul. Resumen: En este trabajo se lleva a cabo una revisión de la situación en la que se encuentra actualmente el patrimonio arqueo- lógico iraquí tras la intervención militar llevada a cabo por Estados Unidos y sus aliados en Iraq, que ha afectado de manera importante no sólo a sus yacimientos arqueológicos sino también a los centros culturales y a las instituciones museísticas de Bagdad y Mosul. 75 MARQ. ARQUEOLOGÍA INTRODUCCIÓN Mesopotamia, modern Iraq, has often, quite rightly, been called the cradle of civilization. Here, from about 8000 BC onwards, in the rich alluvial plain created by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, we find evidence for settled communities that are dependent on farming rather than hunting and gathering. After 3000 BC we see the formation of the first cities, the introduction of complex economies, and the invention of writing. In the south part of Mesopotamia, Sumerian civilization flourished in the 3rd millennium BC at cities such as Warka and Ur. In the 2nd millennium BC, the Sumerians were replaced in central Mesopotamia by the Babylonians, whose capital was at Babylon and whose best-known king was Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC), famous for his law code. -

Interview with Dia Al Azzawi 4/11/17, 11:06 AM

» Interview with Dia Al Azzawi 4/11/17, 11:06 AM (http://artbahrain.org/home) BREAKING ! Salon Suisse: ATARAXIA (http://artbahrain.org/home/?p=10356) Home (http://artbahrain.org/home)FRENCH PAVILION: Xavier Veilhan (http://artbahrain.org/home/?p=10380) ∠ Damien Hirst: TREASURES FROM THE WRECK OF THE UNBELIEVABLE (http://artbahrain.org/home/?p=10376) interview (http://artbahrain.org/home/?cat=14) Loris Gréaud: The Unplayed Notes Factory (http://artbahrain.org/home/?p=10371) Ahmed Morsi: A Dialogic Imagination (http://artbahrain.org/home/?p=10366) Diaspora Pavilion (http://artbahrain.org/home/?p=10361) Interview with Dia Al Azzawi # artBahrain (http://artbahrain.org/home/?author=1) $ September 29, 2016 % interview (http://artbahrain.org/home/?cat=14) http://artbahrain.org/home/?p=9113 Page 1 of 28 » Interview with Dia Al Azzawi 4/11/17, 11:06 AM An Excavation of the Hidden Protest By Valerie Didier Hess The title of this very much-anticipated retro- spective show of your entire oeuvre taking place both at Mathaf and Al Riwaq Gallery in Doha, ‘I‘I amam thethe cry,cry, whowho willwill givegive voicevoice toto me’ refers to the title of a poem by Fadhil Al- Azzawi. Why was this particular title cho- sen? I understand that this phrase was sup- posed to be the title of your last exhibition in Baghdad in 1975, but it was changed to ‘Human States’ (‘Halaat‘Halaat Insaniyya’Insaniyya’)? Fadhil was and is one of the modernist poets of my generation. He was both a novelist and jour- nalist at the same time, and politically, he was a leftist. -

Gordion Newsletter 2011

October 2019 Iraqi Institute students learning methods for safely lifting damaged stone sculptures for conservation. The heritage of ancient Mesopotamia, city of Babylon, 19th-century Ottoman old Assyrian ruins that stood just outside the “cradle of Western civilization,” is homes, and historic souks document the ISIS-occupied Mosul. The demolition vitally important to the people of Iraq. complex web of faiths, empires and trade came amidst a wave of ISIS vandalism Iconic sites throughout the country, that have shaped Iraq. against ancient sites in northern Iraq. including the famed temples of Babylon, In recent times, this history has Even before the ISIS campaign the ziggurat at Ur, and the palace at suffered greatly. On April 11, 2015, the to destroy cultural heritage, historical Nimrud, capital of the Assyrian empire, Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) sites suffered from decades of neglect, chronicle early human history and the released a video of the ancient city of violence, and instability that have further roots of western civilizations. Religious Nimrud erupting in a colossal cloud of compromised conservation efforts. In one and secular structures such as the spiral dust. After attacking ancient sculptures of the most notorious examples, looters minaret at Samarra, the Yazidi temple with sledgehammers and power tools, the took thousands of objects from the Iraq at Lalesh, the Erbil citadel, the ancient terrorist group detonated the 3,000-year- National Museum in the early days of the 1 U.S. invasion of Baghdad in 2003. community’s sense of identity and Delaware, the Smithsonian Institution, These besieged Iraqi sites and cohesion as well as destroy livelihoods. -

THIS ISSUE: IRAQ – People and Heritage the Rise and Fall Of

Volume 11 - Number 4 June – July 2015 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: IIRAQRAQ – PeoplePeople andand HeritageHeritage ● TThehe rriseise aandnd ffallall ofof tthehe nnationation ● TThehe KKurdsurds aandnd ISISISIS ● TThehe YYezidisezidis ofof SinjarSinjar ● TThehe aartificertifice ofof tthehe destructiondestruction ofof aartrt iinn IIraqraq ● OObliteratingbliterating Iraq’sIraq’s ChristianChristian heritageheritage ● NNimrudimrud reducedreduced toto rubblerubble ● IInterviewnterview wwithith SSaadaad al-Jadiral-Jadir ● SSupportingupporting humanitieshumanities andand cultureculture forfor a sustainablesustainable IraqIraq ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eventsevents iinn LondonLondon Volume 11 - Number 4 June – July 2015 £4 TTHISHIS IISSUESSUE: IIRAQRAQ – PeoplePeople andand HHeritageeritage ● TThehe rriseise aandnd ffallall ofof tthehe nnationation ● TThehe KKurdsurds aandnd IISISSIS ● TThehe YYezidisezidis ooff SSinjarinjar ● TThehe aartificertifice ooff tthehe ddestructionestruction ofof aartrt iinn IIraqraq ● OObliteratingbliterating Iraq’sIraq’s CChristianhristian heritageheritage ● NNimrudimrud rreducededuced ttoo rrubbleubble ● IInterviewnterview wwithith SSaadaad aal-Jadirl-Jadir ● SSupportingupporting hhumanitiesumanities aandnd cultureculture fforor a ssustainableustainable IIraqraq ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents iinn LLondonondon Athier, Man Of War VIII. 175 X 190. Acrylic on canvas Courtesy of Ayyam Gallery About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) © Athier Th e London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the -

(CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-IZ-100-17-CA021 December 2017 Monthly Report Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, William Raynolds, Allison Cuneo, Kyra Kaercher, Darren Ashby, Gwendolyn Kristy, Jamie O’Connell, Nour Halabi Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 9 Incident Reports: Iraq 100 Incident Reports: Libya 131 Satellite Imagery and Geospatial Analysis 150 Heritage Timeline 155 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points Syria ● Aleppo Governorate ○ A reported SARG or Russian airstrike damages the Jub Abyad Mosque in Jub Abyad, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0225 ○ Reported Russian airstrikes damage Tal al-Daman Mosque in Tal al-Daman, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0227 ● Daraa Governorate ○ Future Horizons and Hello Trust clean up debris at Bosra al-Sham in Bosra al-Sham, Daraa Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0230 ● Deir ez-Zor ○ A reported SARG airstrike damages the Fatima al-Zahra Mosque in al-Bukamal, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0222 ○ Reported SARG shelling damages al-Hashish Mosque in al-Sha’fa, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 17-0223 ○ DigitalGlobe satellite imagery reveals damage to exposed architecture at Mari, Tell Hariri, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

Assessment of Damage to Libraries and Archives in Iraq

ASSESSMENT OF DAMAGE TO LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES IN IRAQ 1. Update based on: • Verbal report by Dr Donny George, Director of Research, Iraqi Museum, to the meeting convened by the British Museum and UNESCO 29th April 2003 to discuss International Support for Iraq’s Museums • Written report by Edouard Méténier, a French researcher who spent 6 months working in Iraqi libraries, mostly in Baghdad from November 2002 until early April (Aperçu sur l’état des bibliothèques et dépôts d’archives irakiens au terme de la guerre d’avril 2003) • Information posted on various web-groups (H-ISLAM, H-LEVANT, etc.) • Best source of information on Iraq's manuscript libraries - their collections and the bibliography of those collections - is G. Roper ed. World survey of Islamic manuscripts Vol. 2 (London, 1993). 2. Libraries in Baghdad: • Library of the Iraqi Museum: one of the finest collections on history and archaeology of the Middle East – most evacuated before the war started – completely protected • Islamic Manuscripts Collection of the Iraqi Museum: about 4,000 volumes - likewise evacuated before the war to a bunker away from the main museum building – all safe (i.e. not transferred to the Saddam Manuscripts House in 1988 as reported in Roper's Survey) • National Library of Iraq: about 500K printed books and serials (including 5K rare books) – looted and burnt (suffered from its location opposite the Iraqi Defence Ministry building) - but some holdings at least (e.g. early newspapers) reported to have been evacuated beforehand and to be safe • National Archives of Iraq (which shared the same building as the National Library): containing documents from the Ottoman period onwards - size of contents unknown (no published catalogue traced) – likewise looted and burnt, but again some material at least (e.g. -

Learning from the Iraq Museum

AJA OPEN ACCESS: MUSEUM REVIEW www.ajaonline.org Learning from the Iraq Museum Donny George Youkhanna* INTRODUCTION ning of its history. This entirely documented The Iraq Museum was founded in 1923 collection of finds from the cradle of civilization when Gertrude Bell, the British woman who encapsulates the most essential cornerstones of helped establish the nation of Iraq, stopped our modern life, including agriculture, writ- the archaeologist Leonard Woolley from tak- ing, laws, mathematics, astronomy, the arts, ing out of the country all of his extraordinary and warfare. third-millennium B.C.E. finds from the ancient Sumerian city of Ur (esp. the jewelry of the THE MUSEUM UNDER ATTACK royal cemetery)1 for division between the Brit- The protection of a museum’s holdings in ish Museum in London and the University of times of warfare or civil unrest is a multifaceted Pennsylvania’s Museum in Philadelphia. She and complicated issue. Because museums pres- believed that the Iraqi people should have a ent themselves as—and are routinely portrayed share of this archaeological discovery made in by the media as—storehouses and display ven- their homeland and, thereby, started a museum ues of treasure, they become targets of looting in central Baghdad, pressing into service two by organized gangs and by people from the rooms in an Ottoman barracks as its very first street. Because invading armies see all armed galleries. Material from ongoing excavations personnel as potential enemies, guards at mu- continued coming into this young museum, seums and other cultural institutions tend to and in 1936, it moved to another building be attacked or to slip away as fighting nears.